The Guardians of the Forest, a group of indigenous Guajajara in the Brazilian state of Maranhão, struggle to defend their land from invaders and to guarantee their survival in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

By Manuella Libardi

If we ask Olimpio Santos Guajajara when the Guardians of the Forest were founded, his answer would be very simple: in 1500, the year the Portuguese landed in Brazil with an army under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral. This indigenous group, which protects what is left of the Amazon forest in the state of Maranhão, in the northeast of the country, was officially established in 2013, but for the Arariboia Guajajara that date represents only the formalization of a struggle to which they have already dedicated more than five centuries.

The Guardians of the Forest are a group of 120 indigenous activists who are trying to protect the 413,000 hectares in Arariboia against environmental crimes, which are perpetrated almost always by illegal loggers. This territory, located in southeast Maranhão, is home to nearly twelve thousand members of the Guajajara, Awá-Guajá and Awá people. Some of the latter are uncontacted. The Guajajara are the ones primarily responsible for protecting this land and also account for most of those who have been killed doing so.

Their work is grueling and dangerous. In the last 20 years alone, 49 members of the Guajajara people, who call themselves the Tenetehar, were killed in armed conflicts with loggers in Maranhão. This is according to a report by the Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples (CIMI). Researchers say there have been 44 instances of invasion involving illegal use of the land since 2006, including 20 in the last six years, which makes Arariboia by far the indigenous territory in Maranhão that is most affected by violence.

For the Guajajara, saving their land is an ancestral duty. Olimpio Guajajara, who is 46 years old and the leader of the Guardians of the Forest, insists his involvement in the group began the moment he was born. “My great-grandfather was a famous warrior in our territory. I have been a Guardian since birth,” Olimpio said by telephone.

The image of an Indian warrior is part of Brazil’s collective imagination. The history books tell stories of leaders such as Cunhambebe and Aimberê (Tupinambá), and Arariboia (Temiminó), heroes in the bloody battles with Portuguese and French colonizers for control of the land around Guanabara Bay, in the state of Rio de Janeiro. These conflicts defined Brazil’s destiny in the 16th century. Stories of the brave Guaicurus, an indigenous group that originated in the Pantanal and appropriated Portuguese technology and horses to terrorize the invaders, have spread to the far corners of the country through oral tradition. In fact, these stories still have a great deal of influence on pop culture. For example, Papa-Capim, a character in the Turma da Mônica comic book series by cartoonist Maurício de Sousa, dreams of growing up to become a great warrior of his tribe.

Olimpio Guajajara and the Guardians of the Forest are a living legacy of the struggle of Brazil’s indigenous people, who are dedicated to caring for a natural heritage that should be everyone’s priority. Unfortunately, they stand virtually alone against their enemies: loggers, police who ignore the problem, and politicians with an agenda bent on exploiting natural resources. And, as if that were not enough, they now have to struggle with the devastating effects of COVID-19.

Who are the Guardians of the Forest?

The Guajajara began discussing the possibility of formalizing the Guardians of the Forest in 2007, following the death of Tomé Guajajara, a 60-year old leader tribal leader. According to information from CIMI, he was murdered on the morning of 15 October 2007, when fifteen armed men invaded the village of Lagoa Comprida, in the municipal district of Amarante do Maranhão. Tomé died after being shot six times by one of the invaders, when trying to fight them off. They left two others wounded: Madalena Paulino Guajajara, who was shot in the neck, and Antônio Paulino Guajajara, who took a bullet in his right arm.

The elders of the villages in the indigenous territory of Arariboia met with the younger ones to ask them to take responsibility for defending the community and its land, without waiting for public authorities to act. Six years later, in 2013, an assembly of the Guajajara people formally established the Guardians of the Forest.

“The work they do is crucial. If it were not for them, I believe the forest that is still left in Arariboia would no longer exist,” says Gilderlan Rodrigues, who coordinates the Maranhão Regional Division of the CIMI. “They managed to reduce the [number of] invasions, which are still frequent, but far less than before. They also lent visibility to their struggle in the outside world. They are going to preserve the land for future generations, who will be able to grow up and feed themselves and learn about the animals, the rituals and the culture of their ancestors,” he said.

The rounds are conducted on the perimeter of the area, by groups of at least five people, but usually with many more. Some of the rounds are completed in a few hours, but normally they can last for days. As shown in the photos sent by several Guajajara leaders, long distances are patrolled on foot, but also with the help of motorcycles and motorized quads. Following an ancestral tradition, many of the Guardians paint their faces red, using dye extracted from seeds found locally, such as annatto. Others prefer to cover their faces with hats to avoid being identified.

After gathering evidence of invasions, the Guardians decide which parts of the territory require more frequent surveillance and try to locate the roads and highways used by trucks to move logs out of the forest. According to the most recent data obtained by the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), 1,248 kilometers of roadway were opened for illegal logging operations in Arariboia between September 2018 and September 2019.

One of the objectives of the Guardians of the Forest is to find illegal logging camps and seize equipment used to extract timber, such as motorcycles, tractors and chainsaws. The group says the items they seize are turned over directly to the authorities, as evidence of criminal activity. Sarah Shenker, an activist and researcher with Survival International, a British human rights organization, accompanied the Guardians of the Forest to an illegal camp during one of these operations. It was empty, but the smell of food indicated the illegal loggers had just left. These encounters between the Guardians of the Forest and illegal loggers often end in death.

“Despite the danger, they know no one will protect Arariboia if they do nothing. The survival of an entire village is at stake,” Sarah said in March of this year, referring specifically to the Awa, a village that remains isolated from contact with the outside world and occupies three percent of the area protected by the Guajajara. The village has just under 100 people. Accordingly, the work of the Guardians of the Forest involves more than safeguarding the forest and its resources. It also includes protecting the group classified by Survival International as the one that is “most threatened in the world.

“To defend our land is to defend our people,” says Laércio Souza Silva, a 34 year old man who is known to his people as Tainaky Tenetehar and is also a member of the Guardians of the Forest. As a child, he listened to the older men talk about the threats they experienced. For the Guajajara, defending their territory also means defending their people and their culture. “We don’t want our history to end here,” says Tainaky.

“These are our warriors, our heroes,” says indigenous leader Cintia Maria Santana da Silva, or Cintia Guajajara, as she is known in her community. According to her, deforestation and fires are the most disastrous consequences of the attacks on her territory. The struggle the Guardians are waging in the forest is being continued by Cintia in the academic world. She has a master’s degree in Linguistics and Indigenous Languages from the National Museum of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. She is also Deputy Coordinator of Articulation of Indigenous Women of Maranhão, an advisor to the Union of Indigenous Women of the Amazon, and Brazil’s representative to the Coordinating Committee of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin. “If we do not defend our land, where do we go? We don’t want big projects. We want health and education, and our “uniqueness” to be respected.

Who are the Guajajara?

According to the Office of the Special Secretariat on Indigenous Health, which serves the Ministry of Health, there are currently about 27,000 Guajajara. Concentrated in the state of Maranhão, they are one of the most numerous indigenous groups in Brazil and belong to a broader group that calls themselves the Tenetehar, also written Tenetehára, which includes the Tembé in the neighboring state of Pará.

The Guajajara language belongs to the Tupi-guarani family and they call it ze’egete, which means “the good talk”. Guajajara means “owners of the headdress” and Tenetehar means “we are the true human beings,” as indicated by the Brazilian Indigenous Peoples Program (PIB) of the Socio Environmental Institute. The mother tongue is spoken in all Guajajara villages, while Portuguese serves as the lingua franca.

This is the “uniqueness” that is so cherished by Cintia Guajajara and has been under attack for several centuries, as Olimpio Guajajara explained. The Guajajara probably first made contact with non-indigenous people at the beginning of the XVII century, although the information in that respect is not very precise. As noted by Dr. István Van Deursen Varga, a researcher who wrote an article that appeared in 2008 in Acta Amazónica, a scientific journal published by the National Institute of Amazonian Research, there is an account of a chance meeting between the Guajajara and a French exploratory expedition on the banks of the Pindaré River in Maranhão, which occurred before the capital of the state, São Luís, was founded in 1612.

Research shows the expedition returned with “news of a large indigenous nation they called the ‘Pinariens.’” In 1615, the Portuguese expelled the French from the region and, the following year, they launched a similar expedition to the homeland of the Guajajara. They were looking for gold and slaves. So began a long period of conflict. “Fleeing initially from the Portuguese slave hunters, from the landowners and lords of the sugar mills and, finally, from the servility and control imposed on their villages by the Jesuits, some of the Tenetehara migrated to the dense forest of the west (the Tembé), while others continued to occupy the valleys and the interfluvial routes between the Mearim and Grajaú rivers (Guajajara), thus exposing themselves to the consequences of early coexistence with the continuously expanding frontlines of the dominant society,” writes István.

After the Jesuits were expelled from Maranhão in 1759, the Guajajara managed to recover some of their former independence, but became the target of an intensive policy of miscegenation (mixing of races).

Arariboia Indigenous Land: The Green Island

In Maranhão, 76 percent of the original Amazon rainforest has already been devastated, as indicated in a study published in Land Use Policy, which is a scientific journal. According to the researchers who were involved, Maranhão no longer has any virgin forest outside the sixteen original indigenous territories controlled by the National Indian Foundation. With 413 thousand hectares, Arariboia is the second largest territory in the state, preceded only by the Alto Turiaçu reservation, with 530 thousand hectares. However, it is by far the most populated and, therefore, has the most human lives at risk.

“Arariboia is a green island amidst a sea of deforestation. The Guardians are risking their lives to protect what is left of the forest in this part of Maranhão,” explains Sarah Shenker of Survival International.

The economy in many of the cities around Arariboia was based historically on extractive industries, mainly logging. With the degradation of unmarked land, local loggers see indigenous land as a gold mine. “The Guajajara are on land that includes what is left of the Amazon. So, the area has a lot of wood and it sparks an interest,” says CIMI’s Gilderlan Rodrigues. Arariboia has an abundance of trees with high market value, such as zabucajo, angelim, ipé, cumarú, jatobá, copaíba and cedar (also known as acaiacá).

The Guajarara subsist mainly through farming, as explained on the PIB website by anthropologist Peter Schröder from the University of Pernambuco. Yucca, yams, corn, rice, pumpkins, beans, avas, caras (an Amazon fish) and bananas are the most common foods in Arariboia. According to Olimpio Guajajara, they are the bedrock of indigenous health. Farming is done in two stages: “In the dry season, from May to November, they till, cut, burn and clear, while planting and weeding are done from November to February,” wrote Peter Schröder.

Hunting continues to be an important activity for the Arariboia Guajajara, says Olimpio. However, as Peter Schröder notes, it has become less productive in recent decades, due to competition from non-indigenous people and the limitations of land. Hunting was further complicated by the wildfires in 2015, which burned nearly 200,000 hectares in Arariboia – about 50 percent of the territory – and devastated the mammal and bird populations. Hunting declined as a result. But Olimpio says it is returning to Arariboia, little by little. Giant armadillos, gualacates (yellow armadillos), anteaters, opossums, sloths, penelopes (bird), muitu turkeys, peccaries and monkeys are among the animals most commonly found in the area.

Other customary forms of livelihood are fishing and gathering honey and fruit, says Sarah Shenker. According to her, some Guajajara exchange and sell farm products. Handicrafts are produced as well and sold mainly to non-indigenous customers.

The extent of access to formal education is far from ideal. There are government schools in every region of Arariboia, but not in every village, explains Sarah. Some schools were not operating even before the pandemic, forcing children to go to another village to study, or to attend schools with non-indigenous students. Violence, however, remains the main problem for the local indigenous population.

Traces of Blood in the Forest

In Maranhão, the struggle to defend the land, the culture and the people is marked by death. According to data from the Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples, 49 Guajajara were murdered in the state between 2000 and 2020 as a result of conflicts with loggers. Eighteen of these crimes were committed in Arariboia, and four Guajajara were murdered in the last two months of 2019.

One of the recent victims was 26-year-old Paulo Paulino Guajajara, who was also known as Kwahu Tenetehar, which was his indigenous name. According to several Guajajara leaders, Paulo and Tainaky Tenetehar were hunting with bows and arrows in the area of Bom Jesus das Selvas, inside Arariboia, on 1 November 2019 when they were ambushed by a group of five men. Paulino was shot in the neck and died. Tainaky was wounded by a bullet that hit his right arm and ribs, but he managed to survive.

The case received a great deal of attention in the media and there were international repercussion. Yet, it was not enough to break the cycle of impunity that prevails in cases of violence against indigenous people. The Federal Police prosecuted two suspects for intentional homicide in January 2020, but both remain at large.

According to CIMI data compiled between 2006 and 2019, there were 20 registered cases of land invasion in Arariboia. In all, there were 44 cases in areas where members of the Guajajara community also were reported to have been murdered. Almost half (20 invasions) occurred in the last five years. “The certainty of impunity and lack of oversight by the respective authorities added to the violence,” says CIMI’s Gilderlan Rodrigues.

Jair Bolsonaro and the Challenges of covid-19

Not much help is expected from the federal government. President Jair Bolsonaro (an independent) was elected with a great deal of support from the agribusiness community. In July of last year, he went so far as to say “this government is yours,” when addressing members of the Parliamentary Front for Agriculture, as reported in O Estado de S. Paulo, a Brazilian newspaper. On the other hand, he makes no secret of his aversion to indigenous groups, who are protected by the Brazilian Constitution of 1988. There have been decades of controversial statements in this respect.

The first example of this systematic rejection of the indigenous cause was in a statement Bolsonaro made on 15 April 1998 when he was still a federal representative. He was quoted in the Official Journal of the House of Representatives as having said: “The competent ones were the soldiers of the US cavalry who annihilated their Indians in the past, and now the problem doesn’t exist in there.” This was followed by other statements, in a similar tone. “I’m not part of the lie about defending the land for the Indian,” he told Campo Grande News in April 2015, after being honored by the General Command of the Military Police in Mato Grosso do Sul.

In April 2017, while campaigning for president, he made it clear what he would do if elected. “Not an inch will be marked out for indigenous land or for the Quilombolas,” he said, according to O Estado de Sao Paulo. After being elected president, he maintained his position: “No doubt, the Indian has changed; he is evolving. More and more, he a human just like us,” he said on 23 January 2020, according to UOL, a media company in Brazil. Olimpio Guajajara claims Bolsonaro “is responsible for a cold war against my people and against all Brazilians.”

As if their flesh and blood enemies were not enough, the novel coronavirus pandemic became a new adversary, with the Amazon region being one of the most affected in the country. By 11 September 2020, there were more than 31,300 confirmed cases of the disease among Brazil’s indigenous population and at least 793 deaths, with a total of 158 groups affected. This is according to data from Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil.

Gilderlan Rodrigues maintains it is difficult to estimate how many cases there are in Arariboia, mainly because there has been very little testing for COVID-19 among the local population. He also says there were six deaths from COVID-19 in indigenous territory and 80 confirmed cases by the end of August, but he estimates the number to be much higher. After the outbreak reached Maranhão, the indigenous community organized in an effort to block the access routes leading into Arariboia, so as to protect the villages. “The Special Indigenous Sanitary District did not do its job,” adds Gilderlan, referring to the Ministry of Health unit responsible for implementing health policies in indigenous areas. “It didn’t come up with a contingency plan. It failed to create specific place where the indigenous community could be treated. It did a minimum number of tests compared to the demand, and if it wasn’t for the initiative of the Indians themselves, the situation might be very different.”

“The Special Indigenous Health Department (Sesai) units of the Ministry of Health do not get the resources they need for indigenous health care,” says researcher Sarah Shenker. “So, there is a terrible shortage of medicine, doctors, nurses and ambulances. Only a few villages have health posts to deal with minor problems. There are Sesai health centers in some cities that share land with the Arariboia indigenous territory, such as Amarante do Maranhão and Arame. In the city of Imperatriz, about 200 kilometers from indigenous territory, there is an Indigenous Health Center for more complex procedures.

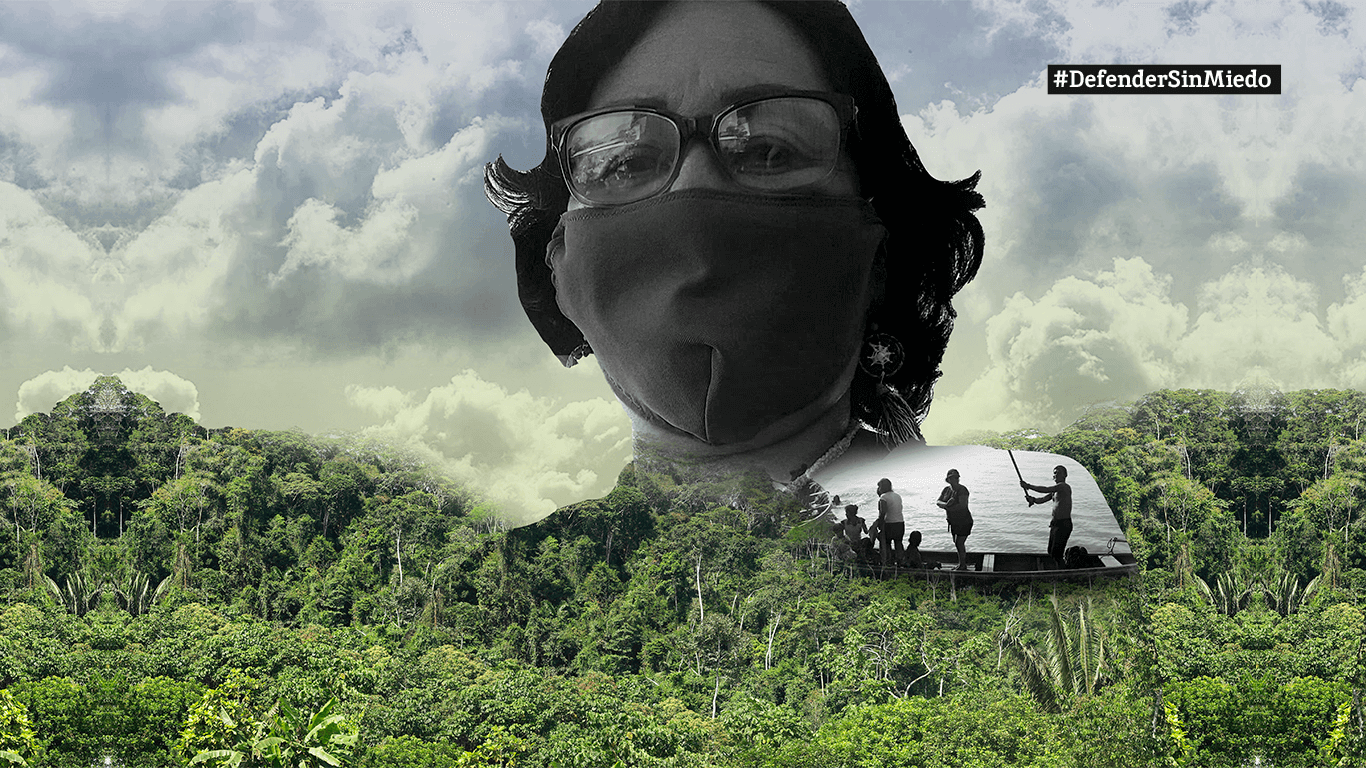

To avoid further contagion, Olimpio Guajajara and the Guardians of the Forest reduced the frequency of their rounds, relying more on exchanging information remotely, mainly through the WhatsApp messaging application. When necessary, small groups patrol the territory, covering their noses and mouths with protective masks. In July, at the height of the pandemic, there was a clash between the Guardians and the loggers, fortunately without victims.

From the enemy trenches, there is no sign of retreat. The extent of deforestation the Brazilian Amazon increased by 34.5 percent between August 2019 and July 2020 with respect to the previous 12 months. It is the highest rate in the last five years. Then again, as the Guardians of the Forest say, their fight has been for the right to exist ever since the Portuguese landed on the northern coast of what is now Brazil and named it after Brazil wood, a prized tree on the European market at the time and a species that is now threatened with extinction. For them, defending the forest means fighting for a future. “We will continue to confront the wrongs committed by the Brazilian system of justice against the lives of Brazilians,” says Olimpio Guajajara. “We are the great defenders of the lungs of the Earth, which serve the entire world: its grandchildren, great-grandchildren, great-great-grandchildren and all their descendants”.

(Translation: Sharon Lee Navarro)

This article is part of #DefendWithoutFear, a journalist series that tells the stories of women and men who struggle to defend the environment in a time of pandemic. Developed by Agenda Propia, in coordination with twenty journalists, editors and allied media in Latin America, the series is made possible thanks to support from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a global NGO.