Survey led by the INPE and Fiocruz, in partnership with InfoAmazonia, was conducted based on satellite images of indigenous land and analyzes the impact of territorial change on rivers and communities, including mining, degradation and deforestation. Over 62% of the Yanomami population live in areas under the influence of invaders.

A new survey reveals the alarming distribution of damage caused by invasions and illegal mining in the rivers and villages of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in Roraima. The results show that 59% of inhabited rivers, meaning those that are home to nearby communities, show strong signs of contamination.

The analysis was conducted by the Geo-Yanomami Working Group, comprised of researchers from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), Veiga de Almeida University (UVA), the University of Brasília (UnB), the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM) and others in exclusive partnership with InfoAmazonia. Techniques of geoprocessing: According to the Institute of Forest Research and Studies, geoprocessing refers to the various techniques used in the collection, storage, processing, analysis and representation of data with spatial expression, in other words those that are possible to be referenced geographically (georeferenced). were employed and remote sensing: Remote sensing is the technique of obtaining information about an object, area or phenomenon located on Earth, without having physical contact with it., which allow continuous and remote monitoring – the methodology does not include the collection of samples from rivers or people in loco. The scientists chose to use the limit of the federal government’s actions in indigenous healthcare, the Special Indigenous Sanitary District (DSEI), to determine which areas have been most impacted by the activity of illegal miners since 2015.

Maurício Ye’kwana, director of the Hutukara Yanomami Association, had access to the survey and states that, although there were invasions by illegal miners before Covid-19, it was during the pandemic and under the Bolsonaro administration that the situation intensified: “The inspections stopped and illegal mining increased dramatically.” He goes on to explain the important role that experts play in understanding the real situation in the territory:

“For indigenous people, a river whose color has gone muddy is polluted. It’s already contaminated. We have no way to measure whether there’s mercury, whether there’s been a fuel spill. We don’t know. That’s why we ask the specialists, especially Fiocruz, to conduct their analysis. But, looking at the whole thing, we know it’s contaminated.”

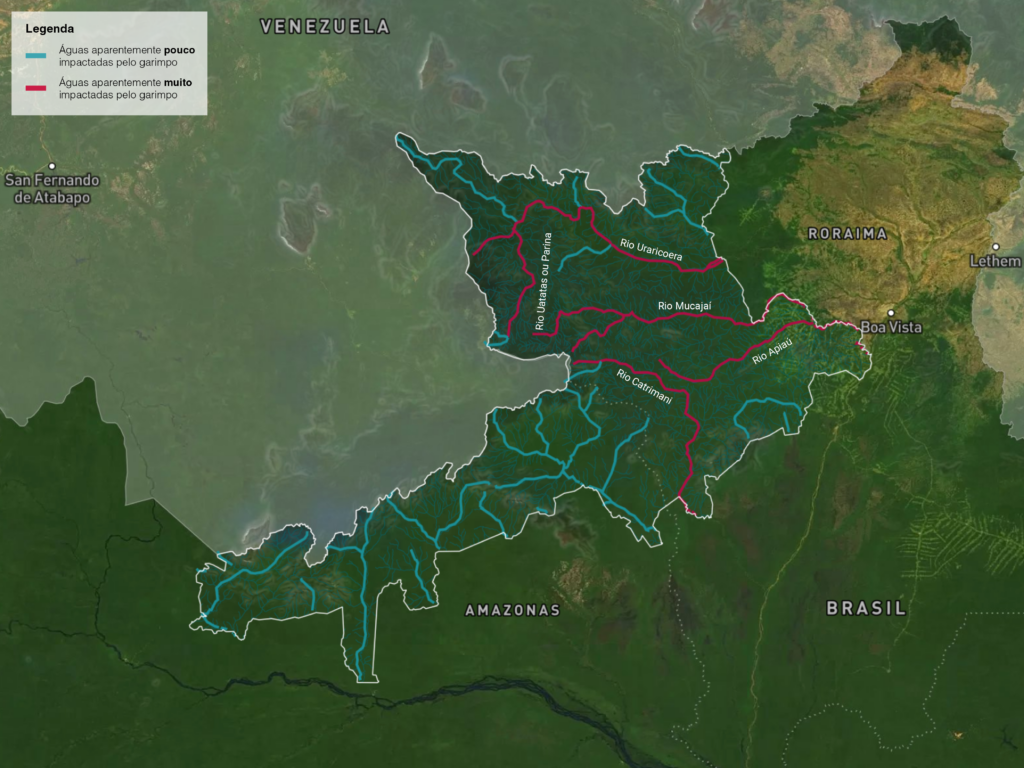

Illegal mining in inhabited rivers

The researchers looked at three factors that are very relevant to indigenous people’s survival: the rivers, the territory and the villages. They took into account the hydrological network, which covers about 25,000 kilometers within the Special Indigenous Sanitary District (DSEI). Of these rivers, approximately 1,900 kilometers have indigenous communities within a one-kilometer distance of their banks.

As such, it was possible to understand which rivers were inhabited and then begin to understand the factors of interaction with the reality of the indigenous people. The initial question was: what is the territory like in the vicinity of the inhabited rivers and villages?

To respond, the authors relied on data from Deter: A tool from the federal government that generates quick alerts of evidence of alteration in the forest cover in the Amazon and the Cerrado., a system of the INPE that conducts a quick survey with alerts of evidence of alteration in the forest cover. They identified which rivers had an area of exposure to the alerts and thus came to the following data: 59% of the rivers usually inhabited by the Yanomami are currently under the effect of mining and invasions, with a high probability of mercury contamination, impacting biodiversity and Yanomami life.

Diego Xavier, a doctor of public health at Fiocruz and one of those responsible for the study, says, “this is a conservative estimate.” In addition to possible inaccuracies in the data and a lack of specific studies on the ethnicities that make up the people and the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, he points out another factor: indigenous people circulate in the territory a lot in order to complete hunting, fishing and agriculture activities, as well as inter-community visits and rituals. In other words, the 1,900 kilometers of inhabited rivers analyzed consider only the set location of the villages, but the problem is probably even bigger, since with circulation throughout the territory, the indigenous interact with other rivers potentially affected by illegal miners and invaders.

Nathália Saldanha, an anthropologist and PhD in Healthcare Information and Communication at Fiocruz, explains that “the basis of life of these indigenous populations is in the forest and rivers, influencing their relationship with the space, food, community and between communities. Therefore, the river and the forest become central elements in the indigenous social organization. They engage in a pendulous movement of approaching and distancing themselves from the permanent contact points and, as such, make use of second residences, where they go to the river and back to the interior of the forests,” he explains.

Saldanha emphasizes that this displacement throughout the territory between rivers, villages and denser forests takes place “in search of hunting, fishing and other foods that are part of their nutritional base. Whenever there is a presence of invaders and miners in the area, the indigenous populations flee and try to get as far away as possible.”

Carlo Zacquini, a Catholic missionary from the Consolata Missionary Institute, dedicated decades to the struggle for Yanomami rights during the military dictatorship and experienced firsthand the catastrophe that was the mining invasion in the 1980s. “The Yanomami have nowhere to run. They have to eat what’s there. With the illegal prospecting, the amount of fish in the area has decreased dramatically. This is not so much due to the mercury, but more because of the mud that’s injected into the river, with these bombs that break up the lands in the ravines, and this removes the oxygen. The Yanomami say that the fish float by on the water’s surface.”

The Yanomami have nowhere to run. They have to eat what’s there. With the illegal prospecting, the amount of fish in the area has decreased dramatically. This is not so much due to the mercury, but more because of the mud that’s injected into the river, with these bombs that break up the lands in the ravines, and this removes the oxygen. The Yanomami say that the fish float by on the water’s surface.

Carlo Zacquini, a Catholic missionary from the Consolata Missionary Institute

The scale of the destruction is so great that Zacquini says he finds it difficult to compare what is currently happening in Yanomami territory with what he witnessed 40 years ago. According to him: “We keep talking about prospectors, but I think that’s wrong, because there are big companies, expensive machines and the number of planes and helicopters that circulate there is extraordinary. Even after the destruction of dozens of planes and helicopters, the illegal mining continues. ”

Collective life at risk

Though the conclusion that “over half of the inhabited rivers are affected by illegal mining and invaders” is alarming in itself, the analysis was complemented by considering the “living areas” in each indigenous community in the Yanomami DSEI — the researchers focused on calculating the percentage of villages at risk and determining the proportion of the population subjected to the influence of territorial problems.

As such, an area of five kilometers (direct living area) was established around each community, taking into account the Yanomami’s locales of circulation. At the same time, another area of up to one kilometer was also created around the sites identified via Deter as having had changes in forest cover, including mining, deforestation and burning.

The overlap between living areas and problems related to invaders showed that about 62% of the Yanomami population lives in risk areas.

The significance of these statistics for Yanomami collective life “is the progressive extermination of this people,” says Nathália Saldanha. The anthropologist explains that river contamination affects all aspects of indigenous life: nutrition, sanitation, demographics, social and even cosmological aspects. “The presence of heavy machinery, dredges, tractors and other machines used for illegal mining drives away game animals, in addition to polluting the land and rivers. These are people who live off of hunting,” she says.

The presence of heavy machinery, dredges, tractors and other machines used for illegal mining drives away game animals, in addition to polluting the land and rivers. These are people who live off of hunting.

Nathália Saldanha, anthropologist

According to Maurício Ye’kwana, “The community area has been degraded, the igarapé was destroyed, hunting has been destroyed, and the Yanomami are starting to ask the prospectors for food. The dispersion and change in the community’s coexistence has begun: drugs, alcoholic beverages are coming in.”

The indigenous leader explains that, due to the lack of food in the communities most affected by mining, they’re forced to migrate: “They go to other regions, which generates conflict. They have nowhere else to hunt, so they look for other sources of livelihood in different areas. ” Ye’kwana also highlights that the distribution of weapons by miners is making these conflicts more violent: “The other communities feel they’re being robbed, but these people are just trying to meet their needs.”

“There were no conflicts within the communities. Then the prospectors come in and say that FUNAI is not a friend, but that the prospectors are friends. They promise clothes, ammunition, medicine. And this is changing indigenous people’s thinking,” he adds.

The community area has been degraded, the igarapé was destroyed, hunting has been destroyed, and the Yanomami are starting to ask the prospectors for food.

Maurício Ye’kwana, director of the Hutukara Yanomami Association

The most recent report by the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) found that indigenous people represent 38% of murder victims in rural areas of Brazil in 2022. The CPT highlights the concentration of violence against the Yanomami population: “In 2022, of the 113 records obtained, 103 were in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, and of these, 91 were children, representing 80.5% of the cases.”

In addition to the violence, there are many effects on health. Along with the cases of severe malnutrition, there has been an explosion of malaria due to standing pools of water produced by mining itself, parasites and mercury contamination. “The mercury remains in that water and, in addition to the rivers, it contaminates food and fish,” explains Saldanha. The presence of prospectors has also fueled a rise in sexual violence against indigenous women, rape and outbreaks of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs).

Landing strips and the mining invasion

In January of this year, the federal government launched a series of actions to combat mining within the Yanomami Indigenous Territories. At the time, the Ministry of Health stated that approximately 570 indigenous children lost their lives due to mercury contamination, malnutrition and starvation. In response, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) traveled to Roraima and determined the definitive removal of the miners.

Despite this, Maurício Ye’kwana warns of the possibility of more violence, because, according to him, the ones who are resisting are heavily armed, organized criminal factions that are confronting the police forces: “Criminal factions have taken over the mining. They’ve started charging the propsectors and even the indigenous people to be able to pass. North of the Uaicás community, on the Uraricoera River. The police installed a base, a steel chain, but the miners pass by and cut the chain. There aren’t enough police officers and the criminal factions know that the police forces don’t have the power to stop them. “

Criminal factions have taken over the mining. They’ve started charging the propsectors and even the indigenous people to be able to pass. North of the Uaicás community, on the Uraricoera River. The police installed a base, a steel chain, but the miners pass by and cut the chain.

Maurício Ye’kwana, director of the Hutukara Yanomami Association

According to an estimate by the Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY), before the actions of the federal government, there were about 20,000 prospectors operating illegally within the territory. Diego Xavier, of Fiocruz, says that one of the central elements for understanding this degradation of the Yanomami territory is the facilitation of geographical access. “It has increased dramatically. The miners took the landing strips that were already there and built new ones. And the inspections didn’t stop them. They began invading the space where indigenous people lived and expelling them. ”

Maurício Ye’kwana details this lack of control over landing strips in indigenous territory. “In the regions where the airstrips were taken over, mainly by prospectors, this was due to the threat against the health workers present there. SESAI doesn’t offer the same things that the prospectors do,” he said, referring to the prospectors’ distribution of goods, clothing and food.

“Those who are more heavily armed, more powerful and have more force are the ones who have taken control of the landing strips and started using them. This is what happened in the region of Homoxi, for example. There are constant flights, one after the other.”

The survey of the Geo-Yanomami Working Group manually identified, one by one, the landing strips, using as reference satellite images taken by the Planet system in December, 2022. Their characteristics include a straight-line format and exposed soil, and some include thresholds and support structures.

Jefferson Santos, who holds a PhD in Epidemiology and Public Health from Fiocruz, and coordinator of the Laboratory of Geographical Intelligence in Environment and Health (Ligas) at Veiga de Almeida University, is responsible for this part of the analysis and mapped 188 airstrips in the territory.

Subsequently, the researcher cross-referenced the location with that of the rivers. Among the 188 airstrips, he identified 138 (73%) that have a highly impacted river nearby.

7 of 10 airstrips are nearby a heavily impacted river

Santos explains that, in the Amazon, outside the metropolitan areas, connections are made mainly via rivers and small airplanes. “Due to the illicit nature of this activity [mining], which involves large numbers of people and resources such as gold and money, the airstrips are used as an efficient means for rapid entry and the outflow of resources, individuals and values, facilitating mining operations and making inspection difficult.”

Due to the illicit nature of this activity [mining], which involves large numbers of people and resources such as gold and money, the airstrips are used as an efficient means for rapid entry and the outflow of resources, individuals and values, facilitating mining operations and making inspection difficult.

Jefferson Santos, PhD in Epidemiology and Public Health from Fiocruz and coordinator of the Laboratory of Geographical Intelligence in Environment and Health (Ligas) at Veiga de Almeida University

He contrasts the convenience that the planes offer for mining with the slowness of river transport, and points out that rivers “do not have the same capillary reach that airstrips can offer. It's relatively simple to open up an airstrip and, once established, airplanes can quickly reach practically any area. In this way, they have the potential to accelerate exploration and expand the mining activity to areas that were previously inaccessible,” the researcher adds.

Major rivers contaminated

Another, more regional part of the survey presents the extent of the impact on indigenous territory generated by the mining invasion.

Considering only rivers with a large volume of water - classified as fourth or fifth-order, to use the technical term - 63% of located Yanomami villages have an impacted river as their closest body of water. Water quality analysis was performed from visual interpretation of satellite images taken by the Planet system and the company Esri, with an assessment of color change in 2015 and 2022.

63% of villages are nearby a highly impacted river

According to Jefferson Santos, these are rivers "with high amounts of particulate matter, generating changes in color and quality parameters, such as oxygenation." Based on the assessment of color change, it was possible to evaluate the impact mining had on contamination by particulate matter in the main bodies of water in Yanomami land.

This visual analysis found that most of the villages are close to highly impacted rivers and, especially, large ones. “It is difficult for a village to be located far from a river of higher order. Goods arrive via these larger rivers,” explains Santos.

One of these large, heavily impacted rivers is the Mucajaí, which crosses the central and eastern region of the Yanomami territory. The consequences of the mining activity are so severe that the river's course has been altered--the object of a disturbing celebration by miners shown in a video that has circulated on social media.

According to Diego Xavier, an action as drastic as the one seen in the video, which definitively changes a watercourse, can “even lead to the death of the river.” The researcher explains: “The mercury deposit seeps into underground aquifers. There is also loss of biodiversity and a surrounding microecosystem: some animals, which had the regulated environment, are affected by the diversion of this river, the loss of water volume and siltation.” An impact is generated for the entire basin, since the Mucaja is itself “an important tributary of the Rio Branco that, in turn, flows into the Rio Negro, which contributes to the flow of the Amazon River. In this sense, the analysis presented here most likely also presents a conservative estimate of the extent of the impacts that have occurred.”

Contamination spreads beyond indigenous land

All the rivers of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory flowing into the Rio Branco, which supplies water to Boa Vista, or the Rio Negro, which spans several indigenous territories and, in turn, sustains the city of Manaus. The effects of mercury on the health of urban populations, even if relatively distant from the areas first impacted by mining activity, have been the subject of other studies by Fiocruz which indicate contamination in cities connected in some way to rivers exploited by mining, such as Boa Vista, Roraíma and Santarém, Pará.

This report is part of the PlenaMata project, and was produced as part of the InfoAmazonia Laboratory of Geojournalism, executed with support from the Serrapilheira Institute to promote and disseminate scientific knowledge and geographic data analysis in journalism.