With pressure on their native land and traditional foods, agrochemicals polluting their rivers, and a high rate of chronic disease have left the Xavante people of Brazil’s Cerrado savanna vulnerable to the pandemic.

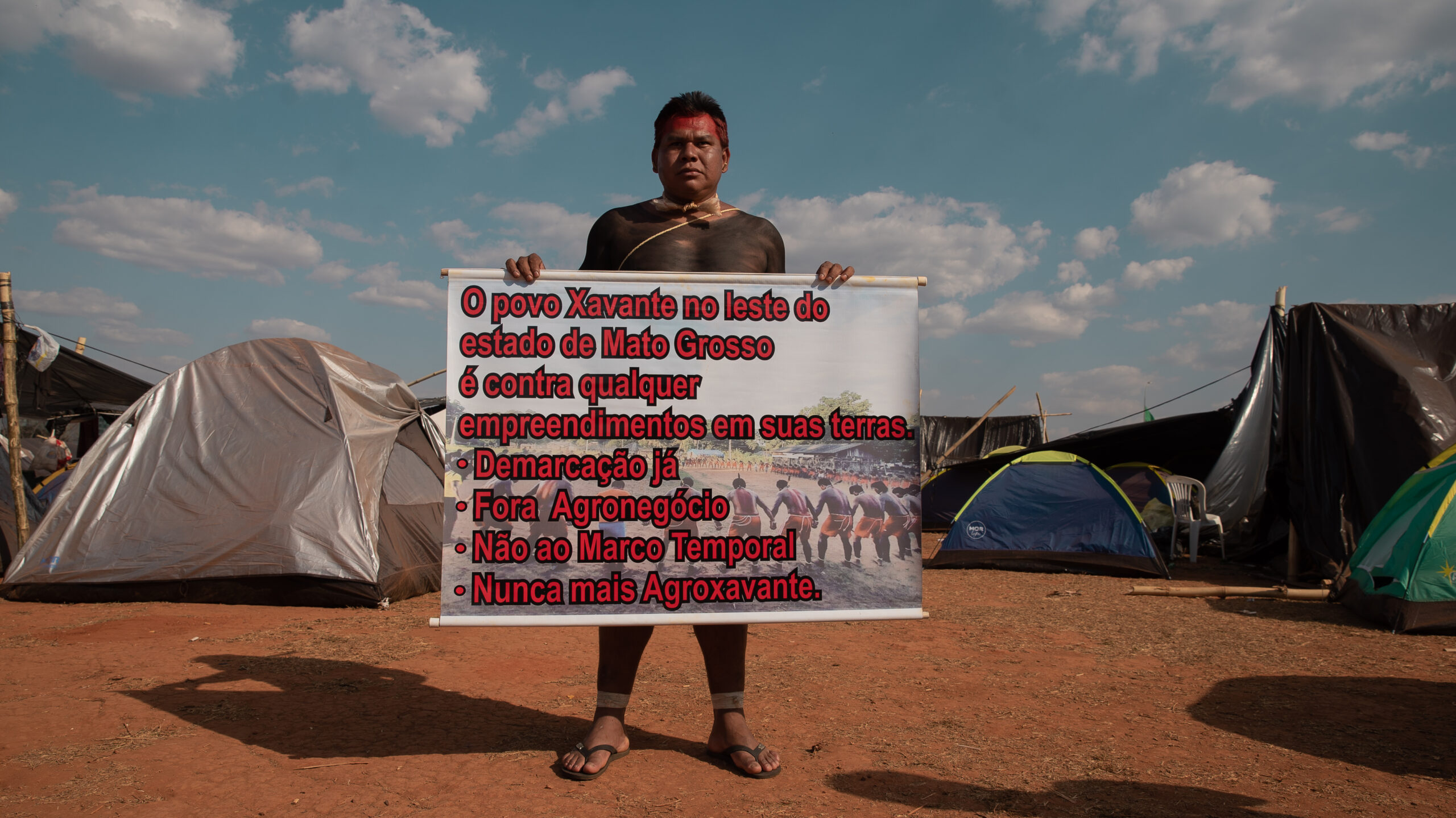

Beneath the intense sun of Brazil’s Central-West region, protesters paraded their bodies painted black and red — with charcoal and annatto, from the urucum (achiote) plant — and adorned with earrings and bracelets. They carried banners that read, “The Xavante people are not agribusiness. Free land,” and “The Xavante people are against Law 490 and marco temporal.”

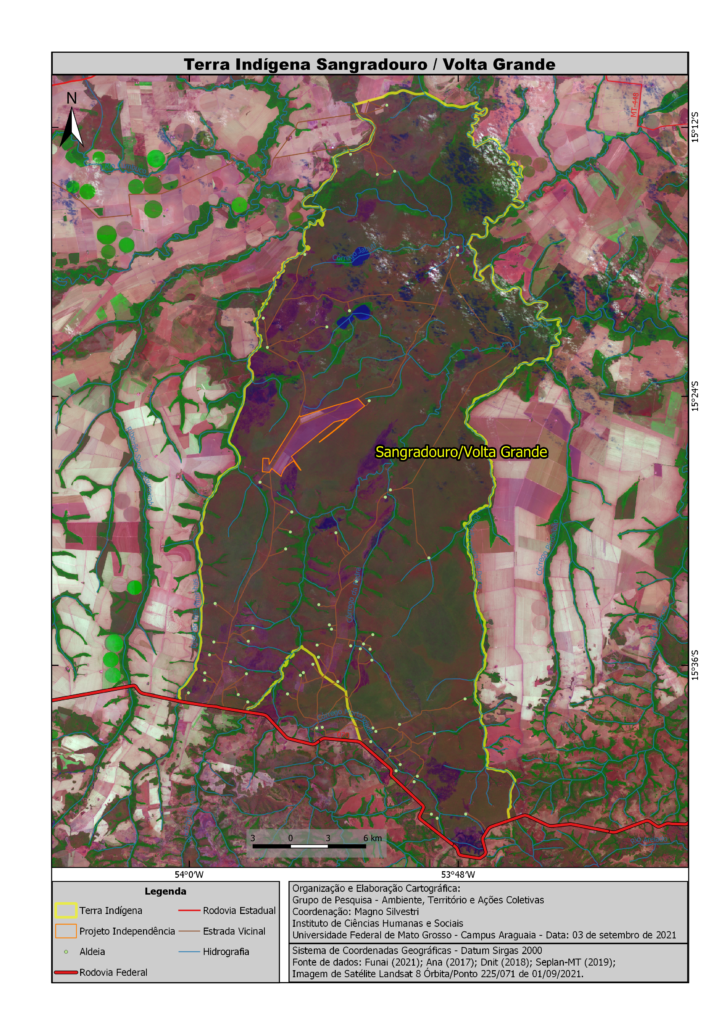

Neither the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been devastating for the Indigenous Xavante, nor the approximately 800 kilometers (500 miles) that separate their Marãiwatsédé Indigenous Territory from Brasília, could keep them from protesting in Brazil’s capital in August. Chief Carolina Rewaptu from the Marãiwatsédé reserve and Hiparidi Top’tiro from the Sangradouro reserve — two of 10 Xavante territories recognized by the federal government in the state of Mato Grosso — were among those who participated in the “Luta Pela Vida” (“Fight for Life”) campout in Brasília. The event was organized to oppose the so-called marco temporal policy, under which the government may deny territorial claims by Indigenous people whose ancestral lands were appropriated before 1988, the year Brazil’s current Constitution was promulgated.

The Xavante protesters were also demonstrating against the Agro Xavante project, a joint initiative by farmers from the Primavera do Leste Rural Association, the Mato Grosso state government and Funai, the federal agency for Indigenous affairs. Proponents of the project say it will bring industrialized agricultural activity into Indigenous territories, as well as “development, food security and quality of life” to the Xavante people. Given all these pressures, Top’tiro explained why the protesters chose annatto and charcoal to paint their skin: “Urucum and charcoal used to be used for war. We are at war with the government. That’s the reason,” he said.

As agribusiness has hemmed in Xavante lands in recent decades, areas traditionally used for farming, fishing and hunting have diminished. Today, their territory is composed of small islands of green in a sea of soybean plantations and cattle ranches. The Agro Xavante project, they say, represents yet another threat to the existence of these small green areas. “With the arrival of agribusiness inside our territory, things have gotten much worse,” Top’tiro said. “Many people say we are exaggerating, but areas that were once refuges for animals are being destroyed. And we will lose age-old traditional knowledge about medicinal plants. They will disappear.” [See the article Incentivados pela Funai, projetos de monocultivos avançam sobre territórios indígenas no Mato Grosso e dividem Ministério Público]

Map of the Xavante DSEI includes the 10 indigenous lands recognized by the Union, although the health district also serves the Xavante population living in indigenous lands still pleading for this recognition. Move the slider to compare land use and land cover in Mato Grosso in 1985 (left) and 2020 (right).

As soybean farming has intensified in the regions surrounding the Indigenous territories, said Carolina Rewaptu, there are no longer natural resources available to her people to make their handicrafts, nor are there medicinal roots to treat their illnesses. “Before, the landscape was very thickly covered. Much has changed now. We see these changes,” said Rewaptu, who was born in 1960, the start of a decade when the occupation of native lands for farms intensified under the Brazilian government’s colonization project, which was strongly supported under the military dictatorship.

The loss of their territory has also affected traditional Xavante eating habits, which have been slowly replaced by processed products. Nutritional and health-related vulnerabilities among the Xavante brought on by agribusiness-driven environmental damage have become particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the Xavante population one of the ethnicities that lost the most lives to the virus.

Territorial destruction and high mortality rates

The high mortality rate among the Xavante has drawn the attention of medical researchers. The special district for Indigenous health, or DSEI, serving the Xavante recorded a rate of 341 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants between the ninth and 40th weeks of the epidemic, corresponding to the period between Feb. 23 and Oct. 3, 2020.

In comparison, the overall Brazilian mortality rate was 69.5 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants during the same period. In other words, the lethality of COVID-19 among the Xavante population was nearly five times greater than among the general population. These figures are part of a study published by researchers at the Amazonia Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) — part of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), the leading medical research institute in Brazil — and other organizations using data compiled by the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations in the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB).

We managed to show a direct correlation between the devastation [of certain Indigenous territories] and the incidence rates in the territories we evaluated.

Paulo Basta, epidemiologist, Fiocruz.

The study also points to the high discrepancy between the number of deaths reported by the Ministry of Health’s Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health (SESAI) and the data compiled by COIAB. While SESAI reported that 330 Indigenous people have died during the period, COIAB reported 670 deaths. Among the factors explaining this difference is the fact that many Indigenous people who died from COVID-19 were not classified as Indigenous, but rather as mixed-race individuals, especially those who were infected and died in urban areas.

But the study goes beyond pointing out the underreporting by the Ministry of Health. Study co-author Dr. Paulo Basta, an epidemiologist and Indigenous health specialist, said, “We managed to show a direct correlation between the devastation [of certain Indigenous territories] and the incidence rates in the territories we evaluated.”

Basta says one of the main points of the study was to point out “how external threats can contribute to the spread of the pandemic on Indigenous lands.” These external threats include illegal logging and mining operations, land grabbing inside Indigenous territories, and the effects of burning carried out to clear land for farming and ranching.

Basta highlighted how these specific realities in Indigenous territories served by four DSEIs influence the high mortality rates found by the study.

In the Alto Solimões DSEI, centered around the municipality of Tabatinga in Amazonas state, Paulo Basta attributes the high mortality rate to the inadequate hospital infrastructure, which depends on the state capital of Manaus. It takes nearly two hours by plane or four days by boat (the form of transportation that’s much more accessible to the general population) to travel the 1,100 km (680 mi) from Tabatinga to Manaus. There’s a similar lack of health infrastructure in the Xavante and Cuiabá DSEIs, both in Mato Grosso state, and the Kayapó DSEI, in Pará state, along with other exacerbating factors, Basta said.

“The high rate of underlying medical conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes are associated with the negative outcomes to infection by COVID-19,” he said.

He traced these health problems to the change in the diet of Indigenous communities. “These Indigenous populations began eating processed food with low nutritional value, high in sugar, salt and fat, as they established contact with non-Indigenous society. This happened because the land they had always used for acquiring traditional foods (fish, game and plants) was being destroyed and natural resources became scarce.”

The dietary change is part of a larger cultural transformation driven by increased contact with non-Indigenous society. But this contact has historically gone, and continues to go, hand in hand with a destructive process transforming the Amazon rainforest and the Cerrado savanna into regions suitable for cattle ranching and soybean farming.

For the affected Indigenous communities and the epidemiologists specializing in Indigenous health, it’s clear that environmental degradation from expanding agribusiness is a key factor in the high mortality rates among the Xavante during the pandemic. The reduction in hunting and gathering areas, combined with the impact of agrochemical runoff in rivers resulting from intensified planting of monocultures over the last 36 years, have created environmental conditions that make the Xavante more vulnerable to public health threats like COVID-19.

The loss of food security, poorer nutritional quality and inadequate health care mean that illnesses take hold more easily and are more lethal for the Xavante, and COVID-19 has been no different, according to Aline Alves Ferreira, a nutritional epidemiologist who carried out her doctoral research at FIOCRUZ among the Xavante. “We already have indicators regarding health and food that are much worse than those of non-Indigenous people in Brazil. This was only accentuated by COVID.”

Ferreira attributed less of the blame on preexisting health factors and more on poor medical care, lack of basic sanitation, and environmental conditions created by agribusiness that have a direct effect on the way people eat. She described the Xavante territory as comprising “all these fields: soybean, soybean, soybean, soybean. Then, suddenly, when you get to the border of the Indigenous land, the vegetation changes completely.”

She said the shrinking natural environment and increasingly affected ecosystem mean increased consumption of ultra-processed foods, which in turn exacerbates the problem of poor nutrition. At the same time, access to nutritious food is also decreasing, she said.

Yesterday’s food, today’s food

From her home on the Marãiwatsédé reserve, Carolina Rewaptu recalled how, when she was a child, the women were responsible for collecting fruit like pequi (Caryocar brasiliense) and buriti (Mauritia flexuosa) from the Cerrado. They also collected roots like potatoes, yams, pumpkins and cassavas.

“It was good for us,” she said in a telephone interview about the Xavante diet. “These old foods were healthier. It was food from the countryside. It was important for the health of the children, the teenagers, and the young pregnant women.” The older people passed along these eating customs together with the knowledge for caring for children and preparing meals and rituals to the younger generations, Rewaptu said.

But in recent decades, things changed. “Today, they put sugar, salt and oil in everything. We didn’t eat sweet foods in the past.” She said that in her youth, children were healthier, with stronger physiques. “Today, the children are very fat. Things have changed and many people have diabetes because of this food that comes from the city. There is great concern about the Xavante people,” Rewaptu said.

Things have changes and many people have diabetes because of this food that comes from the city. There is great concern about the Xavante people.

Chief Carolina Rewaptu, from IT Marãiwatsédé.

The spread of agribusiness around the Xavante territory even impacted their wedding rituals, which are fundamental to the organization of the society and to their identities as Xavante. “Because there is so little game to hunt, we nearly lost the wedding ritual in which a meal of tapir meat is served to the entire community. We used the tapir because it’s our main fat meat. But then there were no more [tapirs] because our territory was cut off and devastated,” Rewaptu said.

The wildlife themselves “began getting sick because they ate soybean and corn. We know the animals are eating soybean because it makes them very fat. And then we eat really fatty meat. And they are also contaminated with the poisons” — the agrochemicals used in fertilizers and pesticides, which also contaminate the water that runs through the Indigenous land. “It’s more polluted in the rainy season, more dangerous, because the perimeters of the farm are all around us,” Rewaptu said.

Hiparidi Top’tiro, the chief of the Sangradouro reserve, said that “since the farming has come close to our territory, the poison they use is contaminating our food. Even what we plant inside our territory is contaminated.”

The Xavante’s relationship with food boils down to two concepts important to them as a culture: danhiptedezé, the foods and behaviors that make people stronger; and danhip’uwazé, those that make people weaker. “When women collect potatoes together in the Cerrado, for instance, they form a connection with the spirit of the food. The fact that you took it out of the Cerrado nourishes you and strengthens you,” Top’tiro said. When they hunt, the animal’s body carries a spirit. “This is a way to contribute to our spirit, from the women. Without hunting, there is no food to generate more children. Without hunting, there is no more pregnancy,” he said.

Fish and fruits, like buriti, jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril) and baru (Dipteryx alata), are foods that make people stronger. Foods that make people weaker are those that are processed, brought in from outside, and have no spirit. “This is what we know weakens our spirits,” Top’tiro said.

Danhiptedezé: the foods and behaviors that make people stronger; e danhip’uwazé: those that make people weaker

But he said the Xavante people’s weakest point, what makes it the most vulnerable, is its fragmented state. “If our land was all together, the situation would be easier. This wouldn’t all be happening,” he said.

Maria Lúcia Cereda Gomide, geographer and professor of anthropology at Rondônia Federal University, attributed this fragmentation of Xavante territory to a lengthy demarcation process in which disputes with farmers between the 1950s and 1970s made it impossible to establish one contiguous territory, like the Haiti-sized Xingu Indigenous Park in the north of Mato Grosso.

According to data compiled by COIAB, the four Xavante territories most affected by the pandemic were the reserves of São Marcos, Sangradouro, Marãiwatsédé and Pimentel Barbosa. Seventy percent of Marãiwatsédé, the reserve that’s home to Carolina Rewaptu, is located in the municipality of Alto Boa Vista, according to data from Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), an NGO that advocates for Indigenous and environmental rights. Data from IBGE, the federal statistics agency, show that between 2004 and 2019, there was a sharp increase in land allocated for soybean plantations in Alto Boa Vista, while areas dedicated to growing cassava nearly disappeared.

And data from the MapBiomas mapping platform show that between 1985 and 2020, forested areas in Alto Boa Vista declined from 176,705 hectares to 99,404 hectares (436,648 acres to 245,633 acres), a loss of 44%.

To gain a broader perspective on the deforestation in the region where the Xavante live, we focused on the four Xavante reserves with the highest COVID-19 mortality rates. We then did a profile of the seven municipalities in which these reserves mostly lie: Alto Boa Vista, São Félix do Araguaia, Canarana, Ribeirão Cascalheira, Barra do Garças, General Carneiro and Poxoréu. All are in the state of Mato Grosso.

In 1985, there were 4.18 million hectares (10.33 million acres) of standing forest across these seven municipalities combined. In 2020, that number had declined to 3.01 million hectares (7.44 million acres) — around 25% forest loss in 35 years.

During the same period, land allocated for farming and cattle pasture more than doubled from 1.05 million hectares to 2.27 million hectares (2.59 million acres to 5.61 million acres). The planted area of soybean alone expanded from 17,748 hectares to 768,898 hectares (43,856 acres to 1.9 million acres) — a 43-fold increase.

Health outcomes worse among Indigenous people

The Xavante are not the only Indigenous people with poorer health outcomes than the Brazilian population in general. Other Indigenous peoples have similar numbers, evident mostly in infant and childhood mortality rates as well as hospitalizations for preventable illnesses.

“The indicators for Indigenous people are always less favorable when compared to any other race, including with African-Brazilians who have also been historically excluded, marginalized, etc.,” said Paulo Basta, the epidemiologist.

Infectious and parasitic diseases, tuberculosis, malaria and hepatitis, for example, are more prevalent among Indigenous people than in the general population, according to data. “These people have been treated like hindrances and obstacles to the economic development of Brazil for 521 years. Because of this, they are discriminated against and seen as marginals of society,” Basta said.

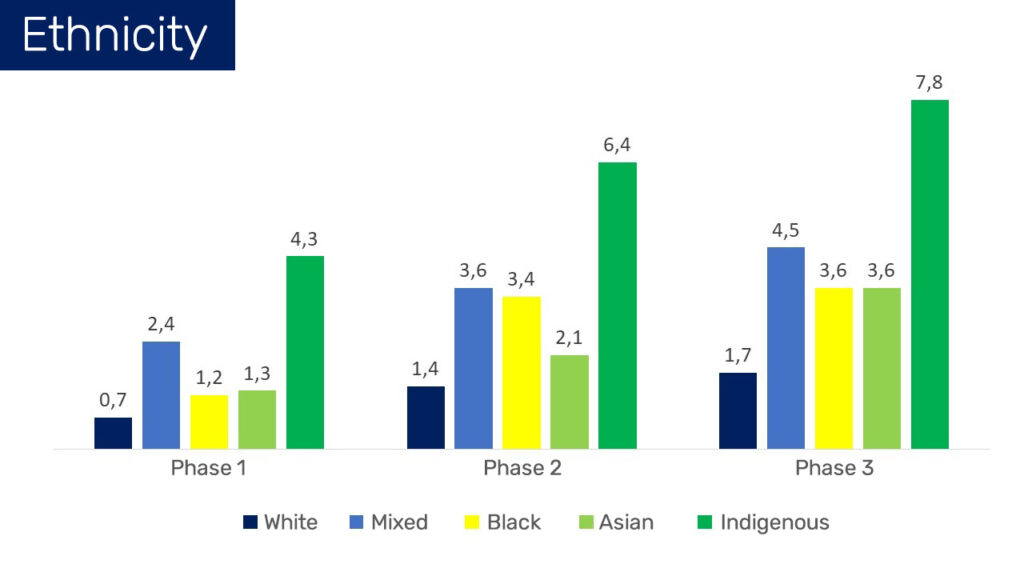

It’s a pattern that’s been repeated throughout the pandemic, according to data collected by Pedro Hallal, an epidemiologist and professor at Pelotas Federal University.

In testimony on June 24 before a Senate inquiry, Hallal presented a graph that he said was censored by the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro. It showed the results of a broad study that he coordinated, analyzing the prevalence of antibodies of people infected with COVID-19 according to race and ethnicity. The study found Indigenous people to have the highest rate of infection.

Basta points to the Xavantes’ situation, clinging to green islands lapped by soybean plantations on all sides, as a clear illustration for understanding the economic model that treats indigenous people as an impediment to development. He said the plantations that surround the territories bring no benefits to the Indigenous people. “They don’t build schools, they don’t offer job opportunities, they don’t create alternative development projects,” he said. Instead, he added, they expose the Xavante to an intense cocktail of agrochemicals.

In the Sangradouro reserve, for example, “the soybean plantations really run right up to the boundary,” said Maria Lúcia Gomide, the geographer. “So sometimes in the middle of the village we can smell the poison. And you see the airplanes flying over. It’s really quite invasive. The Mortes River, which is this really important river to the Xavante, is completely contaminated because the springs are all located on the farms.”

But the agribusiness operators now want to take things a step further, with a plan for industrial-scale farming inside the Xavante Indigenous lands.

The Mortes River, which is this really important river to the Xavante, is completely contaminated because the springs are all located on the farms

Lúcia Gomide, geographer.

Agricultural creep into Indigenous territories

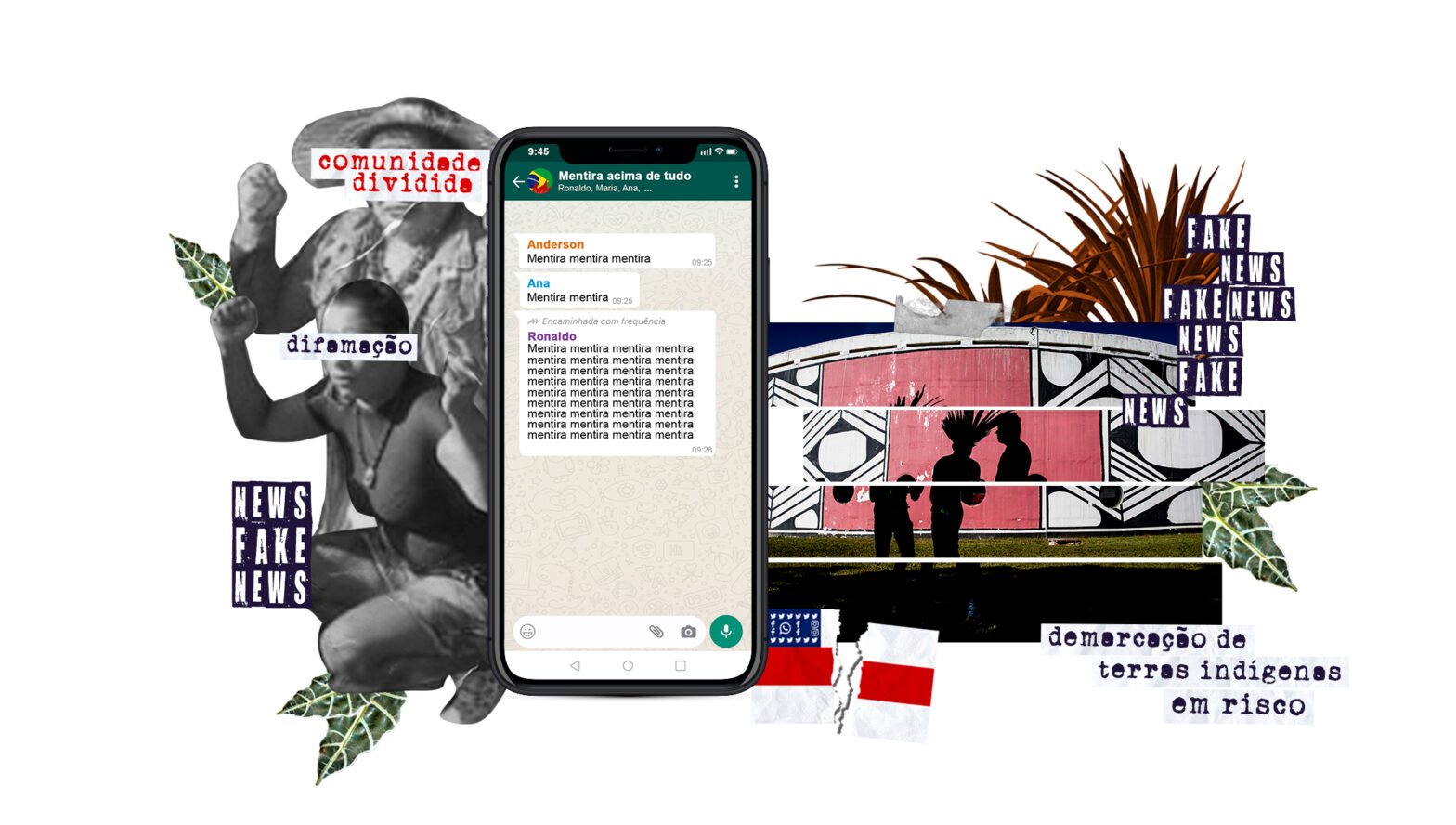

The “Agro Xavante” project, a rice monoculture project involving a farming cooperative inside the Sangradouro reserve, is backed by Funai, the Mato Grosso state government, and the Primavera do Leste Rural Association. The project was conceived by the agribusiness operators that already dominate the region surrounding the reserve, and has created a rift among the people inside it, with some in favor of the project.

Gomide said the Agro Xavante project could increase deforestation on Indigenous lands. “The area is already surrounded by cattle and soybean. The little bit of Cerrado left inside the reserve will be deforested, and there will be poison,” she said.

She added that, because the Sangradouro reserve has already been demarcated, any commercial farming within its boundaries by outsiders is unconstitutional.

“[Agro Xavante] flies in the face of [the Constitution] because Indigenous lands can’t be leased,” Gomide said. “They are intended for Indigenous use, but it must be common use. A parcel of it cannot be leased. So it is contrary to legislation.”

Basta refuted the arguments by proponents of the project that it will improve the food security of the Indigenous community, saying it could do just the opposite. Indigenous communities, living with limited or no access to electricity, don’t own refrigerators. As such, hunting or fishing is a routine activity, performed by the men, to obtain meat protein for the community. But if the men are employed in agriculture, as the project envisions, Basta warned that “the families could practically lose their access to protein because the father could stop bringing fish home, and stop bringing game home.” The community could also lose its ability to grow subsistence crops, since it’s also the men who clear the land for farming.

The Xavante and the experts agree that agribusiness’s impact on Indigenous health will worsen with the arrival of rice monoculture inside the reserve. As the project looms, the fight to keep traditional foods and bolster traditional cultivation methods becomes not only an act of resistance, but also pushback against the illnesses that come with colonization.

“We want to cultivate our land, we want to grow and bring back traditional food,” Hiparidi Top’tiro said. “I’m part of a group that is using traditional forest agriculture to feed our children and to combat diabetes and other types of sicknesses that affect our people.”

This report was produced in partnership with O Joio e O Trigo, and translated to English and published with Mongabay.