The São Luiz do Tapajós mega-dam has been suspended by Brazilian authorities in a surprise turnaround that recognizes the presence of indigenous territories in the dam’s vicinity.

The São Luiz do Tapajós mega-dam, whose construction would lead to “social and environmental disaster” according to a Greenpeace report published last week, received a significant setback on Wednesday when its license was suspended by the licensing authority IBAMA (the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natura Resources).

The agency told Mongabay that the move is in response to a report published by FUNAI, Brazil’s National Indian Foundation, saying in an email that: “IBAMA has decided to suspend the environmental licensing process for [the] Tapajós dam complex, due to the information and recommendation from [FUNAI] that points to the infeasibility of the project from the perspective of an indigenous component.” In their report, FUNAI recommends the demarcation of 1,780 square kilometers (687 square miles) of indigenous Munduruku territory, known as Sawré Muybu, in the vicinity of the dam, according to International Rivers.

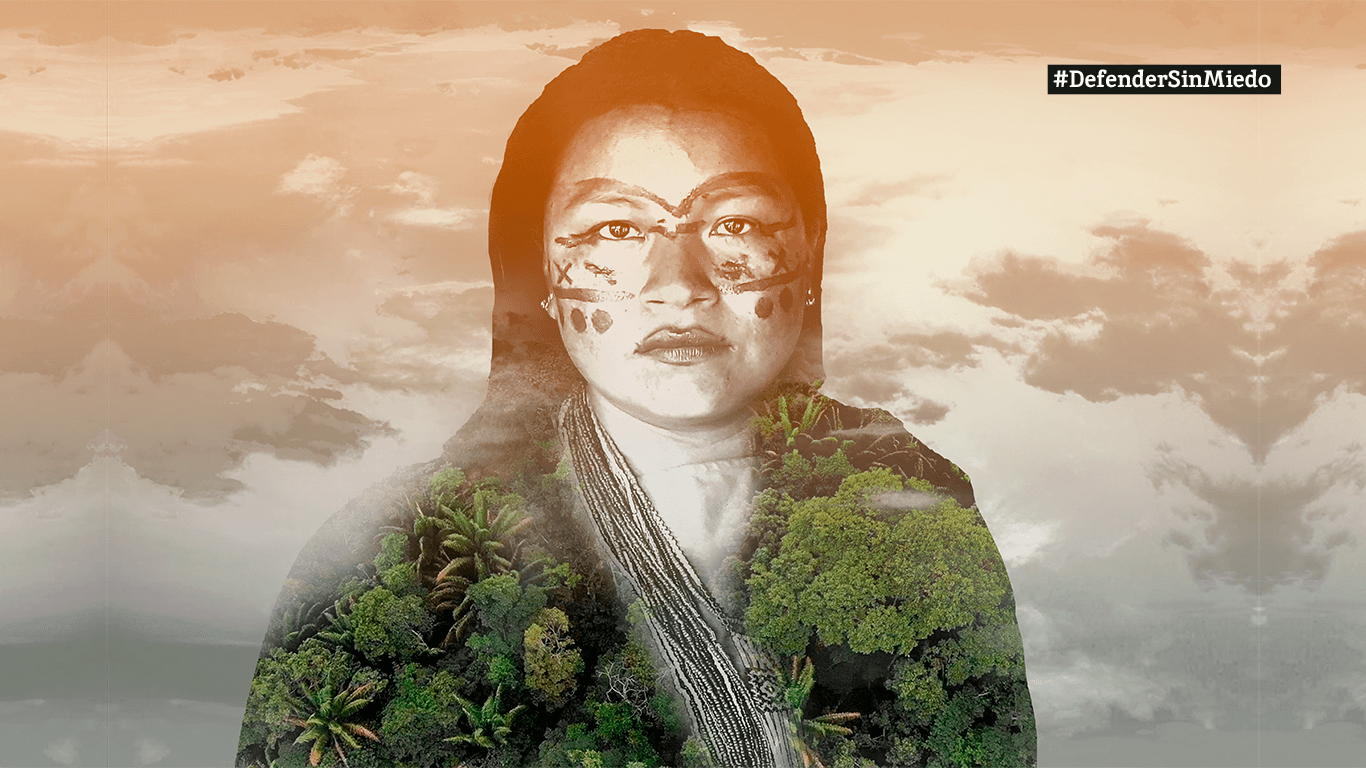

The Munduruku are vocal opponents of the dam’s construction: flooding would destroy the forest, fisheries and sacred sites that their livelihoods and culture depend upon. If demarcation goes ahead it would be a major barrier to the São Luiz do Tapajós project, because displacing indigenous people from their legally recognized lands is forbidden under Brazil’s constitution.

The suspension came as a surprise to environmental campaigners, with International Rivers describing the news as “a rapid about-face for the government, which has strongly pushed for the hydroelectric dam and repeatedly violated the Munduruku’s human rights.”

For the Munduruku, it marks a major success in their decades-long campaign for territorial demarcation of their land that stretches back to the 1970s. “This victory is the fruit of the union of our people, which has grown stronger and reached out to partners, who support our struggle and have made a great contribution,” Munduruki cacique Rozeninho Saw Munduruku, who lives in the affected area, was reported as saying by the Catholic Church’s Indigenous Council. “On this special day, which is the Day of the Indian, he [the president of Funai] didn’t sign it [the report] because he wanted to, but because of the pressure that we have been exerting for many years. This is the first step of our victory and we will continue in our struggle.”

Brent Millikan, Amazon Program Director at International Rivers, welcomed the news as “an important victory for the Munduruku people and their allies, and for democracy in Brazil. Demarcation is the first step in giving the Munduruku control over their ancestral lands and stopping this unnecessary project, which is riddled with corruption.”

While IBAMA’s decision has been heralded by indigenous groups and environmentalists, it is not the final word. The Brazilian government could overrule the decision — as happened with the contentious Belo Monte dam, which was built despite the agency’s objections. Uncertainty in the matter is magnified now because the Brazilian government is in chaos, with ruling Workers’ Party President Dilma Rousseff threatened with impeachment, and a more conservative government waiting in the wings to take power.

The Tapajós Basin at risk

Described as Brazil’s “hydroelectric frontier” the Tapajós watershed, in the Southeast portion of the Amazon basin, is under threat from more than 40 medium to large dams slated for construction. The Tapajós River is one of the last free-flowing rivers in the Amazon, and the hydropower developments planned across the region would not only violate the rights of indigenous people, but would also lead to extensive deforestation, and put numerous rare and endangered species at risk, Greenpeace warns in their report.

The São Luiz do Tapajós is the largest of the planned dams, at 7.6 kilometers (4.7 miles) wide, with an installed capacity of 8,040 megawatts. Its construction would flood nearly 400 square kilometers (154 square miles) of forest, with deforestation extending to 2,200 square kilometers (849 square miles), the report says.

The São Luiz do Tapajós, and four other proposed dams making up a major complex on the Tapajós and Jamanxim rivers, would be a catastrophe for the rich biodiversity and thousands of people in the region.

The report says that one of the most worrying aspects of the environmental impacts of Amazonian dams is how little they are understood. But it is clear that thousands of aquatic and terrestrial species — many of which are endemic, endangered, or undescribed — would suffer obstructed migration routes, habitat loss and degradation due to the dam’s construction. Species such as turtles, caimans, giant river otters, and dolphins — which depend on the seasonally flooded forests — will be directly affected. On land, the forest is home to jaguars, monkeys, birds, and bats, which will all see habitat lost to deforestation.

Greenpeace asserts that the full impacts have been downplayed by a “deeply flawed” Environmental Impact Assessment; that the communities affected have not had the opportunity to give their free, prior and informed consent as is their Brazilian constitutional right; and that potential financial returns have been hugely over-stated.

The international NGO is calling on both the Brazilian government and the global corporations that typically participate in Amazonian hydropower projects to urgently reconsider their development agenda in the Tapajós watershed.

“Banks, insurers, suppliers and contractors that become involved in these projects face serious financial and reputational risks,” Greenpeace says in the report, and it urged well-known companies including General Electric, Siemens, Munich RE, EDF, ENGIE, and others that have already expressed interest in the dams, or that have a history of involvement with Amazon hydropower projects, to focus instead on “helping Brazil to develop a clean energy future.”

Touted as a source of clean renewable energy, Amazonian hydropower is far from green. A cascade of negative impacts follows dam construction: reservoirs submerge tropical soil and vegetation — organic matter that emits significant greenhouse gases as it decomposes. Dams power the extraction industry, whose mines bring more infrastructure development. And the industrial waterways made possible by the Tapajós dams would promote large-scale agribusiness and commerce, which would drive further deforestation.

Dams not only contribute to both deforestation and climate change, but will also suffer the consequences of these destabilizing forces. As droughts become more frequent and rainfall decreases due to climate change and large-scale Amazonian deforestation, river flow will likely decrease significantly and become more variable. With dams unlikely to reach their installed capacity or provide reliable power generation as a result, the economic case for investment in hydropower is significantly weakened.

Greenpeace argues instead that solar, wind, and biomass generation, alongside efficiency improvements across the grid, could meet Brazil’s energy needs quickly and ethically. Given the likelihood of cost overruns in dam construction — as seen in developments such as the highly controversial Belo Monte dam — they argue that this would also be an economical choice.

“In discussing Amazonian dams it is common to hear, after listing a long litany of devastating impacts, that Brazil needs the dam for its development and so must go ahead with the project anyway,” Philip Fearnside, a professor at the National Institute for Research in Amazonia (INPA), Brazil, told Mongabay. “This is definitely not the case for these dams, as Brazil is one of the world’s most fortunate countries in having opportunities for other choices,” including energy efficiency measures and “tapping Brazil’s vast potential for wind and solar power.”

“Unfortunately, these other options do not offer the same opportunities for obtaining political campaign contributions from construction firms (as well as other less-public payments), as so dramatically revealed by Brazilian courts in recent weeks,” Fearnside continued, referring to the ongoing Lava Jato corruption scandal engulfing many political and business figures in Brazil.

“This is the moment to change these perverse aspects of the ‘landscape’ of Amazonian development,” Fearnside concluded.

Christian Poirier, Program Director at Amazon Watch, welcomed the report, telling Mongabay that it “should spur the Brazilian government and international dam profiteers to take notice and stop their destruction of the Amazon’s irreplaceable ecosystems and communities.”

The Brazilian Ministry of Mines and Energy, in a statement to Mongabay, maintained that “The current Brazilian hydroelectric projects are characterized by the respect for the environment and the population.” They asserted that existing conservation areas and recognized indigenous lands would ensure that “indigenous rights, the environmental conservation and the usage of hydraulic potential may have a harmonic coexistence.”

The ministry also said — just the day before FUNAI published their report in favour of demarcation of the Munduruku territory — that “It is important to understand that there is no approved or demarcated indigenous land nearby the Project implementation area,” and that the government is “permanently open to dialogue” with communities. “[I]ndigenous people are heard throughout the licensing process stage,” they stated.

But Greenpeace asserts that in addition to a lack of appropriate consultation, the federal government has until now deliberately obstructed the Munduruku people’s efforts to have their Sawré Muybu territory, which stands in the way of the São Luiz do Tapajós, demarcated. A governmental “security suspension” — intended for use only when national security is at risk — resulted in a judicial decision that put the dispute on hold, a move that Greenpeace describes as the Brazilian government “actively misusing the legal system to flout its own legal obligations.” The move now by FUNAI to recommend demarcation and recognize Munduruku claims — if upheld — could be a game changer.

“The root of the problem is both Brazil’s development-at-all-costs strategy and companies’ willingness to abandon basic environmental and human rights standards,” Daniel Brindis, senior forest campaigner at Greenpeace USA, told Mongabay.

Potential multinational corporate involvement

When approached by Mongabay, Munich RE, Siemens and General Electric neither confirmed nor denied their potential involvement in the Tapajós developments.

“A decision in favor or against participation is made on the basis of all available information, weighing carefully all relevant aspects, including ESG [environmental, social, and governance] criteria,” Munich RE told Mongabay. “We therefore do believe that our underwriting practice is not incompatible with our corporate responsibility statement.”

General Electric acknowledged the controversy surrounding Amazonian hydropower, saying “We understand and respect that there are many different perspectives on these types of projects and we take those into consideration in our evaluation as is standard practice in the industry.”

Both General Electric and Munich RE also emphasized their commitment to renewable energy.

Siemens told Mongabay that their potential involvement “depends on the outcome of an analysis of the legal and environmental aspects by the Brazilian authorities,” and that “Siemens always acts in line with national and international laws and regulations and supports initiatives that can contribute to reducing the environmental and social impacts of projects such as this one.”

Reliance on the Brazilian legislative process, and compliance with national law, is not good enough, Greenpeace says, when key parts of that process — such as adequate environmental impact assessments; and free, prior and informed consent for affected communities — are absent.

“São Luiz do Tapajós violates international norms on indigenous rights,” Brindis said. “The companies that have sustainability and human rights commitments that go beyond the Brazilian legal standards should apply such policies and disqualify projects like São Luiz do Tapajós on [that] basis.”

“Any company making its decision to participate in São Luiz do Tapajós based simply on whether or not the Brazilian government is calling the project ‘legal’ is wilfully ignoring what is happening in Brazil today,” he added.

Brindis pointed out that from a corporate perspective, “it is easy to ignore the reality when these projects have such big development myths behind them and take place so far away, where the people impacted are not heard.”

“I would never imagine Siemens involving itself in such destruction in Bavaria or GE taking part in such devastation and human rights violations in New England,” he said.

An uncertain future for the Tapajós

Greenpeace views intense public pressure as being crucial to forcing a shift away from Amazon mega-dam infrastructure projects like those in the Tapajós Basin. Poirier is hopeful that the time for that shift has come. “The disaster of Belo Monte is a clarion call to a growing coalition of grassroots and global movements whose collective struggle will put an end to these abuses, drawing a line at the Tapajós River, while forging sustainable alternative development models,” he said. The Belo Monte mega-dam has become notorious for a litany of environmental and human rights violations, amid allegations of massive corruption.

Brindis agrees. “We are talking about an industry that is enabled by global business partnerships, so the public needs to raise its concerns to the decision makers at these multinational companies wherever they are,” he said. “There is a reason why these companies give human rights and sustainability a lot of lip service. They know people do care.”

Although IBAMA’s license suspension is a critical first step in stopping the dam’s construction, the project’s cancelation is far from assured. Similar numerous suspensions dogged but did not derail the Belo Monte dam’s construction. The previous use of security suspensions to settle disputes, and the fact that the government has stated on the record that “The building of the Tapajós dam is non-negotiable” means that a positive social and environmental outcome is far from assured.

“This move gives the Munduruku and other local peoples some breathing room, but it is premature to declare the project dead,” cautioned Brindis. “It is possible for the current government (or a next administration) to re-open the licensing process.”

Brindis sees decisive corporate action as vital in light of the suspension: “companies who reportedly were vying to be a part of the project — including Siemens, Andritz and General Electric — must act now and publicly withdraw any support for São Luiz do Tapajos.”

“Given the political volatility of Brazil today, no one can really predict what will happen next,” Brindis added. But with continued pressure from the Munduruku and their allies, there is reason to be cautiously optimistic that a shift in approach to Amazonian hydropower development may be on its way.

“We know that there will be a [government and corporate] backlash, and we know of other projects that will have an impact on our lives and our culture, like the hydroelectric dam that they want to build on the Tapajós,” Rozeninho Saw Munduruku was reported as saying. “We are fighting for our territory and to help humanity. We want people to join us in our struggle as we are fighting for a better future for all of us.”

EDF, ENGIE, Eletrobras and ANDRITZ did not respond to requests for comment.

– This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.