Diana Ríos Rengifo took on the defense of the Peruvian Amazon after the murder of her father, a well-known Asheninka leader in the fight against illegal loggers. The trees in Saweto, a community located near the Peruvian border with Brazil, are highly coveted on the market and are threatened by indiscriminate logging.

By Aramís Castro

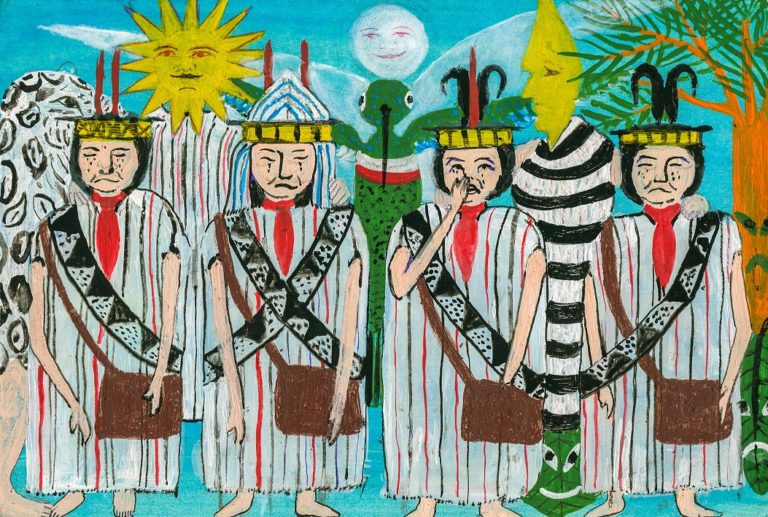

In addition to forests, winding rivers and species that science has yet to discover, the Peruvian Amazon is also home to the meiri, squirrel whose tail seems to replicate in the hairstyle of Asheninka indigenous girls. For Jorge Ríos Pérez – a leader who was killed along with three others by illegal loggers on September 1, 2014 – the resemblance was undeniable: every time he saw his eldest daughter he thought of that elusive little animal, which is why he began to call her Meiri when she was a child.

Accepting the death of a parent is painful, and to do so without a body to mourn is even worse. Six years after the murder of Rios Perez, the authorities have yet to search for his remains. And, today, although he does not physically accompany her, Diana Ríos Rengifo feels her father is still out there, in nature, the place where he taught her to stand up and fight.

“He is in the forest. The forest is life and, thanks to it, I am alive,” she says.

Ríos Rengifo is a reserved woman who divides her time between raising her children and defending the land. “Sometimes, I wish there were more than 40 Dianas who struggle, who propose things, and who get it all done,” she says, emphasizing her last words.

Six years after her father was murdered, she is determined to support any indigenous community that begins the process of securing deeds to its land or seeks to expand the areas recognized by the Peruvian state. It is a struggle Ríos Pérez entrusted to her shortly before his death.

On Sunday, August 31, 2014 – the last time Diana saw her father – he was on his way to the indigenous community of Apiwxta, near the Brazilian border, to meet with other leaders who had allied themselves with Saweto’s fight against illegal timber trafficking. Before starting that trip, he made a brief stop at his daughter’s house to pick up a pair of propellers he needed for his little boy, a small boat named as such because of its noisy engine.

At that meeting, Diana gave him a bottle of masato – a fermented yucca-based drink that is traditional in the Amazon region – being certain she would see him again on Friday of the following week, at the very latest. That morning, she remembers he looked anxious about the meeting. And, shortly before saying goodbye, he said something that would stay with her throughout the day: “If anything happens to me along the way, you’ll be in charge of taking care of your mom and your little brothers and sisters, and continuing the fight,” he said.

Ríos Pérez’s death not only widowed Diana’s mother, Ergilia Rengifo López, but also left nine siblings without the head of their household. One of them was barely a month old. So, Diana – the eldest – had to take on a new role: that of becoming a leader to find justice for the murders and to persist in the defense of antamiki (the Amazon forest).

Asheninka Resistance

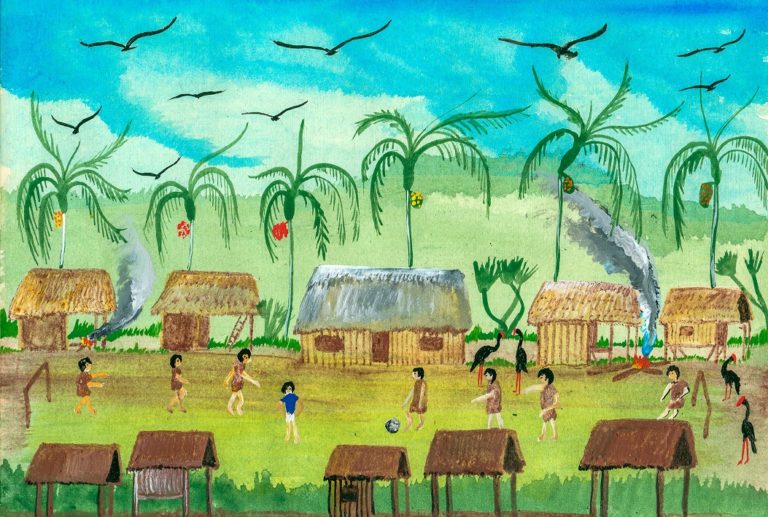

Saweto is a Peruvian indigenous community located near the Brazilian border. To get there, one must travel by boat for a week from Pucallpa, the capital of the Ucayali region. Within its territory, which extends across 77,000 hectares of deeded land recognized by the State, there are trees whose wood commands a high price on the market: cedar, mahogany and shihuahuaco, the latter being threatened by indiscriminate logging.

The presence of illegal loggers is not unusual in region’s forests, and Diana’s father and the three community leaders who were killed with him – Edwin Chota Valera, Leoncio Quintísima and Francisco Pinedo – had been threatened previously on a number of occasions.

Since his death, Diana has been forced to deal with successive delays in the search for those responsible and with evasiveness on the part of the authorities who are in charge of the investigation. This had happened already in the past, with the complaints filed by Edwin Chota Valera, a former Asheninka chief in the community. Six years earlier, Chota had begun a legal battle to demand an investigation into the presence of illegal loggers in the forests of Saweto. And, although the authorities knew the community was being harassed by loggers, the inquiries by the Ucayali Environmental Prosecutor’s Office did not begin until the crime became known.

The investigation by the Environmental Prosecutor’s Office was analyzed in Saweto: The Violence of Impunity in the Amazon, a report by OjoPúblico, which revealed a chain of irregularities and efforts to dismiss the information presented by local leaders to support the complaint; namely, photographs of those involved in unlawful logging and the coordinates of where they were operating illegally. Moreover, for four years, that office ignored the testimony of a witness regarding the identity of the person who masterminded the crime and the identities of those who carried it out.

Along with these problems, the task of representing the case before the media and international organizations fell to Diana. She was only 22 years old. That responsibility led her to travel outside Saweto for the first time, in November 2014. She left her community of 30 families and traveled more than 3,000 miles to New York City, a cosmopolitan American metropolis of more than 8.6 million people. The reason for the trip was to receive an award presented by the Alexander Soros Foundation to commemorate the Asheninka who have fallen in the fight against illegal logging.

Those were days of sudden changes for Diana. From a routine in a small community without basic services, she moved on to interact with news agencies and civil-society organizations in a city with inhabitants of different nationalities and cultures.

Robert Guimaraes, then leader of the Federation of the Native Communities of Ucayali and its Tributaries (Feconau) and the only Peruvian who accompanied her on that journey, recalls the culture shock: “She was surprised to be in a city this big and with such high buildings. She was attracted to modern things. But she was always sad because the events [murders] were recent.”

Guimaraes also remembers a moment during the ceremony when he believes Rengifo became convinced that she should continue to defend the Amazon region. “She broke down when they showed us a video on Saweto’s struggle. When pictures of Edwin Chota and his community were passed around, her eyes filled with tears. But I think she knew her struggle had to continue, and that gave her strength,” he says.

The burden of being a leader

Representing a community threatened by illegal logging is not easy, and even less so when it comes to a sudden legacy. For Margoth Quispe, a friend of Diana’s and a lawyer who is accompanying the Saweto case, Rios’ successor needed a break from mourning, but the opposite happened: Diana, along with the widows of those where killed, began to suffer a degree of exposure in the press that overwhelmed them. Quispe says Diana did not show her discomfort in a categorical way, but you could see it in her short statements to reporters.

“She was not prepared for it. She needed to understand what had happened and what was going to happen to her and her family. She didn’t have time to pause and say, ‘I’m going to do this or that from now on.’ The pressure was intense,” says Quispe, who also witnessed Diana’s initiation to the cause at meetings to define strategies for securing deeds to the community’s land, something that was achieved almost a year after the multiple murders were committed.

Progress like that helped Diana to persist in her defense of the Amazon region. After a decade of active participation in Saweto, she has become a reference in the environmental and indigenous struggle. That commitment, however, has not sidelined her search for justice or the need to one day find her father’s remains.

In the indictment against Eurico Mapes, José Carlos Estrada, Hugo Soria and the brothers Segundo and Josimar Atachi Félix, the alleged killers of the Asheninka leaders, it was suggested that the skeletal remains of the unidentified victims be found and identified; specifically, those of Diana’s father and Francisco Pinedo Ramírez. The process, however, is being held up due to lack of a response from the Ucayali branch of the judiciary.

This uncertainty led Diana to believe for a long time that her father had not died. “I found his sweater, his backpack, but not him. So, for me, it was as if he were alive,” she says in a broken voice.

However, in 2018, she performed a ritual with ayahuasca – a traditional Amazonian drink with hallucinogenic effects – as part of her mourning process. “I wanted to do a session, to see inside myself [and to check] if my father was alive or dead. For me, he was alive at every moment. But, when I took [ayahuasca], I saw what they did to him that day. Yes, it was him,” she says.

New coexistence

Today, if Diana represents Saweto’s face to the world, her mother does the same within the community. Ergilia Rengifo López works on the town council, through which she organizes and coordinates social programs. At the beginning of 2020, Diana and her mother decided to move to the outskirts of Pucallpa to accompany the judicial process from the capital of Ucayali, but they are still in contact with local leaders to stay informed about what is happening in Saweto on a daily basis.

In this new coexistence with her large family – made up of her mother, siblings and children – Diana has not lost the opportunity to teach the youngest members of her household the significance of their culture. In Asheninka, she explains to them the importance of defending the Amazon, perhaps in the hope they will follow in her footsteps and help to realize her wish for “40 Dianas”.

“I [want] them to understand a little tree is like a child, that you plant it and take care of it. If we don’t and we wrongly exploit that tree, it will die; and, it is as if a child were dying,” she says, imitating the teacher who was her father.

In the midst of the pandemic that paralyzed the entire apparatus of the government, Diana awaits the resumption of the judicial process far from Saweto, but with the hope of returning. There is no exact date for her return, nor for the start of the judicial hearing in Ucayali against those accused of the murders. On August 21, it was postponed for the fifth time.

Meanwhile, as part of her most urgent activities, Diana took quick tests and medicine to the indigenous communities bordering Saweto – San Miguel de Chambira, Putaya and Tomajau – that are combatting Covid-19. In Ucayali, the region where these and other indigenous communities are located, there are already more than 15,000 positive cases.

While flying over the area in a small plane, the Asheninka leader felt mixed emotions. Seeing the forest again brought back memories of her childhood. But, at the same time, she thought about the murder of her father.

“I was born in that forest and grew up around it. It’s up to everyone to understand, but for me it means a lot,” she said one night in August, while monitoring on her cell phone the latest emergencies of the day in Saweto.

(Translation: Sharon Lee Navarro)

This article is part of #DefendWithoutFear, a journalist series that tells the stories of women and men who struggle to defend the environment in a time of pandemic. Developed by Agenda Propia, in coordination with twenty journalists, editors and allied media in Latin America, the series is made possible thanks to support from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a global NGO.