Exclusive survey reveals a much greater impact than estimated by agribusinesses. Ministry of Indigenous Peoples shows concern and demands consultation, but Lula’s minister of transport is optimistic about project launched by Bolsonaro.

A route of nearly 1,000 kilometres of railway that will traverse the centre of the country through protected areas and indigenous territories that are also home to isolated tribes. This is the Ferrogrão project (EF-170), a monumental undertaking that is the brainchild of major soybean and maize producers in West-Central Brazil, which promises to bolster the new outflow route through the country’s Arco Norte and reduce costs.

Production is currently transported by trucks using the BR-163 highway towards the ports located in the municipalities of Itaituba, Santarém and Barcarena in the state of Pará. Running parallel to the highway, the Ferrogrão line promises to reduce agricultural transportation costs, but it comes at a high price for traditional peoples and the Brazilian climate change agenda.

This is yet another case dividing Lula’s ministers. This time it is precisely in the state that will host COP-30, in 2025, when the president of the Republic would like to show off positive results in the fight against deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions.

If they do not consult us, we’re going to set up a village on the train line. Then we’ll see if they’ll go over the top of us.

Doto Takak Ire, president of the Kabu Institute

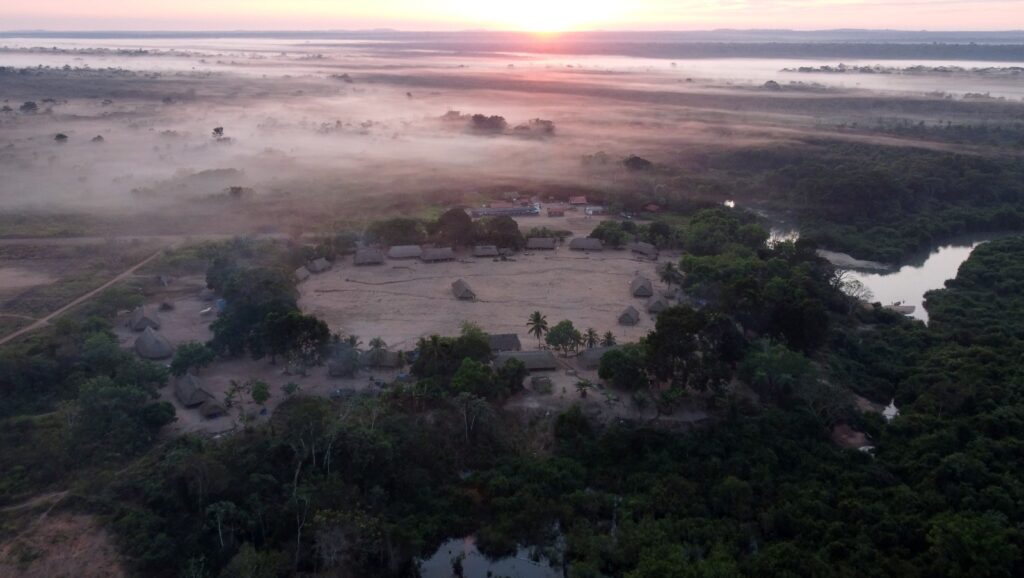

Doto Takak Ire, president of the Kabu Institute, which represents 12 communities of the Mẽbêngôkre-Kayapó people distributed throughout the Baú and Menkragnoti indigenous lands (ILs) and two communities from the Panará IL, stated for the report, “If they do not consult us, we’re going to set up a village on the train line. Then we’ll see if they’ll go over the top of us”. The territory is in the area most affected by the railway route, according to an exclusive analysis carried out by the InfoAmazonia Laboratory of Geojournalism. To make the situation worse, this is also the area used by three isolated tribes: Pu’rô, Isolados do Iriri Novo and Mengra Mrari.

The survey carried out as part of the report in partnership with InfoAmazonia and O Joio e O Trigo shows how, overall, at least six indigenous lands, which are home to approximately 2,600 people, and 17 conservation units, are in the demarcated area, which encompasses 25 municipalities of Mato Grosso and Pará, with an estimated population of nearly 800,000 people. Including a 10-km buffer zone around the territories, the railway will have an impact on more than 7, 300 km² of indigenous land and more than 48,000 km² of conservation units.

The analysis also considered a 50-km area around the Ferrogrão line, based on the route published in the Transport Information Database of the Ministry of Transport and the deforestation data of the Satellite Deforestation Monitoring Project in the Legal Amazon (Prodes [Projeto de Monitoramento do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal por Satélite]) of the National Institute of Space Research (Inpe [Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais]), for the period from 2008 to 2022.

This greater area of influence was based on the technical paper submitted by the Kabu Institute to Funai [National Indigenous People Foundation]) in November 2019, which draws attention to the pressures directly related to the BR-163 paving process in that area – and which could be exacerbated by construction of the railway line.

On the Pará side of the railway line, the paper states, a section of nearly 380 km (40% of the total length) is less than 50 km from the indigenous lands of Baú, Menkragnoti and Panará, “where deforestation levels have remained extremely high since paving of the BR-163 started”. The area of influence of the BR-163 highway is 40 km either side of the highway, as specified for this kind of undertaking in the Legal Amazon according to Inter-Ministerial Ordinance No. 60/2015.

The environmental impact study (EIS) for the Ferrogrão line, submitted during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency in November 2020, drawn up by the company MRS Ambiental, only considered two ILs within the undertaking’s area of influence: the Praia do Mangue and Praia do Índio reserves, located in the municipality of Itaituba and home to the Munduruku people.

The study was based on the Terms of Reference issued in September 2019 by the National Indigenous People Foundation (Funai) – chaired by Marcelo Xavier who is currently being investigated for a series of crimes committed against indigenous peoples, including the genocide of the Yanomami people. The document considers a distance of 10 kilometres around the railway line, in line with the measurement stipulated for this kind of undertaking by the aforementioned ordinance of 2015.

Asphalting went ahead under the Bolsonaro government, reaching as far as Novo Progresso by the end of 2019 and being completed up to Miritituba in February 2020. Although the Kabu Institute is in charge of the use of the resources under the Basic Environmental Plan (BEP), which is the main requirement stipulated in the environmental impact study for the highway, it has not received any federal transfers since 2020.

Between 2010 and 2019, the projects were jointly decided upon by the villages associated with the institute, with oversight by Funai, to which the indigenous peoples reported every six months. “It will soon be five years since the Bolsonaro government halted everything; that’s five years of violation of our rights”, Doto Takak Ire complained.

In May of this year, the Kabu Institute came to an agreement with the highway concession holder for an emergency transfer of resources while it awaits new studies from Funai to resume the Basic Environmental Plan.

Agribusiness project

With the commencement of the Miritituba Port operation in Itaituba (PA) in 2014 and the recently completed asphalting of the BR-163 highway, the outflow of grain from Mato Grosso through the ports of Pará increased from 5% to approximately 30%. According to estimates of the governor of Mato Grosso, Mauro Mendes (União Brasil [Brazil Union]), the Ferrogrão line absorbs 50% of the state’s grain production and reduces freight costs by BRL 50 per tonne.

The railway line, which links the municipality of Sinop, in the north of Mato Grosso, to Miritituba Port, was developed by the company Estação da Luz Participações (EDLP), which joined forces with the largest grain buyers – Bunge, Cargill, Amaggi and Dreyfus – to bring the project before the federal government in 2014.

After being taken over by the Dilma Rousseff presidency (PT [Partido dos Trabalhadores, Workers’ Party]), the Ferrogrão railway was made public by Michel Temer (MDB [Movimento Democrático Brasileiro, Brazilian Democratic Movement]), whose minister of Agriculture was the ruralist Blairo Maggi, owner of Amaggi. The undertaking made rapid progress under Jair Bolsonaro (PL [Partido Liberal, Liberal Party]).

Doto Takak Ire told us that the first representative to liaise with the Kayapó people in relation to the Ferrogrão project was in fact Maggi, during his term of office as senator in 2016. When Temer took over, the Kayapó people ceased to be consulted in relation to the undertaking.

“We did indeed talk to Blairo Maggi, who stated that the government would fulfill the compensation. Before the impeachment, we had a meeting with the senator. When the government changed, we lost the dialogue and couldn’t speak with anyone else. Not even with the Bolsonaro administration.”

Following a lawsuit by PSOL (Partido Socialismo e Liberdade [Socialism and Freedom Party]) in the Federal Supreme Court (FSC), justice Alexandre de Moraes brought the Ferrogrão processes to a halt in order to review the effectiveness of Law 13.452/2017, derived from a provisional measure proposed by Michel Temer, which reduces the area of Jamanxim National Park to accommodate the railway line.

The project returned to public debate with Moraes’s decision in May of this year to resume studies and administrative processes, and asking the federal government to carry out a conciliation regarding the environmental issues involved in the project. However, no commitment was made regarding reducing the conservation unit.

If it reaches Congress, which is completely averse to environmental issues and eager to enact reversals in this area, we are concerned that a draft law to deallocate Jamanxim Park, along with the hearing on the viability of the undertaking, would end up becoming the catalyst to deallocate many other conservation units in the region.

Biviany Rojas Garzon, coordinator of the Xingu Programme at the Socio-Environmental Institute

“It is a very specific decision, because it requests a conciliation but does not really clarify the purpose of the conciliation”, said Biviany Garzon, coordinator of the Xingu Programme at the Socio-Environmental Institute. It points to the risk of the discussion on the deallocation of protected areas returning to National Congress.

“If it reaches Congress, which is completely averse to environmental issues and eager to enact reversals in this area, we are concerned that a draft law to deallocate Jamanxim Park, along with the hearing on the viability of the undertaking, would end up becoming the catalyst to deallocate many other conservation units in the region.”

Moraes’s decision came precisely at a time when the ministries of the Environment and Indigenous Peoples had been weakened by the National Congress with the transfer of powers from those portfolios to the ministries of Justice and Agriculture. The idea of conciliation was also put forward by Moraes in a recent discussion in the FSC regarding the timeframe for the demarcation of indigenous lands.

Despite the strong emphasis on the environment that framed the formation of the current government, Renan Filho (MDB), the minister of Transport, has publicly defended the Ferrogrão line since he took office. He praised Moraes’s decision and stated that he intends to use the studies already carried out on the railway line and seek an agreement on the environmental issues surrounding the project in order to launch the call for bids as early as 2024.

However, the economic viability and environmental impact studies undertaken for the project have been subject to controversy, even within the government. The Ministry of Indigenous Peoples points out that consultation of the native peoples affected by the project was not considered in the Ferrogrão project.

The secretariat cites increased levels of harassment in villages by agribusiness, increased extraction of wood and illegal fishing in indigenous territories and protected areas, as well as increased difficulty for indigenous groups to have their territories recognised, as the main threats to the people living around the railway line.

The Ministry of Transport, contacted for the report, issued a memo stating that it was working alongside Infra S.A. and the National Land Transport Agency (ANTT [Agência Nacional de Transportes Terrestres]) on a detailed review of the needs to update and supplement the studies previously carried out, “prioritising socio-environmental issues”.

The consultation with the affected indigenous peoples was not considered, and it is a fact that the project in question is intended for the transportation of grains such as soy and corn, which was a priority for the two governments preceding the current one. The project began without taking into account the existing indigenous areas, as well as the indigenous peoples living there, and much less the possible presence of isolated and recently contacted peoples.

Secretariat of Environment and Indigenous Territorial Management of the Ministry of Indigenous People

The memo stated that by decision of Lula the ministry is taking steps to ensure that all its transport undertakings “are environmentally sustainable, comply with current legislation and also meet the needs of local communities”.

The text stated, “The same applies to the EF-170 project. The office will discuss the necessary environmental issues that must be addressed by all concerned areas of the federal government, such as the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, and Brazilian society”.

The Ministry of Transport listed the advantages of the undertaking as the reduction of CO2 emissions, reduction of freight costs, collection of tax revenues, job creation and “enhanced oversight actions against the illegal expansion of the agricultural frontier”.

In a memo sent for the report, the technical division of the Ministry of the Environment confirmed that the environmental impact studies submitted by the developer were sent back by Ibama (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis [Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources]) in March 2021 and the adjustments requested by the licensing team have not been submitted to date.

Pressure on the territories

Indigenous lands serve as a shield against the advance of environmental degradation in the region. Within the ILs, total documented deforestation is 9.19 km². If we consider the 10-km buffer zone, this number rises to 799.82 km² – an 8,703% increase. The report survey, based on Prodes data pertaining to the period between 2008 and 2022, found that more than 95% of the deforested area affecting the territories is concentrated around the municipality of Altamira, and affects the Baú (582.69 km²), Menkragnoti (159.38 km²) and Panará (23.11 km²) ILs, which are home to more than 80% of the indigenous population impacted by the project in the region.

On another front, Novo Progresso has the greatest concentration of deforested area in relation to conservation units accounting for more than 40% out of a total of 3,955.28 km² of protected areas cut down along the railway route. This is the municipality where Bolsonaro achieved the highest proportion of votes in the Amazon in the first round of the 2022 elections.

Cumulative deforestation between 2008 and 2022 came to approximately 10% of the 98,862 km² area examined by the report, according to Prodes data. Forty per cent of the total deforestation in this region was recorded in the last four years, coinciding with the Jair Bolsonaro government.

This region has suffered extreme levels of deforestation since the opening of the BR-163 highway. Mainly since it was asphalted, you can see deforestation vectors advancing in the direction of the conservation units and indigenous lands.

Juan Doblas, geospatial analyst at GlobEO (Global Earth Observation)

The BR-163 highway has led to deforestation in the territories

Months after asphalting the BR-163 highway to Novo Progresso, in July 2019, the municipality was the epicentre of the criminal act known as the Day of Fire, when supporters of the former president deliberately set fire to the forest bordering the highway. The fires spread to the municipalities of Altamira and São Félix do Xingu.

With a route running parallel to the Ferrogrão line, the area around the BR-163 highway – 40 kilometres on either side of the highway – accounts for a total of 80% (7,918.78 km²) of deforestation in the area analysed by the report.

“When the road was paved, deforestation accelerated, agribusiness accelerated, and it came into contact with indigenous land”, said Doto Takak Ire. “The mining prospectors arrived a long time before, together with the opening of the BR-163 highway. As the paving work progressed, loggers increased in number as well. There is a lot of pressure here. And now that agribusiness has arrived, it’s difficult for us to curb. This is having a major impact and is causing concern.”

In the last four years, the percentage of deforestation recorded by the municipalities in this area was more than double what was observed in the total area of each of them.

Municipalities with greatest deforestation in the area analysed

Juan Doblas, a geospatial analyst at Global Earth Observation (GlobEO) explained “This region has suffered extreme levels of deforestation since the opening of the BR-163 highway. Mainly since it was asphalted, you can see deforestation vectors advancing in the direction of the conservation units and indigenous lands”.

Along with researchers Mauricio Torres and Daniela Fernandes Alarcon, Doblas monitored the consequences in the territory during the highway asphalting process. In the book You own what you deforest: connections between occupation of untitled land and deforestation in south-east Pará (IAA, 2017), they show how the project created a land speculation dynamic that placed the municipality of Novo Progresso at the centre of deforestation of the Legal Amazon.

“This deforestation was caused by local merchants who took advantage of the construction of the BR-163 highway. It is very likely that a new undertaking, such as the Ferrogrão railway line, could cause a new deforestation cycle through similar mechanisms of land speculation and capitalisation”, Doblas pointed out.

The economist Mariel Nakane, technical adviser of the Xingu Programme at the Socio-Environmental Institute (SEI), who has been monitoring the Ferrogrão project since 2018, argues that the railway feasibility studies must consider the impact of the BR-163 highway, as well as the entire logistics corridor planned for the outflow of grains from the ports in Pará.

“This is a conflict-ridden region with high rates of deforestation, territorial disorder, and land conflict due to the paving of BR-163. What most affects indigenous lands are the impacts generated by the interaction of various projects in the area.”

Construction of the highway led to increased population density and occupation in the area around the Kayapó and Panará territories near the road.

The increased presence of outsiders around the territories is the main cause of deforestation occurring near the indigenous lands, Nakane said.

“In this context of lack of territorial governance and absence of state presence, this facilitation of occupation automatically transforms into an increase in land grabbing of public lands and illegal activities, negatively impacting these territories. It leads to an escalation of deforestation in the vicinity and invasions for illicit activities such as timber theft and mining.”

Kayapó Territory

With a population of approximately 1,450 inhabitants, the Baú and Menkragnoti ILs are located in the municipality of Altamira, near the border with Novo Progresso, and are home to the Mebengôkre Kayapó people, Mebengôkre Kayapó Mekrãgnoti people and three isolated tribes: Pu’rô, Isolados do Iriri Novo and Mengra Mrari.

In a report on the advance of illegal prospecting in the Kayapó territory, the Xingu+ Network pointed out that this activity has been one of the main vectors of deforestation in these territories. In mid-2020, it was found that an old landing strip had been brought back into service in the Menkragnoti IL, with approximately 84 km of tracks connected to the strip and to the gold extraction area, which were embargoed in operations by Ibama and ICMBio (Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade [Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation]).

This is a conflict-ridden region with high rates of deforestation, territorial disorder, and land conflict due to the paving of BR-163. What most affects indigenous lands are the impacts generated by the interaction of various projects in the territory.

Mariel Nakane, technical advisor of the Xingu Project at ISA

According to information from Sirad X, the Xingu+ Network monitoring system, in the last five years, six new prospecting hubs have been set up in the Baú IL, in addition to recommissioning and attempts to resume operations in old mines.

In this land, deforestation caused by illegal prospecting has seen unprecedented escalation in the last six years: according to Prodes, a deforested area of 3.08 km² out of a total of 3.68 km² deforested during that period.

Deforestation in the deallocated area of the territory

Part of the deforested area around the Baú IL was previously indigenous territory. Having been declared as owned by the Kayapó in 1991, the IL passed through an intense process of conflicts that prevented it from being physically demarcated until the end of the 1990s. That process was resumed in 2003 at the beginning of the first Lula administration.

To resolve the conflicts around the demarcation, the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF [Ministério Público Federal]) in Santarém (PA) enacted a conciliation and conduct modification agreement that shrunk the Kayapó territory by an area larger than Belgium (3,492.69 km²).

The process, which involved Funai, the Federal Police, the Prefecture of Novo Progresso, Kayapó indigenous leaders, associations of farmers, landholders and miners active in the region, was implemented by Ordinance No. 1.487/2003, signed by then minister of Justice, Márcio Thomaz Bastos.

Based on the new territorial boundaries, the IL demarcation and ratification process was concluded in 2008. What happened with the deallocated land of the Baú IL is symbolic of the deforestation pressure around the territory. In 2008, deforestation documented in the area that was no longer indigenous territory was just above 4% (141.40 km²). Over the next 14 years, more than 35% of this territory was felled (1,255.98 km²).

Munduruku Territory

Mining activities that reach the indigenous lands of the Kayapó people also affects the Munduruku people who live in the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Land, which straddles the Pará municipalities of Trairão and Itaituba, where more than 20% of deforestation in the area examined by the report is concentrated.

In April 2022, InfoAmazonia confirmed the presence of a mining dredge during a visit to the territory. The Sawré Muybu IL was recognised as indigenous territory by Funai in 2016 and has been awaiting physical demarcation as deforestation has increased in the territory. Of the 26.45 km² of deforestation documented by Prodes in the Ferrogrão area of influence, between 2008 and 2022, more than 70% (19.15 km²) occurred in the last six years.

Alessandra Munduruku, coordinator of the Pariri Indigenous Association, which represents the Munduruku people of Médio Tapajós, stated “We have been tackling the mining problem, and then a railway line comes along, bringing deforestation”. She stresses that the railway project should also consider the impact of the ports in Itaituba. “What stands out is the number of infrastructure projects, immense projects that are not developed with traditional peoples in mind; there’s no room for us in that infrastructure.”

Among the impacts already being felt in the territory, she mentions the construction of grain storage silos in Itaituba by the companies Bunge and Cargill, which are giving rise to land speculation in Itaituba. “Most communities are being pressured to sell land to those large companies.”

Alessandra Munduruku emphasises that the communities in the Sawré Muybu IL, as well as all the other indigenous peoples and traditional communities in the region, must be consulted about the project. “Consultation should take place in the village, with the people. The government needs to read the consultation protocols for indigenous peoples, because they are saying how they want to be consulted.” Like the Kayapó and Panará peoples affected by the project, the Munduruku people also have a consultation protocol.

Station in Matupá

The studies conducted to date only consider two loading and unloading points for the railway: at the start and end of the line. The Technical, Economic and Environmental Viability Study (EVTEA [Estudo de Viabilidade Técnica, Econômica e Ambiental]) completed in October 2015 by the company The Nature Conservancy (TNC) warns that changes to the original design, with the construction of intermediate loading and unloading sites or extension of the route, may mean there will be environmental and social impacts that were not addressed in the study.

The environmental impact study of the project, dated November 2020, takes into account the initial station in Lucas do Rio Verde (MT) with terminus in Itaituba (PA), but none of the studies consider intermediate stations when analysing the impact of the Ferrogrão railway line. However, the specifications of the undertaking, also dated 2020, provide for a scenario with a stop in the municipality of Matupá.

Juan Doblas considers that the intermediate station in Matupá could stimulate the cultivation of soybean near the Panará IL given the relief characteristics of the territory, which are favourable to grain cultivation.

We depend on the river to live. The headwaters of the Iriri River are within the farms. When it rains, the pesticides used in soybean plantations reach our rivers, contaminating the fish and our future.

Kunity Panará, Secretary of the Iakiô Panará Association

On the page presenting the railway project, the National Land Transport Agency (ANTT) says that the route suggested by the initial studies “will not be binding on the successful bidder”. Doblas warns of the risk that political and economic interests in the region could lead to the construction of other intermediate stations in the Novo Progresso region.

“There is no stop in Novo Progresso in the project, but the original project did not have a stop in Matupá either. This makes it quite clear that, under the right conditions, a new station could be built, which would cause the Novo Progresso region to become a hotspot, with groups interested in deforestation, a very large stock of forests and increasing farming of soybean. A new stop could ignite demand for land to plant soybean throughout the region because there are suitable areas.”

Panará Territory

The cultivation of soybean in the vicinity of the indigenous territory is already a concern for the Panará people.

“We depend on the river to live. The headwaters of the Iriri River are within the farms. When it rains, the pesticides used in soybean plantations reach our rivers, contaminating the fish and our future. In some villages, there are reports of Panará people experiencing itching, sores, and discomfort after bathing in these polluted waters,” says Kunity Panará, Secretary of the Iakiô Panará Association.

The association was founded in 2001 to defend the Panará IL, part of the ancestral territory that they won back in 1991 after decades of exile imposed by the opening of the BR-163 highway, which was permanently demarcated in 1996. Kunity said “Our grandparents and our parents went through a lot of distress with the construction of the BR-163 highway. We were expelled from our territory so that the highway could be built. We have been through a long fight to be able to come back after 20 years of exile”.

During the exile period, the Panará population was reduced to about 70 people. After returning to the territory, the population grew and currently stands at more than 700 people, close to the number documented before first contact with non-indigenous people in 1973.

Kunity, who also acts as spokesperson for the Xingu+ Network, asserted “We have already petitioned the Brazilian government and we hope the consultation will take place as soon as possible. The government has an obligation to consult us before planning any project that affects our lives. We have our consultation protocol, which must be respected by all”.

Impacts beyond the area analysed

A study conducted by researchers at the Remote Sensing Centre of the UFMG (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais [Federal University of Minas Gerais]) simulated the impact of an intermediate station in Matupá. By using the OtimizaINFRA model, which simulates transport logistics in Brazil, they concluded that the terminal could lead to a split in the contiguous blocks of the Xingu Park and Capoto Jarina ILs, due to occupation of those territories along the MT-322 state highway.

It is estimated that the Matupá terminal would increase traffic for soybean transportation on that highway from zero to an average of 174 trucks per year. “Therefore, any analysis of the environmental impact of the Ferrogrão railway line should consider the entire area of influence of the undertaking, and not only the 10-km area on either side of the line”, they emphasised.

“We are aware that it will not only have an impact in the area of influence. It will have a considerable social, environmental and economic impact. When the Ferrogrão begins, the tendency will be for the population to move closer to the indigenous territory”, said Ewesh Aura, legal adviser of the Xingu Indigenous Territory Association (ATIX [Associação Território Indígena do Xingu]), which represents 16 peoples in the region and is also part of the Xingu+ Network.

We have been demanding that the government conduct a consultation regarding all these territories that lead towards Ferrogrão. It will be very important for us to be part of this project because, often, we are excluded, and decisions are made without listening to us.

At the end of May, representatives of ten indigenous peoples and eighteen civil society organizations, organized under the Teles Pires Forum, gathered in Sinop, the city where the initial station of Ferrogrão is planned.

In the Sinop Letter, leaders of the Boe-Bororo, Enawenê-Nawê, Xavante, Nambikwara, Munduruku, Kawaiwete, Kayapó, Ikpeng, Terena, and Guajajara indigenous peoples advocate for a process of free, prior, and informed consultation with indigenous peoples and other traditional populations.

They increase the grain production projection as if Mato Grosso did not have issues with rising temperatures, reduced rainfall, and depletion of underground water reserves. Climate risk must be taken into account; we cannot assume that the environmental conditions for grain production will remain stable in the next 60 years.

Biviany Rojas Garzon, coordinator of the Xingu Program at ISA

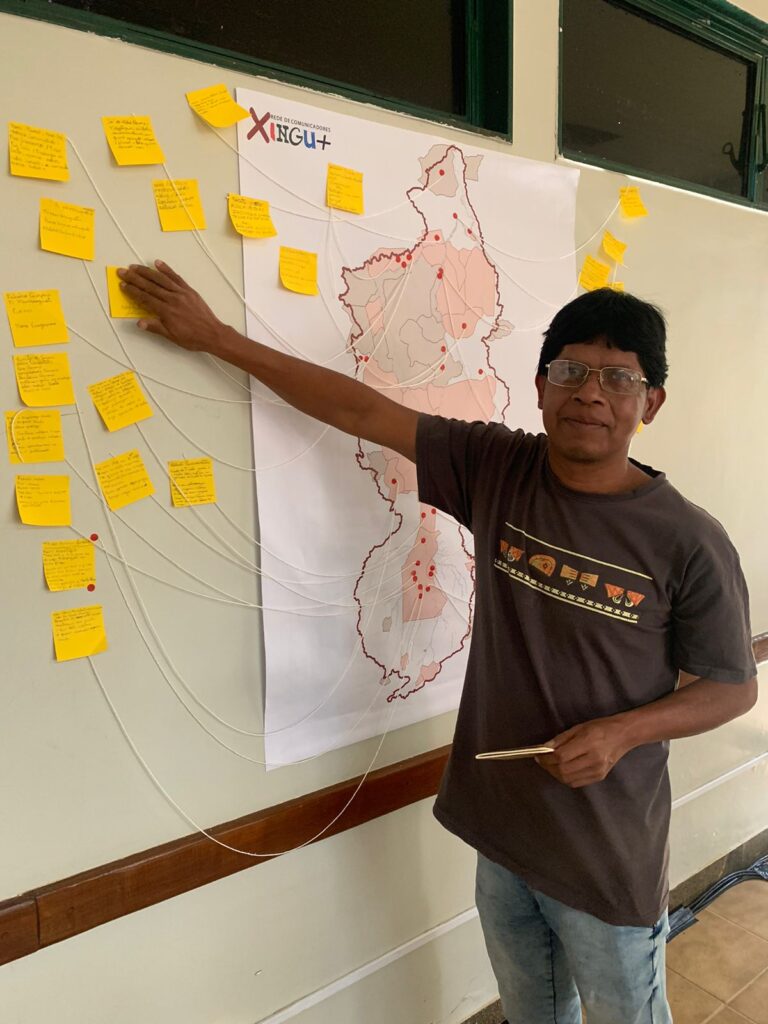

Since 2016, the Xingu + Network has been advocating for respect for Article 6 of ILO Convention 169, which establishes the right to consultation for traditional peoples.

“The free, prior, and informed consultation with traditional peoples and communities in the area of influence of this grain transportation corridor is essential for the government to consider when evaluating the feasibility of the project,” says Biviany Rojas Garzon. She is one of the individuals responsible for drafting the document “Guidelines for verifying the right to consultation and free, prior, and informed consent in the infrastructure investment cycle,” published in April of this year.

Garzon points out that the impacts of Ferrogrão are underestimated in the studies conducted for the project, which even disregard the climate risks over the 65-year concession period of the railway. “They increase the grain projection as if Mato Grosso did not have issues with rising temperatures, reduced rainfall, and depletion of underground water reserves. Climate risk must be taken into account; we cannot assume that the environmental conditions for grain production will remain stable in the next 60 years.”

With the resumption of the railway project, the Xingu + Network submitted a document to the TCU, ANTT, and Ministry of Transport reinforcing this demand and calling for a review of the technical feasibility and environmental impact studies conducted for the project.

The first step, according to Garzon, is to “clarify” the 10 km area of influence, which she considers “a factual error, a misinterpretation” regarding Ordinance 60/2015. “We request that the area of influence be redefined in the update of the feasibility study so that from there, indigenous peoples and traditional communities that need to participate in a process of prior, free, and informed consultation on the project can be identified.

What is the project’s area of influence?

Consulted by the news report, the Secretariat of Environmental and Indigenous Territorial Management of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples considers that the early stages of Ferrogrão already impact the nearby Indigenous Territories (TIs).

In a statement sent to the news report, the secretariat emphasizes the need to review the ten-kilometer limit and notes “much uncertainty” regarding the dimensions of environmental and social impacts that may affect Indigenous territories. “For an exact assessment, it is necessary to conduct a technical study of the location, considering that the impacts caused by the project can lead to irreversible and irreparable damage to the environment, as well as the way of life of the indigenous peoples in the vicinity, given the drastic changes in their social environment,” the statement says.

Based on Cartographic Analysis No. 550/15, the secretariat identifies 23 Indigenous Territories considered close to the railway’s route, with TI Manoki being the farthest at 224.94 km from the planned layout.

Indigenous Territories near the Ferrogrão route

This report was produced in partnership with O Joio e O Trigo and is part of the Geo-journalism InfoAmazonia Lab, conducted with the support of the Serrapilheira Institute, to promote and disseminate scientific knowledge and geographical data analysis in journalistic production.