A new investigation shows that farms located in the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Territory in the Brazilian Amazon supplied two JBS meatpacking plants that sell beef to brands of the French supermarket giant.

“We were walking along the road and all of a sudden, some people started coming out of the bush and appearing in cars and motorcycles. They surrounded us and said we were on private property. I told them it was Indigenous land, and they knew it.” That is how Indigenous peoples’ rights advocate Ivaneide Bandeira described the moments of tension she faced together with some Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau on Mother’s Day, Sunday, May 14.

“This is not going to be as easy as you think, make no mistake about it,” said one of the men who surrounded Neidinha, as the environmentalist and founder of the Kanindé Ethno-Environmental Association is known. She filmed the encounter.

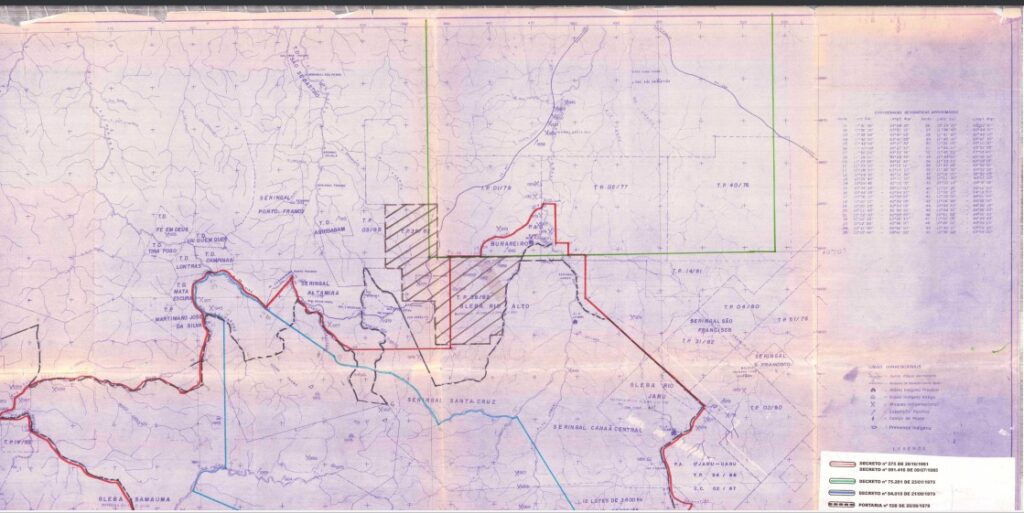

The confrontation took place in an area of Rondônia’s Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Land known as Burareiro — a Brazilian Amazon region where encroachers have cattle ranches that supply large meatpacking companies and supermarket chains.

In March 2021, a lawsuit was filed in France against French group Casino Guichard-Perrachon, which controls supermarket chains Pão de Açúcar, Assaí and Extra Hiper, for selling meat from suppliers directly linked to illegal deforestation in the Amazon, including farms located in the Burareiro area.

The case falls under the 2017 so-called Vigilance Law, according to which large corporations based in Brazil must ensure that “both their subsidiaries and their subcontracted companies” do not cause “severe violations of human rights and fundamental liberties or harms to people’s health and safety, and the environment.”

While Casino claimed in the French court that it has a strict system of control over its supply chain, its stores in Brazil keep selling meat from cattle raised in protected areas.

That is described in a new investigation by the InfoAmazonia Geojournalism Laboratory conducted in partnership with the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA). They examined more than 500,000 records of cattle transportation in the area of influence of two JBS meatpacking plants that supply meat to Casino, covering 2018-22.

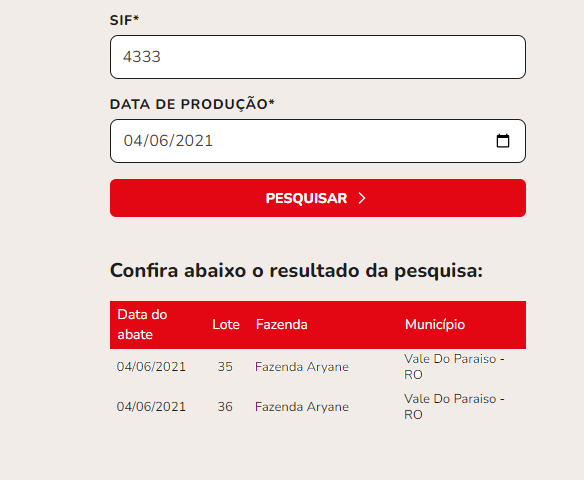

Data from documents known as Animal Transit Registrations (GTAs) indicate that JBS’ slaughter plants in Pimenta Bueno (registered at the Federal Inspection Service/SIF under number 2880) and Vilhena (SIF 4333), both in Rondônia state, received animals from the Indigenous land and other protected areas after March 2021, when Indigenous peoples from Brazil and Colombia, with support from international NGOs, filed a lawsuit against Casino in France.

Using data from suppliers who delivered cattle directly to these two meatpackers, InfoAmazonia and CCCA examined the supply chain backward and, based on the information from GTAs, found producers operating within the Indigenous land.

In most cattle transactions analyzed, animals were not transferred directly from farms located in the Indigenous land to JBS. However, after they transited through different farms and arrived at meatpacking plants, it was no longer possible to tell the difference between those that came from the Indigenous land and others. This maneuver is known as cattle laundering and aims to hide any potentially illegal origin of the animals.

One of the suppliers who would have resorted to that practice is Orlando Alves Trindade, whose Coimbra farm covers more than 1,000 hectares (2,470 acres) of land overlapping the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Land (UEWW IL).

Trindade transferred cattle from the Coimbra farm to another of its properties outside the Indigenous Land — the Aryane farm — which supplied the JBS meatpacking plant in Vilhena.

According to information obtained by the investigation on May 15, 2021, two months after the lawsuit was filed against Casino in France, JBS’ Vilhena unit received 54 animals from the Aryane farm. The traceability section on the company’s website, where the origin of products can be consulted, says that animals coming from that farm were slaughtered June 4.

But what the data provided by JBS do not show is that, two months earlier, the Aryane farm had received 90 head of cattle from the Coimbra farm, located inside the Indigenous land.

Questioned by InfoAmazonia, JBS stated that it “cannot monitor the other links of its supply chain” and therefore cannot guarantee control over the entire supply chain since its origin. (See JBS statement below.)

In 2021, a report by Brazil’s National Council of Justice (CNJ) mentioned the need for conducting inspections at the Coimbra farm and proposed the installation of barriers in the area to prevent land invasions. The farm is just 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) from the Jamari Indigenous village, located within the UEWW IL. The CNJ also recommended canceling all registrations of rural properties within the Indigenous Land as a way of curbing exploitation in these areas.

There is no information about inspections being conducted on that farm. However, in 2022, Rondônia’s Legislative Assembly declared Trindade an honorary citizen “for his services to the state.”

From 2019-21, the Coimbra farm provided 179 head of cattle to several farms that supply JBS, according to transport registration data (GTAs). The areas within the Indigenous land were purchased by Trindade between 2001 and 2002, more than two decades after the government demarcated the territory, which was officially established in 1991.

In an area adjacent to the Coimbra farm, inside the Indigenous land, we found another indirect supplier of JBS. The Dois Irmãos farm transferred more than 100 animals to properties that traded cattle with JBS’ slaughter unit in Pimenta Bueno.

Both farms have had their Rural Environmental Registrations (CAR) canceled by court decisions since 2017, but the occupants were never removed from the area — on the contrary, according to data from the GTAs analyzed, these properties continue their livestock activity within the Indigenous land, vaccinating the animals and moving them around in different properties to bypass the supply chain’s monitoring systems.

Similarly to the Coimbra and Dois Irmãos farms, our investigation found that at least 15 farms overlapping the Indigenous land sold cattle to Casino’s suppliers in Rondônia after March 2021. Between 2018 and 2022, 46 properties were identified within the Indigenous land, which would have managed 8,000 head of cattle.

Ranches in IT fed JBS’s direct suppliers

In Casino’s supermarkets in Brazil, InfoAmazonia also found meat with SIF codes corresponding to meatpackers related to UEWW IL invasion. The most recent case took place at an Assaí store in Rio de Janeiro’s Tijuca district in May 2023. Meat from these suppliers was also found in Piracicaba, São Paulo. In September 2022, the organization Mighty Earth also found meat from the same sources in an Assaí store in the city of São Paulo.

State and federal health agencies have the same data analyzed by InfoAmazonia and CCCA. However, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock considers it sanitary and public health information strategic for trade agreements and therefore is not willing to share data from GTAs with environmental agencies.

In May, the Ministry of the Environment (MMA) said it plans to integrate information from GTAs with other public databases to increase control over deforestation in the Amazon.

The investigation also found that the supply chains of Pão de Açúcar, Assaí and Extra supermarkets received cattle that could have come from the Sete de Setembro and Igarapé Lage Indigenous lands and several conservation units, including the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve, the Rio Preto-Jacundá Extractive Forest and the Guajará-Mirim State Park, all in Rondônia.

Burareiro, a powder keg

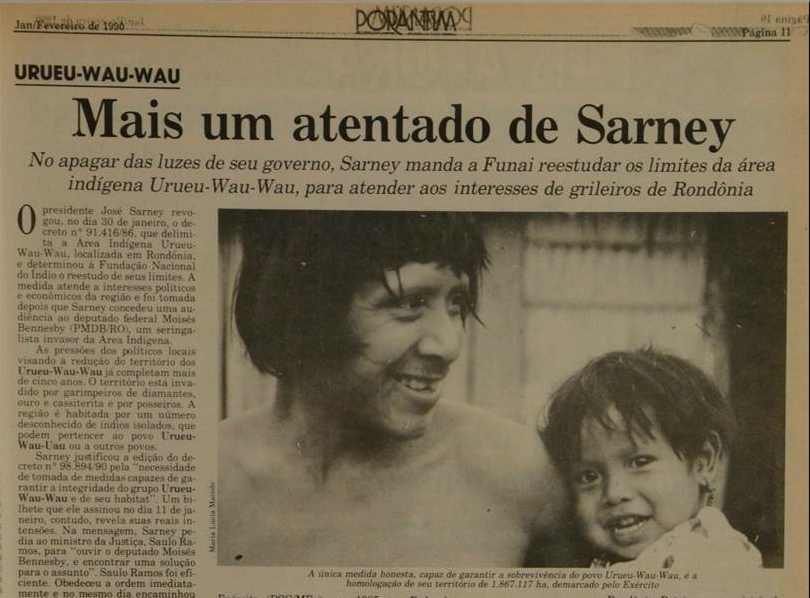

The approximately 15,000 ha (37,000 acres) of the Indigenous land that became the epicenter of the conflict between ranchers and Indigenous people — and where most invasions of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau territory start — originate from the territorial expansion project created by the military dictatorship for the Amazon, which settled 115 families in the Indigenous territory in the 1970s.

The Brazilian state’s historical failure to solve the situation has resulted in more occupation of that area by encroachers, who have joined new deforestation fronts in recent years.

The Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Territory is among the most deforested Indigenous lands in the Amazon, according to data from the National Institute for Space Research. The peak of deforestation occurred in 2019, when 49,000 ha (121,000 acres) of forest were destroyed. According to MapBiomas, pastures in that Indigenous land reached 34,000 hectares (84,000 acres) in 2021 — three times the size of Paris. And most of that devastation was concentrated in the Burareiro area.

Deforestation in the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau IT

Cattle farms are able to operate because properties overlapping Indigenous lands can be registered on the Rural Environmental Registration (CAR), which is self-declaratory and aims to gather environmental information on rural properties and possessions. While registrations must be validated for effective environmental control, it is possible to raise cattle with the number alone.

“The CAR has become some sort of parallel notary office, which is supposed to certify compliance with environmental legislation without verifying it,” said environmentalist and Indigenous peoples expert Márcio Santilli in an interview with InfoAmazonia. Santilli is a former president of the Brazilian Indigenous affairs agency Funai (1995-96) and the founder of Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), a nonprofit that advocates for the rights of Indigenous and traditional peoples. He said the mechanism has been systematically sabotaged by lawmakers connected to landowners who have been postponing the deadlines for its full implementation.

The investigation found 563 environmental registrations of land located in that Indigenous territory since 2012, when CAR was created.

In 2020, the Federal Prosecution Service filed a public civil lawsuit demanding the suspension of animal transit registrations (GTA) related to CARs considered illegal because cattle were being raised within Indigenous land. A Federal Court granted the request, but the decision was overturned in March by Federal Judge Diogo Negrisoli Oliveira, who again authorized the issuance of permits to transport cattle between properties located in the rural settlement of INCRA, Brazil’s land reform agency, pointing out that “there is a difference between those who have titles issued by INCRA since 1980 and those who are really invaders with no title at all.”

In 2021, the Supreme Court (STF) had already ordered the eviction of invaders from Indigenous lands in a ruling that listed seven critical territories, including the UEWW IL. In January of this year, since the decision had not been enforced, Justice Luís Roberto Barroso — the rapporteur of the case — issued a new order to investigate and punish those responsible for noncompliance with court orders.

The CAR has become some sort of parallel notary office, which is supposed to certify compliance with environmental legislation without verifying it.

Márcio Santilli, environmentalist and Indigenous peoples expert

In his decision, Justice Barroso pointed out that the administration of former President Jair Bolsonaro presented “non-credible” information about Indigenous lands and claimed that the government faced budget difficulties in complying with the decision. He set a new 60-day deadline for the federal government to present a complete plan for removing invaders from the seven territories mentioned in the lawsuit.

On June 7, the Ministry of Justice issued an ordinance authorizing the National Force to provide Funai with support to evict non-Indigenous people from the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Territory. In addition to livestock, the IL is also the target of land-grabbing and illegal logging.

So far there is no information available about the actions authorized by the courts or if the eviction teams will act in the Burareiro area.

Different views at INCRA

Burareiro is the name given in 1975 to the first Targeted Settlement Project of INCRA, in what was then called the Federal Territory of Rondônia. At the time, the military government settled 1,500 families that would plant cocoa — the term burareiro refers to the rustic buildings used to process the fruit.

The final demarcation of the Indigenous land was a long process full of conflicts over road opening, mineral extraction and timber theft. It was only concluded in 1991, when then-President Fernando Collor (1990-92) officially confirmed 1.8 million ha (4.4 million acres) for the exclusive use of Indigenous peoples.

The 115 land titles of the Burareiro rural settlement project should have been canceled as determined by the Brazilian Constitution (1988), which states that “acts with a view to occupation, domain and possession” of Indigenous lands or those authorizing “exploitation of the natural riches of the land, rivers and lakes existing therein are null and void.”

The Burareiro area includes Indigenous cemeteries and sites that are sacred to people who lived there historically but who are no longer able to reach that part of the territory because of fear. “Indigenous people have been avoiding going out alone for fear of attacks, and they avoid that Burareiro area,” said Neidinha da Kanindé.

Indigenous people have been avoiding going out alone for fear of attacks, and they avoid that Burareiro area.

Neidinha da Kanindé

In 1983, anthropologists Betty Mindlin and Mauro Leonel pointed out that forced contact with the then-new occupants brought from other parts of the country generated conflicts and significant reduction in the Indigenous population: “The least-affected populations were reduced by half,” they warned.

Nine peoples live in the UEWW IL. In addition to the Jupaú — also known as Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau — the Amondawa, Oro Win and isolated Indigenous peoples of at least two groups live there.

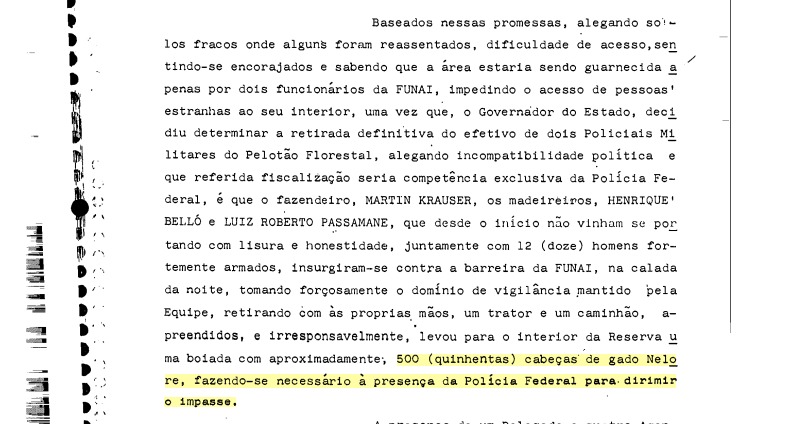

In April 2023, INCRA, Funai and the newly created Ministry of Indigenous Peoples met to address the conflict. At the meeting, INCRA’s director of land governance João Pedro Gonçalves pledged to seek a solution to remove “18,000 head of cattle belonging to people who claim to own public land, who claim to own Indigenous land.” Gonçalves, who represented INCRA’s president at the meeting, said the conflict is the result of a historic mistake that “cannot be left under the rug.”

“INCRA will hold working meetings to enter the area and solve this issue, this mistake, because that was already Indigenous land,” Gonçalves said before members of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous people.

In a note sent to InfoAmazonia, INCRA’s superintendent in Rondônia Luiz Flávio Carvalho Ribeiro took another approach to the conflict and said the agency would await a court ruling to “act accordingly” (read the full note).

The Ministry of Indigenous Peoples reported that INCRA had undertaken to present a survey of the occupation of that indigenous land by June 19, but the meeting to address the matter was canceled.

According to anthropologist Tiago Moreira from ISA, illegal occupation of Indigenous land increased in that area because control has been loosened in recent years, leaving the territory vulnerable.

“This invasion and the permanence of the invaders in the Indigenous land also sends a message to others planning to invade the territories and calls into question the limits of Indigenous peoples’ areas in the Amazon,” Moreira said.

This invasion and the permanence of the invaders in the Indigenous land also sends a message to others planning to invade the territories and calls into question the limits of Indigenous peoples’ areas in the Amazon.

Tiago Moreira, anthropologist from ISA

French vigilance

The lawsuit filed by Indigenous peoples against the Casino group is the first case of a supermarket chain taken to court in France under the Vigilance Law for deforestation and violations of human rights in the Amazon.

In June 2022, Indigenous organizations in Brazil and Colombia refused mediation — when an honest broker facilitates an amicable solution between the parties — as they consider that the lawsuit is in the public interest and cannot be resolved in closed-door negotiations.

“The leaders didn’t accept mediation because they understand that this is not just a financial matter; it’s about the very existence of the communities and the forest. And that corporations must understand that their supply chains directly affect the lives and rights of the Indigenous peoples who live there,” pointed out Indigenous lawyer Cristiane Soares from the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations in the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB).

The leaders didn’t accept mediation because they understand that this is not just a financial matter; it’s about the very existence of the communities and the forest. And that corporations must understand that their supply chains directly affect the lives and rights of the Indigenous peoples who live there.

Cristiane Soares, Indigenous lawyer from the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations in the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB)

According to a CCCA survey that supported the 2021 lawsuit, 25,482 animals were illegally managed at the UEWW IL in 13,411 ha (33,139 acres) of deforested area.

An economic report prepared by the Conservation Strategy Fund at the request of the CCCA estimated that the French group’s supply chain caused material damages of 54.3 million euros (about $60 million according to current exchange rates) to the Jupaú, Amondawa, Oro Win and uncontacted Indigenous peoples. However, the intangible damages — which include demographic loss, lower chances of self-determination, reduced ecosystem services and risks and extinction of entire groups — may be even worse.

For Cristiane Soares, “the slow pace of proceedings in French courts has somehow contributed to increase violations in Indigenous lands.” She pointed out that “so far there has been no effective action to change the situation.” The case is now awaiting an evidentiary hearing, which has been postponed twice.

In Brazil, lawmakers introduced Bill 572/22, which creates the National Framework Law on Human Rights and Business. In addition, a conduct adjustment commitment (known as TAC) was signed with large meatpacking companies in 2009, precisely as an alternative to legal action as long as the companies commit to not buying products coming from deforested or protected territories.

However, meatpackers have not adopted transparent and reliable supply chain monitoring so far. For example, the tools available on JBS’ website for tracking the origin of its products only allow identifying direct suppliers and do not disclose the original source of the animals and the farms they passed through.

Forest guardians and local politicians

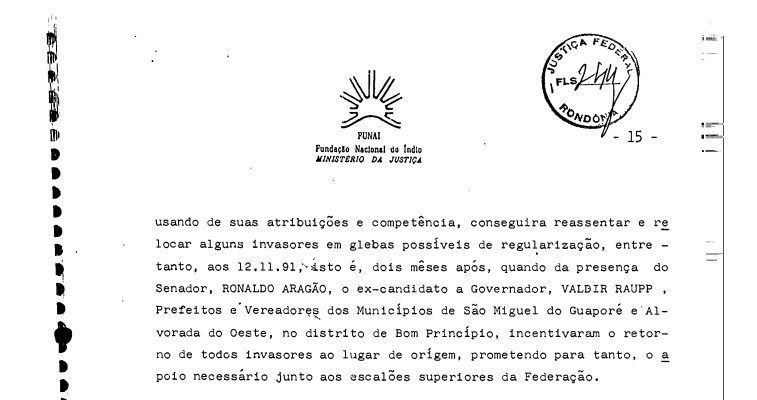

According to the lawsuit underway at the First Federal Regional Court, INCRA would have removed some families from the Indigenous land in 1991 and resettled them elsewhere, but the farmers received help from influential local politicians to return to the area.

In 2017, politicians from Rondônia participated in a meeting on the Indigenous land where they promised to regularize the area for rural producers. One of the participants was current Federal Deputy Lucas Follador (PSC-RO), who represented his father — then-State Deputy Adelino Follador, a member of the União Brasil party. State government officials and representatives of environmental agencies also attended the meeting, which took place at an abandoned FUNAI base.

During the anti-Indigenous administrations of Bolsonaro (2019-22) and Rondônia Governor Marcos Rocha (União Brasil party) — who is still in office — invaders kept their hopes of regularizing the area.

“Local politicians in Rondônia have a well-articulate discourse against Indigenous peoples and conservation units. In recent years, we have seen roads appearing in this part of the Indigenous land, very close to two villages of the Jupaú peoples, which also poses risks to all Indigenous peoples who use that land, including uncontacted ones,” said anthropologist Tiago Moreira.

After several attempts to remove the occupants of the Indigenous land, only in 2004 did Funai file a lawsuit demanding repossession. The lawsuit was dismissed in 2014, since it failed to point out the occupants that would have their land expropriated. The Federal Prosecution Service appealed, and the case has awaited a decision from the First Federal Court since 2019.

Since the government did not protect the territory and invasions have increased in recent years, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau decided to surveil the land themselves by creating a group of people — the Guardians — that took turns protecting the territory. In several operations, the Indigenous people expelled invaders and handed evidence over to the authorities.

On April 18, 2020, Indigenous leader Ari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, who was a member of the Guardians surveillance group, was murdered in Jaru, outside the Indigenous land. While the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau linked the case to invasions of the territory, the Federal Police ruled out a connection between that crime and Indigenous resistance, and the case was sent to a state court to be judged as homicide for “futile motives.”

Ari was a teacher, and his death continues to reverberate in Rondônia and elsewhere. In 2021, Txai Suruí denounced the killing of her personal friend at the opening of the COP26 U.N. climate conference in Scotland.

In January, artist Mundano painted a 618-square-meter (6,652-square-foot) panel in the center of São Paulo, which was dedicated on the city’s anniversary.

Casino suggests that JBS is responsible for its indirect suppliers

When questioned, the Casino Group informed in a note that its suppliers are required to detail the supply route and that “it directly rechecks all farms based on batches in order to verify their socio-environmental compliance.”

However, the group said it would be up to meatpackers to monitor indirect suppliers in line with their Socio and Environmental Beef Purchasing Policy.

“As for indirect farms, supplier meatpackers must set identification and monitoring targets for their entire supply chains, so as to enforce the same socio-environmental criteria applicable to direct supplier farms. In addition, it points out that monitoring and full traceability policies must be in effect by 2025 at the latest. GPA [the Pão de Açúcar Group, which is responsible for Casino’s operations in Brazil] is involved in actions and working groups monitoring these farms.”

We sent a list of farms located in the Indigenous land and included in the Casino group’s supply chain and informed that some properties had transferred animals indirectly to meatpackers. However, the company stated that none of the farms mentioned were in their “bases.”

Regarding the progress of the case in French Justice, the group also informed that it still favors the mediation proposed by the judge and rejected by the Indigenous people, who want a public trial.

“It is worth noting that the judge proposed and continues to propose a process of mediation between the parties, which the plaintiffs declined, while Casino remains in favor of such a mediation procedure” (read Casino’s full note).

JBS says it has no control over indirect suppliers

In a note, JBS reported that the Aryane farm — which received cattle from the Indigenous land — was blocked from the list of suppliers. We sent information from the GTAs and georeferenced data on the farms found in the group’s supply chain. But the company stated that it “cannot monitor the other links in its supply chain” and therefore is not able to know the origin of the cattle coming from indirect suppliers, including animals from Indigenous lands and other protected areas in the Amazon.

Read JBS’ complete statement:

“The Aryane Farm is blocked. As for the other properties that directly supply JBS, they all complied with the Federal Prosecution Service’s Cattle Suppliers Protocol (Boi na Linha) at the time of their sales to the company. Technical Note 2, available on page 37 of the regulation, is important for understanding which cases of overlap require the producer to be blocked. Regarding the farms that, according to InfoAmazonia, would supply cattle to JBS suppliers, the company stresses that it cannot monitor the other links in its supply chain since Animal Transit Registrations are protected by secrecy under Brazilian law. So much so that it had to request the producers’ data from the reporter so that JBS could understand the case. Precisely to overcome this challenge to the industry, JBS implemented a tool based on blockchain technology. As of January 1, 2026, only producers registered on that tool will be able do business with the company.”