A MapBiomas study released at COP27 on changes in land use in threatened South American ecosystems found that expanding farming and cattle raising activities were drivers for the loss of Amazonian forests between 1985 and 2020.

Over 31 billion tons of CO2 equivalent were released into the atmosphere by deforestation activities inside the Brazilian Legal Amazon between 1985 and 2020. The volume represents nearly 70% of all emissions caused by the loss of forests in all of Pan-Amazonia over the period.

Territories of nine different countries compose the part of Amazonia where deforestation was responsible for the emission of 45.1 billion tons of greenhouse gases over the last three and a half decades. These were the findings of a MapBiomas study on land use conversions in threatened ecosystems released at the 27th UN Conference on Climate Change (COP 27).

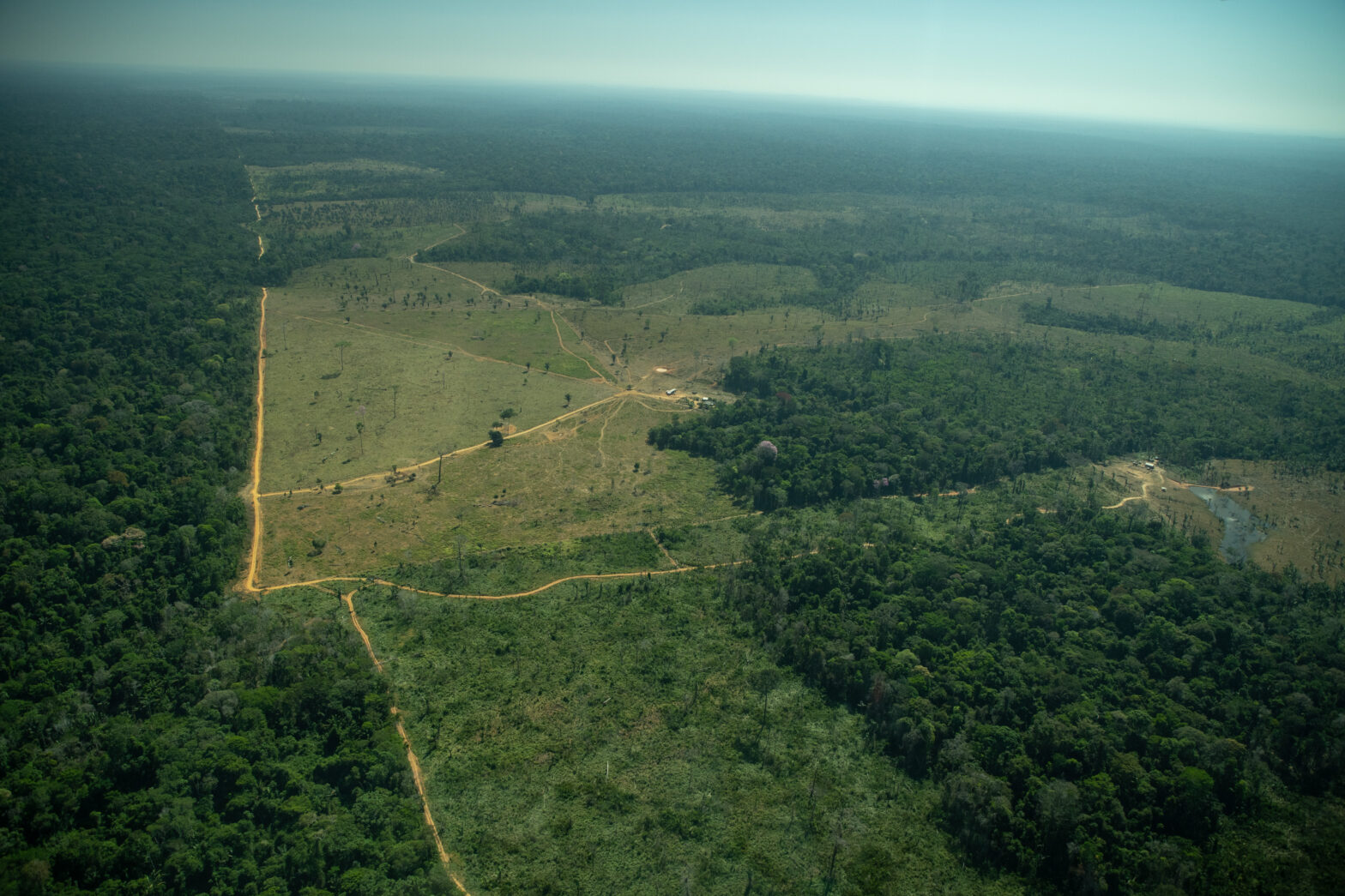

In this period, Pan-Amazonia lost 75 million hectares (Mha) of native vegetation, or 9.6% of its territory. It is an area nearly the size of Chile. Forests were the most affected, with 58.4 Mha of lost area. Savannas and natural non-forest formations were also impacted by human activities inside South America’s largest biome.

Pan-Amazonia lost 75 million hectares (Mha) of native vegetation, or 9.6% of its territory. It is an area nearly the size of Chile. Forests were the most affected, with 58.4 Mha of lost area.

In 1985, 92% of Amazonia was still covered with native vegetation. By 2020, this cover had fallen to 83%. The loss of 9.6% over these 35 years was greater than all the area lost in the 500 years since the continent was colonized by Europeans.

Brazil’s territory encompasses 62% of Pan-Amazonia and it was here that 81% of the lost vegetation once stood. The study also warns that the current percentage of vegetation left in Amazonia (83%) is nearing the point of no return, when the forest loses its natural ability to regenerate itself. “If we continue destroying vegetation the way we are, we may hit the tipping point during this decade. If that happens, Earth’s largest tropical rainforest will be transformed into a generator of greenhouse gases,” affirms Julia Shimbo, scientific coordinator of MapBiomas in Brazil.

If we continue destroying vegetation the way we are, we may hit the tipping point during this decade.

Julia Shimbo, scientific coordinator of MapBiomas in Brazil

According to Luciana Gatti, researcher at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) the spread of deforestation, wildfires and cattle raising in the region has made it so that Amazonia releases more greenhouse gases (GHGs) than it can absorb. In 2021, for example, the Brazilian Amazon managed only to capture less than half of its emissions, leaving a surplus of 740 million tons of CO2 equivalent (42% of Brazil’s net emissions), according to the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimate System (SEEG).

Gatti explains that deforestation inhibits the formation of rain clouds in Amazonia, making many regions of the biome hotter and drier, which kills trees and consequently increases emissions, creating an avalanche effect.

“The Amazon Rainforest works like a shield against climate change because it produces much rain, cools things down and absorbs carbon. But when trees are cut down, we transform Amazonia into an accelerator of these changes. The most devastated regions of the biome, like the southeast, are those that have lost the most rainfall in the dry season, which has become hotter and lasts longer”, affirms Gatti, who holds a PhD in Chemistry.

The Amazon Rainforest works like a shield against climate change because it produces much rain, cools things down and absorbs carbon. But when trees are cut down, we transform Amazonia into an accelerator of these changes.

Luciana Gatti, researcher at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research

Brazil leads in Amazonian devastation

Between 1985 and 2020 there were 60.6 million hectares (Mha) of vegetation lost in the Brazilian Amazon, nearly 13% of the nation’s part of the biome. When only the forests are analyzed—leaving savannas and other non-forested natural formations—the loss was 58 Mha. In 1985, 84% of the Brazilian Amazon was covered in standing forest, compared to 73% in 2020.

Farming and cattle raising were the main causes of deforestation in Brazil. According to the report, in the mid-1980s, there were 38 Mha of land dedicated to farming and pastureland in the Brazilian Amazon. Thirty-five years later, this area had more than doubled (a 157% increase), currently covering 98 Mha of the biome.

The study shows that over 80% of all land dedicated to farming and cattle raising in Pan-Amazonia in 2020 was located in Brazil.

According to Julia Shimbo, many factors explain the country’s role in the devastation in Amazonia. “First, because we have a larger portion of the biome than the other South-American nations. Second, there is an historical factor of expansion and transformation of large swaths of forest into farmland because of environmental and climatic condition, but also because of economic and political scenarios.”

She refers to the recent weakening of the federal monitoring and control agencies as a major factor in increasing pressure on the forest, especially in regions that had, until recently, been relatively well-preserved, like southern Amazonas State and the adjacent regions.

“It is important to remember that there are also cultural factors. The agriculture here is different than that found in other countries and the strength of cattle farming in Brazil is also part of this. Another question is the land issue, which still stands to be resolved. In order to keep the rainforest standing, dealing with this question is essential so that areas can be legally protected”, she adds.

The relationship between deforestation, cattle raising and CO2 emissions

Despite the fact that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon was reduced by 70% between 2002 and 2011 arriving at stable indices by 2017, the devastation has been increasing considerably in recent years. In 2020, nearly 1/5 of all clearcutting in the biome was perpetrated in only three municipalities in the Amazon. Altamira (PA), São Félix do Xingu (PA) and Porto Velho (RO) held the first three spots in the regional ranking for deforestation that year according to the ground use data from MapBiomas.

Farming and cattle raising were the main drivers for the devastation in these municipalities, causing 99.7% of the logging. São Félix do Xingu and Porto Velho were home to the largest cattle herds in their respective states in 2020, while Altamira ranked fourth in number of head of cattle in the state of Pará, according to data from the IBGE’s Municipal Farming and Cattle Raising Study.

These municipalities also head the list of the biggest CO2 equivalent producers in all of Pan-Amazonia from 1985-2020, according to the MapBiomas analysis. The three cities spewed over 2.1 billion gross tons of carbon equivalent into the atmosphere, considering the loss of native vegetation alone.

Luciana Gattie explains the relationship between farming and cattle raising, the destruction of natural vegetation and the release of GHGs. “Raising cattle requires vast areas of land. Soybean and corn monocultures for animal feed are also a part of this process. All this translates into cutting down trees which, in turn, increases emissions. In other words, the production of beef generates an enormous imbalance for the planet.”

Julia Shimbo believes that it’s vital for Brazil to find ways of creating value for standing forest that bring concrete economic benefits in order to overcome the need for large-scale cattle operations and monoculture farms.

“We are experiencing a climatic emergency today where temperatures are rising and precipitation patterns are changing because of deforestation. All this will, on the long term, undermine farming itself, which depends on climate stability to work. In other words, agribusiness needs the rainforest”, concludes Shimbo.