Scientists analysed the Peruvian Inambari dam’s Environmental Impact Assessment to see if company ethics were driven by sustainability or profit.

Latin America’s largest electrical company operates 45 hydroelectric dams, and is responsible for 34 percent of Brazil’s generating capacity. The company, Eletrobras, makes laudable claims about its corporate values, including a commitment to sustainability, and to “operating through a well-balanced environmental, social and ethical responsibility.”

But with grave concerns raised about the environmental and social impacts of hydroelectric dams in the Amazon, and with Eletrobras itself a key actor in the hugely controversial Belo Monte dam, how sustainable are dam-building companies really being? Are the business decisions they make driven by a genuine commitment to sustainability? And, perhaps more importantly, how can we pragmatically assess the true motivations behind those decisions?

Ethical analysis may hold the answers, according to a recent study published in Sustainability. An international team of researchers suggest it is possible to pinpoint what lies behind a company’s decision-making process through a rigorous ethical analysis.

The analysis process began by identifying a hypothetical course of action that would most benefit a company financially, then it measured that approach against defined ethical principles, and finally compared those values with the actual course of action a business took in a real world project.

Put simply, if the actions of a business go above and beyond maximizing the financial bottom line, and are in line with ethical principles, this would indicate that the company in question takes issues such as sustainability seriously. What’s more, the researchers argue that if companies actually incorporated this kind of ethical analysis into their decision-making process, it could end up promoting better sustainability and environmental practices.

“We suspect that doing the analysis will alter the decision, and our hope is that it would help companies take decisions that are closer aligned with broader societal goals,” said two of the researchers, Julian Rode, an economist at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research–UFZ, Germany, and Marc Le Menestrel, a professor of ethics in business decisions at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain.

Ethics in action

The team chose the Inambari dam in the Peruvian Amazon as its real world case study. If it had been built, the dam would have flooded 46,000 hectares (177 square miles) of rainforest and displaced thousands of people, but it was cancelled in 2011 after sustained opposition from local communities. Eletrobras was identified by the study as the “main strategic actor” in the consortium of Brazilian companies, known collectively as EGASUR, that were originally responsible for the project.

The team focused on the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) undertaken in preparation for the dam’s construction, seeing the EIA “as a key corporate decision with large sustainability implications.” It is the company seeking the EIA that employs the contractor to make the assessment.

The researchers began by defining a hypothetical financially motivated “minimalist EIA”: one that “is cheap and quick,” which minimizes a few negative impacts “and attributes low monetary values to them, while complying with current Peruvian law and avoiding a scandal.”

Next, two ethical principles were applied to this hypothetical, financially-driven EIA. Consequentialist analysis looked at the pros and cons for all affected entities, including the impacts of the dam on local residents, national welfare, and the global community. Deontological analysis examined the extent to which such an EIA would comply with existing moral norms and rules, such as laws, standards of financing institutions, and international good practice guidelines.

The researchers concluded that Brazil and EGASUR would benefit from such a financially-driven EIA, but all other groups would be harmed: negative impacts would be underestimated and mitigation measures would be insufficient for the environment and local communities. The EIA would also fall foul of a number of laws, recommendations, and principles of good practice.

The team then undertook research to evaluate the actual EIA that EGASUR had performed. They interviewed a range of people on the ground in Peru, including representatives from local communities, NGOs, regional government and the businesses involved. A picture emerged of a lack of trust, a feeling that EGASUR acted in secrecy, that many stakeholders were opposed to the project, and that the company employed by EGASUR to undertake the EIA had “neither… a mandate nor the incentives to perform an objective, independent study that incorporates and evaluates all potential impacts in the best interest of the affected population and the environment.” These factors would seem to indicate that the actual EIA was similar to the hypothetical minimalist EIA — based on financial gain rather than good ethical decisions of benefit to all stakeholders.

Examining the executive summary of the actual Inambari dam EIA, the team noted that compensation costs assigned by EGASUR were significantly higher than the company had previously estimated, at 80 million dollars for environmental compensation (2 percent of the total investment cost), and 150 million dollars for community relocation (a further 3.8 percent of the investment). However, the researchers found that, “Even though the estimated social and environmental costs are significantly higher than what one would expect from a minimalist study, [the actual EIA] clearly presents a biased perspective of the impacts and does not comply with most rules and principles that characterize international good practice.”

In addition, the Inambari EIA minimized “ the severity of impacts, in particular by underrating harm to the local population and nature,” the team said. “The analysis hence led us to the conclusion that the company does not regard sustainability concerns as necessary and appropriate reasons to act, but merely as an obligation that should be met with minimum effort.”

The project that won’t die

Although strongly opposed by environmentalists and impacted communities, and officially cancelled, the Inambari project is not yet dead — with the dam still listed as part of Eletrobras’ strategic agenda as recently as May 2015, according to the study.

The project’s current status remains unclear: “We heard mixed messages,” Rode and Le Menestrel told Mongabay. “On the one hand, the Brazilian companies for a long time seemed to continue ‘under cover’, with communication and lobbying activities, mainly targeted at Peruvian politics and at local population in the Puno region. But recently there was a press release saying that Eletrobras is reducing its project activities on hydropower in South America and Africa, and Peru is no longer mentioned as priority.”

The researchers speculate that a more ethical approach to the project might have proved financially beneficial for EGASUR. “Paradoxically, a wider perspective and a different approach, striving for sustainability, could have led to better consequences for the company,” the researchers said. “For instance, a broader EIA could have identified a different investment approach for energy generation in Peru altogether, say via smaller dams closer to the Andes. Completely hypothetical of course, but the point is that ethics can also help recognize new [economic] opportunities. Marc calls this ‘ethics as the art of surprise’”.

Bringing ethics to the dam decision making process

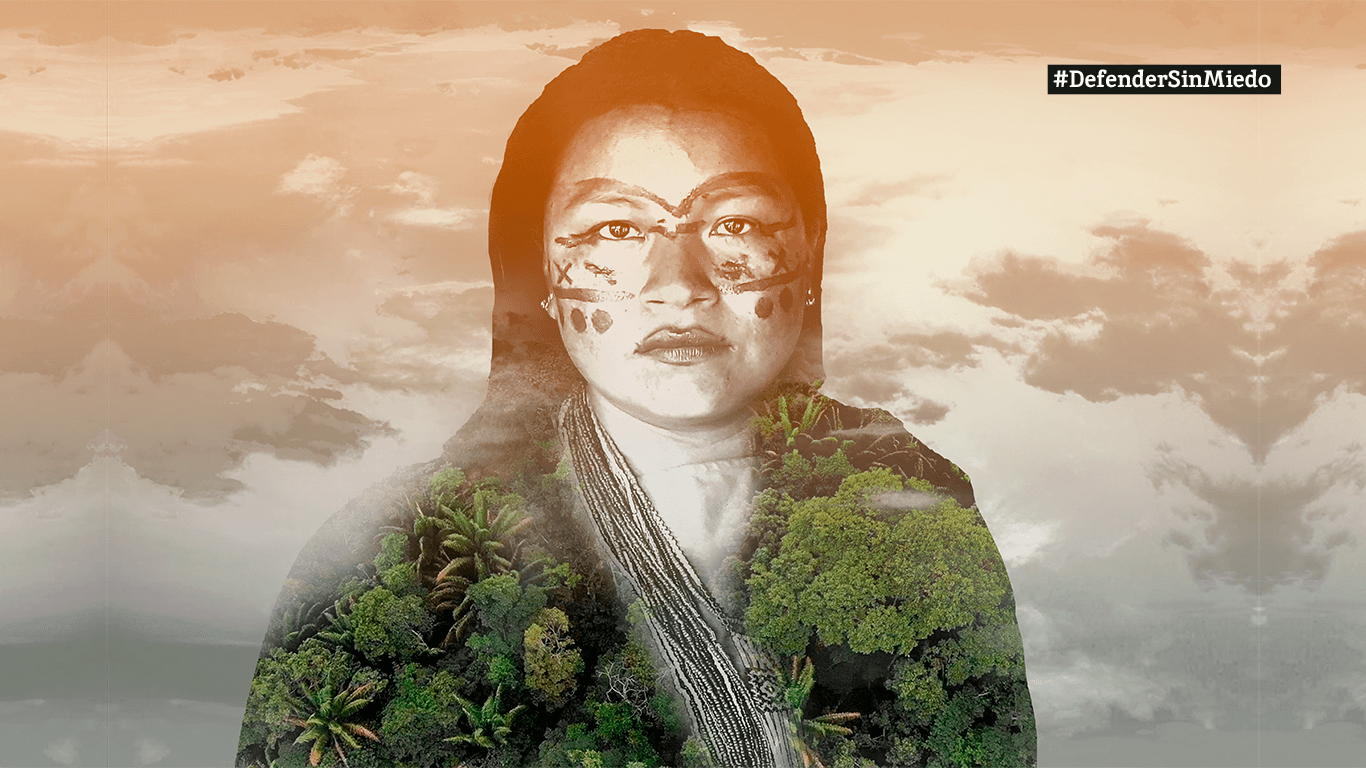

Within the broader context of hydroelectric development across the Amazon region — where hundreds of dams are in various stages of planning, construction, and operation — there is increasing concern about the harm these so-called “sustainable” energy projects are causing to both the environment and to indigenous people.

At the extreme negative end of the ethical spectrum, the Brazilian government and Norte Energia — a consortium of companies that includes Eletrobras — have been charged with ethnocide in the building of the Belo Monte dam — with seven indigenous groups impacted. The ever-widening Lava Jato corruption scandal also continues to unfold in Brazil, implicating some of the nation’s largest construction companies along with Petrobras, the nation’s biggest oil company.

Given the culture of corporate and political corruption in Brazil, the mismatch between the sustainability claims of large companies and the major harm they sometimes do to the environment and society, how could the situation be modified to benefit all stakeholders?

“A fundamental shift is needed in terms of corporate culture and mission, from financial objectives towards broader sustainability goals,” Rode and Le Menestrel told Mongabay.

One way of making companies more accountable, they explained, would be to impose mandatory ethical analyses on large infrastructure projects — analyses that would be conducted by independent authorities and available to the public. “We think that some political authority to frame and orient the rationality of business is needed to make them genuinely serve public interest,” said the researchers.

“There is no need for a revolution here,” they added. Society and government simply need to recognize “that economic institutions — and business in particular — are not structured to naturally serve the common good without appropriate regulatory power.”

“There is always some influence between politics and business,” the pair explained. “What is important is to check whether the institutional structures and processes are well-intentioned and transparent enough for that influence to have a chance to be ethical.” Without such institutional structures, the opportunities for secrecy and corruption grow substantially.

Peter Bosshard, former Policy Director and now Interim Executive Director of International Rivers, agrees that improvements to the system of evaluating and approving large infrastructure projects such as dams need to come from more effective legislation rather than voluntary codes of conduct: “I doubt whether it would be effective to ask dam builders to undertake separate ethical assessments of their EIAs, for two reasons: First, as the authors of the new study point out, many companies have already committed to the principles of sustainable development, but the concept is so vague that in practice it is difficult to pin them down to it. Like sustainable development, ethical behavior is a worthy but broad and general concept,” Bosshard told Mongabay. “I doubt that companies, which take liberties with their commitment to sustainability, would feel different about a commitment to ethics.”

“Secondly, ethical behavior should as much as possible be encouraged and mandated by laws and regulations, and not be left to the voluntary decisions of private companies. To use the example of EIAs, engineering firms which are hired by dam building companies to undertake such assessments always face a conflict of interest. If they strictly follow the science and act in the public interest, the dam building company may lose their dam contract and will not hire the engineering firms again. In such cases, the laws should be changed so that EIA firms are selected by the Environment Ministry — even if they are then paid [for] by the dam builder,” Bosshard said. “This would allow engineering firms to act ethically, without risking to lose out against their competitors.”

Rode and Le Menestrel recognize that while many companies continue to act unethically, focusing mostly on profit, others are taking steps to behave in a more positive socially responsible way. “Some companies really integrate sustainability and ethics in their identity and their strategy. Interface [the world’s largest manufacturer of modular carpet] is a great inspiration for many. Unilever [an Anglo-Dutch multinational consumer goods company] also explores many avenues in a proactive mode,” they said.

The researchers’ hope is that many more firms will follow suit. “With our work, we would hope to inspire companies to reflect on their decision making processes and on the ethics of their actions. In the end, everyone wants to contribute to the world and a meaningful life. Since we provide the example of a hydropower project it would be great if [our methodology] was picked up by companies working in that domain, but ultimately the framework is relevant for many — if not all — business sectors and countries.”

Eletrobras did not respond to a request for comment.

– This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.