A new deforestation alert system lets users know about forest changes in just a week.

Currently, GLAD alerts are available for Peru, the Republic of Congo, and Indonesian Borneo (though coverage will be expanding), giving administrators in those countries the opportunity to respond quickly to illegal logging and other illicit forest activities.

“It’s going to be very, very helpful,” Brian Zutta Salazar, a scientist specializing in remote sensing at the Peruvian Ministry of the Environment in Lima, told Nature.

Peru has seen particularly high increases in deforestation over the past few years. Gold mining is stripping forest along rivers and into protected areas in the Madre de Dios Department of southern Peru. In the north, a large cacao plantation touted as sustainable by industry reps has displaced old-growth rainforest. Palm oil plantations are becoming established in the country’s midsection. In total, GFW and government datasets both show Peru lost around 180,000 hectares of tree cover in 2014, up about 70 percent from 2000 levels.

The new GLAD data shows this activity slowed somewhat in 2015, with researchers from the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) estimating a total loss of 158,650 hectares of Peruvian tree cover last year based on nearly 1.5 million GLAD alerts. However, early 2016 numbers show a huge uptick from 2015. In January and February of last year, the GLAD system shows there were 13,071 tree cover loss alerts in Peru; in the same time period this year, there were 91,389 alerts.

In other words, GLAD alerts show there was a more than seven-fold increase in areas affected by tree cover loss in Peru from 2015 to 2016.

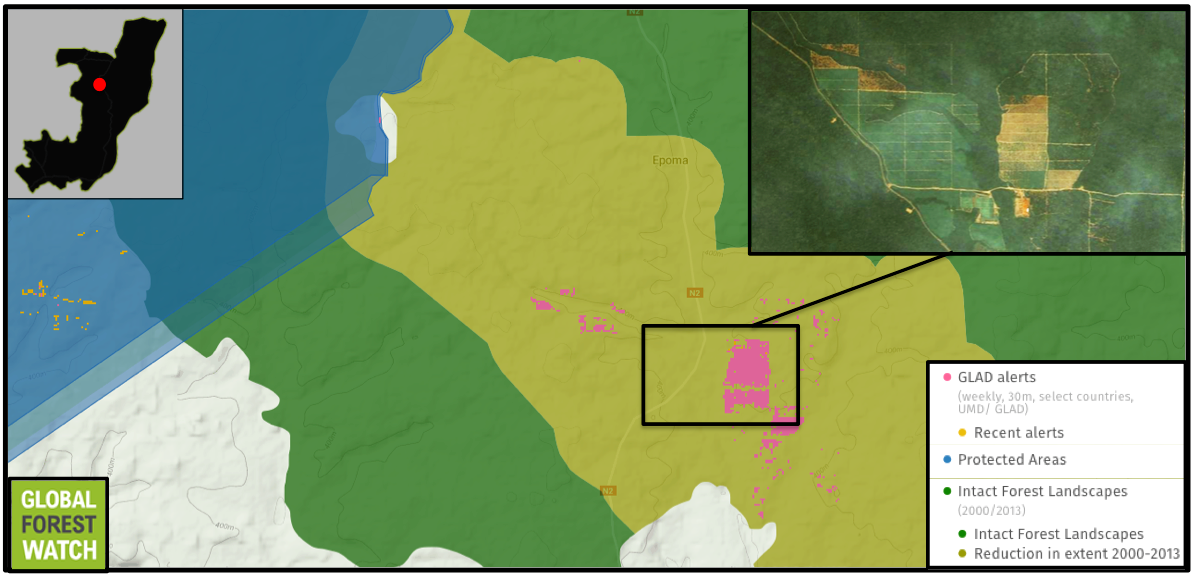

The Republic of Congo (RoC) still contains vast tracts of uninterrupted Congo Basin rainforest, home to endangered species like western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla), red colobus (procolobus badius), and Pennant’s colobus (Procolobus pennantii).

Because of its relative lack of development, the RoC has historically experienced less deforestation than many other tropical forest-rich countries. However, an influx of palm oil interest and a growing timber industry may be poised to change this.

Indeed, GFW shows RoC’s tree cover loss has been trending upwards, with more hectares lost in 2014 than in any other year since measurement began in 2001. According to the data, the African country’s deforestation rate has doubled since 2000, with 43 percent of its clearing happening in its old growth forests. The data indicate this may not be a one-off situation. Between the beginning of 2015 and February 29, 2016, there were nearly 327,000 GLAD alerts in the country – around 40 percent of which occurred in the first two months of 2016.

Unlike the RoC, Indonesia has been experiencing mega development for decades, with much of its forests converted to plantations or farmland, or razed for timber. In 2012 alone, researchers estimated Indonesia lost 840,000 hectares of primary forest, giving it the dubious distinction of having the world’s highest rate of deforestation.

The effects of Indonesia’s land conversions were felt acutely this fall when vast wildfires burned uncontrollably across several islands. Massive loads of smoke were released the blazes, choking local communities and impairing the air quality in greater Southeast Asia. By October, as many as half a million people had reported haze-related illnesses, and between 15 and 10 million metric tons of carbon was being released into the atmosphere every day.

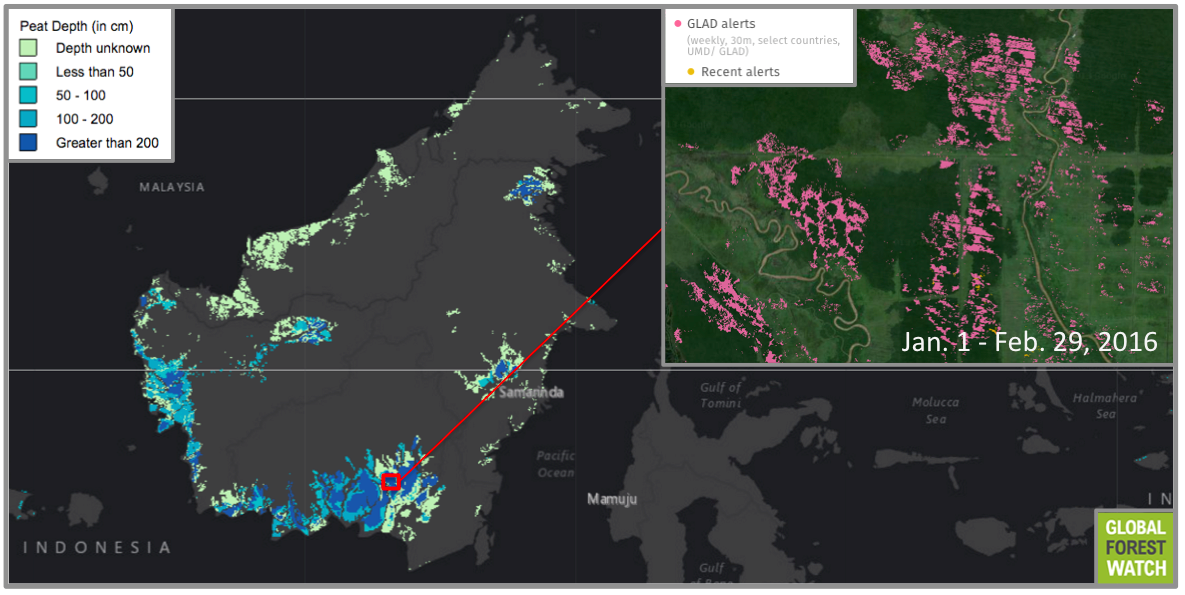

Kalimantan – the Indonesian portion of Borneo – is one of the archipelago’s most heavily affected islands. Home to endangered orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) and elephants (Elephas maximus borneensis), much of Kalimantan’s land area is now taken up by palm oil, wood fiber, and timber concessions. Many of these concessions are – or were – underlain by peat forest, which is too soggy to develop into plantations. To make it more suitable for industry, canals are carved into it, draining its water and drying its soil.

Once dried, peatlands are highly combustible. As if to illustrate this, more than half the fires that ravaged Indonesia this past fall occurred on peatlands, according to research by the World Resources Institute. They also contain among the highest concentrations of carbon on earth, which are released when peatlands burn and contribute to global warming.

In response to his country’s fire disaster, Indonesian president Joko Widodo expressed a desire for a stronger moratorium on peatlands development.

“We must restructure the peatland ecosystem,” Jokowi, as he is popularly known, told journalists in October. “I have instructed the environment and forestry minister to not issue any more permits on peatlands and to immediately begin revitalization.”

However, data from GFW indicate Jokowi’s sentiment may be lacking action on the ground, with several of Borneo’s deepest peatlands showing tree cover loss occurring in the first two months of 2016. In total, more than 1.5 million GLAD alerts have been issued for Kalimantan so far this year.

The new GLAD system could be a boon for forest management, write the analysts in their accompanying study, letting authorities keep an eye on tree cover changes without needing to develop their own remote sensing methods. And the system’s weekly alerts could help them to stop deforestation before too much damage has been done.

With just one day under its belt, MAAP researchers are already eager to use GLAD for their monitoring projects.

“In the coming weeks and months, we will use this map as a base for investigating major hotspots of forest loss in the country,” they write.

Disclaimer: Mongabay has a funding partnership with the World Resources Institute (WRI). However, WRI has no editorial input regarding Mongabay content.

– This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.