Scientists emphasize that reducing the threats of contagion by zoonoses depends on “landscape immunity”, but in Brazil, the maintenance of large conserved environments runs into loopholes and delays in implementing the Forest Code.

The acceleration of deforestation in the Amazon and other Brazilian environments has resumed in 2012 and has broken record after record during the Bolsonaro administration. At the time of publication, the country had over 625,000 Covid-19 deaths and 24.7 million cases according to official data. Scientists from American and Canadian institutions point out that containing environmental destruction reduces the chances of new pandemics.

Research published in the journal Conservation Letters highlights that the elimination and degradation of forests are major sources of transmission of zoonoses such as Covid-19, which initially reach people through insects or direct contact with wild and domestic animals. The research looked at cases of yellow fever and macular fever in Maranhão and other states. “Landscape immunity”, that is, the preservation of large conserved environments, is necessary to reduce possible threats of contagion.

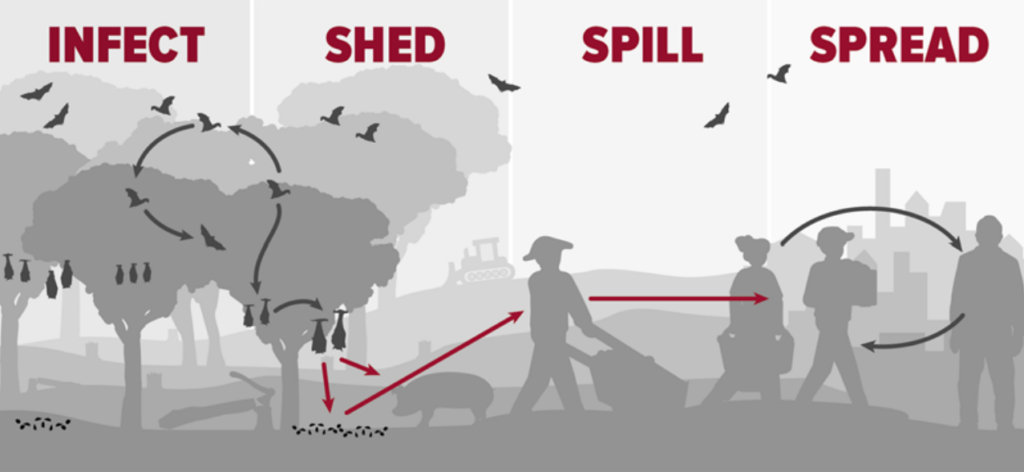

The spread of zoonoses and other diseases stored in natural environments is linked to deforestation, urbanization, infrastructure works, and other impactful actions. Without their usual habitats and predators, mosquitoes and animals are pushed out of the forests carrying viruses and other parasites that can infect people in rural and urban settlements.

“Preserved ecosystems are less likely to spread pathogens than those that have been destroyed or have undergone biological invasions, pollution, and other impacts. Thriving biodiversity maintains and strengthens the immune function of wild species and reduces the chances of human exposure to disease sources,” said Raina Plowright of Montana State University, one of the study’s authors.

Gary Tabor, a scientist at the Center for Large Landscape Conservation (United States), calls for greater attention to the impacts of deforestation and degradation within forests. “If we don’t pay attention to this stress, we will not realize the conditions we are creating to unbalance natural processes and increase risks of diseases spreading. Landscape immunity should be a criterion for the maintenance of healthy habitats,” he emphasized.

Preserved ecosystems are less likely to spread pathogens than destroyed ones. Thriving biodiversity maintains and strengthens the immune function of wild species and reduces the chances of human exposure to disease sources

Raina Plowright, professor at Montana State University’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

Given this scenario, he expects tropical countries such as Brazil to contain deforestation effectively and value the benefits of forests, including their role in stopping diseases and keeping the global climate under control. The measure was defended by the environmental ministers of the G7, the group of the richest countries on the planet, last May. Tabor recalled that the 200 largest multinationals in the world are adopting sustainable and regenerative practices to sustain their economic results, and hopes public authorities adopt similar measures.

“The world needs courageous leaders to help governments take effective measures to deal with environmental issues while also enabling community efforts to address the combined threats of biodiversity loss and climate change,” said the researcher, one of the authors of the study published in Conservation Letters.

ACTIONS TO INCREASE LANDSCAPE IMMUNITY

– Using land and other natural resources in a sustainable way

– Improving networks and connectivity between protected areas

– Gaining in-depth knowledge about the health of natural environments

– Reducing lawful and criminal hunting, trade, and consumption of wild animals

– Reducing large-scale cattle ranching

– Reducing the displacement of human populations

Scientists list actions so that each country can increase the immunity of its landscapes. Using land and other natural resources sustainably, improving the connectivity between protected areas, and gaining in-depth knowledge about the health of natural environments are strategic policies in this sense. Reducing the legal and criminal hunting, trade, and consumption of wild animals, large-scale cattle ranching, and the displacement of human populations are measures that also reduce the chances of contamination.

The challenges to adopting such measures grow in Brazil due to the disrespect to national parks, indigenous lands, and other protected areas. In the Amazon, deforestation in protected areas grew 79% over the first three years of the Bolsonaro government (2019 to 2021) when compared to the previous three years, as demonstrated in an analysis by the Socio-environmental Institute (ISA). In addition, the implementation of national legislation that would protect native vegetation in private properties is under attack almost a decade after the law’s enactment in May 2012.

A summary of 2021 by the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), a collective of experts linked to the PUC University at Rio de Janeiro that analyzes public policies and finances, shows advances in the registration of rural properties as required by law, but serious delays in the validation of records for fraud and failures to fill in the information, as well as difficulties in contact with landowners and claimants. Thus, agreements for the recovery of native vegetation in numerous rural properties remain stuck.

There is a greater interest of producers in compensating for vegetation recovery in other places than in restoring their own areas. There is a lack of landscape planning to foster the connectivity of legal reserves and permanent preservation areas.

Cristina Leme Lopes, Climate Law and Governance analyst at the Climate Policy Initiative

“The Forest Code took a long time to get off the ground. Its regulation was slow, federal and state governments were not exactly aware of the technical and financial challenges to implement the law, and unconstitutionality lawsuits took some time to be judged by the Supreme Court “, said Cristina Leme Lopes, Climate Law and Climate Governance analyst at the CPI. The Supreme Court only judged cases on aspects of the 2012 forest law in 2018.

In the Amazon, the implementation of the national forest law has advanced in Acre, Rondônia, Pará, and Mato Grosso, but recovering vegetation is more difficult in the face of economies focused on agribusiness. “There is a greater interest of producers in compensating for the recovery (of vegetation) in other places than in restoring their own areas. There is a lack of landscape planning to foster the connectivity of legal reserves and permanent preservation areas,” highlighted the specialist.

Thus, gaps and delays in the implementation of the law increase the chances of changes in legal deadlines for the vegetation recovery in private properties and hinder the maintenance and recovery of conserved landscapes with forests and woods on the banks of springs and rivers and other areas of social and environmental importance, which are more resistant to the spread of diseases.

“Permanent preservation areas are ecological corridors in the landscapes. The recovery of legal reserves close to other preserved areas should be proposed. This is more feasible in the Amazon than in other, more degraded biomes. It is strategic to recover natural vegetation to reconnect protected areas, ensuring groundwater recharge and a range of other environmental services,” said CPI’s Cristina Lopes.

Story by InfoAmazonia for the PlenaMata project.