Copper, lithium and nickel, among others, are raw materials used to produce electric vehicles, batteries, wind turbines, and solar panels. The Amazon holds part of these minerals, and large companies want to exploit it. Most mining applications are in Pará state, and some of them will have direct impact on areas located in Indigenous Lands and Conservation Units.

The plans of rich countries – especially China, the United States and the European Union – to curb global warming are based on some important keywords. One of them is the ‘energy transition,’ that is, replacing an energy model that uses fossil fuels such as oil and coal with a different one of fewer greenhouse gas emissions. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in order to produce electric vehicles, solar panels, batteries and wind farms – which are crucial to this energy shift – the demand for minerals such as copper, lithium and nickel will increase fourfold by 2040 over 2020.

The Amazon holds part of these several minerals and is one of the places where large mining companies concentrate their efforts. An exclusive survey by InfoAmazonia based on mining procedures open at Brazil’s National Mining Agency (ANM) until May 24, 2024 found 5,046 applications filed by 807 companies to exploit ores considered essential for the energy transition in the Brazilian Amazon. The applications for copper, aluminum, manganese, niobium, silver, nickel, cobalt, rare earths: The set of 15 chemical elements made up of the lanthanide family plus yttrium are called Rare Earths. The elements are as follows: Light ones: lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium and neodymium; Mediums: samarium, europium and gadolinium; Heavy: terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, lutetium and yttrium. They are used in neodymium magnets by the electric vehicle industry and in the construction of wind turbines and industrial automation. and lithium cover 64 million acres [26 million hectares] within the biome.

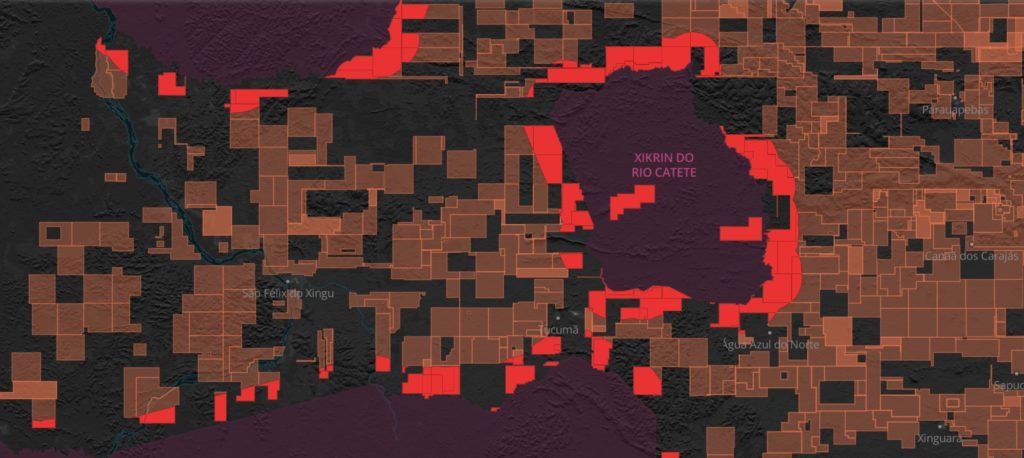

Strategic minerals for the energy transition in the Brazilian Amazon. On the map, hover your mouse cursor over the orange areas to see information about the applications, such as substances involved, companies, years of application, among others. Click on purple areas for information about indigenous lands and on green areas for details about conservation units.

This race for mineral raw materials reveals a contradiction in the international ‘clean’ energy project: while countries like China and the US boost their production of electric vehicles and batteries, electricity barely reaches some parts of the Amazon. Furthermore, experts interviewed by InfoAmazonia are concerned about how this exploitation will be carried out without putting pressure on traditional populations and impacting the biome’s ecosystem.

“There is a lot of talk about how we are going to do well in this low-carbon economy but no clear policy on how this will actually happen. What are the safeguards? The main concern has to be how we are going to exploit these resources,” says Marta Salmon, senior analyst at the Talanoa Institute, a non-profit organization focused on climate policy.

There is a lot of talk about how we are going to do well in this low-carbon economy but no clear policy on how this will actually happen. What are the safeguards? The main concern has to be how we are going to exploit these resources.

Marta Salmon, senior analyst at the Talanoa Institute

At least 1,205 of the projects mapped by InfoAmazonia are within the area with direct impact on 137 indigenous lands (ILs) located up to 6.2 miles [10 km] from their boundaries. In 390 cases, mining areas invade these territories, which is banned by Brazil’s Constitution. The survey also found 1,207 applications that overlap 107 conservation units (CUs) in the Amazon.

THE LEGISLATION ON BUSINESS ENTERPRISES IN INDIGENOUS LANDS

According to Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO-169), which is legally binding, traditional communities – including indigenous peoples, quilombola, and riverside dwellers – have the right to free, prior and informed consultation on any enterprise or administrative measure that interferes with the autonomy of their territories. They even have veto power.

The Convention does not set specific parameters to define impacts on indigenous or traditional use lands. These impacts are assessed by studies conducted specifically for each project.

In 2015, interministerial ordinance 60/2015 established a minimum radius of 6.2 miles [10 km] around indigenous lands to determine impacts on communities and require projects to apply for a federal license. In all these cases, the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) and the communities must be consulted in advance.

Mining in indigenous lands is banned and could only be authorized by an amendment to the Constitution passed in Congress.

The protected areas under the heaviest pressure are in Pará state. The indigenous lands include: the Xikrin Mebengôkre people’s Xikrin do Cateté IL, with 93 mining applications; the Kayapó, with 85; and the Munduruku people’s Sawré Muybu IL, with 77. As for conservation units, the National Forests (known as FLONAS) of Jamanxim, with 132 applications; Carajás, with 85; and Itaituba II, with 81 have the most applications for exploitation of energy transition ores. Pará concentrates more than half of all licensing procedures in the Amazon for these minerals, with 3,069 applications filed with the ANM to explore 36 million acres [14.6 million hectares] – an area larger than the entire territory of England.

Since the beginning of the Lula administration in 2023, the ANM has been reviewing mining applications that overlap indigenous territories. Last year, the agency denied more than 400 applications in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, but according to ANM’s own data, there are more than 2,000 licensing procedures overlapping indigenous lands.

In addition, recent pressure on large companies regarding mining in indigenous lands means that new projects in the Amazon will have to resort to areas outside the territories but close to their boundaries, which, according to experts, does not eliminate the impacts on these areas.

This is what happens in indigenous lands in southeastern Pará, virtually surrounded applications to mine copper and nickel. It also happens with applications for niobium in the surroundings of the Yanomami IL, where the Geological Survey of Brazil (SGB) indicates the existence of deposits near the boundary of the territory, where high-value minerals are concentrated.

Companies interested in exploiting minerals

Vale, Anglo American, Nexa, Codelco and Bemisa are among the 800-plus companies seeking energy transition minerals in the Amazon, including projects with potential impact on indigenous lands and located within conservation units.

ANM data shows that mining company Vale has filed 295 applications to exploit these metals in the Amazon biome. At least 139 of them overlap conservation units and 65 are in areas that potentially impact indigenous lands. At least 45 applications filed by Vale and its subsidiary Vale Metais Básicos are near the Xikrin do Cateté IL.

In April this year, the Onça Puma mine – one of Vale’s main nickel production projects, located around the Xikrin territory – had its Operating License suspended for not complying with environmental conditions imposed on the project. This is the fourth stoppage since 2011. The company appealed to Brazil’s Supreme Court (STF) and a new conciliation meeting is scheduled for June 20, 2024. The mine, along with acquisitions in Canada, consolidated Vale as the world’s largest producer of nickel, which is essential for electric cars, batteries, wind farms and green hydrogen.

“After they started mining, the river became polluted, and it is still polluted,” said Chief Bep Kroroti Xicrin from the Djudjekô indigenous village, which is located on the banks of the Cateté River, in the western part of the Xikrin do Cateté IL, near the Onça Puma mine. The indigenous leader states that the culture of the communities has changed, with reduction in fish affecting their diet and health. “Our culture no longer uses the traditional timbó vine fishing, we no longer fish, we avoid the river. Vale doesn’t respect indigenous people,” he said.

After they started mining, the river became polluted, and it is still polluted.

Chief Bep Kroroti Xicrin from the Djudjekô indigenous village

Questioned by InfoAmazonia, Vale stated, in a note, that “it complies with the socio-environmental conditions and controls imposed on its activities in Pará as determined by legislation and respecting neighboring communities.” The company says it continues to adopt the appropriate measures to seek to reverse the decisions.

In the case of the Anglo American mining company, of the 737 applications to explore copper and nickel in the Amazon, 353 overlap Conservation Units and 178 are in areas that impact Indigenous Lands. Together with Nexa Recursos Minerais and Bemisa, the company applied for exploiting copper in 2.048.000 acres [829,000 hectares] of the Jamanxim National Florest – 63.7% of all the 3.2 million acres [1.3 million hectares] of the protected area of. The applications started to be filed in 2017, when there was a boom in the search for these minerals in the Amazon.

In 2020, after being granted a license for copper exploration in the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Land, Anglo American faced indigenous protests that forced it to retreat. In the same year, a Federal Court in Pará suspended all applications for the Itaituba II National Forest, including Anglo’s. In 2021, the company formally requested ANM to withdraw applications in the Itaituba and Jamanxim National Forests and the Sawré Muybu IL, but some of them are still open and a license for exploration in the Jamanxim FLONA has been granted.

Some ANM decisions regarding Anglo’s withdrawal requests state that the applications will be shelved, and other companies may apply for the same areas in the future.

In the report, Anglo said that the ANM data “does not reflect the current situation” and that it is permanently working with the agency to have the database updated. The mining company states that “it does not have any license for exploitation on indigenous lands or primary forests in Brazil and that there are also no applications for nickel and copper within the Amazon biome.”

In 2023, Anglo transferred mining rights with a license for exploration in the Jamanxim National Forest and near the Apiaká do Pontal e Isolados IL to Bemisa Holding, controlled by banker Daniel Dantas. Bemisa has 90 mining projects in the Amazon for copper and nickel, with at least 10 applications overlapping the Jamanxim National Forest and five located within 6.2 miles [10 km] of the territory where the presence of isolated peoples has been recorded.

Nevertheless, Bemisa told InfoAmazonia in a note that “there is currently no prospect of a possible mineral asset operation in the Jamanxim National Forest or in the surrounding areas of the Apiaká do Pontal e Isolados IL.” The company says it adopts “environmental and social impact controls, with recognized operational excellence throughout Brazil.” However, in February this year, Bemisa announced it would resume exploration in one of the areas transferred by Anglo and which is entirely within the Jamanxim National Forest.

In 2017 and 2018, Nexa Resources filed 28 applications to mine copper in conservation units in the Amazon. Currently, the mining company has 33 open licensing procedures overlapping protected areas, some of which have had their applications withdrawn. Codelco do Brasil, a subsidiary of Chile-based Codelco, the world’s largest copper producer, has 135 applications to mine it in the Amazon. At least 22 of them are in areas that impact indigenous lands. The company has requested the withdrawal of some of them.

To InfoAmazonia, ANM informed that it carries out checks to find whether mining applications in certain areas will interfere with indigenous lands. “If the mining area completely overlaps an indigenous land, the application is denied,” the agency said. In the case of partial overlaps, “the part that interferes is excluded, and the company can choose to continue with the rest of the area where there is no interference.”

Regarding the alleged delays in analyzing withdrawal requests mentioned by mining companies, the ANM stated that “sometimes, it is due to the fact that the ANM effectively and necessary verifies the legitimacy of the requesting party in asking for the application to be withdrawn.” The agency reported that it is looking for ways to speed up the procedures.

Mineral potential in protected forest areas

The SGB points to the existence of large deposits of copper, aluminum, nickel and rare earths in the Amazon. Occurrences of lithium and graphite have also been recorded in the biome. Furthermore, in 2023, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) found potential in Brazil for mining lithium, nickel, manganese, neodymium and graphite to supply essential transition ores.

But, despite the attempt to present Brazil as an alternative supplier of these substances, lack of geological knowledge makes the estimated potential inaccurate. According to the SGB, only 37% of the Amazon territory has been mapped, and the potential for new mineral discoveries lies in preserved and protected areas of the forest.

“The lesser-known sectors represent the most remote areas, whether the biome is preserved, which generally include indigenous lands and border and/or environmental protection areas,” says an excerpt from a study prepared for the review of Brazil’s National Mining Plan 2050, which is not yet in force.

Researcher Marta Salmon worked on the report Strategic minerals and the energy transition released by Política por Inteiro, an initiative of the Talanoa Institute to monitor public policies focused on the climate. The document provides an analysis of Brazil’s Pro-Strategic Minerals (PME) policy created during the administration of former President Jair Bolsonaro to encourage strategic mineral production projects “for the development of the country.”

According to the report, the PME “does not address the challenges of safely exploiting critical minerals available in Brazilian territory.” Furthermore, an important point is that, despite including minerals essential for the energy transition, the federal government’s program neither mentions changes in energy models nor includes environmental advocates in the discussion and decision-making.

The definition of critical minerals varies globally, usually including those with lower occurrence or restricted geological location, in addition to related geopolitical and economic issues. The European Union has a list of critical raw materials, while the United States has a list of critical materials, which include specific minerals, both citing issues related to the energy transition.

Brazil’s Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy decided not to adopt the term ‘critical minerals,’ but rather ‘strategic minerals’ as a broader concept that included substances with are no related to the energy transition, such as gold and potassium, for example.

Even without a focus on climate adaptation, Brazil’s Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy has been the basis for investments aimed at climate issues in the mining industry. In May this year, the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) and mining company Vale announced the creation of an investment fund focused on energy transition projects, with contributions of up to R$ 250 million by the state-owned bank. The fund listed virtually the same substances as the Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy, with the exception of gold.

The new Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) launched in 2023 also provides for public investments of around R$ 281 million by 2026 in mineral research for the energy transition.

Questioned by InfoAmazonia, BNDES justified its dependence on fertilizer imports to keep substances such as potassium and phosphate among those supported by the new fund: “These are the main minerals used to make fertilizers, which are essential for reducing Brazil’s dependence on imports – now at 85%. The fund will support projects with minerals that are strategic for the energy transition, decarbonization and soil fertilization,” the bank stated.

The Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy has supported 19 projects so far, one of which is Belo Sun: Belo Sun was founded by Canadian bank Forbes & Manhattan, focusing on international mining projects., from the mining company with the same name founded by the Canadian bank Forbes & Manhattan to exploit gold in the Volta Grande do Xingu area. The project includes occupation of an area of 5,000 acres [2,000 hectares] of public land where around 800 families should be displaced. In 2022, a Pará state Court suspended the licensing procedure and required further socio-environmental studies and consultation with riverine and indigenous communities located “at least 6.2 miles [10 km] from the project, on both banks of the Xingu River.”

Belo Sun’s gold mining project in Xingu turned into a UN complaint against Brazil, Canada and the US. Another project of Canadian bank Forbes & Manhattan supported by the Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy is the Potássio Autazes project, which was granted licenses by the Amazonas state government to dig a mine on land claimed by the Mura indigenous people. The Public Prosecution Service filed a lawsuit against the project, pointing out violations of indigenous peoples’ rights and environmental risks posed by the project.

“It’s a Brazilian salad mixing mining and agribusiness interests,” pointed out Talanoa Institute’s report on minerals encouraged by the federal administration.

The Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME), which controls the Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy, did not respond to the InfoAmazonia’s questions.

Electric cars: ‘We must stop burning oil’, says scientist

The demand for clean energy – from wind turbines and solar panels to electric vehicles and battery storage – require a wide variety of metals. The type and volume will depend on the technology. While wind farm turbines require niobium and copper, electric cars need lithium and nickel, for example.

The IEA divided its projections about the demand for these materials considering two scenarios: sustainable development and declared policies, Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), and Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS).

The IEA’s sustainable development scenario considers the broad evolution of the energy sector to achieve the main energy-related goals of the UN, including those of the Paris Agreement (SDG 13), universal access to modern energy (SDG 7) and reducing energy-related air pollution and associated impacts on public health (SDG 3.9). The scenario of declared policies reflects the IEA’s view of the policies in force or announced by governments around the world.

In the sustainable development scenario, global utility-scale battery storage installation will see a 25-fold growth by 2040 compared to 2020. This demand will be primarily driven by electric cars.

The transition will also require more copper for electrical grids and for the construction of wind farms and electricity transmission; copper, silicon and silver will be crucial for photovoltaic energy generation; and a larger amount of rare earths will be essential to manufacture electric engines.

“This is important because we need to stop burning oil. Technically, it’s possible to do it right, complying with consultation to affected communities. What we need is for this to be politically possible as well,” said Instituto ClimaInfo researcher Shigueo Watanabe.

This is important because we need to stop burning oil. Technically, it’s possible to do it right, complying with consultation to affected communities. What we need is for this to be politically possible as well.

Shigueo Watanabe, Instituto ClimaInfo researcher

IEA projections indicate that the increase in demand for copper and rare earth elements for clean energy generation will exceed 40% by 2040 compared to 2020, while demand for nickel and cobalt is projected to grow between 60% and 70%. Lithium, in particular, will face an expected increase in demand of over 90%, making it the most widely used material in electric vehicles and battery storage.

The agency emphasizes that projections may change with technology development or replacement, especially for batteries, which seek new formulas and components for higher storage capacity and longer duration. Demand for cobalt and graphite may increase 6-30 times, depending on the direction of batteries’ chemical evolution.

In addition to critical minerals, metals such as aluminum and iron may see increased demand due to the process of replacing vehicles and equipment.

InfoAmazonia analyzed mining applications open at ANM on May 24, 2024, considering ores seen as essential for the energy transition according to the classification of international agencies and research centers.[See the survey methodology here].

This article was produced with support fromAmazon Watch.