The smoke from the fires and Covid sweeps from southern Amazonas to Acre

Fire in deforested area, municipality of Lábrea, southern Amazonas state, August 2020

Photo: Christian Braga / Greenpeace

“I lost my brother and sister in the space of three months last year. This is an illness I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy”. The frank and painful account of nursing assistant Regina Célia Diogo, 53, is one of the portraits of the unexpected link between fires and the increase in serious Covid-19 cases in southern Amazonas state.

An exclusive analysis by InfoAmazonia shows that municipalities like Humaitá, where Regina worked on the front line throughout the pandemic transporting seriously ill patients, is part of a critical area where residents’ respiratory problems tend to worsen as a result of the particulate matter released into the atmosphere after forests are burnt. It is a familiar scenario to those living in the region. However, last year the arrival of the new coronavirus brought an even more dramatic dimension to a region used to living in the face of both environmental and health crises.

Air pollution and increase in Covid hospitalization between July and October 2020

On the map, hover the mouse over the circles for data on particulate matter and hospitalizations for Covid and SARS in municipalities of the Brazilian Legal Amazon region.

The process that causes the forest to burn in southern Amazonas and affects the health of Amazonians is linked to what also occurs in the states of Acre, Rondônia and Mato Grosso, according to Sonaira Silva, researcher at the Environmental Applied Geoprocessing Laboratory (LabGAMA) of the Federal University of Acre (UFAC), and scientific consultant to the InfoAmazonia project. “It is the expansion of the arc of deforestation. The large numbers of fires in the past year are directly linked to livestock production and land speculation. The question of the lack of governance on the part of municipal, state, and federal governments, resulting in less inspection, also forms part of this equation. People are feeling less inhibited about burning”, explains Sonaira. According to this scientist, the work of data analysis contained in the InfoAmazonia project helps to identify the size of the problem. “Now we know the scale of the impacts of fire pollution on public health”, says Sonaira.

It is the expansion of the arc of deforestation. The large numbers of fires in the past year are directly linked to livestock production and land speculation. People are feeling less inhibited about burning.

sonaira silva

Researcher, Environmental Applied Geoprocessing Laboratory (LabGAMA) of the Federal University of Acre

Regina Célia diogo

nursing assistant, 53, Humaitá, Amazonas

The daily routine of nursing assistant Regina has changed for good, and not simply because of the loss of family members. With her oxygen saturation level at 70%, when the ideal is at least 95%, Regina had to be hospitalized in a hurry in September. She was short of breath and her chest ached. She spent ten days in hospital and on several occasions, she came close to being intubated. “For the first time, I had to swap places with my patients. It was an extremely difficult and painful time, both physically and psychologically. It felt as though my lung was in my back”, Regina recalls. Her critical condition made her diabetes, one of the comorbidities most associated with the risk of Covid leading to complications, become uncontrolled. “Even with all the support from my professional colleagues who looked after me, I needed to have oxygen with me the whole time, otherwise I couldn’t have stood it.”

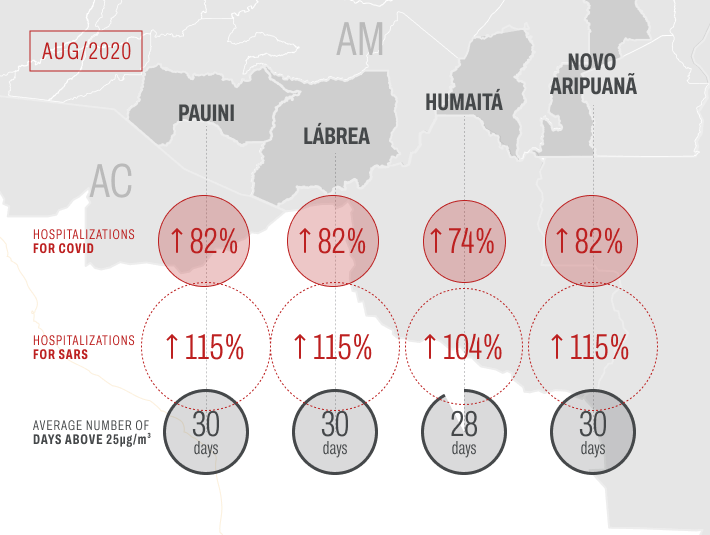

In August, a month before Regina’s fight for survival, a large area of southern Amazonas saw an explosion of Covid-19 hospitalizations. The increase in cases involving residents of not only Humaitá, but also the municipalities of Lábrea, Nova Aripuanã, Pauini, Apuí and Manicoré are all linked to the fires in the region, which show no respite during the dry season and whose sources do not necessarily lie within these municipalities themselves.

For the first time, I had to swap places with my patients. It was an extremely difficult and painful time, both physically and psychologically. It felt as though my lung was in my back.

regina célia diogo

The nursing assistant was hospitalized for ten days with breathing difficulties and chest pain

In Lábrea, Nova Aripuanã and Pauini, at the top of the list of all Amazon municipalities for August in particular, hospitalizations for confirmed Covid-19 increased 82% and those for respiratory syndromes 115%. For the entire thirty days of the month, Lábrea recorded levels of particulate matter above the 25 µg/m3 recommended by the WHO (World Health Organization). Between July and October there was a total of seventy such days. In the same period, Humaitá recorded 63 days of heavy pollution-saturated air.

In August, municipalities in southern Amazonas state were the most affected by smoke from burnings

Source: InfoAmazonia analysis

For Luiz Marques, a pulmonologist working in Manaus, there is no way to dissociate fires, pollution, Covid-19, and the lack of environmental governance. “Lung diseases are generally related to the environment in which a person lives; in other words, they are occupational diseases. People exposed for many years, for example, to smoke, burning, logging, and grazing can develop lung disease and become more susceptible to Covid-19. Therefore, as a consequence, there is a greater number of hospitalizations in the southern part of Amazonas state. It is well known that Lábrea is a municipality with weak environmental policies”, this doctor explains.

As much as residents of cities like Humaitá associate the risk of intoxication from air pollution to nearby, visible fires, this is only part of the story. In the Amazon, distant fires, which occur hundreds of kilometres away, such as those often seen alongside highways, also have a tendency to penetrate the airways of inhabitants, even those in other states. In this case, it’s an invisible enemy. Analysis by InfoAmazonia based on data from INPE (National Institute for Space Research) show that, in 2020, twelve municipalities under the direct influence of the BR-319 highway accounted for more than 40% of the heat sources recorded in Amazonas state.

The InfoAmazonia reporting team travelled from Humaitá to Porto Velho, along the BR-319, in July this year, the beginning of the new burning season. Although it is not the driest month of the year, there were fires along several parts of the route. Clouds of smoke covered the road.

Where the wind turns the corner

The synergy between local production and regional dispersion of smoke from the fires also affects Acre in full, according to Irving Foster Brown, a professor at the Federal University of Acre (UFAC). The New Yorker living in the Amazon since the 1990s argues that, in addition to the state where he lives, southern Amazonas and Rondônia are also in a corridor where you can say that the wind does in fact turn the corner. Due to the proximity of the Andes, the direction of the flow of the air masses crossing the region changes.

“The wind here in Acre comes more or less through Boca do Acre [a municipality in the interior of Amazonas, in the south of the state], and after it passes over Acre, it starts to turn southeast,” says Brown. As well as carrying the water vapour that will supply Amazon rivers, this whole movement in the atmosphere on the western side of the country also transports smoke from burnings over long distances and this increases the region’s rates of pollution.

Animation demonstrates wind circulation in Amazonia

Source: GFS / NCEP / US National Weather Service, 850 hPa altitude wind, 08/11/2020. Image: Earth

Brown explains that even municipalities with no significant records of fires can suffer from the smoke, which ends up being propelled by strong winds. Such may be the case of Pauini and other cities in southwestern Amazonas that do not have significant local fire production but spent most of the burning season with pollution levels above those recommended by the WHO, according to the InfoAmazonia analysis. “If there is a strong constant wind, it is possible for the smoke to be displaced for up to a thousand kilometres. But this does not mean that small fires in backyards don’t influence air pollution. If there’s burning, there will be smoke”, observes the UFAC researcher.

The fact that smoke projects a large amount of particulate matter into the atmosphere has consequences both immediate and over months and years, the scientist says. The most immediate implication, according to Brown, involves the emergence of acute illnesses, such as the worsening of an asthmatic condition, for example. “But there are other impacts that involve longevity. Let’s assume that a person suffered a heart attack in February of this year. Many would say that this has nothing to do with the fires. But the damage that led to the heart attack may have occurred during the smoke period in 2020, if the person is hypersensitive to air pollution.” [see box].

In this context, the arrival of the new coronavirus made the situation even more serious, admits Brown, like an already full glass that has just overflowed. “The new coronavirus can cause severe acute respiratory syndrome. If you have this predisposition to lung problems and inhale a lot of particulate matter, you will develop even more serious problems because of the virus.”

Without realizing it, at least at first, nutrition student Robson Fadell, 23, lived in the flesh what Brown theorizes. At the end of August 2020, in the middle of the fire season, the resident of Rio Branco, capital of Acre, began to feel the typical symptoms of asthma, a disease that has been with him since his early years.

Robson fadell

student, 23, Rio Branco, Acre

“During the burning season my crises become more frequent. I feel tired and I need to increase the frequency of using the pump [inhalation for bronchial dilation]. I also feel my eyes are dry. At this time of year, I always use eye drops for relief. I know that this worsening is due to the smoke because I lived in Fortaleza for a few years [where the climate is much more humid because of the Atlantic] and there my asthma didn’t get as bad as it does in Rio Branco”, recalls Fadell.

Ten days later, the symptoms had not improved, and the student noticed that his asthmatic condition was different. He woke up unable to breathe. “At the consultation, the reduction of lung capacity was already large”. The CT scan showed advanced pneumonia and the test confirmed infection by the new coronavirus. The student was immediately admitted. Two hours later, partially sedated, he needed breathing assistance. Fadell recorded a significant worsening over the next four days, with CT scans revealing increasingly compromised lungs. The doctors concluded that mechanical ventilation was no longer sufficient. He was prepared for intubation, but the next morning showed signs of improvement and the doctors changed their minds. He spent sixteen days lying on a hospital stretcher fighting for his life. Friends even held an online whip-round to defray his medical expenses.

“The period of my hospitalization played havoc with my psychological state and has affected my life forever. The whole time there was that uncertainty. I thought I was going to die; that was what was going through my mind the most”, Fadell recalls. The student has no doubt that the smoke from the fires further weakened his respiratory system, which contributed to the severe infection by the coronavirus which has already claimed around 1,800 victims in Acre.

The period of my hospitalization played havoc with my psychological state and has affected my life forever. The whole time there was that uncertainty. I thought I was going to die; that was what was going through my mind the most.

Robson fadell

Covid worsened the situation of the student who suffers from asthma

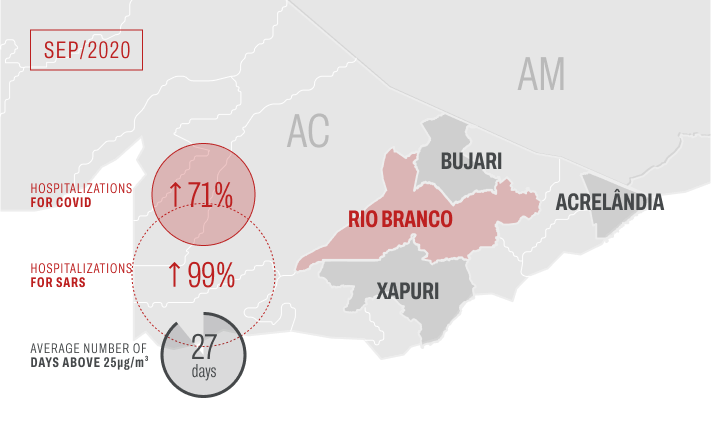

Fadell’s case illustrates the delicate moment that Rio Branco experienced during the fire season in 2020. In September, when he was hospitalized, the capital of Acre saw a 71% increase in hospitalizations for Covid-19 and 99% for severe acute respiratory syndrome, occupying first place in the state ranking. In the same month, the municipality also emerged as the most polluted in Acre, suffering 27 days with levels of particulate matter above the WHO recommendations. September was also the month with the most fires in the state.

Rio Branco was the most polluted municipality in Acre

Source: InfoAmazonia analysis

During the entire fire season, which runs from July to October, Rio Branco had an average of 13.2 days a month with harmful pollution levels, behind only Acrelândia (14.8) and Bujari (13.5) in the interior. During these four months, Acre had 22% more hospitalizations for Covid and 29% more for severe acute respiratory syndrome.

The burning period is temporary, but its effects can be long lasting. Almost a year after his Covid-19 was cured, Fadell is still living with the aftereffects of the infection aggravated by asthma, which in turn was made worse by the smoke from forest fires. His respiratory capacity, he says, has not returned to what it was before the infection. “If I talk a lot, I soon feel tired. My blood pressure has become unstable, as has my blood sugar”, he complains, already worried about the approaching peak of fires and pollution this year.

Suffocating in Rondônia

Fires linked to deforestation and masses of air similarly polluted by particulate matter moving from other regions of the Amazon placed the lungs of residents of several cities in Rondônia under pressure. Against this backdrop, when the pandemic began to grip the region during the 2020 dry season, according to the InfoAmazonia analysis, admissions for Covid rose by up to 36%.

Between July and October 2020, Rondônia had a monthly average of 15.6 days above the recommended level. This means that on half the days of every month throughout the burning season, the population of the state breathed air at levels above tolerable levels for human health. In no other Amazonian state was the situation so serious.

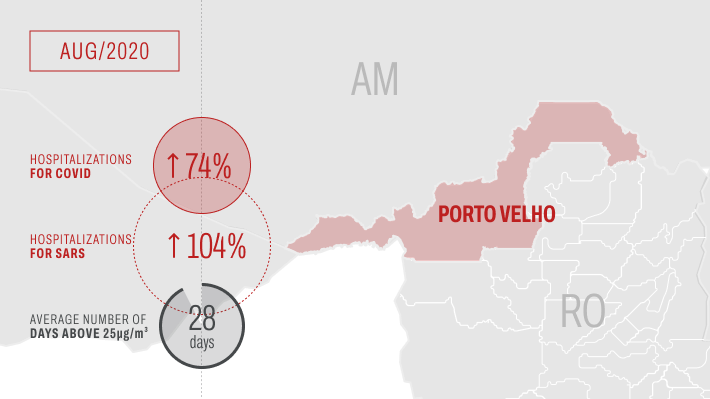

August was the month of greatest impact in Porto Velho

Source: InfoAmazonia analysis

In the capital, Porto Velho, air pollution is linked to a 45% increase in Covid-19 complications between July and October. In August alone, the month with the highest impact on the city, there were 74% more admissions for Covid and 104% for SARS in general. Out of all Amazonian municipalities, the city ranked seventh for the greatest impact of smoke on increased hospitalizations.

The impact of the saturated air that hovered over the cities of Rondônia may be behind stories such as that of the Costa family, who lived in the Castanheiras neighbourhood in Porto Velho, which had second highest level of confirmed cases in the entire state, according to a survey by Portal Covid, by the state health department (Sesau).

The Costa family

Castanheiras neighbourhood, Porto Velho, Rondônia

In August, Dannys, as Daniela de Souza Costa was known, lost her life to the virus at the age of 38. “She had no comorbidities. She went to the hospital with suspected Covid-19, and once the test proved positive the doctor admitted her. She had already lost 50% of her lung capacity. She stayed on the ward for the first four days and then was taken to the ICU”, says her sister, journalist Daiana de Souza Costa. The Porto Velho resident died on 12 August 2020, 28 days after entering the ICU of the 9 de Julho Hospital. She left a husband and a five-year-old daughter. The burning season was still in its infancy, but two months earlier, in June, the family had already been heavily impacted by the pandemic.

“I saw the pandemic much closer than I wanted. Before my sister, who was only 38, I lost my father in June. These were two losses very close together. Today, of my family, only my brother and I are left”, remembers Daiana, who lives in the district of Nova Mutum Paraná, about a hundred kilometres from Porto Velho.

I saw the pandemic much closer than I wanted. Before my sister, who was only 38, I lost my father in June. These were two losses very close together. Today, of my family, only my brother and I are left.

daiana de souza costa

journalist whose brother was hospitalised and whose father and sister died of Covid

Danilo, her brother, lived with his father in the capital and experienced the symptoms of Covid-19 first. “For part of the time, he and my father were infected in the same house. My father took care of my brother, but shortly after he started to have shortness of breath and problems breathing. He had diabetes and kidney problems,” says Daiana. Danilo had pneumonia and had lost 50% of his lung capacity. “My father and I took care of each other”, recalls the accountant. “When he became really ill, I had already got better. He was then taken to the first aid clinic (UPA), in the south zone of Porto Velho, where he was hospitalized.”

According to Daiana, Áureo Costa, her father, arrived at the hospital with more than 60% of his lungs affected and died waiting for a place in the ICU. “He was hospitalized one day and died practically the next, on a UPA stretcher waiting for a space. He needed a bed where he could undergo haemodialysis, but all the places were full”, the journalist laments.

Where Áureo was left patients were not given food, says Danilo. “It was up to the family to take all the meals. On the day my father died, I took him lunch, a bean broth with orange juice, and I put the food into his mouth. That lunch was our last moment together”.

Pandemic and pollution continue waiting to pounce in Humaitá

“I died with her. I always say that, because it’s not easy to go on living in this house, everything reminds me of her. She was the one who woke me up in the morning, made coffee, played with me… She is this house.”

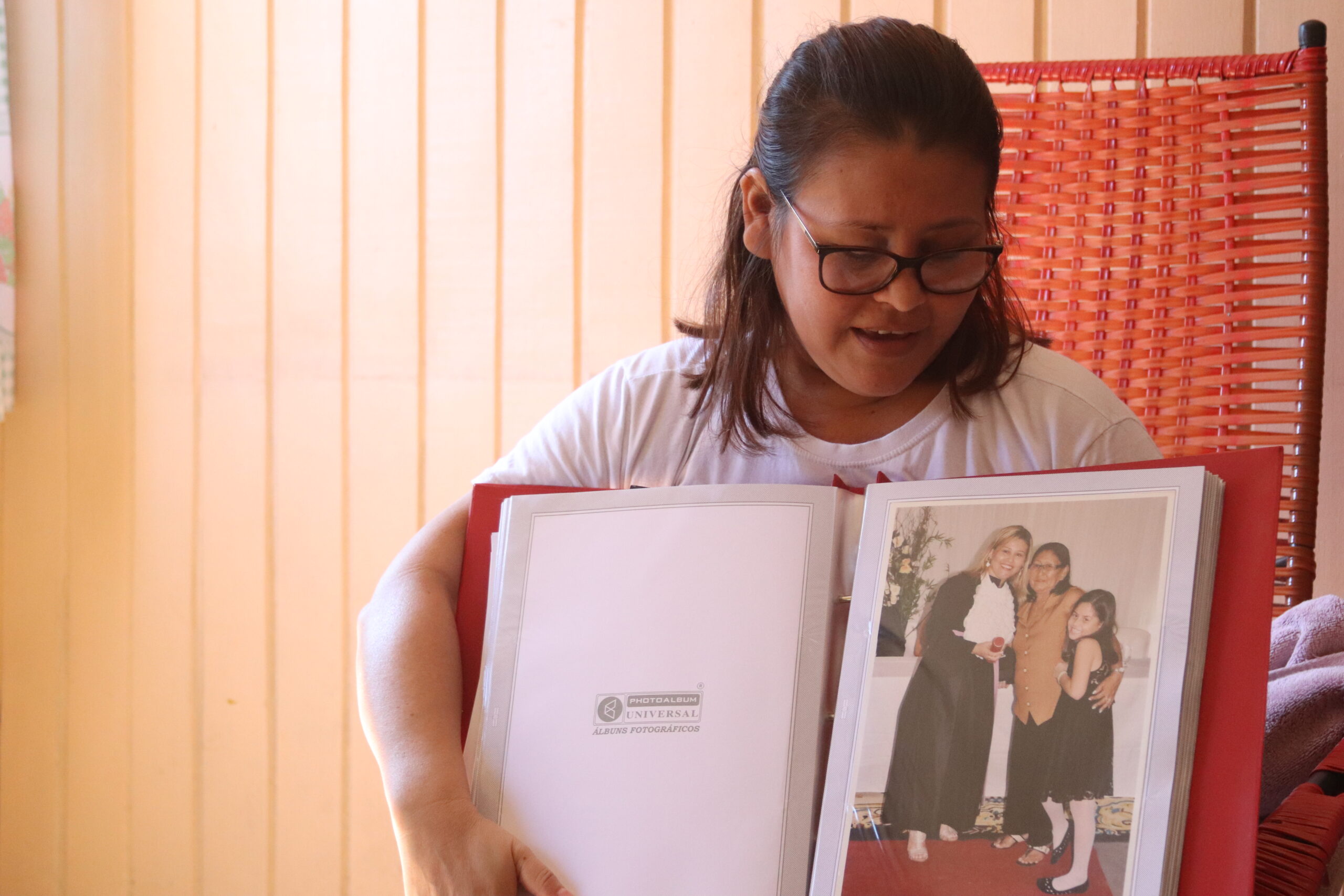

Márcia and her mother were hospitalized with Covid-19, but only she survived

There are those who believe that the pandemic is over, but for those who have gone through the pain of loss, it is still very present. Infected with the virus, manicurist Márcia Gude, 39, was admitted to hospital in early 2021 at the same time as her mother, but in different hospitals. Only she survived.

As Márcia’s mother suffered from lung problems because of complications from past tuberculosis, every time the smoke from the fires arrived, she asked her mother to put on a mask. Contrary to popular belief throughout the city, it is not just when fire and smoke are visible that the risk of breathing particulate matter increases. Sometimes you don’t see the fire, but pollution is present [see article 1 of this series]. Until they need medical attention for respiratory problems, many residents of southern Amazonas do not realize the toxic impacts of air pollution.

The two got through the burning cycle unscathed by the virus, but at the start of this year they were infected. The manicurist developed pneumonia and Marcia was transferred to the same ward where her mother was already hospitalized. But they couldn’t even see each other. With the help of the nurses, their only form of communication was by photos on their cell phones that the nursing staff took during their breaks.

“We made a promise to each other before it all happened. She would stay with me, and I would stay with her. When I got worse because of the pneumonia, I said I didn’t want to be transferred to Porto Velho. I wanted to stay in Humaitá, with her”, recalls Márcia, showing a photo of her mother.

The acute situation caused by the pandemic last year, together with the chronic situation characterized by constant annual fires, as happened last year, are still the case in southern Amazonas and the tendency is for them to happen again this year, showing that the problem is far from over.

This article is part of Inhaling Smoke, an InfoAmazonia special project undertaken with the support of the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships and the Big Local News program of Stanford University.