Indigenous Chief Cu’tetet Krenjê walks briskly among buriti, babassu, and courbaril trees. His firm pace carries the urgency of someone who recognizes an approaching threat. The previous night, his expression hardened when he found out from InfoAmazonia reporters that more than half of the Krenyê Indigenous Land, won after decades of resistance in Brazil’s Maranhão state, is designated for natural gas exploration by Eneva, one of the country’s largest private energy producers.

Brazil’s Federal Constitution prohibits exploration of fossil fuels: Water resources, including energetic potentials, may only be exploited, and mineral riches in indigenous land may only be prospected and mined with the authorization of the National Congress, after hearing the communities involved, and the participation in the results of such mining shall be ensured to them, as set forth by law. on Indigenous lands without congressional authorization and without properly consulting these populations. Even so, a block called PN-T-117 overlaps approximately 75% of the Krenyê Indigenous Land. It was granted in 2017 by the National Agency for Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP). Eneva received a license from the Maranhão State Environmental Department (SEMA) to drill at least two wells within the territory, one of which is located 20 kilometers from the territory. This is the only active oil and gas block – in this case, in its exploration stage – overlapping an indigenous territory in the Legal Amazon: The Legal Amazon is a geographical area established by the Brazilian government in 1953 for economic planning and regional development purposes. It encompasses nine states: Pará, Amapá, Tocantins, Rondônia, Roraima, Amazonas, Acre, Mato Grosso, and part of Maranhão..

This is exposed by Fueling Ecocide, a special series on oil exploration in protected areas all over the world, produced by InfoAmazonia and 12 international media outlets. Coordinated by the journalist collective Environmental Investigative Forum (EIF) and media network European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), the investigation shows that licenses to explore and produce oil and gas obtained by companies in the sector encroach on more than 7,000 protected areas worldwide, despite existing legislation and efforts to preserve key biodiversity zones. In total, the overlapping area covers 690,000 km² – larger than France.

In Maranhão, in addition to the Krenyê Indigenous Land, Eneva’s blocks in the region also overlap at least five quilombola territories – Matões Moreira, Pitoró dos Pretos, Mocorongo, Santo Antônio dos Pretos, and Peixes – as well as environmentally sensitive areas such as river springs and priority zones for biodiversity conservation.

Block 117 is part of Eneva’s assets and serves as collateral for debt securities issued by the company and used to finance exploration in the area. Oil drilling and exploration activities are expected to begin “by 2026,” according to information released by the company itself.

The operation aims to supply the Parnaíba Thermoelectric Complex, located in Santo Antônio dos Lopes, a municipality in the south-central region of Maranhão. The complex includes six power plants, which are supplied with gas extracted from the blocks granted to Eneva. The company holds 15 blocks, totaling more than 3 million hectares – an area the size of Switzerland.

In recent years, the complex has been expanding its production of liquefied natural gas (LNG: Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) is natural gas that has been cooled to approximately -160 °C to be turned into its liquid state.), targeting the agribusiness route in MATOPIBA (an acronym for the area covering the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, and Bahia), where the axis of the fastest-growing agricultural frontier in the country is located (see more in Gas and agriculture: an alliance under a ‘green transition’ label). The two sectors – agriculture and energy – have joined efforts to occupy the region and turn it into a gas and grains transportation corridor.

InfoAmazonia asked Eneva about the licensing procedure for drilling in block 117 and about any overlaps with Indigenous territories, but the company did not respond. In a note, it only stated that “all Eneva projects are conducted with technical rigor and absolute compliance with environmental legislation, the rights of local communities, and the legal procedures established by relevant authorities.”

The reporting once again asked whether the company had informed the Krenyê Indigenous people about gas exploration in their territory, but Eneva again did not directly address the questions. Instead, the company stated that it “reaffirms that it fully complies with all procedures required by the relevant authorities to obtain licenses and authorizations, acting with transparency and responsibility at every stage of its projects”.

Indigenous land and gas exploration block were created almost simultaneously

Chief Cu’tetet takes us to the top of a plateau, where the forest spreads like a green blanket across the Maranhão Cerrado as far as the eye can see. The entire area overlaps block 117, in the transition region between the Cerrado and Amazon biomes.

The chief complains that the Indigenous people were never informed that part of the territory has been designated for gas exploration: “Here, in this place, we perform our rituals. We won this land with hard struggle, and it’s now sacred to us. The Krenyê suffered to get here. Since 1946, nobody would take responsibility, we were living on crumbs, so now we’ll fight for this land, as we have always done in our history.”

Here, in this place, we perform our rituals. We won this land with hard struggle, and it’s now sacred to us. The Krenyê suffered to get here. Since 1946, nobody would take responsibility, we were living on crumbs, so now we’ll fight for this land, as we have always done in our history.

Chief Cu’tetet

The procedure for creating the Indigenous Land began in 2013, after a court decision that ordered the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) to demarcate and designate a new area to guarantee the territorial rights of the Krenyê.

Returning to Pedra do Salgado – the Krenyê ancestral territory in Vitorino Freire, MA, from where they were expelled in the first half of the 20th century – was no longer an option since the area has been considered unable to provide for their physical and cultural reproduction because it was covered by pastures and scrubland, and its water sources are silted.

In extraordinary cases such as that of the Krenyê, Indigenous communities’ territorial rights can be recognized as Indigenous Reserves in partnership with state and federal land agencies. The Federal Government can buy, expropriate, or receive donations of land that will be used to establish the territory.

With some pride, Cu’tetet keeps the minutes of one of the final meetings that selected the land. After visiting several areas, on July 28, 2016, a commission agreed to purchase the property of just over 8,000 hectares in the municipality of Tuntum, also in Maranhão.

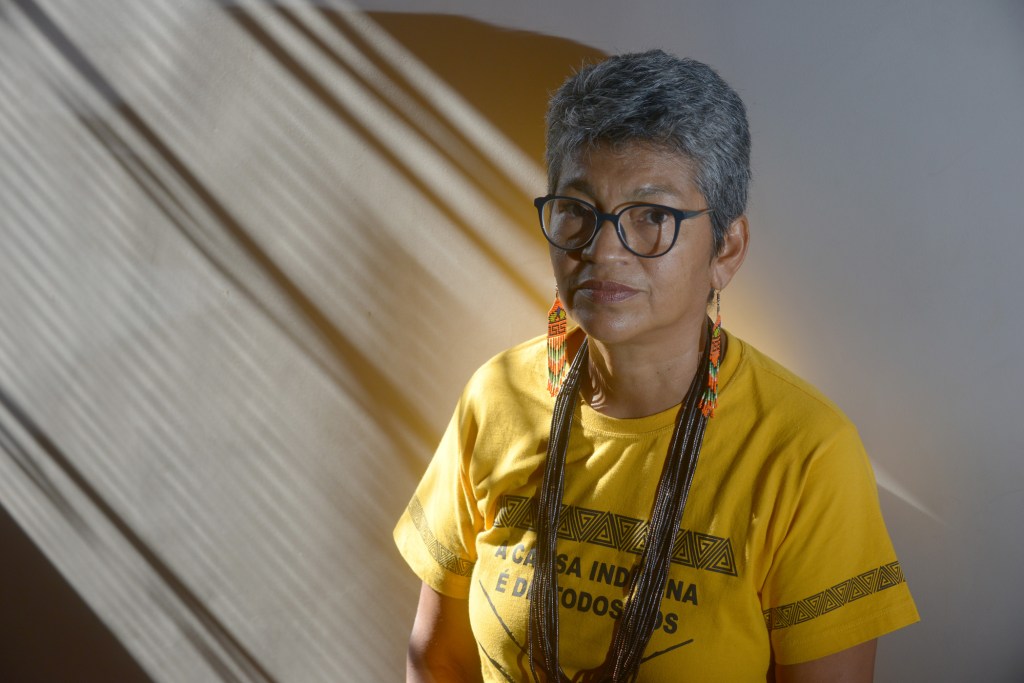

The meeting was held at FUNAI’s headquarters in Imperatriz, Maranhão. In addition to the agency’s officials, it gathered representatives of the Indigenous people, the property’s owners, and the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI). Rosimeire Diniz, a CIMI missionary who followed the procedures, confirms that “oil blocks were never mentioned” during the occupation of the current territory.

“They managed to secure this territory, which was won through lots of hard struggle and bloodshed, but also lots of joy, drums, maracas, and singing. Now, they are once again facing threats to their well-being. Such an overlap is like strangling all their hope, their freedom, their life there as a community after a history of suffering,” says Diniz.

Such an overlap is like strangling all their hope, their freedom, their life there as a community after a history of suffering.

Rosimeire Diniz, a CIMI missionary

Less than a year later, in 2017, the ANP announced an auction that included block 117. The demarcation procedure had already begun and the location for the Indigenous reserve had been selected, as shown in minutes of meetings, official letters, and resolutions led by FUNAI with assistance from the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA).

In the midst of the procedure to demarcate the Indigenous land, the ANP held the 14th Bidding Round for Exploration Blocks, which granted block 117 to Parnaíba Gás Natural, a company purchased the following year by Eneva. The resolution of Brazil’s National Council for Energy Policy, which authorized the auction, was published on April 11, 2017. The concession contract was signed in January 2018.

Also in early 2018, after the auction was authorized and given the delay in confirming the negotiation, the Krenyê decided to occupy the land. “The deal was already settled, FUNAI said they only needed the money to make the purchase. So we decided to occupy it,” recalls the chief.

In December of that year, FUNAI announced the purchase of the Vão do Chapéu e Outras Farm, which belonged to agribusiness company SC Agro Florestal LTDA, for R$ 14.1 million. While the negotiation with the company was concluded in 2018, the Krenyê were only informed in February 2019, after the payment to SC Agro Florestal was confirmed. On that occasion, then FUNAI president Franklimberg de Freitas was in the territory and delivered the deed to the Indigenous reserve to the Krenyê. The area was finally registered as property of the Union with the Indigenous people as usufructuaries.

Therefore, Eneva signed a concession contract in the midst of the procedure to demarcate the Indigenous territory, which was officially recognized in the same year. The two decisions – to exploit and to protect – have created a conflict that has been silent until now.

In a note to InfoAmazonia, the ANP denied any irregularity in the auction procedure for block 117. The agency sustained that “the homologation of the Krenyê Indigenous Land only occurred in 2018, after the 14th Round held by the ANP, which took place in 2017.” According to the agency, the auction procedure followed the regulations in force at the time, including a joint statement from the ANP, IBAMA, and state environmental agencies.

In June 2017, the ANP sent an official letter to FUNAI requesting a “brief analysis of the areas under study for the 14th Round” in order to “prevent any overlaps between the areas to be actioned and Indigenous Lands.” However, according to the ANP, FUNAI did not respond.

“Thus, the block offer followed all the procedural steps in force at the time, and therefore, there was no error in the inclusion of block PN-T-117 in the 14th Round’s auction,” ANP stated in a note.

When questioned by InfoAmazonia, FUNAI did not explain how communication with other agencies regarding the demarcation procedures for the Krenyê territory took place or which measures will be adopted to guarantee the rights of the Indigenous community.

License to drill

In 2025, the Maranhão State Environmental Department (SEMA) authorized at least two wells within Block 117. InfoAmazonia sought information from the state agency through various channels: we went to their headquarters in the state capital São Luís, contacted their press office, requested information about the licensing procedure under the Access to Information Act, and demanded action from their ombudsman’ office.

The aim was to obtain a public document describing the licensing procedure for Block 117, with the respective wells already authorized for drilling. By email, the state environmental department denied the existence of any territorial conflict with the Krenyê Indigenous Land: “Preliminarily, SEMA emphasizes that the license given to Eneva’s activities in Maranhão does not interfere with Indigenous lands located in the state.” However, the agency did not explain the existence of licensed wells in block 117. InfoAmazonia only obtained information about the authorization for the two exploration wells by researching on the State Official Gazette.

After being informed by InfoAmazonia about the overlap of the block with the Krenyê Indigenous Land, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) said that the area “cannot be explored and will have to be excluded [from the exploration block]”.

“Oil exploration on Indigenous lands is not regulated in Brazil and is currently prohibited. Therefore, if any new Indigenous Land is established after the acquisition [of the block], this overlapping area must be removed from the scope of the licensing,” IBAMA clarified.

Oil exploration on Indigenous lands is not regulated in Brazil and is currently prohibited. Therefore, if any new Indigenous Land is established after the acquisition [of the block], this overlapping area must be removed from the scope of the licensing.

IBAMA

In 2021, the Krenyê Indigenous Land had been definitively demarcated. Nevertheless, the following year (2022), the ANP renewed Eneva’s contractual deadline for the completion of the exploration stage, keeping the same limits of the area licensed in 2017. Exploration must begin by May 2026, which is the deadline for the start of the drilling stage in the block’s area. Juliana de Paula Batista, a lawyer who specializes in Indigenous rights, believes that there may have been miscommunication between federal agencies, but she stresses that, with the territory demarcated, the rights of Indigenous peoples must prevail.

“The Indigenous land has been purchased. Now it must be removed from the ANP’s database. But if the purchasing procedure had begun, the ANP could not simply put it up for auction.” According to her, the other option to avoid conflict “would have been for FUNAI not to have purchased this area and to have sought another one.”

In response to InfoAmazonia, FUNAI reaffirmed that exploration of fossil fuels on Indigenous lands is not regulated, which constitutes “an impediment to the exploration of blocks overlapping Indigenous lands.” It also stated that it is up to the operators to comply with the environmental requirements for licensing the activity, “which is essential for impact assessment.” When questioned, FUNAI did not clarify whether it was informed and consulted about the licenses granted last year for drilling in block 117.

Old impacts

Gas exploration in the Parnaíba River Basin gained momentum in 2008, when MPX Energia, a company created by businessman Eike Batista, acquired the first block in the region – the company would later become Eneva. The project adopted the “reservoir-to-wire” model, which integrates gas extraction and production by building thermoelectric plants close to gas deposits. In 2013, German company E.ON injected capital precisely when the construction of the Parnaíba Thermoelectric Complex took place in Santo Antônio dos Lopes, MA.

The arrival of the project was marked by land conflicts and forced removals. The old Demanda community, formed almost a century ago, was prevented from accessing a 900-hectare area purchased by Eneva. Deprived of babassu palm groves and streams, the families lost their main livelihoods. According to the Federal Prosecution Service (MPF) and the State Prosecution Service (MP/MA), about 6,000 babassu palm trees were felled to make way for the power plants.

In 2015, the agencies filed lawsuits against Eneva and the state government, pointing to the State Environmental Department’s omission in monitoring and adopting measures to protect the affected populations. In addition to resettling families, the requests included compensation for collective moral damages and implementation of compensatory and mitigating measures, which are still underway in the community.

An anthropological report commissioned by the Federal Prosecution Service revealed serious flaws in impact studies and non-compliance with environmental requirements. The document, signed by anthropologist Maristela de Paula Andrade from the Federal University of Maranhão (UFMA), warned about the risk of co-opting community organizations and creating economic dependence on the company – a prediction that, according to lawyer Diogo Cabral from the Maranhão Agroecology Network (RAMA), was eventually confirmed: “Given the circumstances, the communities’ dependence on the company would be inevitable.”

Resettlement was then included as a compensatory measure, according to the prosecutors. In 2016, families were relocated to the edge of the BR-135 highway, in two settlements named Nova Demanda. Today, some of the residents work on projects linked to Eneva – from supplying the city hall with food items to corporate coffee breaks, in addition to providing services in the power plant’s workshops.

Almost ten years later, the families have changed their lifestyle and way of life. Nildete Vieira de Melo Silva, 53, who used to live off breaking babassu coconuts in a mud house, now cultivates passion fruit and is part of the Nova Demanda Agroecological Family Producers Association (APRAND).

She acknowledges that the prosecutors’ actions improved the conditions for negotiation and consequently the compensations provided to the community.

“It did get better, the houses are all masonry, they were furnished, each with three hectares of land per family. We received courses and training,” she says. Today, she participates in the “Women Entrepreneurs” project, also promoted by Eneva.

Nonetheless, structural problems and economic dependence persist. Residents report constant power outages, and some houses had cracks that required reconstruction. In August last year, the local school had to be closed for the same reason. In addition, virtually all of the association’s services and deliveries depend on intermediation by Eneva or companies it designates.

In Capinzal do Norte, a municipality neighboring the Complex, where the company supports the Association of Babassu Coconut Breakers (AMQCB), women report scarcity of babassu trees and restricted access to the remaining groves, almost all of which are located on private farms.

“Today we have to go very far to get the babassu, and we depend on a car from the City to bring them home and break them,” says Maria Vilani Lopes, 32. The AMQCB pays R$ 6 per kilo of babassu, which is processed into products. “On a good day I can break 10 kilos,” she says.

Vulnerable area

Environmental reports presented in 2015 and 2017, during the bidding procedures for blocks in ANP auctions, indicate that the Parnaíba Basin area was classified as a highly ecologically sensitive area, mainly due to its biodiversity. The first report also recommended that conservation units as well as Indigenous and quilombola territories be considered in licensing procedures.

Blocks 117 and 133 overlap the buffer zone of the Mirador State Park, an area planned for the creation of the Mirador Mosaic – a special land management category that integrates different conservation units and other adjacent areas. The territory is aimed at protecting the headwaters of the Alpercatas and Itapecuru rivers, endangered species such as the puma, and the traditional communities that live in the area, including the Krenyê and Canela Indigenous Peoples, as well as residents of the park and surrounding areas.

The mosaic is intended to restore part of an area of approximately 100,000 hectares excluded from the Mirador Park in 2009 by the Maranhão State Parliament.

Farmer and community leader Joaquim Alves de Souza, president of the Agroecological Cooperative for Life of the Southern Maranhão Cerrado (COOPEVIDA) and a member of the board of the Mirador State Park, lives on the front line of this dispute.

“We are at the entrance to MATOPIBA, this monster that is advancing over family farming and traditional communities. The mosaic is a way to bring Indigenous lands, the park, and the communities together so that we can protect ourselves and continue living well in these territories,” said Souza, who is currently engaged in the implementation of agroforestry systems integrating the cultivation of orchards, grains, and vegetables with the environment.

We are at the entrance to MATOPIBA, this monster that is advancing over family farming and traditional communities. The mosaic is a way to bring Indigenous lands, the park, and the communities together so that we can protect ourselves and continue living well in these territories.

Joaquim Alves de Souza, president of the Agroecological Cooperative for Life of the Southern Maranhão Cerrado (COOPEVIDA)

Like most local residents, Souza does not know the details of gas exploration. “These large projects, whether gas or agribusiness, end up being harmful to everyone who still resists in rural areas. The land becomes more valuable, there is pressure to sell, and small farmers, without support or technical assistance, end up being pushed out.”

For Diogo Cabral, the lack of transparency and dialogue about gas exploration in this area violates the right to free, prior and informed consultation (FPIC) of the affected populations: “Convention 169 guarantees traditional populations’ right to be consulted on any project or administrative act that impacts their way of being and existing. And I can assure you that there was no consultation process. This involves Indigenous peoples, babassu coconut breakers, and quilombola communities.”

In some communities, such as the Matões Moreira quilombo – completely overlapped by a gas block of the complex, PN-T-68 – InfoAmazonia found gas production fields less than 5 kilometers from the territory’s boundaries.

“It’s a violent form of production that directly impacts the way of life of these communities. They had to be heard,” Cabral argues.

It’s a violent form of production that directly impacts the way of life of these communities. They had to be heard.

Diogo Cabral, lawyer

Exploration vs. development

Santo Antônio dos Lopes is one of Brazil’s municipalities that receive the most royalties from gas and oil exploration. According to the 2022 Census of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the local GDP per capita reaches R$ 210,000, the 48th highest in Brazil – almost four times that of Santos, the city with the country’s largest port. The average income of formal employees is 3.9 minimum wages, one of the highest mona Brazilian municipalities.

But these figures hide inequality. The Municipal Human Development Index (IDHM) is low, ranking 4,921st among the 5,570 Brazilian municipalities, and only 12% of households are connected to the sewage system. In the center of the city that supplies the country with energy, waste still runs along the sidewalks.

Residents living near the Complex report worsening water quality, power outages, and respiratory problems. There are Eneva’s gas extraction wells in the area, where it is possible to see the burning of surplus natural gas – a practice especially common in remote areas of the Amazon, where lack of infrastructure hinders its capture and processing.

“At first, my children complained of headaches, but then we got used to it. Sometimes the smell of gas is strong, it must be harmful, but nobody explains anything,” says Raimundo Nonato Sabino, who owns a cachaça (Brazilian sugarcane rum) distillery that has been operating in the same place for three generations. Since 2010, they have shared the land with four gas production wells. The flare tower burns the extracted surplus almost uninterruptedly.

At first, my children complained of headaches, but then we got used to it. Sometimes the smell of gas is strong, it must be harmful, but nobody explains anything.

Nonato Sabino, who owns a cachaça (Brazilian sugarcane rum) distillery

According to Sabino, Eneva pays R$ 6,000 per month to lease the plot and because part of the area is now useless for him to plant sugarcane to supply the distillery. One of his sons works at the company’s gas plant.

Gas and agribusiness: an alliance under a ‘green transition’ label

In recent years, in addition to expanding the exploration of fossil fuels for energy generation, Eneva has invested heavily in LNG production, presented as an alternative to “decarbonize” supply chains and as a “transition fuel.” The company expects to increase that production by up to 50% by 2027.

Since 2024, Eneva has been promoting what it calls the “largest road-based logistics corridor focused on reducing CO2 emissions.” The initiative focuses on transportation of products manufactured in the MATOPIBA area using LNG-powered trucks, which promise to be up to 20% less polluting than diesel engines.

The plan brings together the gas industry and agribusiness, based on the same “energy transition” rationale in the form of a joint venture between Eneva and Virtu, a Brazilian transportation logistics company, in partnership with the Swedish company Scania. Eneva supplies the fuel; Scania provides the LNG-powered trucks; and Virtu transports the cargo.

When questioned by InfoAmazonia, Scania said it “keeps a firm commitment to producing and marketing vehicles for its customers, offering solutions and technologies that contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, especially in the transportation and logistics sector.” When questioned, Scania did not respond as to whether it was aware of the overlaps between Eneva’s gas blocks and protected territories.

If you look closely, there is no energy transition in this model. All the movement points towards increasing production. We will still face a lot of this discourse about the return of thermal power plants.

Ricardo Baitelo, IEMA project manager

The Ten-Year Energy Expansion Plan 2032, prepared by federal government’s Energy Research Company, provides for the construction of a gas pipeline from the Maranhão complex to Barcarena, in Pará state, where LNG will be loaded directly onto tankers that will take the fuel to other parts of the world.

In the second quarter of 2025, production at the Parnaíba Complex increased by 381% over the same period last year.

According to data from the 5th Inventory of Atmospheric Emissions in Thermal Power Plants conducted by the Institute of Energy and Environment (IEMA), Eneva’s Parnaíba I and V power plants led CO2 emissions from electricity generation in 2024. At least three of the five Eneva plants operating in the Parnaíba basin were among the top CO2 emitters.

The attention given to thermal power plants as an energy alternative prevents the country from expanding the share of renewable energies in the energy model, according to IEMA project manager Ricardo Baitelo, who holds a PhD in Energy Planning from the University of São Paulo (USP): “If you look closely, there is no energy transition in this model. All the movement points towards increasing production. We will still face a lot of this discourse about the return of thermal power plants.”

According to the inventory, gas-fired thermal power plants emitted about 9.4 million tons of CO₂ in 2024 – virtually the same amount generated by deforestation recorded in Altamira, which was the second most deforested municipality in the same year (12.9 MtCO2) and more than half of the emissions from all thermal power plants, including those fueled by oil and coal.“A myth has been created that natural gas is the transition fuel. We are already experiencing the effects of climate change firsthand, and yet we continue to bet on fossil fuels,” explains Anton Altino Schwyter, project analyst at IEMA and a PhD candidate in energy at USP.

A myth has been created that natural gas is the transition fuel. We are already experiencing the effects of climate change firsthand, and yet we continue to bet on fossil fuels.

Anton Altino Schwyter, project analyst at IEMA and a PhD candidate in energy at USP

Whith deep regret, InfoAmazonia reports that Chief Cu’tetet Krenjê passed away on January 3, 2026, after this report was finalized. Cu’tetet, unfortunately, will never know the outcome of the story regarding his own territory. In a statement, CIMI Maranhão described him as a “great warrior, wise man, and a major leader, an organizer of the Web of Peoples and Traditional Communities.” In tributes posted on social media, relatives said that Cu’tetet “did not depart. He returned to the village of the ancestors. His strength lives on in the Krenyê people”.

Investigative reporter: Fábio Bispo

Data analysis: Renata Hirota

Data visualization: Carolina Passos

Editing: Carolina Dantas

Editorial direction: Juliana Mori

This story is part of the series “Fueling Ecocide”, developed by EIF, a global consortium of environmental investigative journalists, in partnership with the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network, and their partners Daraj, InfoAmazonia, InfoCongo, Der Standard e The Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

This investigation was supported by the Journalismfund Europe and by IJ4EU (Investigative Journalism for Europe).