New study asserts lax, nonexistent land rights put indigenous-held forests at risk of development

Carbon emissions from human activities are the big player in global warming, and scientists have long known that tropical forests are vital for sequestering excess carbon. A new study released today in Carbon Management finds the total carbon load locked up in parts of the Amazon rainforest held by indigenous groups to be much higher than previously estimated – an amount that, if released, would be capable of destabilizing the earth’s atmosphere. But because of flimsy land rights, these areas stand at risk of deforestation.

Tropical forests are vital for sopping up and storing excess atmospheric carbon that is warming the globe at an unprecedented rate, as well as acidifying seawater. A 2009 study published in Nature found that rainforests absorb nearly 20 percent of carbon emissions every year.

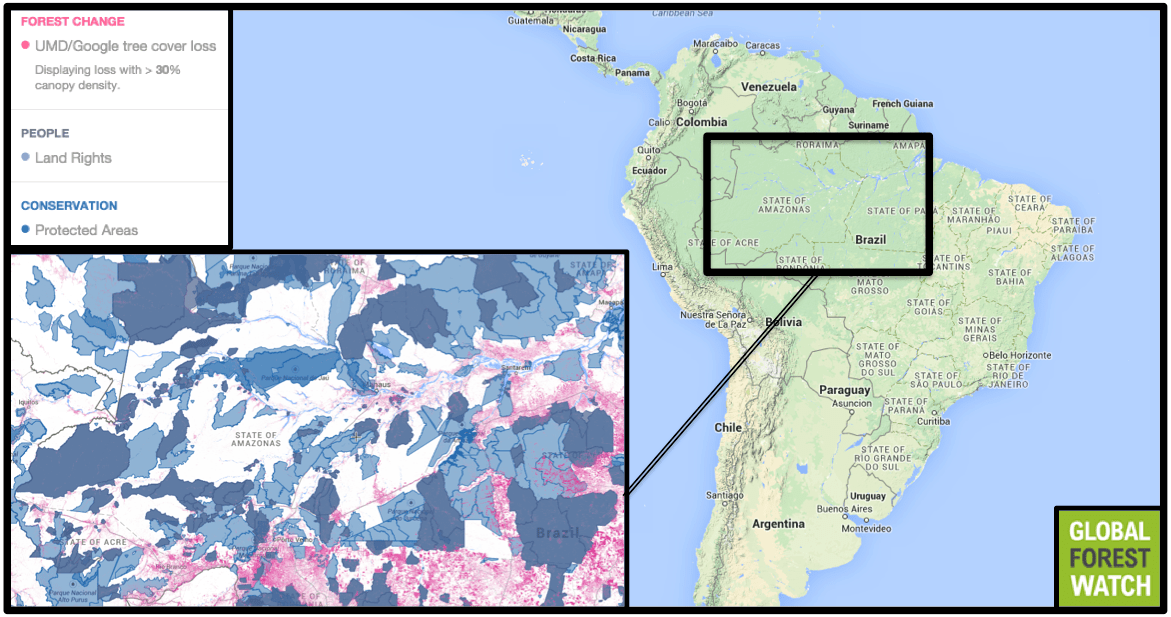

But this important ecosystem service is not possible without the presence of trees – lots of trees. And as forests around the world are cleared and changed by human activities, not only is more carbon released into the atmosphere, but less can be taken out. According to data from Global Forest Watch, the Amazon Basin lost approximately 12 million hectares of tree cover from 2001 through 2012 – and area of land about half the size of the UK. In addition, droughts are heavily affecting parts of the Amazon, killing trees, changing forest composition, and reducing carbon storage capacity. Making the problem worse, some important rainforest tree species may be detrimentally affected by heightened atmospheric CO2 levels.

The carbon load of the Amazon rainforest spans nine countries, and about 52 percent of it is contained in indigenous territories – an amount that exceeds the carbon loads of the tropical forests of Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo combined, according to the authors.

Logging, both legal and illegal, as well as the building of dams and the clearing of land for agriculture, mining, and fossil fuel extraction threaten 20 percent of the Amazon’s carbon-rich forests, according to the authors of the study. Inadequate land rights are allowing developers to exploit indigenous territories; in some places, indigenous communities have no officially recognized rights to their land at all. The study recommends establishing and strengthening indigenous rights should be at the forefront of forest protection policy.

“The solution is to recognize the rights of indigenous peoples to territories that have not yet been officially recognized, and resolve territorial conflicts that pit protected areas against private interests,” said Alessandro Baccini, also a researcher with the Woods Hole Research Center.

A large portion of the Amazon is being considered for development, with potentially disastrous consequences if realized. Even protected areas would not be immune, with an estimated 30 percent standing to be affected.

“If all the current plans for economic development in the Amazon were actually implemented, the region would become a giant savanna, with islands of forest,” said Beto Ricardo, of the Instituto Socioambiental of Brazil.

The authors write that maintaining the stability of the atmosphere hinges on whether or not the nine Amazonian countries adopt policies that ensure the ecological health of indigenous territories and protected areas.

“We have never been under so much pressure, and this study demonstrates that” said Edwin Vásquez, president of COICA, the Indigenous Coordinating Body of the Amazon Basin, which represents the indigenous groups in the region. “Yet we now have evidence that where there are strong rights, there are standing forests. It is clear that to strengthen the role and the rights of indigenous forest peoples, is to prevent climate change.”

The study was released during the Lima Climate Change Conference, which began yesterday in Lima, Peru. The U.N. event addresses climate change and aims to establish a framework for action to stabilize greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and curb global warming.

This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.