Research shows that forest clearing reduced water flow and power generation in hydroelectric plants in the Center-West and Southeast of the country. Despite the environmental and electricity bill impacts, the government wants new power plants and dams on the Tapajós River.

Amazon deforestation reduced rainfall and generation in hydroelectric plants in central Brazil and increased the electricity bill due to the use of thermoelectric natural gas plants. This is what a study by the Brazilian environmental engineer Fernanda Massaro Leonardis concluded, guided by scientists from the universities of São Paulo (USP) and Porto (Portugal).

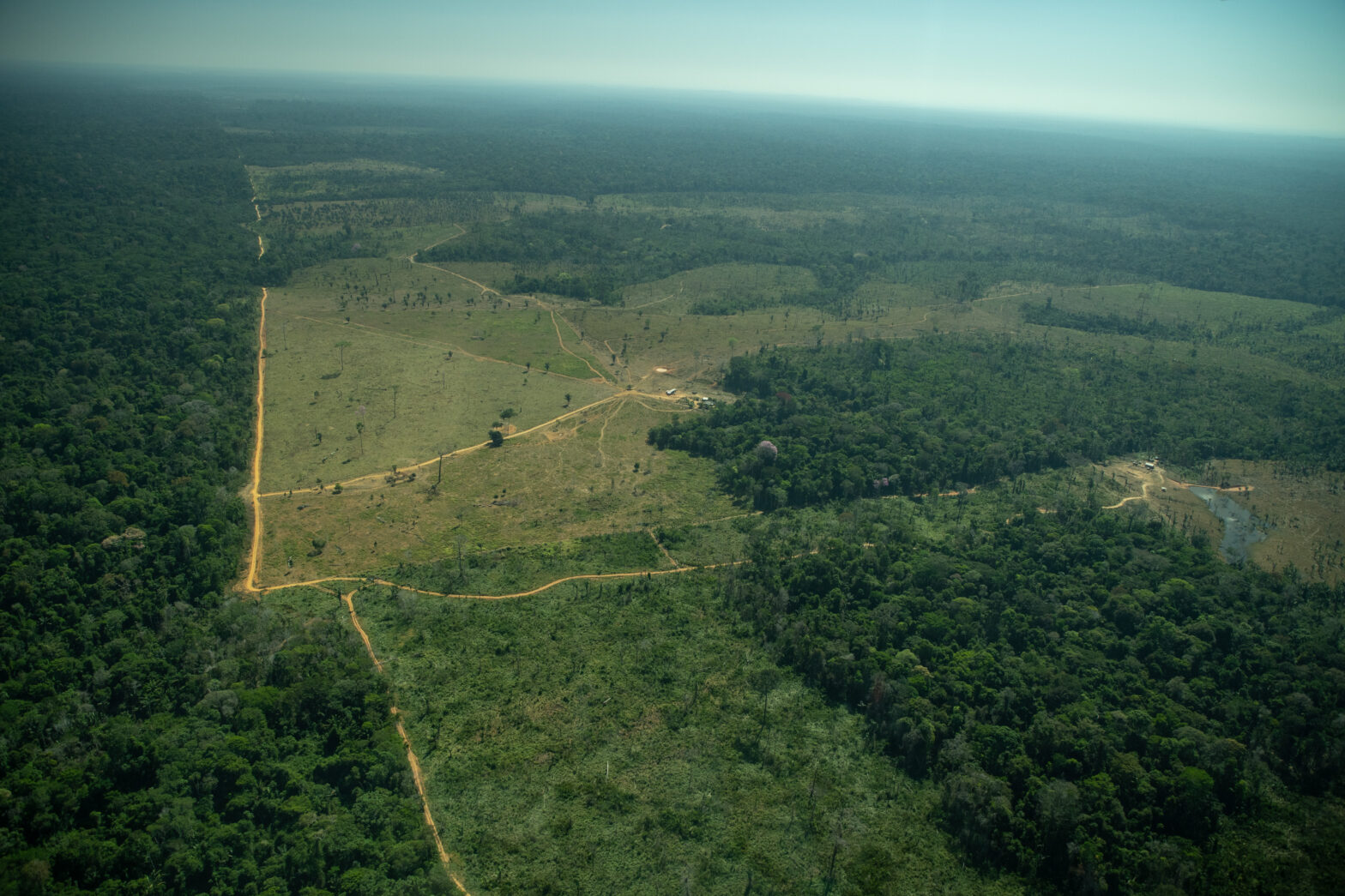

The Amazon has lost 730,000 km² since 1988, or 17% of the biome, according to the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe). The area is equivalent to almost three times that of the state of São Paulo. In a decline until 2012, deforestation grew in the following years and has been breaking record after record in the Bolsonaro government. In 2021, 13.2 thousand km² were destroyed, 22% more than in the previous year and the highest rate since 2006.

With the shrinking vegetation, winds blowing from the Atlantic carry less moisture released by the forest into the atmosphere of Brazil and neighboring countries, weakening the so-called “flying rivers”. As this “rain factory” dwindles, the lack of water for agriculture, industry, and power generation grows. Phenomena such as El Niño and La Niña and deforestation in other biomes also influence rains and droughts in South America.

Water scarcity reduced energy production in the 11 plants chosen for the study: Mascarenhas de Moraes, Furnas, Água Vermelha, Marimbondo, Três Marias, Serra da Mesa, Emborcação, Nova Ponte, Itumbiara, Corumbá, and Queimado. They account for 70% of the generation in the Center-West and Southeast subsystems. As they are close to the headwaters of the rivers, the level of their reservoirs depends mainly on the rains reinforced by the humidity of the Amazon.

“I analyzed these plants because they are directly influenced by the ‘flying rivers’ and are not affected by water from other dams to produce electricity,” the researcher explained.

The effects of deforestation in the Amazon are cumulative and, if it is not stopped, the situation will become worse for energy generation and other sectors in the country.

Fernanda Leonardis, environmental engineer

Her work shows that the average flow in these hydroelectric plants shrank 37% from 2013 to 2021, plummeting from 98.5 thousand cubic meters per second to 63 thousand cubic meters per second. At the time, deforestation in the Amazon was growing, and the plants used more water for the reduction of residential and industrial tariffs decreed by the Dilma Rousseff government. The level of the dams has not recovered since then.

The national energy demand has been growing since the early 2000s, shortly after the “Blackout” that left much of the country without energy. At the time, almost 90% of national electricity came from hydroelectric plants. The rate is now 64%, as shown by InfoAmazonia. The remainder is supplied by wind, solar, and nuclear sources, but above all by gas-fired thermoelectric plants, which increase the economic and environmental impacts.

Estimates from the Institute of Energy and Environment (Iema) show that carbon dioxide emissions, a pollutant that increases the global climate crisis, grew 121% from 2020 to 2021 in Brazil due to the burning of fossil fuels in thermoelectric power plants. The plants were activated to compensate for the drop in hydroelectric generation because of the lack of water. Brazilians’ monthly electricity bill is also impacted. The lack of rain and the activation of thermal plants have caused monthly household spending on energy to grow 114% since 2015, according to the balance sheet of the Brazilian Association of Electricity Wholesalers (Abraceel).

“The government decision to expand investments in thermoelectric plants reduces the space for growth of solar and wind sources, faster and cheaper to install and with less socio-environmental impacts. It also makes the national energy matrix more dependent on fossil fuels, ”said Ricardo Baitelo, Iema’s Project Manager.

But the reduction of rainfall and flow in hydroelectric plants related to deforestation did not sensitize the government to abandon these impactful projects. A “jabuti” – a clause inserted into a bill about another subject – inserted in the privatization of Eletrobras wants to expand the use of natural gas in the country and threatens the Amazon rainforest with more deforestation, including in protected areas, according to a report by InfoAmazonia. In January, the Bolsonaro administration signed a law guaranteeing mineral coal power generation contracts until 2040.

Given this scenario, Baitelo evaluates that the country needs to decentralize and diversify its electricity sources to ensure sustainable economic development with less impact on people and natural environments.

“Producing energy with solar, biomass, or biogas can supply cities as well as rural and isolated populations, heat other economies, and reduce dependence on large hydroelectric plants placed far from consumers, in the Amazon and the rest of the country. We also need to invest more in the efficiency of domestic and industrial equipment,” he highlighted.

This month, the National Electric Energy Agency (Aneel) extended the deadline for studies on technical and economic issues related to the construction of the Jamanxim (881,000 kW), Cachoeira do Caí (802,000 kW), and Cachoeira dos Patos (528,000 kW) plants in the Amazon until 2023. According to state-owned companies, they could provide electricity to 5.5 million homes.

The hydroelectric plants will be located in the Tapajós Basin, where deforestation and contamination of land, water, and populations by mercury from gold mines are on the rise. Its construction contradicts the trend that the Amazon should no longer house large power plants due to their excessive socio-environmental impacts, such as in the case of Belo Monte.

A report by indigenous and environmental entities presented last October points out that the projects of 43 hydroelectric plants, dams, highways, and ports in the region will especially benefit the production and export of soybeans, meat, and other commodities at the expense of the destruction of the rainforest and its populations.

The document calls for the Brazilian State to comply “fully with national and international laws and standards regarding the rights of indigenous peoples” and for companies to consider “the environmental and social impacts in risk analysis and to align their due diligence to national and international human rights norms and standards.”

“Projects such as the power plants in the Tapajós were archived for their impacts and make little sense in the face of the economic and climate crises, which call for a safer and more resilient matrix. Companies are abandoning these projects in Brazil and around the world, including commitments to reduce deforestation and contain climate change,” said Ricardo Baitelo, Iema’s manager.

The Ministry of Mines and Energy did not respond to requests for an interview.

Reporting by InfoAmazonia for the PlenaMata project.