Although they live 186 miles away from an area along the Tapajós River where illegal mining is concentrated, the 300,000 residents of Santarém, a major urban center in the Brazilian Amazon, are at high risk of mercury poisoning. The warning comes from a study recently published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

The researchers analyzed the blood of a sample of 462 local residents from Santarém between 2015 and 2019 and found that 75.6 percent of them had mercury concentrations above the safe limit of 10 μg/L (micrograms per liter) set by the World Health Organization. The average concentration detected was almost four times higher than the safe limit. Among the riverine population, the contamination levels surpassed 90 percent.

The study, titled Mercury Contamination: A Growing Threat to Riverine and Urban Communities in the Brazilian Amazon, was carried out by the Federal University of Western Pará (Ufopa) in partnership with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), one of the most prominent Latin America Health Research Institutions, and the environmental nonprofit World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF-Brazil).

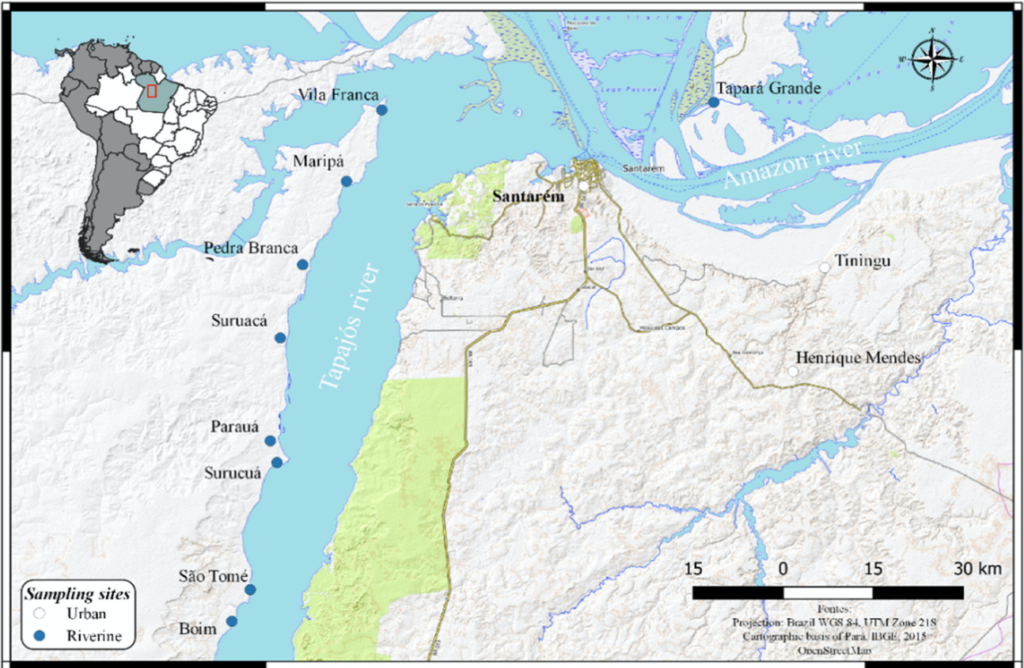

The researchers point out that the main source of contamination is the consumption of fish from the Tapajós River tainted by mercury. Of the study sample group participants, 203 live in Santarém’s urban area. The other 259 live in eight riverside communities, seven along the banks of the Tapajós and one on the Amazon.

Other studies had previously pointed to mercury contamination among populations living on the banks of the Tapajós, such as the Munduruku indigenous people, who in recent years have been fighting against the growing threat of clandestine mining in their territory. Now, the new data suggest that mercury contamination is widespread in the region. The researchers pointed out that the “exposure to mercury is not restricted to the areas near the gold mining sites, but can occur throughout much of the river basin, which is greatly impacted by gold mining.”

According to the authors, the “widespread, unregulated, and uncontrolled” use of mercury in mining activities has already released “thousands of tons of mercury-contaminated waste” in the Amazon biome. “In the Brazilian Amazon, mining was found to be responsible for environmental contamination, as well as wildlife and human exposure over the years,” they wrote, pointing out that “the magnitude of exposure remains unclear owing to the illegality of the sector, hampering credible data on the amount of mercury released in the environment”.

Participants who reported daily fish consumption presented higher levels of mercury in their blood. The researchers also noticed that other factors, such as the place of residence and schooling, increased the contamination risks. While the highest level of mercury was found among those without formal schooling (45.8 to 50.9 μg/L), the lowest was among those with college degrees (17.3 to 31.6 μg/L).

The contamination levels also varied according to age and gender. Male participants had higher mercury levels than women, and participants aged between the ages of 41 and 60 had a higher risk than the group between 21 and 40. Riverside dwellers who live on the banks of the Tapajós also had higher contamination levels (59.5 percent) than people who lived along the Amazon river (40.5 percent).

“Regardless of where the people live, exposure to mercury may occur, since it depends not only on eating habits but also on individual characteristics,” explains Heloisa do Nascimento Moura Menezes, a researcher at the Postgraduate Program in Health Sciences at Ufopa and the study coordinator. “Anyone who consumes fish frequently is at risk of exposure to mercury.”

The findings surprised local residents such as Larissa Neves, a nutrition student. “I knew the water was contaminated because whenever I bathe in the Tapajós I get itchy, but I wasn’t aware of the fish contamination,” she told InfoAmazonia. Despite the risks, she explained, it would be challenging for her family to cut down on fish consumption. “Every Sunday, baked fish is a time-honored tradition in my house because my father fishes and brings them home.” Her family also sells lunchboxes, and fish is invariably part of the menu. “At least twice a week we prepare fish for the lunchboxes. There’s no way I can stop eating it.”

Health risks

Mercury is a toxic heavy metal and can cause a series of health issues, including tissue damage and mental health deficiencies, as well as behavioral, immunological, hormonal, and reproductive changes. The study examined the effects of mercury exposure on liver and kidney functions. Participants with higher mercury levels presented the highest alteration levels in the indicators.

According to Moura Menezes, the scientific literature shows that, in general, people with higher levels of mercury contamination have more severe symptoms, but low levels of contamination are also noticeable. “That’s why it’s important to identify exposure to mercury early so that the symptoms don’t get worse,” she says.

Doctor Fábio Tozzi, Community Health Program Coordinator at the Health and Happiness Project in Santarém, more and more patients who work in mining or suffer directly from the consequences of the use of mercury in the activity are showing up with neurological, digestive, psychiatric, and respiratory symptoms. However, according to Tozzi, mercury contamination remains an underreported health issue “The diagnosis is still rare,” he says, “but due to the widespread mining in the region, this is starting to be a big concern.”

In response to the rising problem, Tozzi believes the health system should offer tests for mercury levels in primary health care exams. “Managers must be prepared to identify and mitigate the effects of mercury present in water and fish,” says the doctor, who also works in the development of primary care models for riverside populations, in a partnership between his non-profit organization with the city’s health secretary and Ufopa university.

Socioeconomic impacts

Since the study came out, fish sellers at Mercadão 2000, a traditional market in Santarém, have constantly assured customers that their fish are not contaminated. “This fish here is farmed, not from the river,” said seller Valdenir da Silva Lima to InfoAmazonia, while cleaning a Tambaqui. Another seller, who preferred not to identify himself, said that his fish come from the floodplain lakes of the Amazon River.

Customer Ninito José Miranda de Souza, who works as a private driver, had just bought a piece of Arapaima when he spoke to InfoAmazonia. “I eat fish all day long,” he said. After learning about the study, however, he said he would reduce fish consumption. “I’ll have to take a break. If it’s bad for my health, I can’t keep doing it.”

But other customers, such as Noêmia Pereira Duarte, a retired resident of the Santarem village of Alter do Chão, were suspicious of the study results. “All my life I’ve bought fish, it doesn’t have any mercury, that’s a lie,” she said, after buying Pacu and Acará fish.

Heloisa Moura Menendez, the study coordinator, explained that the study was not intended to have a negative impact on fishermen and traders. “We stand in solidarity with all those who directly or indirectly depend on fishing. I am not here to make a fuss, but rather to bring up a necessary and urgent discussion” she said.

We stand in solidarity with all those who directly or indirectly depend on fishing. I am not here to make a fuss, but rather to bring up a necessary and urgent discussion

Heloisa Moura Menendez, the study coordinator

According to Menezes, there are alternative ways to reduce exposure to mercury. “Our recommendation is not to restrict the consumption of fish. What we suggest is a change in eating habits, precisely because we are concerned with all those who depend on fishing to survive,” she explains.

According to the researcher, the population can start minimizing the risks by varying the type of fish consumed, since some fish, such as carnivores, have more mercury than others. Reducing the portions consumed and the frequency of consumption and introducing more fruits, vegetables, and antioxidant foods in the diet, are also recommended. “Knowledge is a precious tool when thinking about prevention,” she adds.

Menezes goes on to point out that the objective of the study is to promote a discussion about more sustainable practices to reduce mercury in the environment. “Reducing the level of mercury contamination in rivers and fish populations can take years, so what’s needed is not only to put an end to activities that release mercury into the environment but also to come up with ways to protect the health of the populations that live in the Amazon region and that will go on living together for many years with the consequences of the levels of mercury exposure that exist today,” she concludes.

Since the survey sampling phase was completed in 2019, illegal mining in the Tapajós River has mushroomed. According to a survey by the Instituto Socioambiental, between January 2019 and May 2021 alone, the area devastated by mining within the Munduruku Indigenous Land, located along the middle stretch of the Tapajós, grew by 363 percent.

This story was produced with support from Report for the World, a The GroundTruth Project initiative.