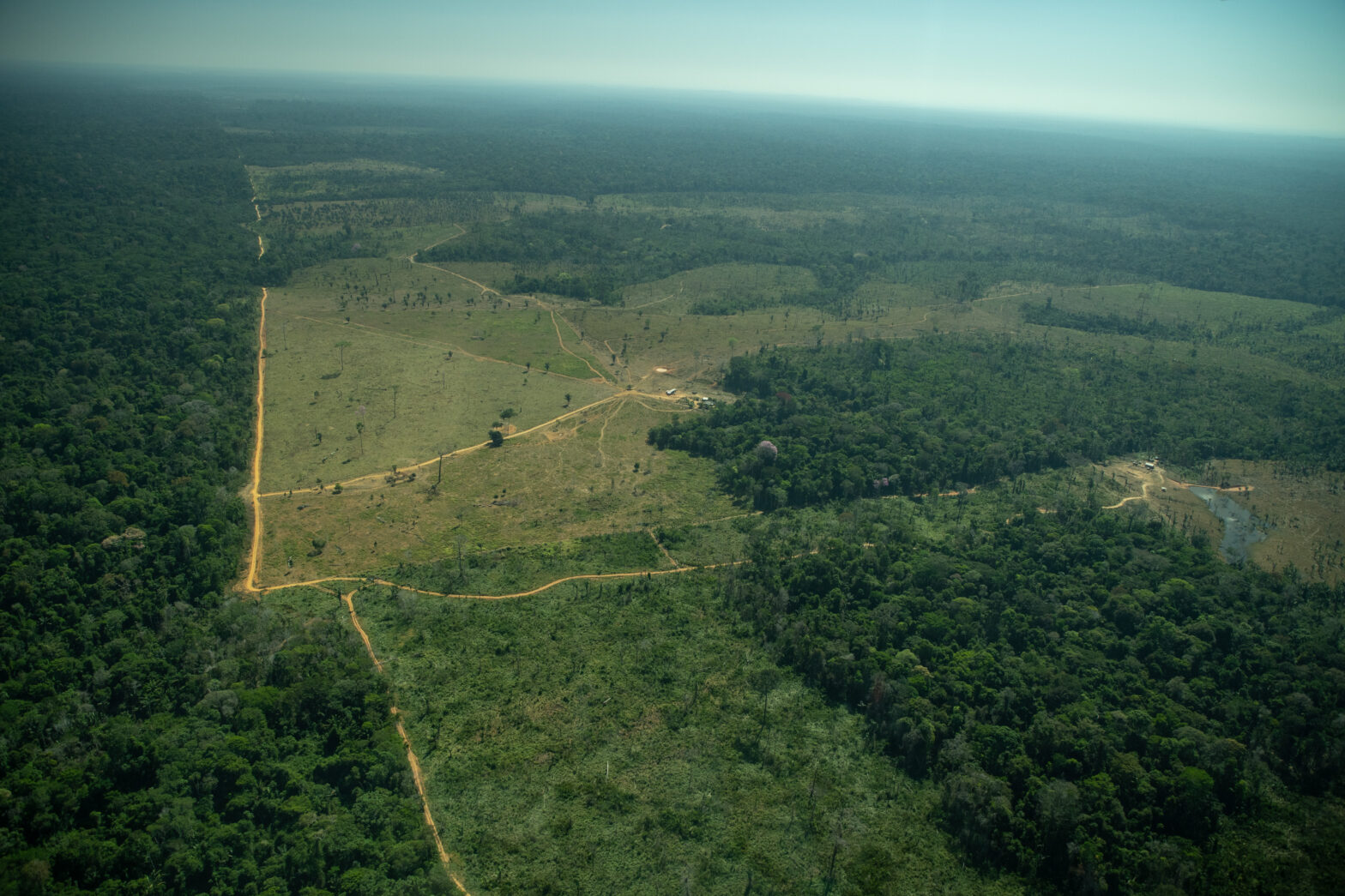

Lula promises to eliminate deforestation by 2030, but projections from the Ministry of Agriculture indicate a 17% increase in beef production in the next ten years, which could lead to the deforestation of one million hectares per year until 2030. Alternatives to further clearing of the forest are the restoration of the pastures and an increase in productivity, allied with oversight measures that put an end to illegal land grabs.

“A year ago, we made an investment to reform the pastures and we saw the result there. We were able to increase the number of heads, but without the need for new area,” says Fernando Lucas Luczinski of the 166 hectares where he raises beef cattle with his father in Alta Floresta, Mato Grosso. “The replenishment of 24 hectares of the property with fertilizer and lime has already resulted in an increase in pasture production.”

Among the improvements made with support from a consultant, Luczinski introduced rotational grazing on eight hectares of the farm. The technique consists in dividing the pasture into smaller areas, with the cattle moved according to a system of rotation in order to provide time for the area to regenerate.

In addition, running water represented a differential in production: Since the animals tend to graze close to water, distributing it better results in more efficient management of the pasture with productivity increasing as a consequence, as well as reduced spending on logistics and staff. However, the measure can be extended further: “We aren’t able to introduce it for the entire herd. There are small batches that make use of this benefit.”

With the Legal Reserve: a portion of native vegetation that must be maintained on rural properties and whose dimensions vary according to each biome. respected and the Areas of Permanent Preservation: zones, whether covered in native vegetation or not, geared toward the preservation of the water, the landscapes, the ecological balance, the soil and human well-being. fenced in, recuperated or in the process of recuperation, Luczinski says, “I already had the perception that there would be better quality water during the dry season.” Now he says he sees the difference “with the naked eye.” He came to have a surplus of grass in the pasture in the rainy season and the production of his property is around 165 kilos per hectare, almost twice the national average of 97.

The restoration that Luczinski achieved is an old dream for the deforested areas all throughout the Amazon. In his inauguration speech, President Lula (PT) reaffirmed the goal of achieving zero deforestation in the region by 2030. On the other hand, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply projects an increase of slaughtered cattle by four million tons over the next ten years, reaching 12 million in 2030. Due to high demand for exports, with China and the United States at the front of the line, there is the expectation of a 17% increase in the total cattle production in the coming decade.

From Brazilian culture to export

After chicken, beef is the meat that is most consumed by Brazilians, bearing significant cultural value, as Lula has expressed on more than one occasion, “the people need to get back to eating barbecue,” an allusion to improvement in purchasing power and economic recovery.

However, it is not only domestic demand that is signaling growth in the coming decade. In 2022, meat exports – including processed products and those in natura – saw a 26% increase in volume compared with the previous year, with 2.34 million tons exported, and 42% growth in revenue, totaling US$13 billion. A combined increase of 30.5% in exports is projected by 2030.

Restoring the pasture, investing in the utilization of the soil’s potential, is the alternative capable of boosting productivity and preventing the deforestation of one million hectares per year until 2030 while attending the market demand for beef production. This figure could come to represent the destruction if productivity in the Amazon does not improve, according to the study published by Imazon, “Policies for developing cattle-raising in the Amazon without deforestation.”

According to data from MapBiomas, the areas designated for grazing occupied 90% of the deforestation in the Amazon – in 2020 and 2021, 26.7 million hectares of forest were lost and, of this total, 23.8 million were turned into pasture. In order to guarantee the two goals – zero deforestation and an increase in meat production -, one possible solution, according to specialists, is by replenishing previously degraded areas in the mold of what is being done by Luczinski in Mato Grosso and enhancing productivity where the forest has been transformed into pasture.

“There has been so much deforestation in Brazil that we don’t need all the deforested area to have good cattle production. If we start investing to improve livestock productivity, there will actually be extra space left over,” says Paulo Barreto, a researcher at Imazon – Instituto do Homem e Meio Ambiente da Amazônia (“The Institute of the Man and Environment of the Amazon”), an organization that is part of the MapBiomas Initiative, developed by a multi-institutional network involving universities, NGOs and technology companies with the intention of annually surveying the coverage and use of land in Brazil and monitoring changes in territory.

Although preliminary data from MapBiomas show a trend of improvement in the quality of the pasture in recent years, 57% of the pasture in the Amazon in 2021 was subject to some type of degradation.

“There has been an improvement, but the percentage of degraded areas is still very high,” says Barreto. The researcher points out that, in order to prevent the expansion of the frontiers of deforestation, it will be necessary to recuperate between 170,000 and 290,000 hectares of pasture every year until 2030, the equivalent of restoring between 0.37% and 0.64% of the existing pastures in the Amazon in 2019, according to a study authored by Barreto and published by Imazon.

More productivity, less deforestation

The Brazilian livestock industry’s productivity is low. In the Amazon, as little as ten animals can be found grazing in areas capable of feeding up to 33. Preventive management, with routine control of the number of animals grazing per pasture area, an annual analysis of the soil, maintaining fertility and controlling weeds, is the most efficient way to prevent pasture from being degraded.

According to the Imazon study, promoting training with continuous technical assistance, providing agricultural credit focused on gains in productivity and installing infrastructure and adequate services are other ways to encourage the more productive use of land.

Moreover, another challenge for the livestock industry in the Amazon is the dry season, which normally lasts from June to October, when there is practically no rain. But, just as with Luczinski, who is in the process of regenerating the forest, it appears that there is a solution: “In 2023, we’re heading into the second harvest year with the consultation and it’s going to be a smooth year during the dry season which is three or four months straight with no rain,” the cattle breeder commemorates. “You need to have your pastures at an elevated level so that the animals don’t suffer during this period,” he adds.

How to evaluate degraded pasture

According to Embrapa – Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (“The Brazilian Company of Livestock Research”), one way to evaluate whether pasture is in the process of degradation is to track its capacity for support, in other words, the number of animals that it is possible to maintain on the grass without losing weight or a reduction in milk production. If there is a need to reduce the amount of cattle in the area, then this points to a probability of the pasture being in a process of degradation. An increase in weeds, a decrease in the percentage of grass and an expansion of uncovered ground – which facilitates erosion, the loss of organic substance and nutrients – are also indicators.

The degradation of pasture is one of the factors that lead to the opening of new fronts of deforestation – cattle-raisers opt for clearing areas rather than recuperating the land they have already occupied. However, programs that make it easier to regularize illegal land possession, promoted by the federal and state governments, end up encouraging speculative occupations. “The livestock industry is always going to look for new frontiers and this is possible because of the culture of land-grabbing: Illegal occupation of public lands by way of falsified documents,” Barreto says.

The livestock industry is always going to look for new frontiers and this is possible because of the culture of land-grabbing.

Paulo Barreto, researcher at Imazon

CAR – Cadastro Ambiental Rural: The Rural Environmental Registry, a mandatory electronic registry effected by self-declaration whose purpose is the environmental regularization of rural properties throughout the entire country is one of the devices that has come to be misused by land-grabbers who register portions of public lands as their private property. Next, they cut down the forest and transform it into pasture to characterize productivity. The real estate market only values the forest once it’s cleared. According to IPAM – Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (“The Institute of Environmental Research of the Amazon”), there are over 100,000 illegally declared properties on public forests as if they were privately owned.

“Criminal activity has begun operating on such a large scale that it generates an entire economy. Cities are highly dependent on it. You have the illegal land-grabbing, then you have all the commerce and the gas station,” explains Barreto, remembering that crime has become more structured and heavily armed in recent years, in addition to gaining a certain social legitimacy.

As such, combating deforestation will also require, according to the Imazon study, heightened oversight, the designation of public lands for uses that are compatible with forest conservation, an increased transparency of information to strengthen private initiatives to combat deforestation and an expansion of payments for forest conservation.

For example, the project Conserv, a private payment mechanism for environmental service implemented by IPAM in late 2020, financially compensated 41 rural producers in the Amazon who protect areas of native vegetation larger than the Legal Reserve on their properties. Contracts in Mato Grosso and Pará protect about 15,000 hectares of forest.

According to Barreto, it is a fallacy to say that combating deforestation will slow down development. On the contrary, having the forest intact stimulates increased production, precisely because there are rural areas that are less utilized. Moreover, there are financial rewards for restoring pasture. The Imazon study also shows that the total investment to increase production by renovating pastures would be the equivalent of between 28% and 53% of the cost of deforesting, depending on what the restoration requires. In other words, deforesting can be up to 70% more expensive than restoring.

Report from InfoAmazonia for the project PlenaMata.