In the rural area, the challenge for residents affected by the smoke is to get medical care

Fire in Poconé, Pantanal region of Mato Grosso, 2020

Photo: Juliana Arini

“Patient in very serious condition. Intubated yesterday with respiratory failure, breathing by mechanical means (ventilator), sedated, needing intravenous medication to sustain blood pressure, remains under intensive care”, states a hospital record in Cuiabá.

The life of Tânia Silva Moreira, 33, had been at risk since 5 August 2020. The former supermarket worker arrived at the Júlio Muller University Hospital, in the capital of Mato Grosso, in pain and having difficulty breathing. Nine months pregnant, she had to have an emergency caesarean to minimize risk to the baby. After giving birth, she returned to the quilombola [maroon] community of Mata Cavalo in the Pantanal, between Nossa Senhora do Livramento and Poconé, fifty kilometres from the capital Cuiabá.

tânia silva moreira

quilombola, 33, member of the maroon community of Mata Cavalo

The fires that had affected the whole of Mato Grosso similarly gave the residents of Mata Cavalo no respite. All the pasture on the smallholding where Tânia’s family lives had burned, and the property’s few animals were left without food. Breathless once again, she had to be taken once more to the emergency room. At the health post where the medical record that opens this text was written, she was intubated as a matter of urgency.

“Two tests detected Covid-19. I had severe acute respiratory syndrome and 100% of my lung was affected. I still have difficulty breathing. I needed physiotherapy and I still feel very weak. It took me six months to give my daughter, now ten months old, a bath. I was so weak that when I picked her up for the first time, I almost dropped her”, says Tânia, who also suffers neurological after-effects from the virus contracted a year ago.

Two tests detected Covid-19. I had severe acute respiratory syndrome and 100% of my lung was affected. It took me six months to give my daughter, now ten months old, a bath. I was so weak that when I picked her up for the first time, I almost dropped her.

Tânia Silva Moreira

hospitalized in the state capital, had to undergo an emergency caesarean operation

In August 2020, the month in which this Mata Cavalo resident was hospitalized in a serious condition, Mato Grosso was the state with the third highest number of fires in Brazil. Between the beginning of August and the beginning of September, more than 88,000 heat sources were detected by images from the S-NPP/VIIRS satellite, monitored by the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and used for the InfoAmazonia analysis. In the thirty days prior to this, sensors in space had detected just over 10,000 outbreaks.

The large number of fires released a lot of toxic particulate matter into the atmosphere, a process that increased the number of hospitalizations for respiratory syndromes by 62% and the cases of Covid-19 admitted to hospitals in the state in September by 46%. On average between July and October, these rates were 32% and 24% respectively.

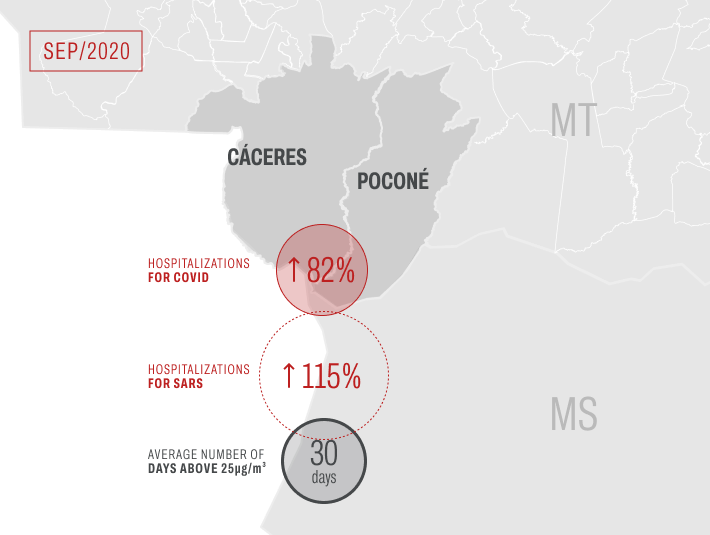

Air pollution and increase in Covid hospitalization between July and October 2020

On the map, hover the mouse over the circles for data on particulate matter and hospitalizations for Covid and SARS in municipalities of Mato Grosso state.

The InfoAmazonia analysis reveals that Poconé is top of the list of municipalities with the greatest increase in hospitalizations linked to particulate matter for the whole burning period. In September, the worst month, residents of Poconé and neighbouring Cáceres lived with an 82% greater chance of being admitted to hospital with complications from Covid-19 and a 115% greater chance when considering all respiratory syndromes attributable to burning. The air in both places was saturated with particulate matter for the entire thirty days of the month.

Poconé had the largest increase in hospitalization rates

Source: InfoAmazonia analysis

The municipal secretary of environment, Danielle de Assis Carvalho, 31, is one of the lives that reveal the tragedy of statistics. In addition to being hospitalized with respiratory problems, she lost a child at the beginning of her pregnancy in 2020. On the front line of the firefighting, she fell ill at work. “It was in September, at the height of everything. Fire, heat, drought, and smoke. One day I passed out and ended up in hospital. That’s when I found out I was pregnant and worse, that I had already lost the baby. I had to stay in hospital for seven days unable to breathe properly”, Danielle recalls in tears.

danielle de assis carvalho

Municipal Secretary of Environment of Poconé, 31

It was in September, at the height of everything. Fire, heat, drought, and smoke. One day I passed out and ended up in hospital. That’s when I found out I was pregnant and worse, that I had already lost the baby.

danielle de assis carvalho

Environment secretary who took part in fighting the fires that destroyed the Pantanal

According to the environment secretary of Poconé, the serious fires that ravaged the Pantanal in 2020 changed the city’s routine. “I used to travel all the time to Porto Jofre [a district of Poconé, where the Transpantaneira Highway ends], where the smoke was more intense and so was the heat – the Encontro das Águas (Meeting of the Waters) State Park, which has the largest population of jaguars of the world, lost 82% of its original area – to support the firefighting, help sort out vehicle breakdown problems, and even take firefighters to remote regions. In the end, my body and my baby couldn’t stand it”, says Danielle, who is now at the beginning of a new pregnancy and fears that the fires will hit the Poconé region once again in 2021.

Fires in August 2020 along the Transpantaneira highway (MT-060), Poconé, Mato Grosso

Photo: Juliana Arini

According to public health researcher Tatiane Moraes, from the Fiocruz Climate and Health Observatory and one of InfoAmazonia’s scientific data analysis consultants, the situation in Mato Grosso in 2020 reveals a serious picture that the pandemic has helped to bring into sharper focus. “These are regions where populations have longstanding unmet demands for health services. In addition, the quality of environmental surveillance systems, that should provide alerts and monitoring, is low. From a macro point of view, the presence of Covid made the situation even more complex”, says the researcher.

These are regions where populations have longstanding unmet demands for health services. From a macro point of view, the presence of Covid made the situation even more complex.

tatiane moraes

public health researcher, Climate and Health Observatory, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation

However, according to Tatiane, although the consequences may be the same, and the rationale may apply to those areas of the Amazon most impacted by the negative synergy between fire and an increase in hospitalizations, the causes may differ. “It is not always the same process that explains the burning throughout the entire Amazon region. There are different environmental scenarios – there are agriculture, mining, and other activities”, says the Fiocruz scientist.

The example of the Pantanal in 2020 shows this well. The biome was affected by the worst burning season in the region’s history. The fire affected 26% of the biome, according to a study by the Laboratory for Environmental Satellite Applications (LASA), of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, an area slightly larger than that of Switzerland. According to surveys and official data, the fires originated from human activities, on private ranches. According to data from the Instituto Centro de Vida (ICV), 55% of the hot spots detected in August 2020 were on rural properties that had been self-declared under the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR). The origins of the fires that affected more than 82% of the Encontro das Águas State Park and the SESC Pantanal Private Natural Heritage Reserve (RPPN) originated predominantly from such private properties. Across Mato Grosso, a state that is part of the Legal Amazon region, fires also destroyed areas within the Amazon biome.

82% of the area of the Encontro das Águas State Park was burned in 2020

Source: coloured composition of Sentinel-2 satellite images, European Space Agency (ESA)

An acute environmental crisis, such as that of 2020, leads to another problem. Health networks are fragile, particularly in the interior of Amazonian states. In the case of cities such as Poconé, Nossa Senhora do Livramento and Barão de Melgaço, where the rural population is greater than the urban, the difficulty in accessing adequate health care is an everyday reality.

sônia maria

resident Jejum community, 53

Sônia Maria, 53, resident of the Jejum community in Poconé, lost her 78-year-old sister-in-law and neighbour to Covid-19. Where Sonia lives is more than forty kilometres from the municipal seat. The nearest health post to where she lives with her 72-year-old husband and a mentally handicapped son is a family health clinic in the district of Cangas. Even this is twenty five kilometres away.

“We save up and take a taxi when we can. It’s R$50 to go and another R$50 to come back. When a neighbour is willing to share, it costs R$30 each. We need to take the boy to Poconé all the time. We survive on a pension of one minimum salary and from the sale of the string rugs I make. There’s no way we can go to town twice in the same month“, says the home maker. She says she picked up Covid in 2020 but looked after herself at home. “Last year was very difficult because of health, but we stayed here trying to get better with home remedies. We are very afraid of Covid, a lot of people have died around here from this disease, but there’s nothing we can do”, she says in resignation.

We save up and take a taxi when we can. It’s R$50 to go and another R$50 to come back. There’s no way we can go to town twice in the same month.

sônia maria

housewife, quilombola [maroon] community of Jejum, Poconé, 25km from the nearest health clinic

The problem of getting to the nearest health centres is both chronic and widespread, says Edson Batista da Silva, a local health worker. Although quilombolas have all received both doses of the vaccine against the new coronavirus, explains Silva, the pandemic is still claiming victims in 2021. “Before the second dose, two very healthy quilombolas died from Covid, we can’t risk it, but the lack of transport makes everything very complicated”, he says.

In the municipality of Nossa Senhora do Livramento, the ambulance will only take patients from the city to the state capital. “Not even doctors want to work in the most distant communities; we are without a doctor now, the last one resigned. In 2020, many sick people took refuge in their homes, because they had no way of getting help. With this drought and fires arriving sooner, I don’t know what the people of the Pantanal will be able to do to fight Covid this year”, the health worker says.

Not even doctors want to work in the most distant communities; we are without a doctor now, the last one resigned. In 2020, many sick people took refuge in their homes, because they had no way of getting help.

edson batista da silva

public health worker, Nossa Senhora do Livramento

Often the only means of escape in the fight for survival is if the patient manages to get to the former municipal first aid centre of Cuiabá, now the Covid-19 reference hospital for the state. According to nurse Ademilson Pereira da Silva, the period between July and August is always the most worrying. Last year, the situation became even more tense because, with so many cases arriving, it was even difficult to separate those suffering from the new coronavirus infection from other types of respiratory problems, which can also lead to death. “We receive patients from other towns in Mato Grosso, mainly from the Baixada Cuiabana region and the Pantanal [where Poconé is located]. We had a triage room where we had to separate those who had respiratory problems often caused by other viruses from those who had Covid”, recalls Ademilson.

“The months of fires and no rain are always the most difficult. Primary health posts in the different regions receive the sick. Everything starts there: runny nose, asthma, and bronchitis. When the person gets weaker and gets infected with Covid-19, they come here”, says the nurse. According to Ademilson, the long saga of seeking treatment, especially from the most remote areas, greatly affects the chances of survival. “The delay makes the person arrive at the reference hospital very debilitated”, he says.

seo josé palma

Santa Luzia community, 57

The lack of rain continues to concern the Pantanal region in 2021. Small farmer José Palma, 57, needed to sink his well deeper to get water for his family and save his banana crop, typical of the region. “We dug deeper down and found water, but we don’t know for how long; it’s not supposed to be so dry,” says the farmer, who hasn’t got over his memories of 2020. “I’ve never seen the Pantanal burn like that. Everyone got sick here at home. My ten-year-old grandson (Christopher de Souza) was coughing. The worst was my niece, Carmem Palma, who later caught Covid. She was in hospital for two weeks with this disease. It was very difficult. We suffered with the smoke; we saw the animals suffer and couldn’t do anything”.