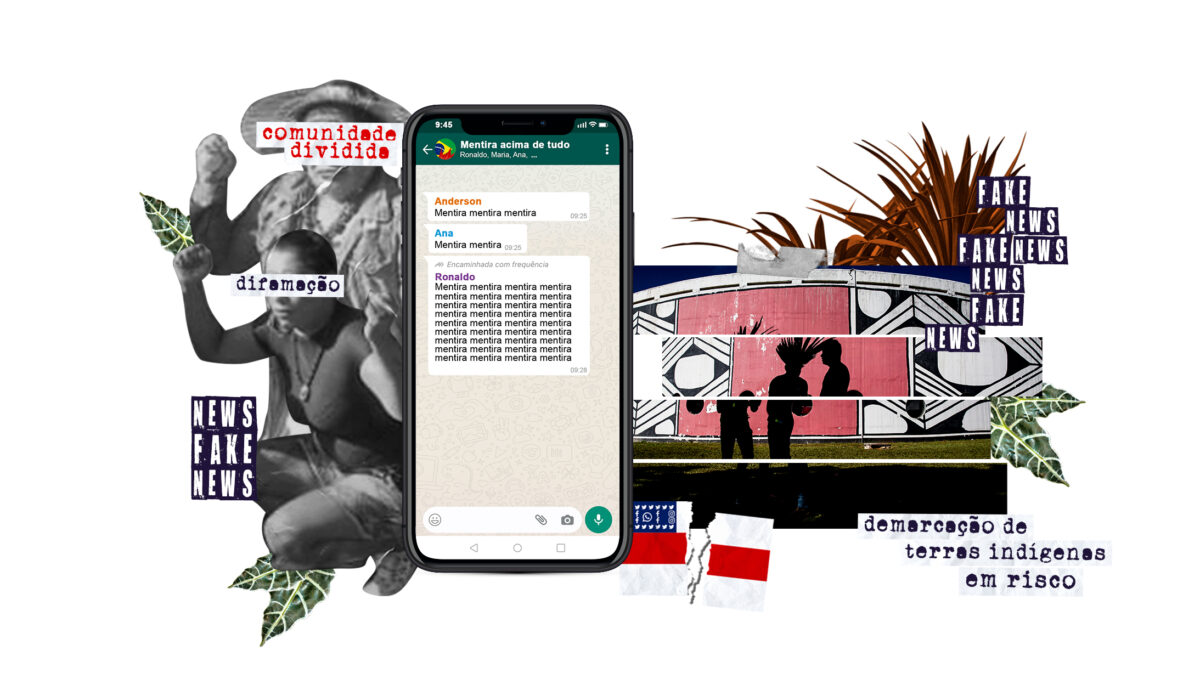

Under one of the tents set up in Brasília (Federal District) at the largest Indigenous encampment in the history of the Brazilian democracy, Chief Agnelo Xavante, 52 years old, of the Etewawe Indigenous Land (Mato Grosso), took the microphone and, for a moment, stopped the protest. Visibly dismayed on that day in September 2021, the leader asked for the attention of the nearly 6,000 Indigenous people present. He needed to refute a video shared in WhatsApp groups that affected everyone there. The integrity and national representation of the Indigenous organizations on the front lines of the movement were being targeted.

The post had reached Indigenous groups from across the country on the app, said Agnelo. But not just them. The content had already circulated on WhatsApp among other public groups in Amazonas state. These groups have interests ranging from politics to religion, and have been monitored since August for the report Amazonas—Lies have a Price. “The video has reached a lot of WhatsApp groups. That hurt us. Do you know that there are 320 upset Xavante villages? This has never happened before. I, a Xavante warrior, cannot hear this and stay silent.”

With the microphone in his hands, Agnelo defended the base organizations, “the voices of the Indigenous peoples in Brazil,” and shared a new video among his contact networks, refuting the previous one that had baselessly accused the Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) and the Coordination of the Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB) of using the encampment’s resources for other purposes and stated that the organizations do not represent the Indigenous communities of the entire country.

The mobilization happened during the Federal Supreme Court (STF) hearing on the ancestral land time limit, a legal opinion that states that Indigenous people should only have the right to their land if they were occupying it in 1988, the year the new Brazilian constitution was enacted. “The demarcation of Indigenous lands doesn’t concern many, that’s why they recorded these lying videos. Our conflict and our division is what they want,” says Agnelo. The hearing was stayed after a request for examination by Justice Alexandre de Moraes, who wanted more time to analyze the case.

While Agnelo recorded the video, Chief Eronilde Fermin Omágua of the Kambeba people of São Paulo de Olivença (Amazonas), who was also at the national demonstration, needed to defend herself against hate messages shared on social networks.

“Someone posted two audio messages against me in a WhatsApp group with over 300 women in Amazonas, saying that I wasn’t fighting for collective rights, that I wasn’t committed to the cause and that I didn’t represent my people. All the rights conquered by the Kambeba are the fruit of a tough fight of many years. But with this fake news about me, I’ve stopped being seen as a fighter and became a villain. I am attacked day and night and this has hurt my family,” she states. Eronilde says she doesn’t know the Indigenous woman who accused her.

People who weren’t in Brasília were also the target of attacks. Milena Mura, a leader of the Mura people (Amazonas), was a victim of lies on WhatsApp and social networks. While she and 400 other people from 17 communities protested on state highway M254, which connects Manaus (the capital of Amazonas state) to Porto Velho (the capital of Rondônia state), against the cut-off date, inaccurate stories were being shared.

“We were fighting for our rights, however, they started spreading on the social networks that we were looking for political squabbles, that we wanted to start a riot and we were harming business and health because of the COVID-19 pandemic. With this, even other villages started attacking our organization, questioning the goals of our movement,” she says. According to Milena Mura, the Mura Indigenous Council had to convene an extraordinary meeting and summon the leaders of 34 villages to refute the fake news.

“Disinformation is a strategy. In the case of the Indigenous peoples, it is to get access to the land, natural resources and the areas that are constitutionally protected to be public and to respect the historic presence of the Indigenous peoples,” states Denise Dora, the executive director of the organization Artigo 19 in Brazil and South America.

The fake news regarding Indigenous leaders, she adds, has a powerful impact on the community. “The damage that lies cause to a leader is like a light rain. It’s hard to catch, since it falls in many places and you don’t know where it will strike those people next. And the reputation you took years to build up. A credibility crisis creates extra confusion.”

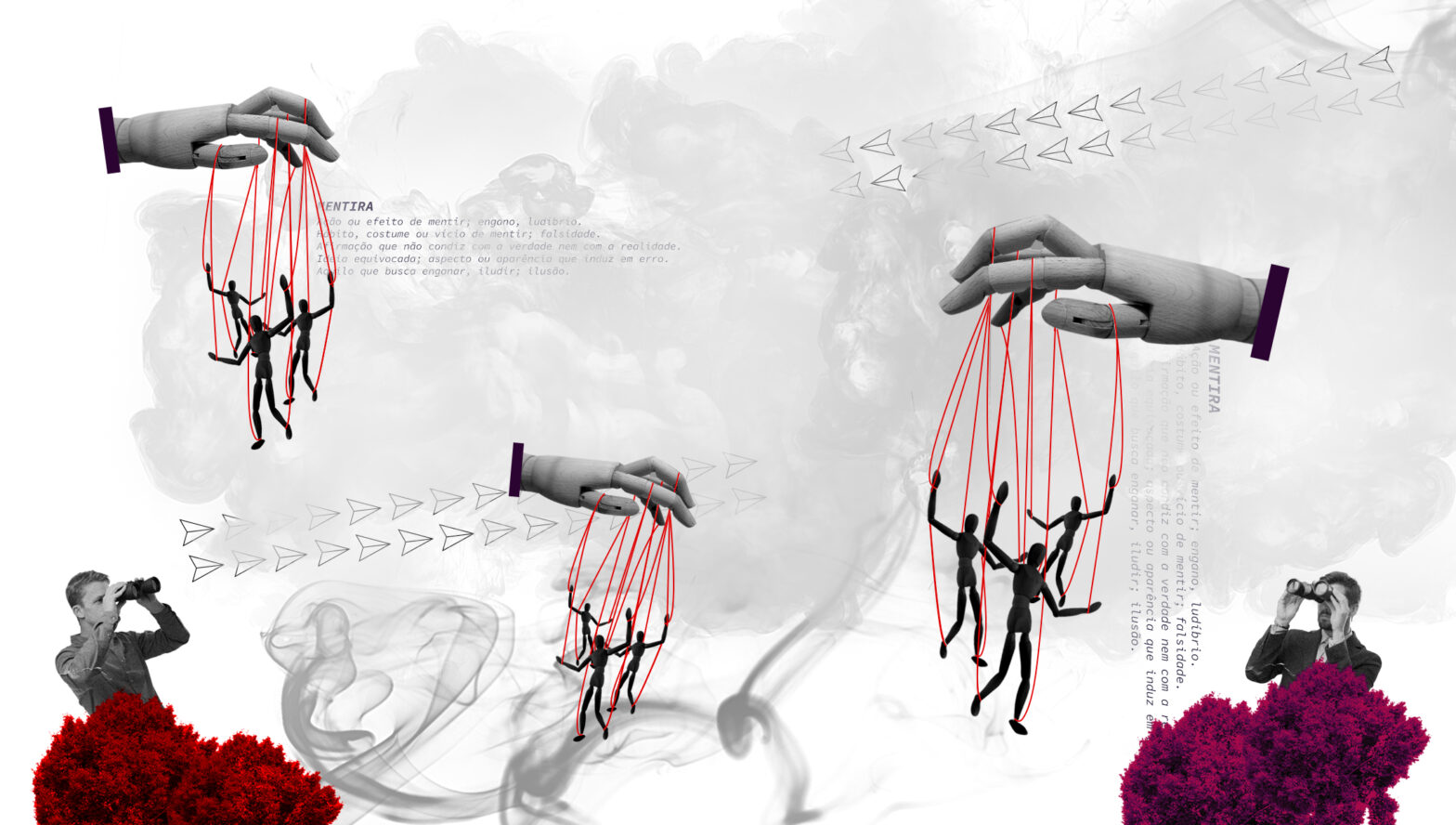

In the 11 public groups in Amazonas monitored by the report, stories attacking the movement against the ancestral land deadline were also shared. One of them broadly credited the protests to NGOs and leftist parties. Others associated the movement with violent acts and “vandalism”—like one accusation published on the site Direto ao Ponto.

When contacted for this report, the site sent a note that stated that it “not only respects but also recognizes and supports the fights for the Indigenous cause, above all regarding the preservation of their culture and sustainable use of their lands. As a communication outlet that creates informative and opinionated content, it cannot avoid, however, criticizing protests of any nature that steal from the public heritage and threaten the life of citizens as does, regrettably, the case in question.”

“Demarcation of Indigenous lands: Agro requests respect for the Constitution” was another post circulated in groups. The content shows the position of the Agricultural Parliamentary Front (FPA), which is in favor of the ancestral land time limit. The post says that “the FPA clarified that it is not ‘against Indigenous rights,’” however, it defends the “right to property and fair compensation for the rural property owners who have their lands demarcated.” This same post was published on the site Terra Brasil Notícias, in the magazine Revista Oeste and on the site Folha Livre. The media outlets were sought for comment, but none responded before publication date.

Professor Leda Gitahy, of the Department of Political Science and Technology at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp) and one of the coordinators of the Disinformation on Social Networks Study Group, says that there is an ecosystem that carefully organizes disinformation strategies and political propaganda to divide communities.

“The problem is the same across the whole country. The logistics behind this is to release messages that spread quickly to cause confusion and doubt. All disinformation is based on something real. The strategy of the lies shared in WhatsApp groups is to make the Indigenous peoples fight amongst their own people to break down the movement. They need to divide the Indigenous peoples so they don’t resist like they are [currently] resisting. And these populations resist because they are constantly attacked,” says Gitahy. In the Bolsonaro administration, no Indigenous land was demarcated.

When lies cause avoidable deaths in communities

The study group coordinated by Leda at Unicamp was formed last year to investigate false information surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, including denialist narratives of the disease, critiques of the vaccine and miraculous cures. Reports from the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI) and APIB highlight that 2020 was marked by a high number of Indigenous deaths that occurred as a result of the mismanagement in the fight against the pandemic in Brazil, based on disinformation and government negligence. “The federal government is the main transmitter of the virus among Indigenous peoples,” says the APIB report.

“Fake news says that the vaccine was from the devil, that it implants a chip, anything so that people wouldn’t get vaccinated. And we’ve had resistance from within the territory: at an area of the river where there are over 1,000 residents, only 160 wanted to take the vaccine at one point,” said Marivaldo Baré, the president of the Federation of the Rio Negro Indigenas Organizations (FOIRN) in Amazonas state.

According to Baré, the federal government did not promote any public information campaigns about the vaccine to combat the disinformation strategy that hit the villages of the upper Rio Negro. On the contrary, the president’s public disbelief in the vaccines helped to worsen the situation. “For us, fake news was an aggravating factor during the pandemic. We had to work hard to produce, on our own, audio messages and pamphlets talking about the importance of vaccination and prevention to avoid contamination, because there was never any government support.”

Vanda Ortega Witoto, who is Indigenous and a nursing assistant, was a victim of defamation and racism in public WhatsApp groups and on social networks for making history as the first person in Amazonas to be vaccinated against COVID-19, in January 2021.

“I spent all of 2020 in this fight asking for help and attention for our community because of the COVID-19 pandemic. I thought about turning down the invitation to be the first person vaccinated, but that was an opportunity to give a voice to the Indigenous people in the city who weren’t a priority in the vaccination plans at that time. I accepted because it was a political act of resistance,” she says. It had a price.

Soon lying videos and photos questioning Vanda’s identity started spreading in WhatsApp groups and on social networks. “They said that I was a ‘fake Indian’ because I don’t wear traditional clothes and I live in the city instead of the village. They say that they should vaccinate real Indians and not me. They called me an opportunist. That went viral, and I got innumerable hate messages. It was horrible.”

She reacted and posted a video. “I didn’t fight back with the same hate speech. What I did was show our struggle because there is still a lot of prejudice against Indigenous peoples. We are invisible to society. We are constantly the victims of news that destroys our communities.”

The false content, says Francesc Comelles, the regional coordinator at CIMI, started having a larger impact on Indigenous communities as internet access within the territories increased. On the one hand, technology connected leaders and allowed them to quickly report violations; on the other, it exposed everyone to fake news.

“This mixture of true information with a mix of twisted and malicious information was compounded with the fake news surrounding the pandemic, which had a direct impact on the health of the Indigenous people,” he says, highlighting that the division in the community hindered the fight for public policies.

Whoever is the target of untrue content spread on social media should seek out support. According to Dora, the search for help should always be done through the majority organization in the region, the Association of Indigenous Peoples (APIB), the Coordination of of Indigenous Organizations in the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB), the Federal Public Defender’s Office, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), human rights groups and civic organizations. “It’s necessary to seek help to turn it around. And there are ways to do that,” she added.

In a note, COIAB stated that the indigenous victims of lies should evaluate if the reach and impact of this action can, in some way, harm or cause unjust damages directly to their person. If so, they should seek out the police and “their regional organization in order to publicize the occurrence and seek support.”

The Other Side

The Ministry of Health was contacted via their press officer to comment on the aspects mentioned by APIB and FOIRN, but it did not respond by the time of publication. When asked about actions to support the Indigenous peoples, the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) said in a note from the press officer that “instead of working with false statements, it has been acting effectively with practical measures to support the Indigenous population, for example, the investment of around R$34 million to monitor Indigenous Lands across the country in 2021.”

The Escalation of Violence Against Indigenous Communities in Brazil

Follow those who are on the frontlines of reporting violence against the Indigenous peoples in Brazil:

The Observatory of Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil: A project of the Indigenous Missionary Council, responsible for annual reports. The most recent, with data from 2020, showed an explosion of conflicts and murders of Indigenous people. Download it for free here (portuguese).

COVID-19 Monitor: To combat the underreporting of COVID among the Indigenous populations, the Socio-environmental Institute and the Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil launched a monitor for cases of the disease. The data is here.

Mídia Índia (Indigenous Media): Independent collective of Indigenous communicators, with representatives from various communities and regions of the country, that reports violations and threats. They also report victories by relatives in the fight for justice, identity and territory rights. See: midiaindia.org

Veja também

Bombou no YouTube: o “novo índio” e a “nova Funai” de Jair Bolsonaro

Filme negacionista é um dos vídeos mais compartilhados no Telegram

A falácia da soberania nacional na Amazônia, segundo Izabella Teixeira