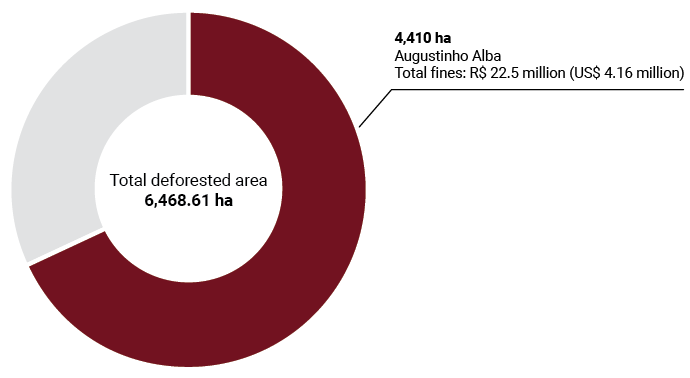

In the municipality of Altamira, Pará, almost 6,500 hectares of public forests were cut down in 2020. One of the people responsible deforested 60% of this area and did not stop even after being fined by Ibama.

A forest of 6,500 hectares disappeared in 18 months in the Amazon. And it wasn’t for lack of warnings. Between February 2, 2020, and August 18 of this year, satellite monitoring systems, especially DETER, run by National Institute for Space Research (INPE), issued 89 alerts to environmental agencies informing them that clearings were opening in the green south of Altamira, in Pará, in protected areas through which the Curuá river runs.

The total deforested area was confirmed in October 2020 by MapBiomas with high-resolution satellite images. The deforestation took place in an area belonging to the Union, on public lands that have not yet been officially designated – whether for conservation, traditional or indigenous populations, agricultural production, or other economic uses.

InfoAmazonia carried out a survey to identify the exact location of the most deforested area and whether those responsible were penalized by IBAMA or the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPF). To do so, we crossed the polygonal area identified by MapBiomas with data from Ibama’s infraction notices, MPF documents, protected areas, and areas of non-designated public lands. We found that the deforestation took place on Union properties close to two indigenous lands and one full-protection conservation unit. The survey indicated that there was a million-dollar fine on the eastern edge of the polygon, near the Curuá river. We contacted IBAMA, which confirmed that two people were being held responsible for taking down the forest in the area. One of them, who deforested 4,410 hectares, is Augustinho Alba, named by Veja as one of the largest culprits for deforestation in the Amazon between August 2019 and July 2020.

In July of last year, Alba was fined US$ 4,16 million (R$ 22 milhões) for deforestation without authorization. He is being sued by IBAMA. This year, he received another US$ 96,622 (R$ 510 mil) fine for disrespecting the environmental agency’s embargo. According to a 2016 IBAMA ordinance, the measure serves to “stop ongoing environmental infringements, prevent new infringements, safeguard environmental recovery and guarantee the practical result of the administrative process”. In Alba’s case, it didn’t work – he continued destroying or illegally occupying the area despite this impediment.

We tried to contact Augustinho Alba by phone, but a recording informed us that the number was not available for calls. We also sent e-mails to lawyers acting in the lawsuit filed by Ibama. There was no response up to the date of publication(the text will be updated if they respond). To Veja, Alba said that the infraction is “false information” passed on by a “bunch of PT (Workers’ Party) members”. The fine, however, was issued on July 10, 2020, when Ricardo Salles, responsible for paralyzing the institution, was still in charge of the Ministry of the Environment (MMA).

Ibama, an autarchy linked to the MMA, also reported that one of Alba’s “neighbors” “was fined R$22,521,600 (US$ 4,16 million) for destroying 3,002.88 hectares of forest, in addition to being embargoed”. The crime would have occurred in the same area where MapBiomas identified the highest number of deforestation alerts between February 2020 and August of this year. Through Ibama’s database, it was not possible to confirm the offender’s name.

Free pass to deforestation

The case of the largest deforested area in Brazil in the last 18 months reveals an upward trend in criminal deforestation of non-designated public forests. Data from the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (Ipam) shows that between August 2019 and July 2020, 226.5 thousand hectares of undesignated forest areas were deforested. This represents 20% of all destruction recorded in the Amazon in the period.

This occurs above all with the formation of pastures for the illegal occupation of federal ‘vacant’ lands. Then they try to legalize the crime and get credit from banks by enrolling in the Rural Environmental Registry, the CAR. They also act against land title regularization and the creation of protected areas.

Antônio Fonseca, reseacher at Imazon

In the case of the area deforested by Augustinho Alba, access for tractors and machines used to cut trees was facilitated by the proximity to the BR-163 federal highway, a significant axis of environmental destruction. The polygon is just 12 kilometers from the highway, in a section between Cuiabá (State of Mato Grosso) and Santarém (State of Pará), approximately 1780km from each other, the paving of which was finished this year.

A large part of the road was granted by the government to the private sector for ten years. It is used mainly by trucks taking soy and other commodities from producing areas to ports for exportation. A report by InfoAmazonia showed that deforestation exploded 359% along the highway from the border with Mato Grosso in the south to the town of Castelo dos Sonhos in Altamira’s northern edge in the first four months of this year alone, compared to the same period in 2020.

The highway enabled access to previously preserved areas. According to Imazon researcher Antônio Fonseca, deforestation is spreading from the Arc of Deforestation to previously untouched areas of the Amazon, breaking monthly, rather than annual, records. “This occurs above all with the formation of pastures for the illegal occupation of federal ‘vacant’ lands. Then they try to legalize the crime and get credit from banks by enrolling in the Rural Environmental Registry, the CAR. They also act against land title regularization and the creation of protected areas”, he said.

Parallel to the BR-163 route, the Ferrogrão project could further expand the already intense land grabbing and deforestation in Pará and Mato Grosso. A study by the Federal University of Minas Gerais estimates that the 1,000 km of railroad between Sinop (MT) and Itaituba (PA) will affect 4.9 million hectares of protected areas in municipalities that already accumulate 1.3 million hectares of illegal deforestation.

Also of interest is the region of Altamira, since it is surrounded by protected areas rich in wood and other natural resources, such as the Serra do Cachimbo Biological Reserve and the Menkragnoti and Baú indigenous lands. The Kayapó live in these lands, along with isolated groups with little or no contact with other indigenous peoples or with the urban population. A swathe of deforestation laying bare 6,500 hectares almost reaches the banks of the Curuá River.

Pará, the state with the most deforestation in the legal Amazon, also concentrates the largest number of Federal Public Ministry (MPF) actions against deforestation – the lawsuits are carried out in secrecy, and it is not possible to obtain the names of those accused. From January 2019 to June last year, there were 704 lawsuits pertaining to illegal deforestation in the state. It is the highest rate among the Amazonian states in the period. Of the total actions, 127 were in Altamira, where Augustinho Alba was caught for deforestation, and 65 in neighboring Novo Progresso. In March of this year, as a result of previously filed lawsuits, three farmers were sentenced to pay a sum of US$ 1,68 million (R$6.8 million) in compensation for deforesting 1,680 hectares in these municipalities – Augustinho Alba is responsible for the deforestation of an area 2.5 times as large.

Criminals simulate the occupation of deforested public areas with cattle to circumvent an eventual inspection, which will never find anyone to be held accountable on the spot. Faced with new instances of deforestation, the area is forgotten by authorities in a few years. Then it is used or sold. Laws are repeatedly passed legalizing land grabbed lands and other crimes.

Daniel Azeredo, Federal Prosecutor

Part of this deforestation may have originated in logging. A report by Rede Simex, formed by the NGOs Imazon, Idesam, Imaflora, and IC, shows that 55% of tree removals in Pará between August 2019 and July 2020 did not have authorization from environmental agencies. The area (50.1 thousand hectares) corresponds to almost half the size of the city of Belém.

According to Simex, in the Indigenous Land of Baú, close to the deforested polygon, 158 hectares were affected by logging. The invasion of indigenous lands by loggers and miners has changed the local landscape. According to indigenous leaders, the crystal-clear waters of the Curuá, which rises in the Serra do Cachimbo mountains and crosses the Menkragnoti and Baú lands, have become like “coffee with milk”. “The asphalt facilitated access to the region. Soybeans and deforestation have already touched our territories. The government does not comply with environmental law or with ILO Convention 169”, complained Doto Takak-Ire, from the Kabu Institute.

Sought out by the report, the Pará Environment Secretary’s Office did not report on what measures it has taken to curb deforestation in the region and speed up land tenure regularization on land under its administration.

Surplus monitoring, lack of inspections

Ane Alencar, the Director of Science at Ipam, points out that today there is enough information for preventive and strategic actions in the most problematic regions regarding environmental offenses in Pará. “The deforestation alerts are a great tool for public agencies to act against these crimes”, highlighted the doctor in Forest Resources and Conservation from the University of Florida.

The Federal Public Ministry (MPF) also uses data from environmental agencies and satellite images to prosecute criminals. Between 2017 and 2019, the agency identified 321,000 hectares of illegally deforested land, including lands in so-called “protected areas” in the Amazon.

“We use the tools available to us to identify and fight more offenders simultaneously and at a lower cost compared to field inspections. Through our actions, we try to reduce land grabbing by asking that the areas targeted by crimes are not designated until damages have been compensated”, explained Federal Prosecutor Daniel Azeredo.

Azeredo assesses that the growing deforestation in Altamira was predictable and is due to its favorable position for agribusiness: supervision by public authorities is weak, it’s located near exporting ports, and infrastructure projects have deeply impacted the region. “Criminals simulate the occupation of deforested public areas with cattle to circumvent an eventual inspection, which will never find anyone to be held accountable on the spot. Faced with new instances of deforestation, the area is forgotten by authorities in a few years. Then it is used or sold. Laws are repeatedly passed legalizing land grabbed lands and other crimes”, explained the prosecutor, referring to the chronic cycle of deforestation in the Amazon.

In early August, the lower house of Congress approved Bill 2633, called The Landgrabber’s Bill by environmentalists. Specialists such as researcher Brenda Brito from Imazon assess that this is yet another law that will give amnesty to land grabbers and pave the way for the privatization of public lands. The proposal still needs to be considered by the Senate.

Annual deforestation has increased by 450% in Altamira over the past nine years. According to Imazon, it has grown from 114 km2 (2012) to 625 km2 (2021) per year, totaling 3,083 km2. The first seven months of this year have already accumulated forest losses of 432 km2 in the municipality alone.

Areas dedicated to pasture grew alongside the loss of forests. Altamira’s pasture areas have increased almost 850% since 1985, leaping from 83.5 thousand hectares to 783.5 thousand hectares, according to MapBiomas. Almost 1,800 km2 of forests fell between 2010 and 2014 around the Belo Monte mega-plant. Losses are 40% higher than estimations without the hydroelectric plant.

Brazil is prepared to reach zero deforestation

In Brenda Brito’s assessment, accelerating land title regularization for rural production or nature conservation is one of the urgent measures to curb deforestation and attract more qualified investments in the Amazon. In Pará alone, there are around 35,000 land regularization processes linked to the Instituto de Terras do Pará, distributed among different state agencies. An Imazon study estimates that at the current pace of assessment and digitization, it would take 79 years to go through all the paperwork. In the state and the rest of the Amazon, there are also numerous federal lawsuits over land titles. Land chaos fuels deforestation.

According to Brito, continuing to entitle lands with illegal deforestation and making federal and state laws more flexible will only fuel new crimes. “Deforestation can be allowed on legalized lands, but there would be control over the responsible parties. If not, they will deforest everything before receiving a deed. At the same time, it is necessary to move forward with the creation of protected areas and to make quality investments to modernize the state’s land data and licensing systems”, she pointed out.

For economist André Cutrim Carvalho, a professor at UFPA, public economic policies to expand and intensify agricultural production in areas that have already been affected would also put a brake on deforestation. “The general idea is that the market should prevail, but we are seeing the disastrous effects of fires used to create pastures and extensive cattle husbandry. Following this, we will have increased costs for conservation and restoration of what was destroyed, and the region will lose attractiveness for investments. This bubble will burst”, he said.

From attorney Daniel Azeredo’s point of view, it is essential to track all production chains in the Amazon. After all, “without a broad and reliable traceability, illicit products will continue to be traded together with legalized goods”.

Brazil already has the technical and political capacity to adopt this control and stop the destruction of the forest, says Fonseca, from Imazon. Active between 2002 and 2020, the Action Plan for Control and Prevention of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon reduced deforestation to its lowest historical rate in 2012.

“We had a combination of actions and stakeholders that contained deforestation. Brazil knows how to do this. Our global example needs to be resumed, not least because the largest world economies are turning to green agendas. But these positive changes have to reflect in economic gains for local society”, he highlighted.

According to Ane Alencar, director of Ipam, controlling deforestation and making cattle husbandry more efficient would maintain forests and their benefits, such as reducing Brazil’s contribution to global warming. Today, we are the sixth-largest contributor to the climate crisis. “For Brazil, it is cheaper to cut emissions currently fueled by deforestation, as we still don’t need to focus heavily on energy generation or transportation. We must take advantage of this and position ourselves differently in the global climate debate. Maintaining our natural heritage will reduce emissions and will be a win-win situation for the country”, he highlighted.

Reporting by InfoAmazonia for the PlenaMata project.

Collaborations from Juan Ortiz (geospatial data analysis) and Carolina Passos (data visualization).