InfoAmazonia visited location where illegal mercury is sold along the border between Bolivia and Brazil, for illegal use by wildcat gold mining operations in Amazonia. After the Minamata Convention, Bolivia became the world’s largest mercury importer and it is estimated that half of the metal is sold as contraband to neighboring countries including Brazil, which has eliminated its legal mercury imports.

Comercial Bryan looks like a typical border town shop, with a broad selection of items for sale, ranging from traditional home furnishings and electronics to beauty supplies and clothing. Since the exchange rate is always good, Brazilians come to the municipality of Guayaramerín in Bolivian Amazonia looking for low prices. On the other side of the Mamoré River lies Guajará-Mirim, the Brazilian rubber industry boom town from the start of the 20th Century that today looks more like the set from a Wild West film. On every street corner one sees Brazilian cars filling up their tanks with gasoline brought over the border illegally in cans. Trucks, cars and pickups stop along the riverbank to load up on a little of everything that comes across the border, with no regard for the local Customs office.

The ease in crossing the border at Guajará-Mirim also oils the cogs of those needing mercury for their illegal mining operations in Brazilian Amazonia.

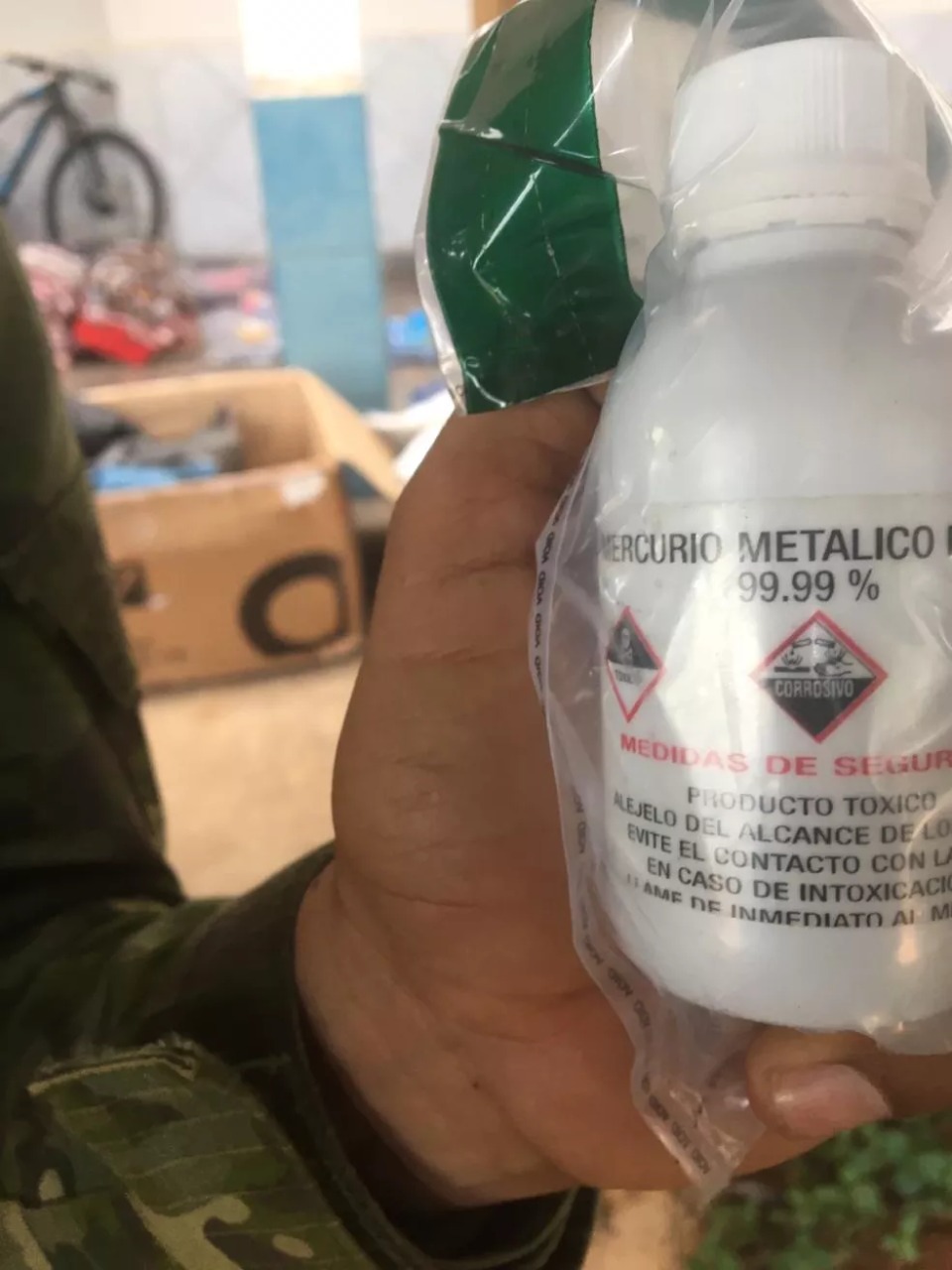

This particular item is not on display in shop windows, but bootleg mercury brought across from Bolivia can be purchased at many stores like Bryan, which itself sold over 100 kilos of mercury for around R$ 220,000 during a one-month period between August and September of this year when our reporters visited the store and were in contact with the owner and her salespeople.

Dealings of the metal arriving from the Bolivian side are also carried out at jewelers, beauty shops and in private homes—always in a discreet manner. “ I’ve been selling [mercury] on the border for eight years. Absolutely, I have the product”, one seller from Guayaramerín told us in a text message.

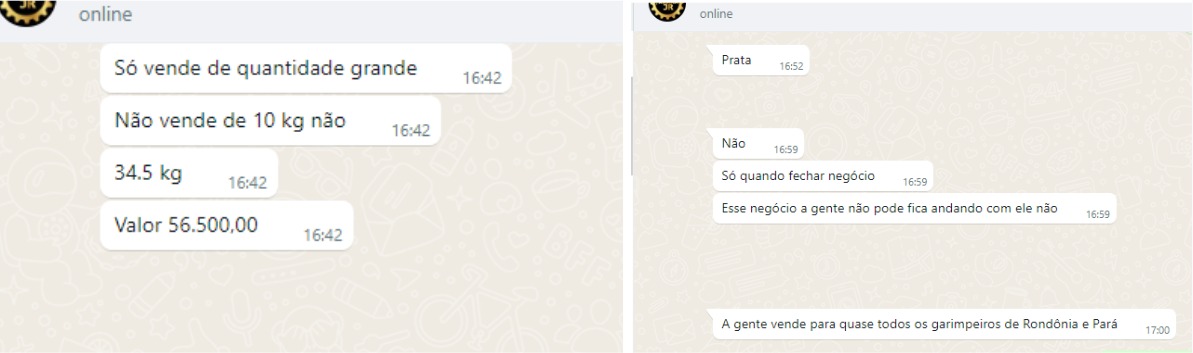

Bootlegging the Bolivian metal in Brazil isn’t hard. The seller told us that he could deliver the mercury in Porto Velho, the capital of the state of Rondônia, 329 km from the Bolivian border. He asked, however, that the deal be done in person in Guayaramerín and paid for in cash (either in Brazilian reais or bolivianos, the Bolivian currency). The price: R$ 50,000 for a cylinder with 34.5 kilos of mercury. When we later sought him out for this article, he declined to be interviewed.

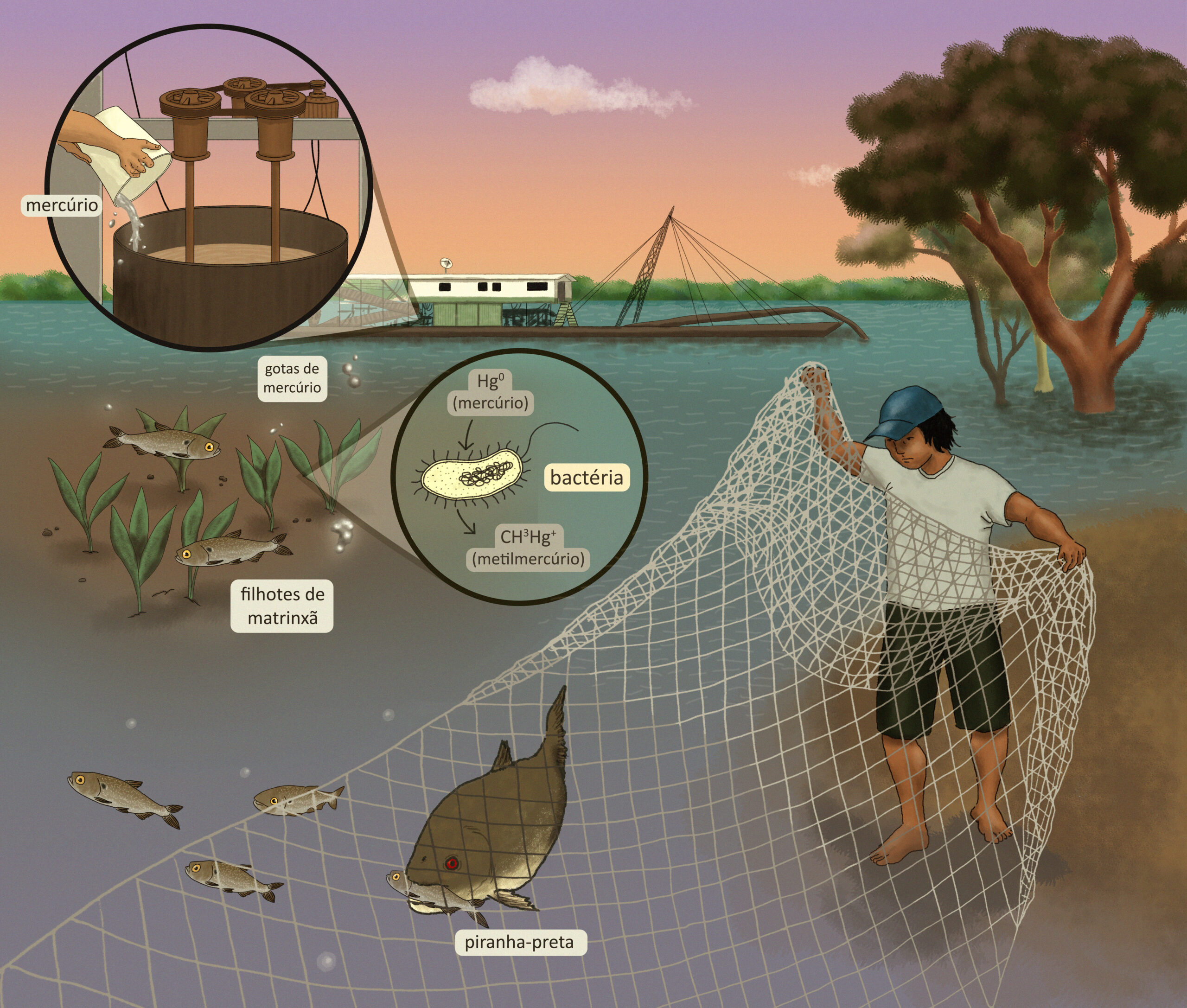

The highly toxic metal is used in its liquid form to extract gold at illegal mining operations. The mercury residue then contaminates the environment, affecting the people who live in mining regions or eat the fish that grow there. Mercury poisoning can cause Minamata disease, a neurological syndrome.

Minamata disease was identified in Japan during the 1950s in the city of Minamata, Kumamoto province, where some 5,000 people were poisoned. Many had severe symptoms and over 900 people died.

Since the Minamata Convention on Mercury was signed in October, 2013 when over 140 nations—including Bolivia—committed to reducing the use of the metal, it became almost impossible to purchase mercury legally in Brazil, which does not produce the liquid metal.

The United States and European nations also suspended exports after the treaty, while Brazil, Peru and Colombia reported a sharp drop in imports.

It was in this scenario that Bolivia emerged as the world’s largest mercury importer, ignoring the treaty’s targets for reducing its use and taking advantage of loopholes in the treaty allowing for continued imports, and for the use of mercury in small mining operations. In 2020, Bolivia was the destination of 75% of all mercury imported to South America.

IBAMA data obtained via the Information Access Law show that there has been no record of mercury imports for use in mining in Brazil since 2020. The country reduced legal imports at an average rate around 50% per year beginning in 2014 until, in 2021, Brazil had completely eliminated mercury imports. In turn, Bolivia—one of the few nations that did not restrict international mercury transactions—has increased its import volume of the metal by over 2,000% since 2013 according to data compiled by Chatham House on the Resource Trade Earth platform. It is estimated that up to half of this mercury has already been sent to illegal mining operations in Peru and Brazil.

The massive spread of new mining operations in the Brazilian Amazon since 2013 shows that, even with the elimination of legal imports, demand for mercury to be used in gold extraction has been met.

According to data from the MapBiomas network, the land area occupied by gold mining in Brazilian Amazonia has grown over 90%, from 79,000 hectares to 151,000 hectares since the Minamata Convention was signed in 2013. The area occupied by industrial gold mining grew by around 20% inside the biome over the same period.

The state of Pará, where the Indigenous Territories (ITs) of the Kayapó and Munduruku people are located, is one of the states most heavily hit by predatory mercury-based mining. There, ore extraction causes environmental devastation and invasion of Indigenous Territories and protected parts of the rainforest. Wildcat mining has multiplied by over 700% in the Munduruku IT since 2013, from 263 hectares of occupied land to 2,430 hectares.

Em terras indígenas, onde o garimpo é proibido, nota-se o crescimento exponencial da área ocupada nos últimos anos

The documentary film “Amazonia—the New Minamata?” by director Jorge Bodanzky explores the mercury contamination effecting Indigenous peoples in the rainforest today. The film shows the lives of the Munduruku living with mercury contamination in the mid and upper Tapajós regions, comparing the situation with what happened in Minamata, Japan.

Controls over the import, use and sale of mercury in Brazil are attributed to federal environmental watchdog IBAMA. Despite tight controls from the agency, one miner in the state of Pará, Marcos Flexa Saita, advertises mercury for sale online at the price of R$ 32,000 for a 34.5 kg bottle. “I can get you as much as you want,” we were told in a chat over WhatsApp. Unaware that he was talking with a team of reporters, Saita stressed that he delivers the mercury personally.

This salesperson is the brother of Wagner Flexa Saita, one of the owners of Midas Metais, accused in 2021 of involvement with the shipment of illegal gold. Midas Metais is also mentioned in a lawsuit by the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), in which it is accused of selling illegal gold in Itaituba, Pará, within the region where the largest areas of wildcat mining are located in Brazil.

On his Facebook profile, Marcos Saita also deals in land for prospecting, offers geological projection services and projects for the installation of prospecting and small mining operations—all of which are illegal activities.

When our reporters identified themselves as InfoAmazonia, Marcos Flexa denied selling mercury online and at illegal mining operations in Pará. After our conversation, he removed the ad from the internet. Wagner Flexa did not answer the questions asked by our reporters.

Our reporters also tried to contact the owner of Comercial Bryan, who had initially told us that she sold mercury inside her store. She did not, however, respond to requests for an interview.

Prospector cooperative sells mercury in Rondônia

The Mercury that crosses the Brazil-Bolivia border is camouflaged inside PET bottles, deodorant tubes and other small flasks that are transported in hidden compartments of car trunks or mixed in with other merchandise. First, the metal is taken to Porto Velho, state capital of Rondônia. The city is surrounded by prospecting operations and relies on shipping via the already-contaminated Madeira River and federal highways BRs 319 and BR-230, which facilitate transport of the mercury to Pará and southern Amazonas State.

Any importation, storage, transport and use of mercury in Brazil depends on authorization from IBAMA. However, authorities feel the penalties for crossing the border with the metal are mild.

“This monitoring isn’t easy to carry out and the smugglers are very quick and they know that Brazilian law for this type of crime is weak, because it classifies mercury trafficking as contraband,” we were told by Jairo Alves Carneiro, commander of the Rondônia Military Police’s Border Battalion. When caught at the border, criminals are tried for contraband and violation of environmental toxic substance control regulations.

This monitoring isn’t easy to carry out and the smugglers are very quick and they know that Brazilian law for this type of crime is weak, because it classifies mercury trafficking as contraband.

Jairo Alves, commander of the Rondônia Military Police’s Border Battalion

“When the mercury is used in mining, it falls under ‘environmental crime’, for example, and the penalties are heavier,” explains Carneiro, who has taken part in operations to combat mercury sales at the border.

Rondônia is the Brazilian state with the most reported cases of mercury seizures. Federal Police data show that there have been 79 cases of apprehended mercury since 2016. At least 62 cases (78%) happened in Porto Velho.

The Madeira River Prospectors Cooperative (COOGARIMA) sells mercury freely in Porto Velho. We easily confirmed availability over the phone but once we informed them that the motive for our call was for journalistic purposes, the organization’s directors didn’t want to give us an interview or give us any details about the origins of the mercury. COOGARIMA owns 98 mining areas on the Madeira River which are registered with the ANM (National Mining Agency). Thirty of these operations have authorization to used mercury—most renewed their mining rights in 2020 and 2021.

Gold prospecting in the Madeira River in Rondônia has been prohibited since 1991. Still, the mining continues illegally with the use of mercury, and has been increasing in recent years.

In January, 2021, Rondônia State Governor Marco Rocha (Liberal Party) issued a decree legalizing gold mining barges on the Madeira River. By July this year the Rondônia State Court declared the decree unconstitutional, shutting it down. In the tried request, the Public Prosecutor’s Office pointed out that the use of mercury in mining “diverges from the Brazilian Government’s international commitment in the Minamata Convention and legal provisions that regulate the use of mercury and cyanide for mineral extraction.”

A report from the Navy also identified the use of mercury in Brazilian gold mining operations brought from Bolivia.

We also exchanged messages with another supplier in Porto Velho who affirmed selling to “nearly all the prospectors in Rondônia and Pará” and that the minimum for purchase is 34.5 kilos, which fills a two-liter PET bottle, at the price of R$ 56,500. The value can vary according to the exchange rate. The man is a machinist that makes parts for mining machinery, but wouldn’t give us an interview to talk about the mercury business.

The long and winding road to the Brazilian border

Russia ranked first among Bolivia’s mercury suppliers in 2020, with 48 tons of the metal (35% of all imports), unseating Mexico, which exported 41 tons (30%) but continues as an important supplier because it also produces the metal. The rest of the mercury came from Tajikistan (14%), Vietnam (9.5%) and Turkey (6.3%).

Russia did not appear on the list of mercury exporters to Bolivia before 2019. Specialists say there is a triangular relationship between mercury producing nations and gold buyers on the global mercury market. Russia, for example, began importing mercury from the United Arab Emirates, which has a great interest in refined gold, and exports to Bolivia and India. But the Arab Emirates does not produce mercury. Rather, they buy it from Tajikistan, the planet’s largest producer of the metal.

The Bolivian government has refused to supply any information on mercury imports. According to independent organizations, once on Bolivian soil, the metal circulates freely in gold-producing towns, where parallel trade also takes place.

The Bolivian Public Defender’s Office says that “third parties who acquire mercury direct from importers may be those who sell this input in other parts of Bolivia such as Guayaramerín, on the Brazilian border.”

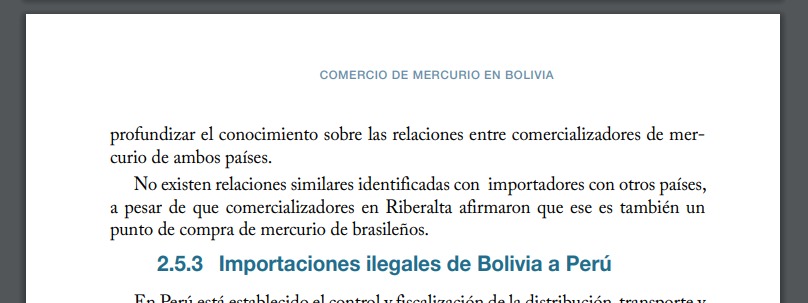

One hundred kilometers from the Brazilian border in the Bolivian mining region of Riberalta, mercury traders told CEDIB researchers that it was also a point of purchase for Brazilians. This would be the main route for mercury into Brazil.

One of the largest Mercury buyers in Riberalta is ASOBAL (the Madre de Dois River Barge Operators Association), and organization composed of 300 businesspeople who own 400 barges for use in gold prospecting. Our reporters spoke with the miners who work on these craft and they affirm that anyone can buy mercury from the Cooperative.

We scheduled an interview with the directors of ASOBAL at the co-op’s building in Riberalta, but when we arrived, they looked at our journalist credentials and the meeting was cancelled.

“We have known about gold, mercury and diesel sales on the Guayaramerín border since at least 2015,” said sociologist Oscar Campanini Gonzalez, director of CEDIB, the Center for Documentation and Information on Bolivia, and author of studies on the use of mercury in Bolivian mining.

Despite being a signatory to the Minamata Convention, the Bolivian government has not yet presented a national plan of action to mitigate the use of mercury in small-scale mining as provided for in the treaty. The document should have been presented in May of this year to the Executive Secretariat of the Minamata Convention.

Coordinator of IPEN (the International Network for the Elimination of Pollutants) Björn Beeler has been following compliance to the Minamata Convention in over 100 countries. He believes that the group most benefitting from the lack of monitoring on mercury sales is the global gold market that was “able to hide behind and obtain exactly what it wanted from the treaty—free-flowing mercury for gold mining.”

IPEN has supported the scientific identification of mercury contamination cases in nearby communities or with people directly associated with mining, including Indigenous peoples or riparian communities in the Brazilian and Bolivian Amazon. About the argument that defends the subsistence of small mining operations, Beeler says there are interests at play that are harmful to traditional communities. “If mercury is traded freely, there are no controls to contain mercury contamination and the violation of human rights,” he adds.

In Bolivia, where mining generates 6% of the GDP, the State has proven to have little power to enforce the terms of the Minamata Convention. Data compiled by CEDIB show that 84% of the mercury imported to Bolivia is used in mining. A spall parcel goes to the chemical industry (1.4%) and laboratories (0.7%).

And the number of companies without any connection to the use of mercury like hardware, clothing and appliance shops that end up with nearly 10% of the imported mercury is noteworthy.

Bolivian environmental law from 1995 regulates the manipulation of dangerous substances including mercury, and requires special authorization for the use, transport, storage or sale of them. In practice, this law is completely ignored.

Unfortunately, there are no effective actions on the part of the Bolivian government. There is no desire to create specific control and import regulations. There are no mandatory and operational monitoring mechanisms (for tracking).

Björn Beeler, Coordinator of IPEN

“Unfortunately, there are no effective actions on the part of the Bolivian government. There is no desire to create specific control and import regulations. There are no mandatory and operational monitoring mechanisms (for tracking). Regional and bilateral actions haven’t moved forward significantly in controlling this illegal trade,” explained Gonzalez.

In March of this year, the Brazilian embassy in La Paz advised the federal government in Brasilia about illegal entry of contraband mercury to Brazil and the political difficulties that the neighboring nation had in controlling imports and domestic trade.

Yet no specific measures were taken by the Brazilian government to contain contraband Bolivian mercury. We sent queries to the Ministry of Justice to find out which measures had been taken after the communication, but we received no response.

UN Rapporteur wants to get mercury out of wildcat mining operations

Marcos Orellana, special rapporteur to the United Nations on Toxins and Human Rights, has already classified the Bolivia question as a “regional problem” and in July this year proposed changes to the text of the Minamata Convention to prohibit international mercury trade and banish its use in small-scale gold mining within five years.

“Bolivia affirmed that it is preparing a national plan of action to eliminate the use of mercury. However, at the moment I am concerned with the lack of tangible progress in this direction on Bolivia’s part,” affirmed Orellana.

I have hopes that nations like Brazil, which deal with the problem of artisan miners using mercury inside its territory, will take the necessary lead to promote a reform of the Minamata Convention and begin to eliminate the human rights violations.

Marcos Orellana, special rapporteur to the United Nations on Toxins and Human Rights

“I have hopes that nations like Brazil, which deal with the problem of artisan miners using mercury inside its territory, will take the necessary lead to promote a reform of the Minamata Convention and begin to eliminate the human rights violations that people are suffering because they are exposed to contamination by this dangerous metal.”

The gold prospecting that happens in Brazilian Amazonia today is no longer what falls under the description “artisan”—using rudimentary materials and on a small scale. Funded by businesses from the gold supply chain and a strong lobby that has established itself in Brasilia, gold mining has become a giant industry using heavy machinery in the most remote regions of the rainforest.

Old time prospectors that actually panned for gold to earn their living today work for these mining operations. Work conditions are oftentimes the worst imaginable, and there are reports of conditions equal to slavery and child labor.

In the study-report “Gold siege—Illegal mining, destruction and struggle on Munduruku Territory” produced by the National Committee for the Defense of Territories Against Mining, researchers Luísa Molina and Luiz Jardim Wanderley narrate the changes Brazilian prospecting has undergone in recent years and how this structure has aligned itself with political lobbies and organized crime.

“What we have is highly mechanized prospecting under the wing of a network of people who finance extremely expensive machinery and an entire complex system of infrastructure and logistics,” states the document, which was delivered to the Brazilian authorities.

Brazil’s current president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was not reelected and will leave his job in 2023, was a strong supporter of wildcat mining in Amazonia and is currently trying to fast-track a bill through Congress (PL-191/2020) that would allow mining in Indigenous Territories.

Indigenous people and riparian communities in Amazônia have been contaminated

In July of this year, InfoAmazonia showed how Mercury poisoning is already affecting the Munduruku people. These people are experiencing neurological symptoms of Minamata disease including alterations of attention, reduced concentration and loss of sensation in the hands and the feet.

Mercury contamination is spread through the aquatic food chain, causing many predatory fish to accumulate dangerous levels of mercury which are then passed to the people who eat them.

This affects the kidneys and heart and causes permanent brain damage. Women of childbearing age are especially at risk due to the fact that exposure to mercury can cause congenital defects and harm to the developing fetus.

According to the United Nations, small-scale gold mining is the biggest cause of mercury poisoning on the planet today.

Studies published in 2021 by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) identified that all the Munduruku people living in three villages inside the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Territory had mercury in their bodies. Toxic levels exceeding the limit allowed by the World Health Organization were identified in 60% of these people.

Brazil signed the Minamata Convention in 2013, but the federal government only ratified it in 2018. Congress has been debating bill (PL 5490/2020) to create the National Mercury Contamination Eradication Plan since 2020.

Translated by Maya Johnson

This story was produced in partnership with the documentary “Amazônia, a Nova Minamata?” (The Amazon, A New Minamata?), by Jorge Bodanzky, with support from Ocean Films, Films4Transparency (F4T) and Journalists 4 Transparency (J4T). It also has the support of Report for the World, a The GroundTruth Project initiative.