An exclusive survey shows that, between July and September, the period that marks the dry season, fires in lands with the presence of isolated peoples accounted for more than 25% of fires in indigenous areas. The most serious cases occurred on the border with the Cerrado, in Mato Grosso, Pará, and Rondônia.

A group of isolated indigenous people was sighted in June 2020 on the outskirts of the Uru-eu-wau-wau Indigenous Land, in central Rondônia. Two months later, Rieli Franciscato, coordinator of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Ethno-environmental Protection Front of the National Indian Foundation (Funai), was killed by an arrow fired by uncontacted natives. According to indigenous rights NGOs, these episodes may be reactions to irregular occupations in the territory.

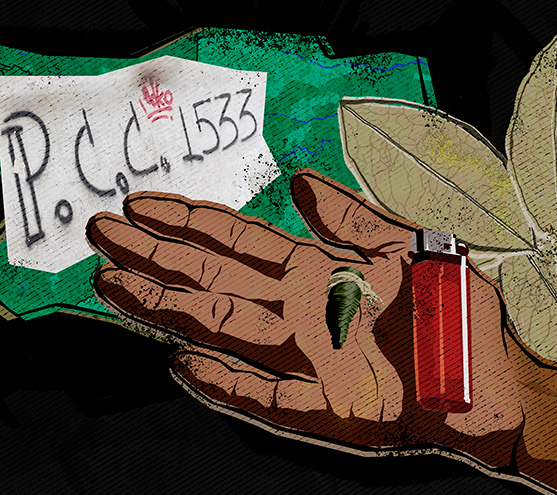

Fires, many of them illegal, pose some of the biggest threats here: between July and September, a dry period in the Amazon, around 25% of fires in indigenous lands occurred in those where isolated peoples` presence is either confirmed or under study. The information is from an exclusive survey carried out by InfoAmazonia for PlenaMata, based on records from the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe). Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau land is one of the most affected.

“The isolated people are being forced to leave because the indigenous land has been invaded by loggers, cattle raisers, miners, and other bandits, and have also been hit by fire. Something serious is happening in Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau”, warns Ivaneide Bandeira Cardozo, who has headed the Kanindé Ethno-environmental Defense Association in Rondônia since 1992.

The unprecedented survey reveals that there was at least one fire outbreak in all indigenous lands where the presence of isolated peoples is confirmed or under study by the National Indian Foundation (Funai). More than 13 thousand signs of fire (which are usually criminal fires) were registered between July and September in these territories, increasing threats to the survival of people and the forest itself. For the analysis, InfoAmazonia cross-referenced public data on the limits of indigenous lands, from Funai, with the records of forest fires from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) in the period, as well as with the fines applied by Ibama between July and August.

The results reveal a concentration of hot spots in areas between the Amazon and the Cerrado, in the Inãwébohona Indigenous Land, in Tocantins, and in the Xingu Indigenous National Park, in Mato Grosso, which concentrated more than half of the hot spots among indigenous lands with isolated indigenous peoples. Both territories are neighbors to large animal agriculture production sites.

In the general ranking, the indigenous lands most affected by forest fires are in Pará, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia. These states are are all leaders of deforestation in the tropical forest according to INPE. “Deforestation on indigenous lands is almost always followed by fire. This is more serious where there are isolated peoples. Indigenous peoples traditionally burn to prepare the land for clearing or to attract game, but they know how to control it, they don’t let the fire spread”, explained Fabrício Amorim, from the Observatory for the Human Rights of Isolated and Recently Contacted Indigenous Peoples (OPI).

Another indigenous land hit during the fire season, with 477 hot spots in three months (an average of 5 hot spots per day), is the one that shelters the isolated Piripkura people, in Mato Grosso. In the last 12 months, more than 3,500 hectares have been burned and 2,300 hectares have been deforested according to data from the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), which generates monthly bulletins with high-resolution satellite images on the situation of lands with isolated indigenous peoples.

Deforesting and then burning to form pastures is part of the modus operandi of those who oppose indigenous land demarcation. “They are burning everything down to form pastures, force a ‘fait accompli’ policy to reduce indigenous land. Something similar happened with the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve, in Rondônia. After they turned everything into pasture land, they argued that the area was no longer meeting its conservation objectives and that its limits were shrunken,” said researcher Antonio Oviedo, from ISA. Oviedo refers to the reduction of more than 90% of the protected area approved by state deputies in April. Only 22 thousand hectares of the original 193,000 hectares of the Jaci-Paraná reserve remain. The measure, sanctioned by Governor Colonel Marcos Rocha (no party), a Bolsonaro supporter, legalized land grabbing in the conservation unit, harming rubber tappers and traditional extractivists who worked there.

Among the ten indigenous lands with the presence of isolated peoples most affected by fire between July and September are also the Kayapó, Ituna-Itatá, and Munduruku lands in Pará, and Zoró and Aripuanã lands in Mato Grosso. Another land in the line of fire is the Vale do Javari Indigenous Land, in Amazonas, which is home to seven contacted peoples and also the largest isolated indigenous population in the world.

Ibama data analyzed by InfoAmazonia show more than R$471 million in fines applied for environmental crimes in indigenous lands with the confirmed or potential presence of isolated peoples between July and August.

Ituna-Itatá land leads in both the number of occurrences and the monetary value of sanctions, with 31 crimes recorded in the territory.

Ibama data analyzed by InfoAmazonia show more than R$471 million in fines applied for environmental crimes in indigenous lands with the confirmed or potential presence of isolated peoples between July and August. Ituna-Itatá land leads in both the number of occurrences and the monetary value of sanctions, with 31 crimes recorded in the territory. The value of one of the fines reached R$ 50 million for the deforestation of 10,000 hectares.

It was received by businessman Jassonio Costa Leite. He earned the nickname “King of Land Grabbing” after federal investigations identified him as the head of a scheme to squash indigenous lands and destroy over 21,000 hectares of forests in Pará. The case was brought to attention in April by Estadão, which also showed Leite’s connections with politics in Brasília (DF).In July, the businessman was the target of an action by the Federal Police to investigate crimes in the Ituna-Itatá Indigenous Land. InfoAmazonia tried to get in touch with the businessman, but he did not respond.

Experts credit part of the spread of forest fires to poor enforcement. A balance sheet by the Institute for Socioeconomic Studies (Inesc) reveals that this year only 22% of the budget available for Ibama and ICMBio to combat deforestation and forest fires was used. Of the R$384.9 million allocated in 2021, R$83.5 million was used and another R$187.5 million was set aside for future payments.

Sought by InfoAmazonia, Ibama did not respond to our requests for an interview. Funai, on the other hand, said it did not have “a spokesperson available at the moment” and sent a note stating that it “carries out continuous surveillance and territorial inspection actions” in indigenous lands in the Legal Amazon. They also say they’ve inaugurated and reactivated nine Ethnoenvironmental Protection Bases in the region and that “from 2019 to 2020 there was a 23.3% reduction in the area subjected to deforestation in Indigenous Lands in the Legal Amazon”.

The reduction in deforestation that Funai is referring to is similar to that boasted by Jair Bolsonaro at the 76th General Assembly of the United Nations, in New York, in September. Oviedo says the data presented by the president to governments around the world distorts reality. “Deforestation alerts reduced by 32% between August this year compared to the same month in 2020, shows INPE. The government selectively publicize this piece of data trying to show that deforestation was falling. But that’s not the whole picture”, he said. “The reality is that the destruction of the Amazon has been breaking monthly records since 2019. In indigenous lands, the complete felling of the forest is the last stage of degradation preceded by invasions, theft of wood, cattle raising, mining, and arson”, completed the researcher.

In addition to being sources of CO2, deforestation and fires have worsened the covid-19 pandemic in these areas. A study, published last October by the Center for Economic Policy Research showed that every square kilometer deforested generated a 9.5% increase in new infections within two weeks of the episode. Indigenous people are the most affected by this trend due to contact with infected loggers and miners. Criminal deforestation accounted for at least 22% of covid-19 cases among these peoples by August 2020. Indigenous people are the most vulnerable population to the virus, according to the world’s largest survey on COVID, carried out by the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel) with funds from the federal government. The results caused discomfort at the Presidental Palace, which censored data and discontinued the study. Jair Bolsonaro claimed that he did not have a budget to improve assistance to the indigenous population and vetoed parts of an approved law that ensured drinking water, food baskets, and beds in hospitals for indigenous people during the pandemic. The measures were overturned by Congress. According to the Indigenous People’s Movement of Brazil (Apib), 1,618 members of 162 different indigenous peoples died due to covid-19 up to the publication of this story.

Brazil is the only country with a real non-contact policy

The Brazilian government has already recognized 28 isolated peoples in the country. Another 86 are awaiting confirmation. One case is in the Cerrado and all the others are in the Amazon. Populations like these are increasingly rare around the world. There are groups in Papua New Guinea, in Oceania. But Brazil is the only one that maintains a strict non-contact policy between isolated groups and non-indigenous people. “The right of these populations to live in isolation is guaranteed in the Constitution and federal legislation,” said Beatriz Matos, from the Brazilian Association of Anthropology (ABA) and a professor at the Federal University of Pará. “Formally we have a legal framework that should rid these peoples’ territories of hunters, loggers, miners, and missionaries who want to convert them to other religions. But this is not fulfilled, especially in this government. There is a strong deterioration in environmental inspection, laws, and regulations,” he warned.

We have a legal framework that should rid the territories of these peoples of hunters, loggers, miners, and missionaries who want to convert them to other religions. But this is not fulfilled, especially in this government. There is a strong deterioration in environmental inspection, laws, and regulations.

Beatriz Matos, professor at UFPA

The consolidation of an indigenous land is processed by Funai, the Ministry of Justice, and the Presidency of the Republic. During this process, the area must be delimited and demarcated, non-indigenous people must be removed, and the land must be identified with signs and finally ratified as a property of the Union where certain populations can live freely. Territories have temporary restrictions on access by non-indigenous people in the face of traces of the presence of isolated peoples. If confirmed, there are measures in place to reinforce its demarcation.

However, FUNAI ordinances that restrict the expansion of agriculture and the exploitation of resources by non-indigenous peoples will no longer be valid by March 2022 in the Piripkura, in Mato Grosso; the Pirititi, in Roraima; the Jacareúba-Katawixi, in Amazonas; and the Ituna-Itatá, in Pará, the most deforested indigenous land in the country in 2019. NGOs estimate that isolated peoples in these areas will be decimated by loggers, land grabbers, and miners if the measures are not quickly renewed by the agency. The Federal Prosecutor’s Office asked for an urgent extension of the ordinances. An online NGO petition puts pressure on the agency.

In September, Funai updated the restriction on the use of Piripkura Indigenous Land, but for only six months. Sources interviewed by InfoAmazonia assess that precarious measures such as this could lead to the non-recognition of the presence of isolated peoples due to the occupation and degradation of these lands. “This encourages more invasions, deforestation, and aggression against indigenous people. All so as not to upset the retrograde agroindustrial lobby that supports this government,” said Fabrício Amorim, from the OPI.

“This renewal is made for invaders to finish their job.” In six months they will not complete the demarcation or remove invaders from the indigenous land, which can then be reduced by Funai”, said Matos. “Funai will play dumb so as not to demarcate. This is a portrait of the negligence of the agency and the government with the alarming situation of isolated peoples”, reinforced Samara Pataxó, one of the coordinators of Apib’s legal department. Funai did not respond to our request for an interview.

Other areas under restricted use are the Kawahiva indigenous lands of Rio Pardo, between the states of Amazonas and Mato Grosso; Igarapé Taboca do Alto Tarauacá, in Acre, and Tanarú, in Rondônia. The latter is home to the “Indio do Buraco”, the last survivor of an indigenous people that were decimated in that state. These Funai ordinances do not expire in the short term, informed the ISA.

Frauds in forestry legislation also intensify disputes over indigenous territories. The four lands with use restrictions expiring in 2022 are crisscrossed with Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) : Mandatory self-declared electronic registration aimed at environmental regularization of rural real estate throughout the country.(+) Almost 54% of the Piripkura land area is covered by CAR applications, or 131,000 of its 243,000 hectares. In Ituna-Itatá, Pará, this index reaches 90%, or almost 130 thousand hectares out of 142 thousand hectares.

According to Imazon researcher Brenda Brito, the Pará Environment Secretariat (Semas) does not inform how many records are being analyzed in the 43 indigenous lands in the state. In addition, she considers that CARs are not being canceled by the state in lands such as Ituna-Itatá. “Semas indicates only two registrations canceled in this same Indigenous Land”, he described in his column for PlenaMata.

Deputy Secretary at the Pará Environment Secretariat Rodolpho Bastos stated that around 40,000 of the more than 256,000 state records have already been analyzed. Monthly evaluations would reach 3,000 cases. He also said that the most deforested and fully regularized indigenous lands are prioritized in assessments, such as Cachoeira Seca and Apyterewa.

“Depending on the level of overlap with Indigenous Land, from 5% to 50% or even more, registrations are suspended or immediately canceled. Today about 700 CARs are canceled in Indigenous Lands throughout the state. But registrations are self-declaratory and a registration canceled today may come back tomorrow. It’s like drying ice. Applications claiming lands in protected areas should be barred by legislation”, he emphasized.

Registers suspended by the government of Pará block the trade of goods produced in properties overlapping with indigenous lands due to agreements signed by companies in the meat and grain sectors with the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPF). But an ordinance published in May by the Ministry of Agriculture clashes with the state rule and rates any registration in protected areas as “pending”. “This opens a loophole for the sale of items produced in areas overlapping with indigenous lands”, complained Bastos.

“Companies that have not signed agreements with the MPF are the majority in the Amazon and may be buying meat and other items produced in areas whose CARs overlap with indigenous lands and other protected areas”, said Mauro Armelin, executive director of the NGO Amigos da Terra – Brazilian Amazon.

The Ituna-Itatá Indigenous Land was defined in 2011 as a condition for the construction of the Belo Monte mega hydroelectric plant. Its occupation by non-indigenous people began to grow in 2014, under the administration of Dilma Rousseff (PT). Since 2016, when Belo Monte started operating, under the Michel Temer (MDB) government, CAR registries and deforestation have advanced in that territory. “These registrations should be canceled immediately. In the Pirititi and Jacareúba-Katawixi lands, there are nearly 1,200 CAR records and thousands of hectares with mining requirements. Ituna-Itatá even has villages with non-indigenous people. The invaders will be rewarded if these territories are not consolidated as indigenous lands that will also protect isolated peoples”, highlighted Antonio Oviedo, from ISA.

The Threat of the Time Frame Thesis

Bills being processed in the National Congress and the judgment of the so-called Time Frame Thesis in the Federal Supreme Court (STF) also threaten the future of indigenous populations and lands. Bill 490 ends demarcations and allows the review of all Indigenous Lands in the country, as well as opening up territories for agriculture, mining, and other economic activities. The text received the green light in June from the Chamber of Deputies’ Constitution and Justice Committee and, if approved on the floor, will go to the Senate.

The proposal, by former rural lobby congressman Homero Pereira (1955-2013), is anchored in the time frame thesis, used by parties interested in indigenous territories since 2009, when then-STF minister Ayres Britto proposed its adoption in the judgment that validated the demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land, in Roraima. According to the thesis, indigenous peoples only have the right to lands they already occupied in the enactment of the Federal Constitution, in October 1988. The Court linked the judgment to the case of an indigenous land in Santa Catarina, inhabited by the Xokleng, Kaingang, and Guarani peoples.In September, the judgment of the time frame thesis was followed by thousands of indigenous people camped in Brasília, in one of the biggest organized movements ever carried out by the native peoples of the country. During the same period, Bolsonaro supporters came to the federal capital to defend the government and criticize the Judiciary and Legislative powers. Jair Bolsonaro said at the time that a denial of the time frame thesis by the STF would harm the economy and agribusiness. Earlier, in August, he labeled the Court’s decisions a “white dictatorship”.

Maintaining indigenous lands helps balance the climate, maintain biodiversity and the rains that fall in the countryside and cities. Brazil will not comply with international agreements in these areas without respecting indigenous rights. This benefits present and future generations and the future of the planet.

Carolina Santana, from the Observatory for the Human Rights of Isolated and Recent Contact Indigenous Peoples (OPI)

According to Carolina Santana, legal advisor for the Observatory for the Human Rights of Isolated and Recently Contacted Indigenous Peoples (OPI), the time frame thesis is absurd and cannot be applied, especially to populations that do not act directly for their rights and whose location was unknown in 1988. That year, there was no evidence of an isolated population in the Kawahiva Indigenous Land of Rio Pardo, whose presence was confirmed in 1999. Until today its demarcation has not been finalized. The vast majority of isolated peoples in Brazil were recognized by Funai after 1987.

“People without contact do not manifest themselves through the formal means of governments. If the time frame thesis is validated by the STF or approved by Congress, all studies and demarcations will be halted, and indigenous lands may be dismantled. The constitutional rights of known and uncontacted populations will be denied. The message will stimulate more trampling of rights and violence against these people”, he warned.

Also during the 2018 electoral campaign, candidate Jair Bolsonaro stated: if “I take over as president of the Republic, there will not be a single further centimeter for demarcation” of indigenous lands. “The Indian is our brother, he wants to be reintegrated into society. Indians already have too much land, let’s treat them like human beings, there are Indian lieutenants in the Army, the president of Bolivia [Evo Morales], they don’t want to live in a zoo”, added the then federal congressman for the PSC from Rio de Janeiro. A survey by the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) shows that demarcations of indigenous lands have fallen since Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s first term (1995-1998) and were reduced to zero in the current government.

“Demarcation seeks to keep non-indigenous people out of these lands, where indigenous peoples live without destroying the territories. Demarcation is the best possible measure given our generally violent and genocidal relationship against these peoples. If we had a better relationship with the land and its populations, we might not need indigenous lands”, pondered Beatriz Matos.

Recognizing the rights of indigenous populations can also help the country in other agendas, analyzes Carolina Santana, from OPI. “Maintaining indigenous lands helps balance the climate, maintain biodiversity, and the rains that fall in the countryside and cities. Brazil will not comply with international agreements in these areas without respecting indigenous rights. This benefits present and future generations and the future of the planet,” she highlighted.

This is an story by InfoAmazonia for the PlenaMata project.

Juan Ortiz collaborated with data analysis.