Residents who live along the highway support its repavement in the hope of improving access to medical care, but scientists are expanding research that warns of an increase in the spread of infectious diseases due to deforestation stemming from the road.

In Igapó-Açu, a community in the interior of the Amazonas state, 75 families live beside the unpaved BR-319 highway running through one of the most biodiverse regions of the Amazon Rainforest. There, they are a two-hour drive from the nearest doctor, but just a few steps from the road, which, if repaved, could trigger a series of infectious diseases due to deforestation.

InfoAmazonia visited the region in December last year with researchers and health professionals from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) and the State University of Campinas (Unicamp). The trip was part of a long-term project in which the two institutions investigate the presence of infectious diseases and offer medical care along the BR-319, which connects Manaus, capital of Amazonas, to Porto Velho, capital of Rondônia.

The decades-long debate over whether to restore and repave the BR-319 largely focuses on the project’s economic and environmental consequences. But over the course of five days in Igapó-Açu, InfoAmazonia documented how this conflict between development and preservation also has profound impacts on the public health of the population that borders the highway.

For communities along the BR-319, where basic sanitation is inadequate, access to drinking water is limited and hospitals are kilometers of precarious road away, repaving the highway could improve access to public health services. However, Indigenous peoples in the surrounding area say that the road has caused deforestation and pollution near their territories, leading to health problems in their communities.

Paving the highway could also cause an increase in infectious diseases and even new pandemics, according to a study released in February last year led by the biologist from the Federal University of Amazonas (Ufam) and the University of São Paulo (USP), Lucas Ferrante. It would allow for increased settlement and development in one of the most preserved sections of the Amazon, which is home to countless pathogens. Researchers say the resulting environmental degradation could improve microorganisms’ ability to multiply between species and cause the population of mosquitoes and other pathogen vectors to grow. It would also bring people into contact with unknown diseases.

“Our monitoring indicates the presence of pathogens with high transmission capacity in this area. The region is home to a diversity of viruses, fungi and bacteria that are still unknown, many of which have a high infectious potential,” said Ferrante, adding that his research has shown “an increase in the transmission of contact pathogens, driven by the greater mobility provided by the highway.”

Our monitoring indicates the presence of pathogens with high transmission capacity in this area. The region is home to a diversity of viruses, fungi and bacteria that are still unknown, many of which have a high infectious potential.

Lucas Ferrante, biologist from the Federal University of Amazonas (Ufam) and the University of São Paulo (USP)

Joel Henrique Ellwanger, a professor of genetics at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul who studies how environmental disruption in the Amazon influences infectious diseases, agrees with Ferrante. “Highways in the Amazon are known vectors of deforestation and loss of biodiversity,” he said. Ellwanger added that environmental degradation “contributes to new pathogens reaching human populations, with the risk of new pandemics emerging, leading to astronomical economic losses and costs in terms of human lives.”

Several Brazilian presidents have declared their intention to pave the BR-319. However, for now, the only paved sections are those at the ends of the highway, close to Manaus and Porto Velho. A preliminary license for paving the highway was issued in 2022 under the administration of former president Jair Bolsonaro. The license was later struck down in court, but was reinstated in October 2024 by an appellate judge. Even so, the fate of the highway is far from being decided.

A community living off the highway

Opened in 1976, the BR-319 was a key component of the Brazilian military dictatorship’s plan to colonize the Amazon. Initially, the highway was built with asphalt, which encouraged the arrival of people from outside the region. But a decade after opening, the road fell into disrepair. Almost 40 years later, in 2015, it began to be maintained and traversed again–but this time as a dirt road.

The section in the worst condition, known as the “passage of the middle,” is approximately 400 kilometers long and becomes almost impassable during the Amazon’s rainy season.

The lives of the residents of Igapó-Açu are inseparable from the debate over the BR-319. There, the houses built of wooden planks and stilts all face the road. Some serve as rest stops for hungry and tired truck drivers passing through, while most of the jobs in the community come from a sluggish ferry that transports cars across the town’s narrow river.

One of the community’s leaders, Nilda Castro dos Santos, known as Dona Mocinha, has lived in Igapó-Açu since 1980. She said that in the highway’s heyday, the town had 100 families. But after the road was closed in 1988, her family was one of just five who remained. “It was very painful,” she said. “It was 20 years of suffering.”

João Joventino Cordeiro, who arrived in a community near Igapó-Açu even before Dona Mocinha, experienced similar desolation when the road closed. “30 years passed without a car passing by,” he said, adding that getting to a doctor was practically impossible: “Only God took care of us.”

After the highway reopened in 2015, people returned to communities like Igapó-Açu. Currently the region receives a consistent flow of truck drivers, travelers and groups of adventurous motorcyclists. But the reality is that the town is still much less busy than when the highway had pavement, residents say.

In communities along the highway, there are few jobs, economic activity is scarce and most services are hundreds of kilometers away, such as in Manaus, around 270 kilometers up the road. In Igapó-Açu, the nearest hospital is in the city of Careiro Castanho, 150 km away by unpaved road.

A resident of the region for almost 50 years, Antônio do Boto, known as “Seu Botinho”, summed up the situation when someone in the community gets sick: “There is no ambulance to take you. You could lose your life because you don’t have transportation.”

There is no ambulance to take you. You could lose your life because you don’t have transportation.

Antônio do Boto, a resident of the region for almost 50 years

Although he believes in improving local access to medical care, Seu Botinho, who works on a project to restore the turtle populations in the region, also expressed concern about the environmental impacts related to deforestation if the highway restoration project takes place.

“The game, animals, birds that live inside the forest begin to move away. And then you no longer see a bird, you no longer see an animal,” he said.

Medical assistance is one of the many things that the people of Igapó-Açu hope will become more accessible if the highway is paved. For them, the restoration of the road would reduce travel time, while the increased frequency of transport such as buses could provide a more reliable trip to the hospital in Careiro.

But the scientist Ferrante believes that a better solution to the problems of residents’ lack of access to medical care would be to redirect the billions of reais needed to pave the highway to medical services for those who live in the region.

“If we took the resources for pavement and allocated them to health and education in the municipalities, we would solve the municipalities’ problem,” he said.

If we took the resources for pavement and allocated them to health and education in the municipalities, we would solve the municipalities’ problem.

Lucas Ferrante

Impact on indigenous lands

The impact of the repavement of the BR-319 could reach 68 indigenous lands, according to a study carried out by Ferrante in 2020. Furthermore, an exclusive analysis by InfoAmazonia revealed that the opening of extensions along the highway would affect 38 conservation units. One of these territories is that of the Mura people, in the municipality of Manicoré.

Less than 40 kilometers from the highway, the Indigenous group has suffered more cases of diarrhea and respiratory illnesses, says Adamor Leite, one of the Mura’s leaders.

Leite said that the problems have been caused by farmers and hunters entering the region via the highway. These people, he said, pollute rivers, destroy the community’s sources of food and medicine and contribute to the spread of disease-causing organisms.

“The problem of respiratory infections, flu and illness has increased,” said Leite, adding that deforestation destroys “the medicinal plants that are used to treat some diseases.”

The Indigenous leader also believes that with the paving of the highway, the territory runs the risk of suffering invasions with the opening of additional ramais, which are paths opened often illegally from a main road — in this case, the BR-319.

“If [the road] is paved, [deforestation] increases and this could cause worse damage,” said the Indigenous leader.

The Juma Indigenous people also report concern about the presence of outsiders close to the territory, which would worsen in a possible reconstruction of the BR-319. Their territory is in the municipality of Lábrea, in the Açuã River region, in the south of Amazonas, close to the highway.

“We’ve seen that non-Indigenous people are coming to hunt within our territory, taking away our sources of food,” said Kunhave Juma, president of the Juma People’s Association, adding that the outsiders have also spread illnesses and led to additional health problems in the community.

Researchers estimate that the federal government does not have the money or structure to effectively monitor and protect the area around the highway, including Indigenous territories.

Deforestation and the climate crisis

A study by the Federal University of Minas Gerais, published in 2020, pointed out that paving the BR-319 could quadruple deforestation rates and carbon emissions in the surrounding area, which would largely prevent Brazil from achieving the carbon emissions reduction targets it committed to in the Paris Agreement.

That environmental destruction could also have a significant impact on the climate of the Amazon, causing heat waves in Manaus that would make the city almost uninhabitable, according to Ferrante.

To give an idea of the impact that paving the highway could cause, even just government promises to repave sections of the highway have already led to an increase in deforestation. Between 2020, when Bolsonaro said that paving the BR-319 would be a priority, and 2022, deforestation around the highway increased 122%, according to the Climate Observatory. The road has 6,500 kilometers of illegal extension paths into the surrounding forest, six times the length of the original highway, according to Ferrante’s research.

But in addition to the collapse of biodiversity and increased carbon emissions, the historic environmental degradation emerging from the BR-319 could be accelerated by its repavement and cause transformative public health impacts for those living in the region.

‘The good and the bad’

During the December visit to Igapó-Açu, the public health implications of the debate over the BR-319 were apparent.

Among the residents cared for by the Fiocruz and Unicamp team, there was a young mother who was diagnosed with worrying blood sugar levels. Up the road, a man had lost three of his pigs to rabies (likely transferred by the many bats in the area) but was unable to get medical professionals to come vaccinate his wife or child for the disease – a reflection of the lack of medical care for those living on the BR-319.

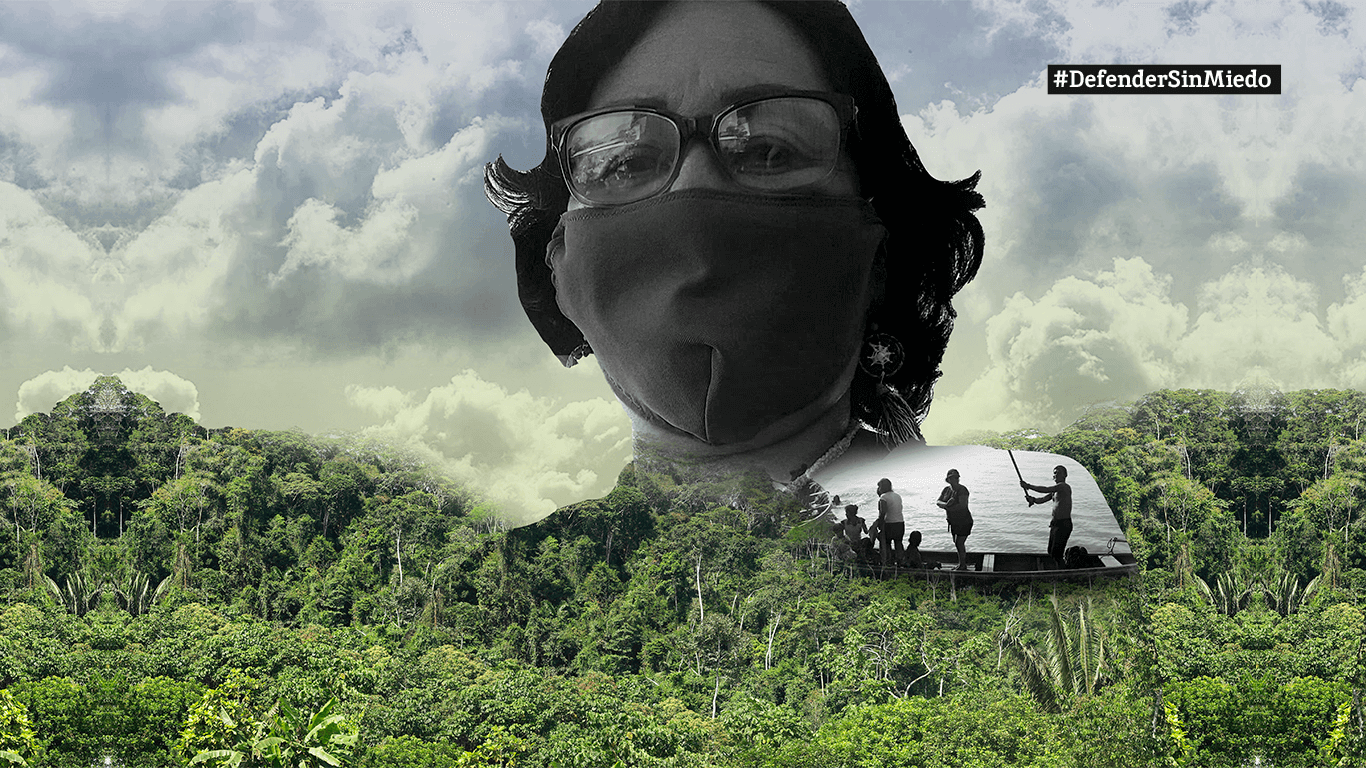

About a year ago, Dona Mocinha got sick with a mysterious illness. “I spent more than a week in bed with a fever, chills and a lot of body aching. And I didn’t know what to do,” she said.

When the Fiocruz researchers later visited, Dona Mocinha took a test and was diagnosed with Oropouche fever, a disease that has symptoms similar to dengue fever, transmitted mainly by a mosquito popularly known as maruim or meruim.

“They told me what I felt was a maruim bite that gave me that discomfort, that fever,” she recalled.

In 2024, researchers from Fiocruz identified a new strain of Oropouche that originated in the Amazon and had the highest incidence in AMACRO, a region known as the “deforestation frontier.” Igapó-Açu is part of the region.

Dona Mocinha, who supports paving the highway because of the economic benefits it would bring to the community, expressed concern about the negative impacts of the highway, be it increased environmental destruction, crime or disease.

“With the development of the road, everything comes. The good and the bad,” she said. “In the midst of the good, bad things also appear, even disease.”