The most vulnerable municipalities are affected by various types of crime

Queimada em área de desmatamento recente em Lábrea, agosto de 2020

Foto: Christian Braga / Greenpeace

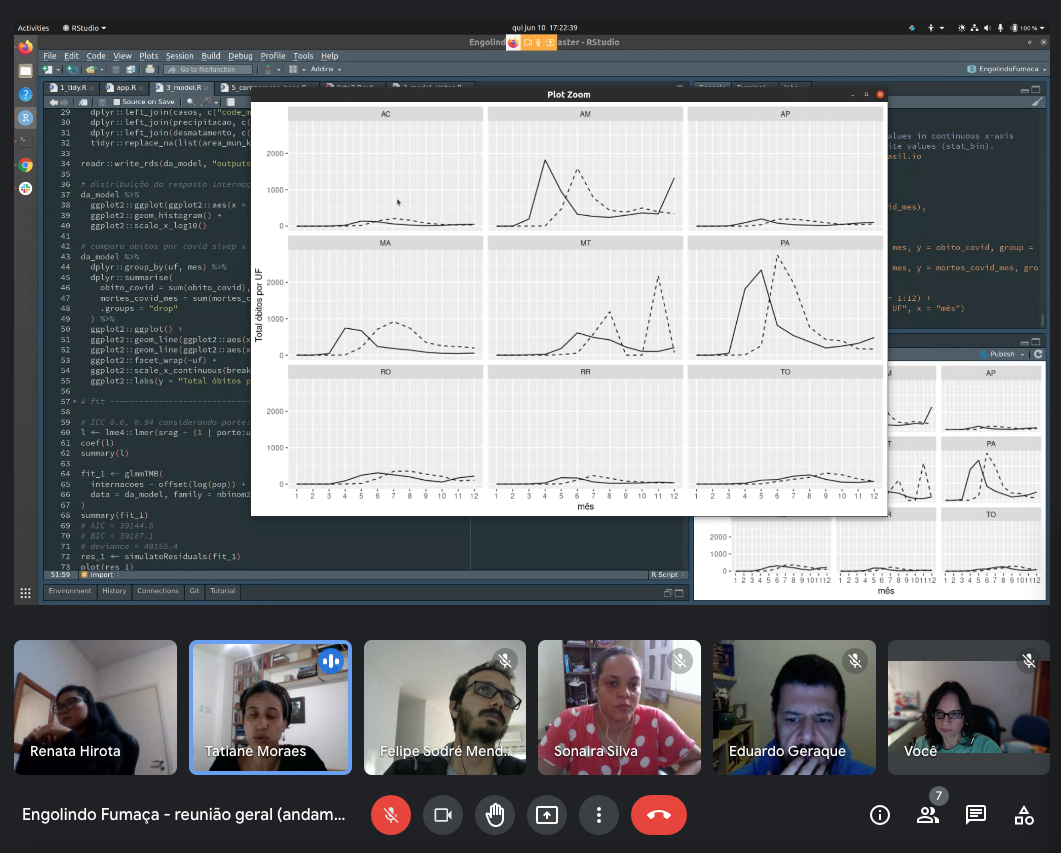

It’s not just fire that’s behind the smoke in the Amazon skies. If, on the one hand, the high concentration of particulate matter in the atmosphere in 2020 led to hospitalizations for Covid-19 and other respiratory syndromes, on the other hand, this same air pollution is one of the footprints left by a chain of destruction and socio-environmental conflicts. Amidst the haze of ashes, we can make out land grabbing, logging, the dark side of agribusiness, works of infrastructure, and assassinations of community leaders.

These processes can be seen at differing scales, in the region’s most vulnerable municipalities as identified in the InfoAmazonia analysis. These are ten cities in the Legal Amazon region, three of them in southern Mato Grosso making up part of the Pantanal biome. In this report, we continue our journey to the other seven, in the Amazon biome. Four in southern and southwestern Pará (São Félix do Xingu, Altamira, Itaituba and Novo Progresso), one in north-western Mato Grosso (Colniza), one in northern and north-western Rondônia (Porto Velho) and one in southern Amazonas (Lábrea).Using an interactive classification algorithm, these cities were grouped by profile similarity between July and October 2020, using data on fires, deforestation, precipitation, pollution, and population. Compared to other groups generated, these ten vulnerable municipalities had, more frequently, daily average levels of particulate matter above 25 micrograms per m3. This indicates a continuous exposure to a high level of pollution. These municipalities also had the highest average levels of deforested areas and heat sources.

“We are living through a pandemic in which the virus attacks precisely the respiratory system, people’s lungs. So, if you have populations in the Amazon that suffer from air pollution, this creates a situation in which these people have much lower resistance, which increases their vulnerability and the risk of Covid cases reaching critical levels with hospitalizations”, argues Antonio Oviedo, coordinator of the monitoring programme of the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA).

Loss and pressure in the Xikrin territory

It’s been almost a year since Covid-19 took the life of Chief Jaguar. That’s how Beptok Xikrin, leader of the Trincheira Bacajá indigenous land (TI) in the municipalities of Senador José Porfírio, São Félix do Xingu, Anapu and Altamira in Pará, was known. Beptok was diagnosed on 3 August 2020. On the 6th he was taken to the Hospital Regional de Altamira and, two days later, to the ICU of the Hospital Regional Público da Transamazônica. He died on 31 August, after 26 days in hospital.

Beptok Xikrin, chief Jaguar, died from Covid after 26 days in hospital

Photo: Rafael Salazar / Poltrona Filmes

“Our great chief Beptok was the sole chief when this was a single village, the Bacajá village. In the 1980s, there was an invasion and the chief mobilized us to expel the intruders. Today, they are grabbing this same area, there is another invasion. We are organizing to expel them, just as he did. Within the indigenous land, we now have twenty villages. It is difficult for us to organize to keep a check on our land”, says Bebere Xikrin, chief of Kenkro village and president of the Associação Bebô Xikrin do Bacajá.

Recent incursions of land grabbers have caused a massive increase in deforestation within the Trincheira Bacajá indigenous land, with a loss of more than 70 km2 between 2018 and 2020, according to data from Prodes/Inpe. During this period, the indigenous land of the Xikrin was the fourth most deforested in the Amazon. In September last year, it was among the indigenous lands in Pará that burned the most. According to chief Bebere, about four or five kilometres from Kenkro village, in the direction of Vila Sudoeste, there are areas invaded by pasture and cattle.

As if the impacts of the Belo Monte hydroelectric project, land grabbing, fire, and illegal deforestation were not enough, the pandemic came. Beptok, chief Jaguar, was the first indigenous person to die of Covid in the middle Xingu, at the age of 78. The leader of the Xikrin people is buried in Pytakô village. The choking fronts reached not just Trincheira Bacajá, but the whole mosaic of protected areas of the Xingu, threatening its socio-biodiversity and environmental connectivity.

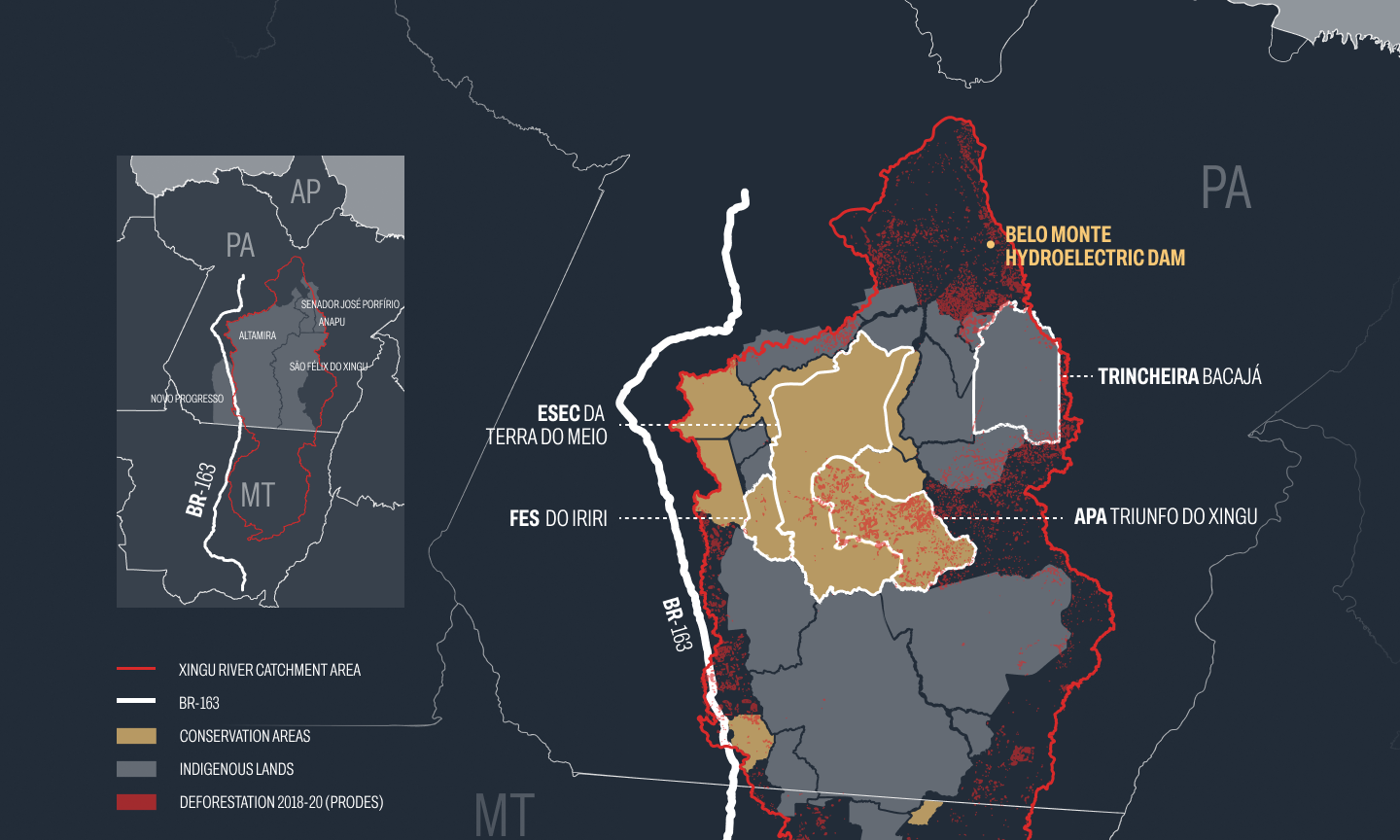

Cattle, land grabbing and clearing in the Xingu

“The most worrying region is that between São Félix and Novo Progresso. On the one hand, there is a very wide deforestation front that has been destroying the Triunfo do Xingu Environmental Protection Area (APA). This front has several branches that have already entered the Terra do Meio Ecological Station (ESEC), in the direction of the Iriri River. On the other hand, the pressure comes from the BR-163 highway, with several clearings and land grabs within the Iriri State Forest (FES), heading towards the other front”, explains Ricardo Abad, geoprocessing analyst at the Xingu+ Network.

Xingu Protected Areas Mosaic

Source: catchment and protected areas: Xingu+ Network; deforestation: Prodes/Inpe

The Triunfo do Xingu Environmental Protection Area (APA), which is partly in São Félix do Xingu and partly in Altamira, is constantly at the top of the list of deforestation and heat sources in state conservation areas in the Amazon. According to Prodes calculations, this protected area has lost more than 1.8 million km2 of forest over the last five years. In the case of fire, the main source is livestock. According to IBGE, São Félix is the municipality with the largest cattle herd in the country. Although the ESEC da Terra do Meio and the FES do Iriri are much better conserved, they are already on a path towards destruction.

In August 2020, the System for Radar Indication of Deforestation in the Xingu Basin (Sirad X) team, of the Xingu+ Network, denounced the existence of invasions and illegal logging and mining activities in the FES do Iriri to the Pará government and to the state public prosecution service in Altamira. Analysis of records from the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) carried out by Sirad X identified areas where land was being parcelled up and sold in the conservation area, with more than one group grabbing the same area.

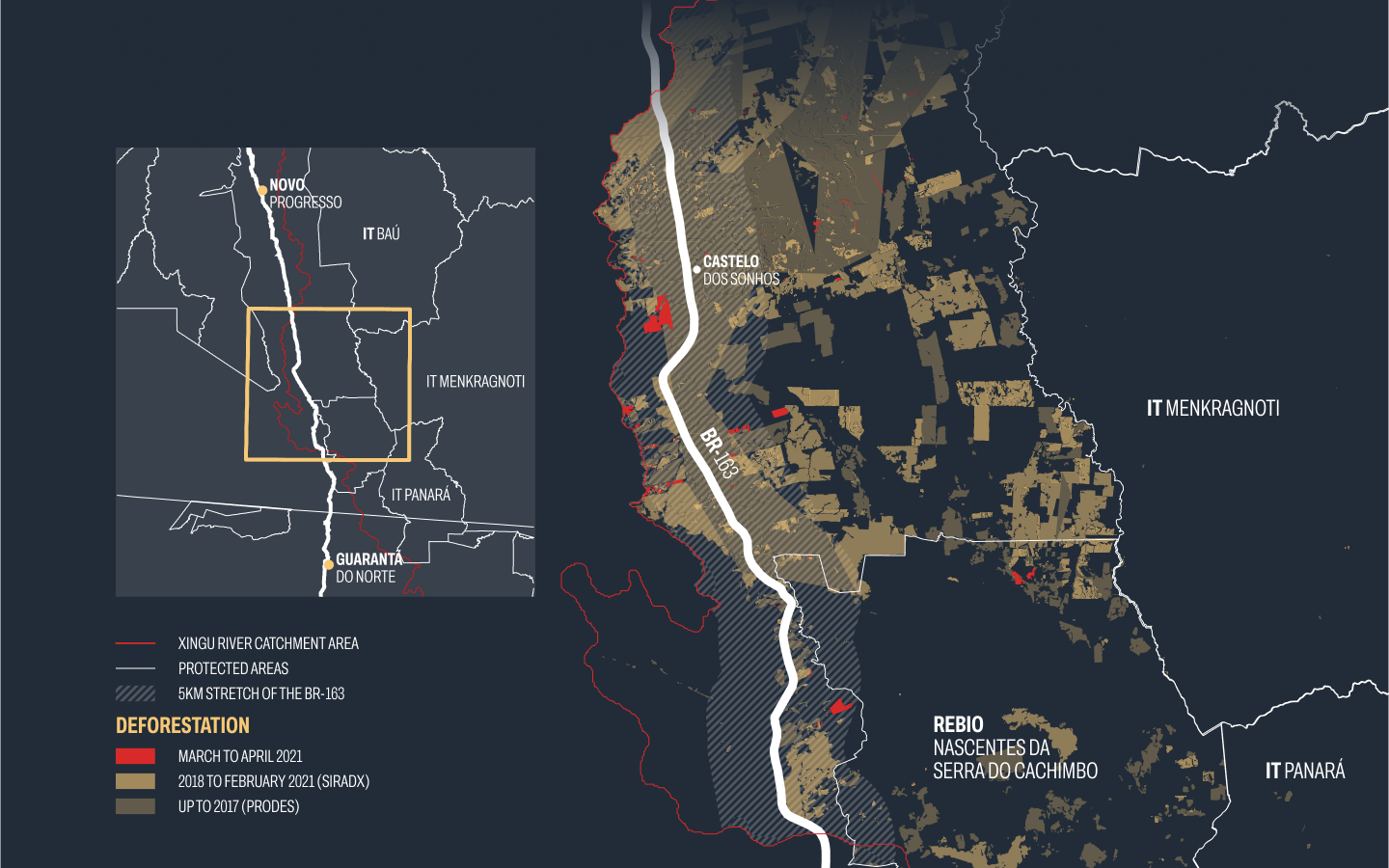

The red line shows the fewer than 50km needed to connect the illegal forest roads opened up in recent years inside protected areas on the Novo Progresso side (left) and São Felix do Xingu (right) in the Xingu Corridor. Source: Rede Xingu+, Sirad X.

“Today, there are fewer than 50 kilometres needed to complete a direct connection between the Novo Progresso side of the BR-163 highway and the other side in São Félix do Xingu. With this connection, you practically cut the Xingu in half”, warns Abad. This link, traversing three municipalities on the list of those most vulnerable – including Altamira and São Félix, the champion burners from July to October last year – would represent incalculable damage to biological diversity. The forest will be increasingly squeezed by a network of degradation.

Fire and gold on the soybean route

Novo Progresso, through which the BR-163 passes, is the municipality of the ‘day of fire’, the day of coordinated action by farmers involving simultaneous widespread burning of vegetation, which took place in August 2019. It is also the location of the National Forest (Flona) of Jamanxim, the federal conservation area with the most fires in last year’s burning season and the one with the greatest increase in area deforested, almost 300 km2 between 2018 and 2020, according to Prodes.

In August 2020, the Kayapó blocked the BR-163 to demand the renewal of the indigenous component of the Basic Environmental Project (PBA) of the highway, public consultation, and recognition of the impacts of the Ferrogrão railway, as well as health care, given the precarious state of the Novo Progresso municipal hospital and the indigenous health centre. By then, four Kayapó elders had already died from Covid-19. While the protest took place, a large cloud of smoke covered the road. The indigenous component of the PBA has not so far been renewed.

In the midst of the smoke, Kayapó indigenous people protest on the BR-163 highway, August 2020

Photo: Lucas Landau / Instituto Kabu

In July, the federal government auctioned the BR-163 concession between Sinop, Mato Grosso, and Miritituba, in Pará, for a period of 10 years. There are signs of degradation along this commodity export corridor. In the initial stretch of the BR-163 to Castelo dos Sonhos, a district of Altamira, Sirad X monitoring identified a 359% increase in the area deforested, comparing the first four months of 2021 with the same period last year.

BR-163: 359% increase in deforested area

Fonte: Rede Xingu+

“As roads trace over the land the way in which the frontier will fluctuate, so the state overlays the already existing connections between peoples and socio-biodiversity”, explains Marcela Vecchione, researcher, and professor of the Programme for Sustainable Development of the Humid Tropics of the Centre for Advanced Amazon Studies at the Federal University of Pará. The idea of a frontier refers to areas of native forest where deforestation is advancing.

In addition to the highway, the infrastructure package planned to serve agribusiness can count on the imminent authorization to build the EF-170 ‘Ferrogrão’ railway – even without the mandatory prior consultation with indigenous peoples – and the complex of private cargo ports in the Miritituba district of Itaituba, where multinationals such as Bunge/Unitapajós and Cargill operate, and which continues to grow.

In this region, alongside the pressure arising from the logistical infrastructure for exporting soy, another activity has been causing conflicts: the illegal exploitation of gold. A public civil action by the federal public prosecutor’s office (MPF) seeks to suspend mining permits in Itaituba, Jacareacanga and Novo Progresso. The aim is to stop the laundering of gold, a practice of illegal mining that disguises the origin of the ore. A study by the Environmental Services Management Laboratory of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, in collaboration with the MPF, identified more than 4,000 hectares of deforestation within the Kayapó and Munduruku indigenous lands linked to mining in 2019 and 2020.

Violence between lumber and cattle

Sebastião, Francisco, Valmir, Aldo, Izaul, Fábio, Edson, Ezequias, Samuel. These nine squatters from the Taquaruçu do Norte settlement project in Colniza, Mato Grosso, were tortured and murdered in April 2017. Four hooded men carried out the slaughter with bullets and machete blows. The person accused of masterminding the crime, Valdelir João de Souza, was a logging entrepreneur. According to Repórter Brasil, last year he was still on the run and involved in cattle rustling in Rondônia.

Amidst murders and land conflicts, Colniza heads the list for deforestation and heat sources in the Amazon portion of Mato Grosso. Between 2016 and 2020, Prodes notes, more than a thousand km2 of forest were lost. Adailton Luz, a major in the fire department of Juína, coordinates firefighting in Colniza and eight other municipalities in the region. “Fires here are mostly to clear pasture; and also to exploit timber. Colniza practically depends on the logging sector”, says the major.

On the border between Rondônia and Amazonas, more fire and tension. On one side, Porto Velho, the only entry on the list of the most vulnerable municipalities that is a state capital. On the other, Lábrea. Grey skies are routine in Porto Velho. Both for the 2020 fire season and for deforestation over the last five years, it ranks behind only Altamira and São Félix do Xingu. The city has the fourth largest cattle herd in the country, according to the IBGE, and functions as one of the biggest timber markets, due to its strategic position with exit routes along the Madeira River and the BR-364, a highway that crosses the country from São Paulo to the border of Acre with Peru.

“Recently, the Federal Police started to carry out more frequent operations. It is easier to inspect and sequester cargo on the waterway, because it moves slowly and is transported in large volumes. So, Porto Velho abandoned its port and focused transport of production along the highway. This is what the documents of origin tell us about legal wood. We assume that the same happens with the transport of illegal wood”, analyses Pablo Galeão, coordinator of Terra Lab, the geoprocessing centre of the International Education Institute of Brazil (IEB).

The arc of deforestation advances and suffocates

One of the crime hotspots on the BR-364 highway is Ponta do Abunã, which lies on Porto Velho’s triple border with Lábrea, Acrelândia in Acre, and Bolivia. It was here in 2017 that Manoel Quintino Kaxarari, an indigenous leader, was murdered by gunmen. Loggers from the region invade Amazonas and Acre to steal the felled trees. Deforestation, land grabbing and fear are also advancing southwards from Lábrea. In April 2019, squatter Nemes Machado de Oliveira was executed on the São Domingos rubber estate.

municipalities in the south of Amazonas end up having an umbilical relationship with neighbouring states. Then the arc of deforestation arrives, together with processes of substitution of extractive production by agricultural production, of expropriation of the lands of traditional peoples and communities.

pablo galeão

Coordinator, Terra Lab, International Education Institute of Brazil (IEB)

“Since the capital Manaus is a long way away, municipalities in the south of Amazonas end up having an umbilical relationship with neighbouring states. Then the arc of deforestation arrives, together with processes of substitution of extractive production by agricultural production, of expropriation of the lands of traditional peoples and communities. When all these problems come together, they discover that the state is very uncoordinated, it can’t exercise control”, Galeão concludes.

Lábrea is the champion municipality for deforestation in Amazonas. According to Prodes, between 2016 and 2020 it saw almost 1,700 km2 of forest felled. It was also the municipality that saw the most burning between July and October last year. The promise of improvements to the BR-319 highway, connecting Porto Velho to Manaus will increase the destruction. “If the paving of the BR-319 goes ahead, it will be a disaster. It is the site of one of the last and largest protected area mosaics in the world; protected by indigenous and riverine peoples who are being increasingly driven out by this process of degradation”, argues Marcela Vecchione.

The consequences show up in people’s health. “The peak of admissions for Covid here was in August, September. During this dry season, some things get a lot worse. There is the issue of fires, smoke in the region. This ends up being a contributing factor to respiratory syndromes. Every year at this time, we have an increase in cases of asthma, bronchitis, hospitalizations of children due to the climatic situation”, reveals Gabriela Luz, nursing manager of the Hospital Regional de Lábrea.

Gado próximo à queimada em lábrea, agosto de 2020

Foto: Christian Braga / Greenpeace

From environmental racism to planetary impact

Air pollution from burning forest biomass kills the Amazon in many ways. For those who live in the region maintaining their nature-based way of life, environmental health and human health are interlinked. In an August 2020 report, the Institute for Health Policy Studies (IEPS), the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) and Human Rights Watch found that, in the previous year, there had been 2,195 hospital admissions in the region for respiratory diseases attributable to fires associated with deforestation.

Another study, carried out by the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) and published at the same time shows that the high concentration of PM 2.5 during the peak of the fires in 2019 coincided with a 25% increase in hospitalization for respiratory problems of indigenous people aged 50 or more. The impacts of clearing forest, contaminated water, and polluted air immediately impact the peoples of the Amazon. For Vecchione, we need to think about the connections that cause the vulnerabilities of those municipalities that appear on the InfoAmazonia list.

There is a territorial connection, arising from the contiguities themselves, of how the dynamics between the legal and the illegal play out, between areas of native forest and consolidated areas, so as to decriminalize criminal occupation activities.

marcela vecchione

Researcher, Centre for Advanced Amazon Studies at the Federal University of Pará

“There is a territorial connection, arising from the contiguities themselves, of how the dynamics between the legal and the illegal play out, between areas of native forest and consolidated areas, so as to decriminalize criminal occupation activities. Precisely for this reason, there is a legal connection involving legislative and executive agendas, such that the contours of protection and demarcation processes can be changed, excluding people from participation, from the possibility of recognition of their traditional forms of land occupation. There is also an historical connection, to understand trajectories of settlement and how these vary in the Amazon from one place to another over time, transforming territories for exploitation, for the agro-mineral exporting sector. All this, and the fact that health conditions are weakened as a result of these processes, is environmental racism”, explains the UFPA researcher.

Albeit unevenly, the effects of destruction, including the high concentration of particulate matter in the air, travel and have repercussions far beyond the region. “The impacts are not restricted to local populations. They may be the ones who first feel the problem, but the degradation is so great that it has an impact on Brazil. So much so that, on the notorious ‘Day of Fire’, at 3pm it turned into night in São Paulo. The Amazon provides services on a scale that goes far beyond the northern region itself. These are planetary biophysical processes that impact Brazil and the planet”, recalls Antonio Oviedo, from ISA.

This article is part of “Breathing Smoke”, an InfoAmazonia special project undertaken with the support of the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships and the Big Local News programme of Stanford University.