The story of a Brazil that protects and preserves the Amazon is the 10th most-shared video in far-right groups and channels on Telegram (a messaging service that is a competitor of WhatsApp). The problem is that this story does not match reality.

Released in July, the film Cortina de Fumaça (“Smokescreen”), which contains denialist content about deforestation, rapidly climbed the ranks of the most-shared YouTube links on Telegram, according to a study that analyzed the posts from January to October 2021.

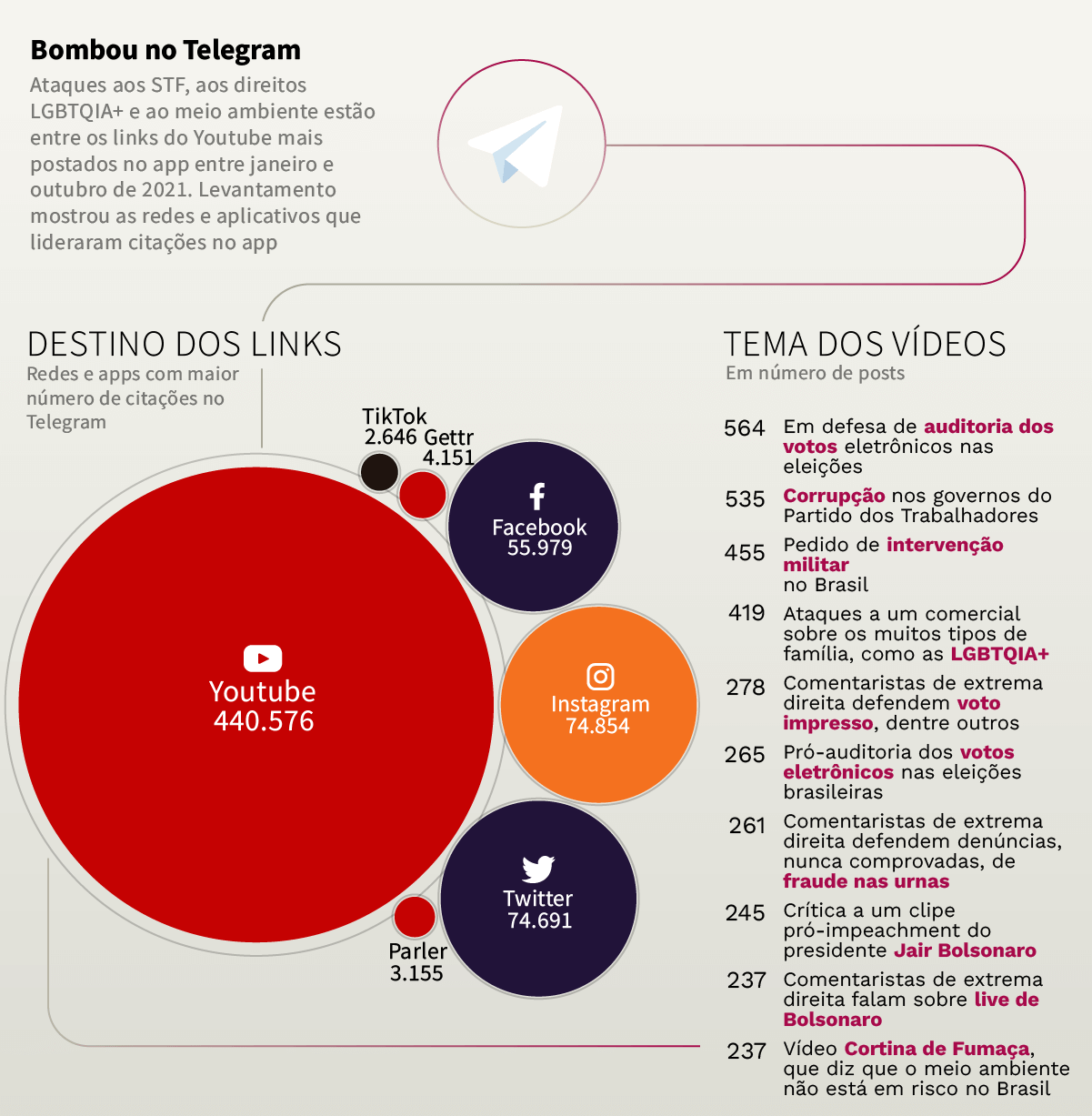

There were 237 posts about the film produced by Brasil Paralelo, with over 2.5 million views on YouTube, during a year that Brazil broke the third consecutive record for deforestation in the Amazon. When contacted for this report, the production company denied that it shares inaccurate information (hear from the other side below).

“We noticed that environmental subjects matter to these groups when it is linked to political issues, like the upsurge of deforestation in the Amazon, a crisis for the Bolsonaro administration,” says Leonardo Nascimento, one of the coordinators of the study.

The Telegram mapping was done in partnership with professors Paulo Fonseca of the Laboratory of Digital Humanities at the Federal University of Bahia and Letícia Cesarino of the post-graduate program in social anthropology at the Federal University of Santa Catarina. Together they won a grant for disinformation research, promoted by InternetLab.

The study analyzed around 4 million messages transmitted on Telegram between January and October 2021 in 42 groups and 108 channels connected to the far-right, with 277,000 and 3.3 million users, respectively.

Created in 2013, the app arrived in Brazil in 2016. Telegram achieved the rank of fastest growing mobile messenger app in 2021. The app lacks content moderation, and groups can have up to 200,000 people—a differentiator compared to the 256 participant limit on WhatsApp. Channels do not have a limit on their size: President Jair Bolsonaro’s group has over 1 million subscribers. Telegram did not return requests for an interview to explain if it has adopted tools to control disinformation.

The report had access to a few hundred messages about the subject of socio-environmentalism. An unwary user of the app might believe that the current government has reduced illegal deforestation by 70% and protects Yanomami rights, in spite of reports that show families who are sick and starving and the surge in illegal mining in Indigenous territory.

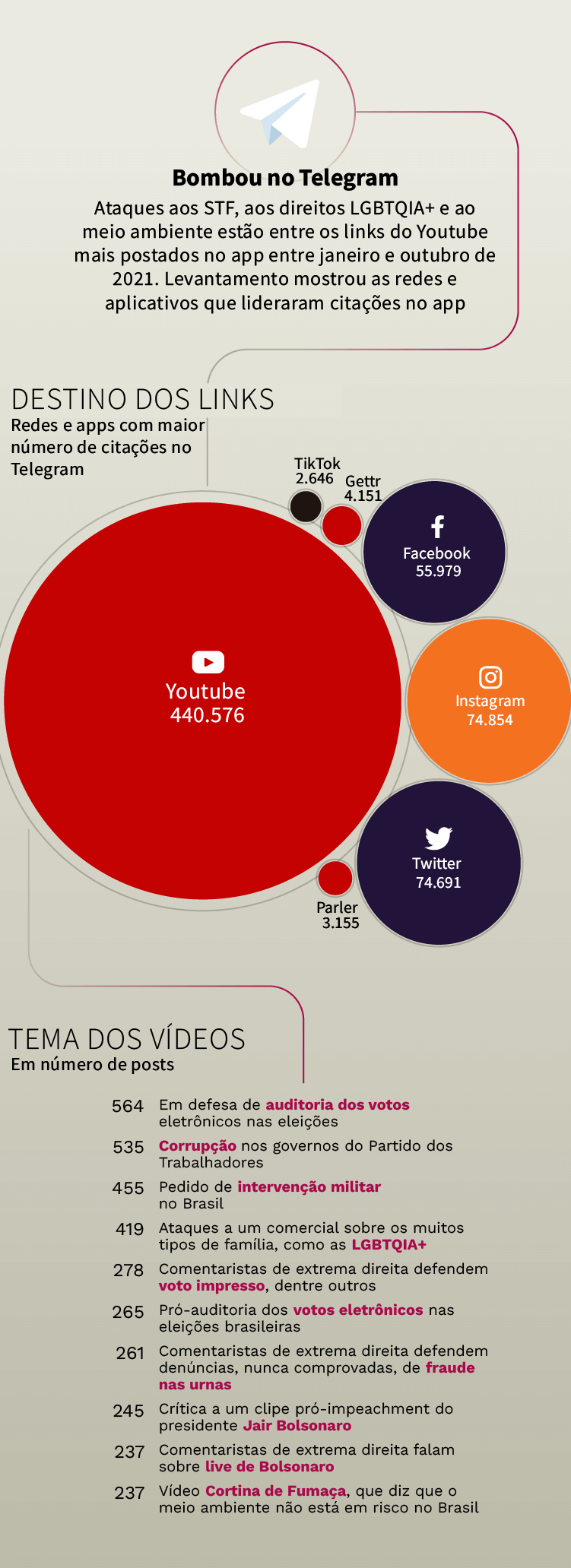

One of the conclusions of the study, says Nascimento, is that Telegram works like a driver for far-right channels on YouTube, which remunerates content producers. The study showed that YouTube is the ecosystem with the most citations on Telegram with 440,576, followed by Instagram and Twitter, with 74,854 and 74,691, respectively.

“You can’t understand Telegram without understanding the other platforms, and vice versa”

Leonardo Nascimento, one of the coordinators of the study

The analysis of messages shared in public groups, however, pointed to a larger problem, showing that the app is used to distribute lies. “You can’t understand Telegram without understanding the other platforms, and vice versa,” says Nascimento.

In December 2021, the president of Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court (TSE), Minister Luís Roberto Barroso, stated: “It is through Telegram that many conspiracy theories and false information about the electoral system are being disseminated without any control.” As the study from the researchers shows, the theories don’t stop at the ballot boxes.

In an interview for the project Amazonas: Lies Have a Price, Nascimento talks about a multiplatform disinformation ecosystem, revealing the “face” of the false content and conspiracy theories on Telegram and YouTube’s role. Check out the highlights from the conversation:

InfoAmazonia – The initial study was focused on interactions on the Telegram app, but the final report included other platforms. Why?

Leonardo Nascimento – From the analysis of messages shared in public groups on Telegram, we noticed that you can’t understand Telegram without understanding the other platforms and vice versa. It doesn’t matter if you look at and sort out one of them, because it’s not going to work. This was one of our discoveries, which we call a “multiplatform disinformation ecosystem.” For example: unlisted videos on YouTube, which you don’t find in search results, are shared in messages on the apps. It is a gigantic problem and hard to solve, and we are trying to find solutions. Starting with Telegram, we want to understand each of the most well-known platforms, like Instagram and WhatsApp, and new ones like Gettr and Parler.

What did you find on Telegram?

Between January and October [2021], we noticed an exponential increase in the number of user groups and channels, as if they were revving the engines for next year’s elections. Our initial hypothesis is that the majority are not bots, but are people connected in clusters. If 2020 was the year of chloroquine and early treatment, which are not based on science, in 2021 this subject died and a new one appeared—anti-vaccination. We also did a detailed analysis of the first two weeks of September [when the antidemocratic acts against the supreme court occurred], when they demanded that the Federal Supreme Court (STF) be closed. We created a computational collection framework to analyze the images, 2,500 in total. Our team did not have access to the people’s data; we hid the user information and transformed them into a code so that nobody could be identified. This is important for both the user and the researcher.

What kind of user shares the most?

We created a term for this type of user: talkative. The numbers are shocking. There is one individual who spends the entire day posting, from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. One person sends 600 to 1,000 messages per day. In the next stage of the study, we want to understand the extent of these people’s actions.

What content goes viral on Telegram?

On the list of the top 10 most-shared videos, there is anything from attacks on the Federal Supreme Court to the documentary Cortina de Fumaça (Smokescreen) [produced by Brasil Paralelo]. This last one really caught our attention. Environmental subjects matter to these groups when it is linked to political issues, like the upsurge of deforestation in the Amazon during the Bolsonaro administration.

With the data that the team collected, is it possible to say that a platform or network is the key player?

YouTube, without a doubt, is the key player in disinformation. From January to October of [2021], there were over 400,000 YouTube links shared in these groups. In an analogy to drug trafficking, it’s like the apps are the message runners (“aviõezinhos”) and YouTube is the crack house. The center of production is YouTube and to run the logistics of these industrial disinformation products, they enter the networks and the apps.

Why YouTube?

We have two hypotheses to explain this situation in Brazil. The first is that the remuneration that others either don’t have or offer a lesser amount. So we need to follow the money to understand this mechanism, and we know very little about this disinformation industry. Where is this money going? Who is benefiting from it? The estimates are hardly objective. The second is that video is a more accessible format for the Brazilian population, and performance is associated with the way that you emotionally mobilize the audience.

The Other Side

When questioned about the rates of deforestation, the director of the feature-film Cortina de Fumaça (“Smokescreen”) and partner at Brazil Paralelo, Lucas Ferrugem, responded via email that it is not a far-right production. About the rates of deforestation, he said that the film shows “irrefutable data” and that “no country preserves as much as us, and whoever says anything to the contrary is lying.” Ferrugem says that the team sought to “escape narrative traps: you can fall into the temptation of wanting to respond to if global warming exists or not.”

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), responsible for synthesizing the global scientific knowledge on the subject, showed that if there is not a reduction in CO2 emissions around the world, global warming from 1.5ºC to 2ºC will be surpassed in the next decades. In Brazil, a member country of the IPCC, deforestation is one of the main sources responsible for the elevation of greenhouse gasses. Read Ferrugem’s response in its entirety here.

YouTube was also contacted for comment on the spread of denialist content about global warming and deforestation—in addition to the topics that make up the list of the 10 most-shared videos on Telegram—but it had not responded at the time of this report’s publication.

In another article for the project “Amazonas: Lies Have a Price,” the platform stated via the media relations officer, that all the content published on the platform must follow community guidelines that, among other practices, prohibit the dissemination of disinformation. According to YouTube, even if a video breaks the community guidelines but is not removed, it can lose monetization and have reduced viewing recommendations.

In October of this year, YouTube, which had already created guidelines for the dissemination of information about COVID-19, updated its monetization policies and ads about climate change and banned the remuneration of content that contradicts the scientific consensus about the existence and causes of climate change.

How to Deal with Disinformation Problems

Check out tips from those who work to combat lies shared on the internet, networks and apps.

Intervozes: This organization works for information and communication rights. In the book Desinformação: crise política e saídas democráticas para as fake news (Disinformation: Political Crisis and Democratic Departures to Fake News), introduces the environment of disinformation in Brazil and proposals to deal with this topic. Download the free book.

Pilares do Futuro: A digital platform that supports educators to create and develop educational activities focused on digital citizenship. In addition to various free materials, they also offer workshops. Check out their work here.

Redes Cordiais: This organization invests in media education to build healthier networks and high-quality information to guarantee a trustworthy environment. It offers courses, talks and more at: redescordiais.com.br

Veja também

Mentiras compartilhadas pelo Whatsapp enfraquecem luta indígena

Bombou no YouTube: o “novo índio” e a “nova Funai” de Jair Bolsonaro

A falácia da soberania nacional na Amazônia, segundo Izabella Teixeira