Peru may be worried to conservation of its tropical forests, but deforestation has been increasing, much of it due to expanded cultivation of African palm oil.

Peru may be playing a more visible role in climate negotiations, especially related to conservation of its tropical forests. But despite this, deforestation has been increasing over the past 15 years, especially in its Amazon region. Much of the increase is related to expanded cultivation of cash crops such as coffee, cacao, and African palm oil, according to the Environment Ministry.

“Since 2000, agroindustrial crops have become the driver of deforestation,” says William Llactayo, a specialist in the Environment Ministry’s Land-Use Planning Office. New satellite maps showing “hot spots” of deforestation around large-scale plantations also shed light on how those operations encourage the clearing of land for agriculture, either by contracting with nearby farmers or by attracting land speculators. The images, analyzed by the Amazon Conservation Association’s Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project, show small-scale deforestation —apparently for smallholder agriculture— expanding near existing palm plantations.

Current regulations do not establish clear definitions for small, medium, and large-scale plantations, according to Litz Tello Flores, a legal specialist in the Environment Ministry’s Land-Use Planning Office.

In Ucayali, the images show a scattering of deforestation, especially in 2013 and 2014, between two plantations owned by a group headed by Czech businessman Dennis Melka. Both total about 9,000 hectares, according to Amazon Conservation Association data. And while the satellite images do not show that the plantations expanded in 2014, they reveal a spurt of clearcutting along the edges of the farms.

Although company spokespersons and local government officials have said the area consists of forest degraded by logging or farming, analysts for the Amazon Conservation Association maintain that the area being cleared consists of mature, closed-canopy forest, even where the growth is secondary.

The clearcutting trend continues, according to Iván Flores, who has witnessed it first hand.

Flores once had a “certificate of possession” to several hundred hectares of forest at the corner of what is now a huge expanse of young palm trees owned by Palmas de Pucallpa SAC, one of the companies associated with Melka.

Because Peruvian law does not permit private ownership of public forest, smallholders cannot obtain land titles that would give them formal ownership. Flores and his family had a rustic house on the bank of the Aguaytía River, at the edge of the woods, where he hunted and had a small nursery of trees for forest restoration.

But the last time he went to the Ucayali regional government’s agriculture office to renew the certificate of possession, he said, his request was denied. And now, forest and swaths where his neighbors had lived are being parceled off or granted to others in a scheme that they say amounts to land speculation.

Flores and several neighbors have joined forces with the indigenous community of Santa Clara de Uchunya, on the other side of the Aguaytía River, in a last-ditch effort to save their forest.

On January 12, the regional agriculture office informed Joel Nunta, the president of Santa Clara de Uchunya, that it had granted certificates of possession to 17 people in an area claimed by the community as part of its ancestral territory.

Those certificates could be the first step toward turning that area into private property. Poor enforcement or corruption could enable smallholders or speculators to clear part of the land, to claim they have been farming it, and apply for title. Once titled, the land could be worked as a farm or sold to the plantation.

The conflict between Santa Clara de Uchunya and the palm plantation reflects a drama that is playing out across the Peruvian Amazon.

With a title to only 200 hectares of land, Santa Clara’s population is outgrowing its territory and claiming a swath of forest across the river where the ancestors of the current Shipibo and Cacataibo residents hunted and fished, and where some community members still have small plots of crops.

Nunta and other community leaders say the government has allowed deforestation for the plantation and small farms around it, despite Santa Clara’s official petition for an expansion of their territory. Their claim joins those of other indigenous groups that are still seeking titles to their community lands, or who have petitioned for expansion. Some groups seek to reclaim ancestral territory that now falls in protected areas.

The Ese’eja in the southeastern Madre de Dios region are claiming part of the Tambopata National Reserve, and a Kukama Kukamiria organization is seeking to recover part of the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve in the northeastern Loreto department.

Wampis organizations in northern Peru recently announced that they were establishing a Wampis nation, and Awajún federations are seeking to do the same.

Peruvian indigenous organizations say the government has been dragging its feet on requests for formal titling of more than 1,000 indigenous communities, totaling some 20 million hectares of land.

But while Santa Clara de Uchunya pursues its case before the government –and possibly the courts– the community is being overtaken by events.

The Amazon Conservation Association’s satellite image around the plantations reflects the deforestation that is occurring as people move in and clear land in an effort to obtain titles. Some may hope to later sell their land to the plantation, but others are smallholders gearing up to plant oil palm under an “outgrower” system. Outgrowers are independent palm producers who sell their palm to a nearby plantation, often in exchange for credit or technical assistance, especially for planting and during the first few years, before the trees begin to produce.

The expansion of palm, along with coffee and cacao, has driven deforestation especially in San Martín, which bills itself as Peru’s “green” region, but which has the country’s highest deforestation rate. San Martín lost an average of 24,300 hectares a year between 2010 and 2014, for a total of 97,200 hectares, according to an Environment Ministry report.

It was closely followed by the huge northeastern region of Loreto, with 97,857 hectares deforested, and Ucayali, home to two large palm plantations and a number of smaller ones, as well as cattle ranches and coca crops, with 80,349 hectares deforested.

Huánuco, which also shows up as a hot spot for recent deforestation, ranked fourth for accumulated deforestation between 2010 and 2014, with 56,720 hectares.

Altogether, the amount of forested land cleared in Peru in between 2010 and 2014 was larger than the U.S. state of Rhode Island, according to the Environment Ministry report.

The highest deforestation rates are in “unclassified” state-owned forest –wooded areas that have not been categorized as protected areas, productive forest, timber concessions or protective cover.

Many of the people who are clearing Amazonian forests and seeking titles are migrants from other parts of Peru, especially the highlands and the cost, according to legal specialist Tello.

“They go with the mentality of getting the greatest possible profit,” which often leads to land speculation, she said.

Peru has set a goal of “net zero” deforestation by 2021 and has received pledges of some $300 million from Norway and German to shore up its forest management.

But overall deforestation has been creeping upward. Except for a drop in 2013, deforestation has been increasing steadily since 2006, according to calculations by Terra-i, reproduced in the Ministry of the Environment’s report.

Recent regulatory changes are aimed at controlling the reclassification of forested land for agricultural use, according to Katherine Riquero, who heads the Agriculture Ministry’s Office of Agricultural Environmental Affairs.

In Peru, land use is governed by whether the soil is classified as suitable for agriculture or suitable for forest. Even land with mature forest cover can be classified as suitable for agriculture, depending on the soil chemistry.

Peru’s government decentralization in recent years had given regional governments more power to approve land-use change and deforestation, but the forestry law passed in 2013 and its enabling legislation, approved in 2015, have given Riquero’s office and the National Forest Service (SERFOR) the leading role.

Riquero’s office now receives requests for classification of soil as suitable for agriculture. Even smallholders are supposed to begin with that step, although Tello says they often begin clearing land without permission, taking advantage of weak enforcement in rural areas.

According to the regulations, anyone seeking to use unclassified land for agriculture must have a laboratory analyze soil samples and send the results to Riquero’s office, which decides whether the primary land use should be forest or agriculture. The landholder must also submit an environmental impact study, which is evaluated by Riquero’s office, as well as the Environment Ministry, the National Water Authority and the National Forest Service. The Environment Ministry now issues a binding opinion, which means it can block requests for land-use change.

The Forest Service must approve the clearing of forest for agriculture, although regional governments issue the actual permits for clear-cutting. At least 30 percent of the forest must be left standing.

The procedural changes, particularly the binding opinion from the Environment Ministry and the role of Peru’s relatively new Forest Service, are designed to reduce deforestation for agriculture, Riquero said.

In practice, however, people continue to sidestep the regulations because of a lack of enforcement, she said. Her four-member inspection team cannot keep up with the workload.

Riquero and other government officials insist that palm oil should be restricted to land that has already been degraded —such as abandoned pasture or fields.

“The goal is for agriculture to be sustainable,” she says.

But agroindustrial companies seek large swaths of land to obtain economies of scale. Riquero says there are about 10 million hectares of degraded land suitable for agriculture in the Peruvian Amazon, but they are scattered, not in areas large enough for a large-scale plantation.

Small-scale palm growers are more likely to plant palm in fields or pastures, but when they expand, this may come at the expense of forested land.

If land speculation in the area between the two plantations in Ucayali results in many smallholders gaining title to plots of 40 or 50 hectares in that area, Riquero worries that the Melka group could eventually buy that land from smallholders and turn the area into one huge plantation.

One solution, according to Riquero, would be to map soil types in the entire Peruvian Amazon to determine where agriculture would be permitted. She estimates that a study of the region’s 40 million hectares would take about six months and would cost $40 million.

Such a map would allow comprehensive planning and enable regional governments to better organize land use, she says.

Meanwhile, Iván Flores and his family watch chain saws chipping away at the forest they once planned to protect. Not only have other people laid claim to the forest, they say, but someone has set up markers, apparently planning to subdivide the area for sale.

They still hope Santa Clara can gain rights to the land before the forest is gone.

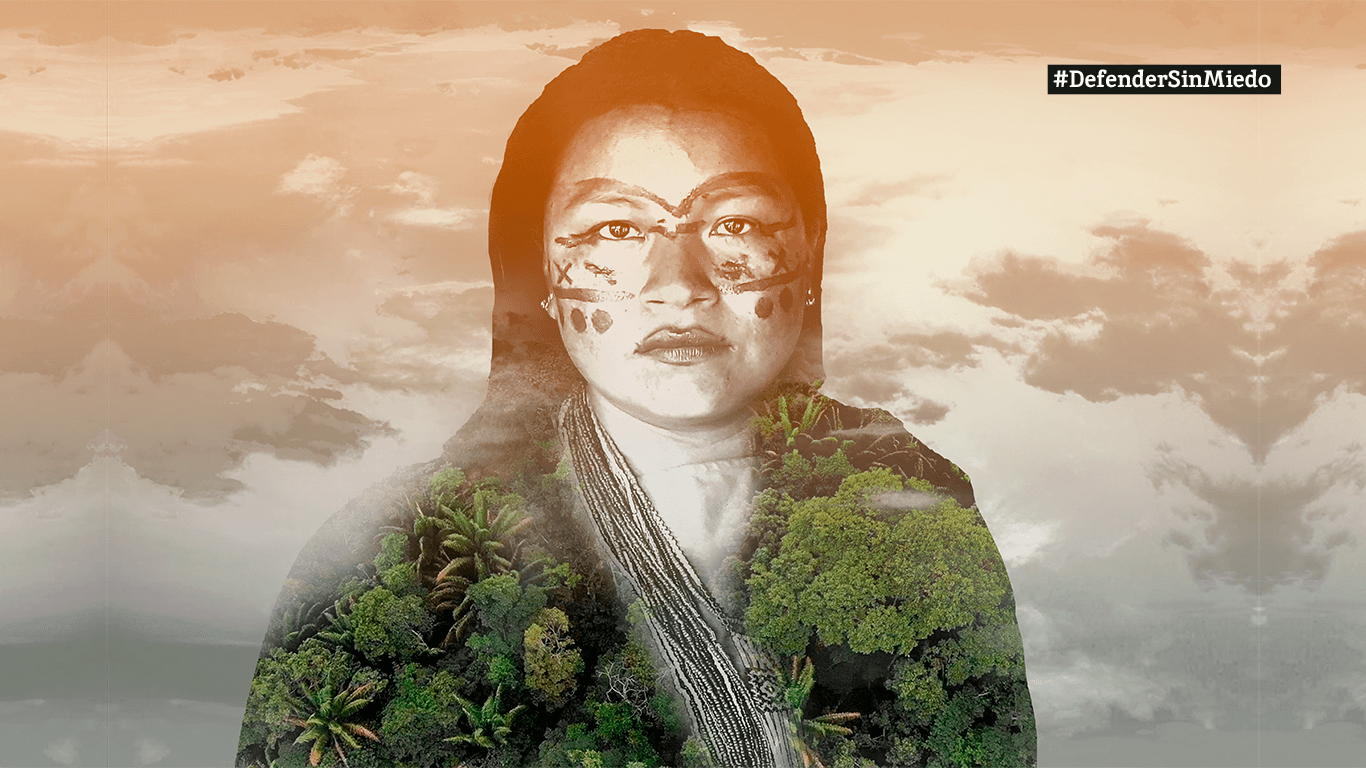

Ivan Flores, whose family’s land sits adjacent to the Plantaciones de Pucallpa plantation, said he’s seen more flooding since the nearby forest was cleared for oil palm. Photo by John Cannon.

– This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.