Chief Kaiaxi of Penedo village, whose areas are being traded on the internet as NFTs. Photo: Ramon Aquim/InfoAmazonia

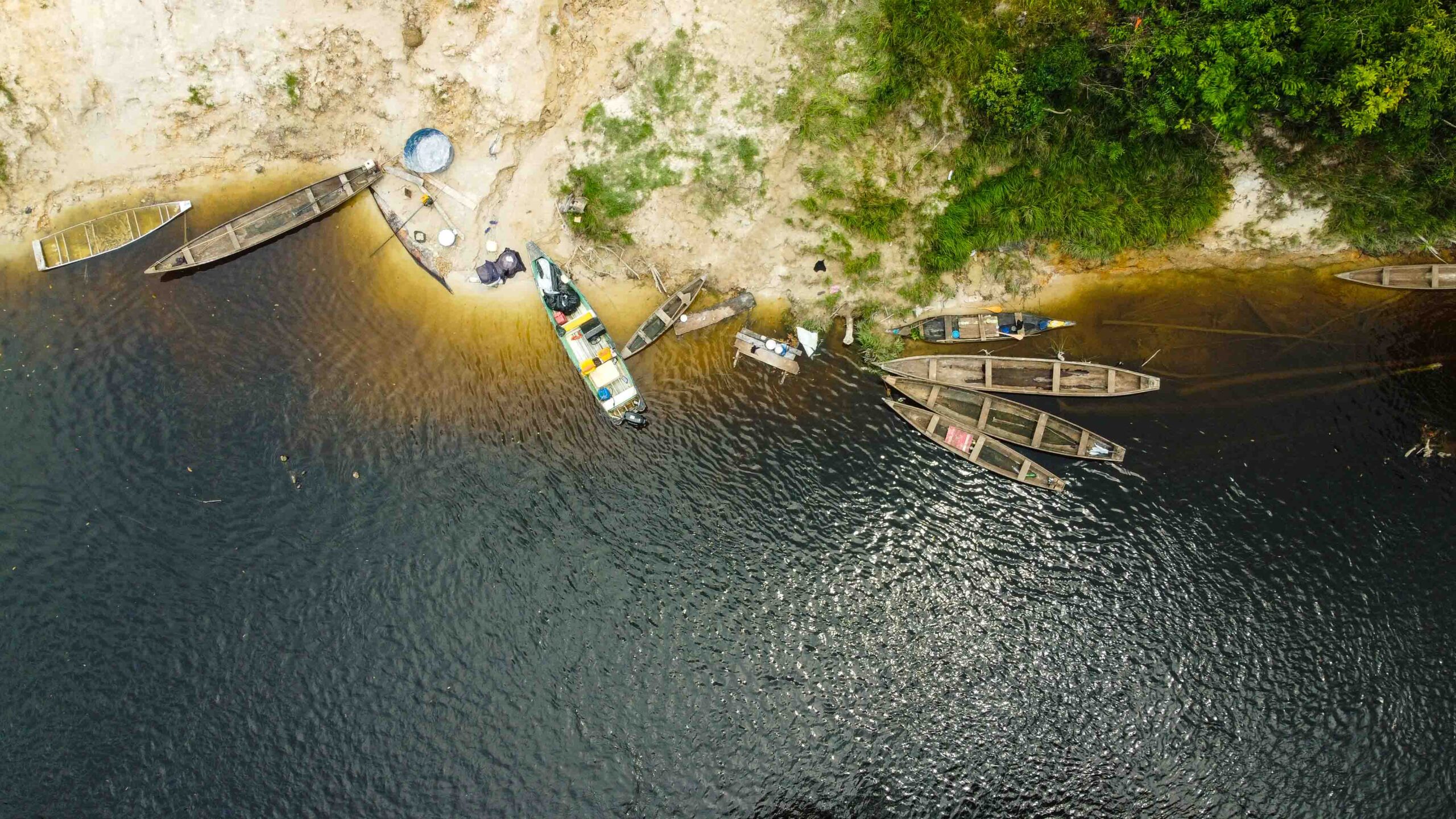

On their third day traveling on the Purus River Basin in southern Amazonas, InfoAmazonia reporters landed in the village of Penedo, on the banks of the Seruini Stream. For centuries, reports of persecution, massacres, torture, experiences of slavery and struggle for land have marked the history of the Apurinã Indigenous people, who took refuge in the forest, far away from their tormentors. Now, the threat is invisible: Their lands by the Seruini Stream are being sold on the internet as NFTs (non-fungible tokens) by Nemus.

The company said it acquired 41,000 hectares (101,313 acres) of an area that is part of the Lower Seruini/Lower Tumiã Indigenous land, whose demarcation process is underway. The area was divided into plots of different sizes, which have been sold on the internet since March 2022, with the promise of preserving the Amazon. Each NFT represents a portion of the territory, where Nemus still hopes to exploit 200,000 Brazil nut trees and generate carbon credits.

We were already getting off the boat when Chief Kaiaxi made himself visible on the other bank of the stream, wielding his bow and arrow and showing that he is always ready to react. But he was actually after food: “I’ve been trying to catch this tucunaré [peacock bass] for two days, man!”

The chief said he was not aware that plots of land in his village had been sold on the internet, but he remembers that Nemus was in the area claiming to own the land. The company promised to develop projects with Indigenous people, creating jobs and promoting improvements in the villages, but always ignoring the recognition of their traditional territory.

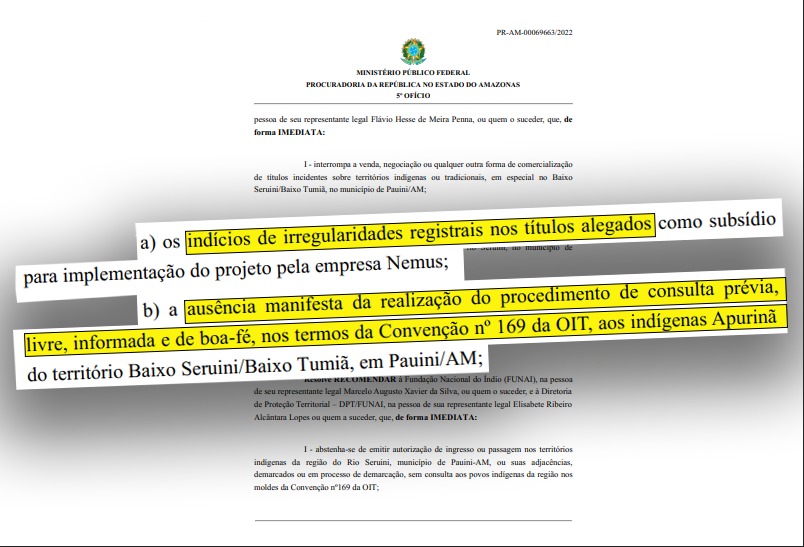

In December 2022, the Federal Prosecution Service (MPF) recommended the suspension of Nemus’ project — a view shared by Brazil’s National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI). But none of the agencies knew the company had sold parts of the territory as NFTs, much less that they were still being traded, as InfoAmazonia found out.

In September, our team visited the villages of Penedo, Kamarapa, Maloca and Bom Jesus in the Lower Seruini/Lower Tumiã and Marienê Indigenous lands, which are directly impacted by the project announced by Nemus.

The reporters found 1,482 areas in the Apurinã Indigenous land registered as NFTs, which are digital certificates of ownership of unique (non-fungible) assets such as works of art, collectibles or properties. In this case, buyers make virtual purchases of plots in the territory, which they can sell to others anytime. It works like a stock exchange. NFT prices vary according to the prices of encrypted virtual money — cryptocurrencies — and the value of the environmental asset that is supposed to be contributing to preserve the forest. At least 665 clients purchased forest land plots and continue trading them as NFTs on specialized platforms.

According to Nemus, NFT holders can navigate the area they acquired and detect wildlife or environmental threats, monitoring and auditing the conservation of the area.

Map displays, in gray, the points identified by the report with NFTs registered on Nemus servers. Each point represents an NFT. On the map, click on each of them to view attributes and the URL leading to each token on the company’s website. Hover over the yellow points to see information about areas of interest to indigenous communities. Select the layer in the top right corner to view the approximate area of the Baixo Seruini territory.

This report is part of the series ‘Money Grows on Trees: Financialization of the Forest Pressures Indigenous Lands,‘ which investigates contracts with suspected violations of indigenous rights in traditional territories of the Brazilian Amazon.

The timber business

Nemus said it purchased the land from Manasa Madeireira Nacional S.A. (Manasa) and that its project is not located on Indigenous lands. It also claimed the mission of its NFTs was “forest conservation.”

Manasa has been on the list of the biggest Amazon deforesters and has been charged with environmental crimes in 35 public civil actions.

The areas offered by Nemus as NFTs range from 0.25-81 hectares (0.6-200 acres). The project also includes the exploitation of 200,000 Brazil nut trees in the area the company claims to own, with a processing plant to export the product using Indigenous labor. There are also plans for building roads and landing strips as well as mechanizing harvesting.

Furthermore, according to the company, project investors can use the areas to generate carbon credits. At no point has Nemus presented itself as a carbon credit company, but it has guaranteed this possibility to so-called “sponsors” — customers who get the largest shares of NFTs.

Under the project’s budget, Nemus even purchased a boat for the Amazonas State Police in the municipality of Pauini to improve security in the region and prevent invasions of NFT areas. The Indigenous people received brush cutters from the company to open paths to chestnut groves.

Nemus’ businesses are associated with European investors and ASF BRAZIL LTD, a London-based holding company founded by Italian businessman Maurizio Totta. In Brazil, Totta is a partner of Pedro Ruhs da Silva and Flávio Meira Penna, who appear as owners of Nemus and other companies in partnership with ASF. The group’s main investments in the Amazon are focused on timber extraction, with the recovery of bankrupt or indebted companies.

In an interview on American TV in the Break It Down Show, Nemus’ founder Meira Penna said the Indigenous people “are sort of like squatters” in the areas acquired by Nemus, but he stated that “they’ll live there forever” and “they will jump to the digital world very quickly.”

In the video, which can be seen in full on YouTube, the businessman details his NFT project in the area claimed by the Indigenous people. The deal is meant to raise up to $5 million, with NFTs selling for $150-$51,000. With that money, Nemus would buy more areas in the region to launch more NFTs, as explained in the video.

In addition to Manasa, Meira Penna also acquired a timber company, Laminados Triunfo, in Acre state and exported the product to the U.S. In April, the company was the target of a “timber laundering” investigation by the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA).

Indigenous people were not consulted

The land traditionally occupied and claimed by the Apurinã for decades was only recognized by FUNAI in 2017, when identification studies began, but the demarcation process was never completed. “What we want is for our territory to be demarcated so we feel safer,” Chief Kaiaxi said.

The villages of the Seruini Stream have no electricity or internet services. According to the Indigenous people, the lack of basic facilities was crucial for Meira Penna and his staff to promise improvements to the communities, such as better health care and schools for the youth. The first contacts took place in 2021, during the pandemic, and were authorized by FUNAI under the administration of former President Jair Bolsonaro (PL), violating the agency’s own rules that prohibited non-Indigenous people from entering communities due to COVID-19.

“They said they were coming to help us; they took photos of the nut trees to check the production, but when they came back, they were telling a whole different story,” Chief Kaiaxi said.

They said they were coming to help us; they took photos of the nut trees to check the production, but when they came back, they were telling a whole different story.

Chief Kaiaxi of Penedo village

In fact, the Indigenous people were never properly consulted about the company’s plans, much less did they know that the lands they inhabited were being sold as NFTs that promised to preserve the Amazon.

According to the prosecutors, the lack of prior, free and informed consultation as provided for in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) “shows alleged violations of the rights of communities,” which led to an investigation started in July 2022.

ILO Convention 169 provides for the right to consultation on any project that interferes with Indigenous lands. Regardless of whether or not the territory has already been officially recognized, the entire recognized Indigenous community must be aware of what is being proposed and has the right to approve the project or not. The matter must be discussed internally by the Indigenous people, with the adoption of a consultation protocol that allows everyone in the territory to have access to information about the projects.

To the Prosecution Service, Nemus said the property was not on “actually demarcated Indigenous land,” and therefore the company’s understanding was that “no article of ILO 169 convention on consultation applies.”

In the same document from August 2022, Nemus said it was not yet developing economic activities in the area. However, at the time, the company had already launched its NFTs on the market, for which sales began in March 2022.

Company changed name of Indigenous land to NFT

According to information from Indigenous people who live in the area, Nemus managed to persuade the chief of one of the villages to accompany representatives of the company to the municipal notary office in Pauini and change the name of the area the company claims to own to “NFT.” Other Indigenous people told InfoAmazonia they had only become aware of the change after it had taken place, without the knowledge of the other chiefs and the community. In an institutional video made by Nemus itself, it is possible to see that the Indigenous man who signed the document used his thumb, which indicated that he could not write. He did not want to speak with the reporters.

With the change, the entire area that Nemus claims to own, including Kamarapa and Penedo villages, is now called Non Fungible Territory (NFT).

Chief Teixeira de Sousa Lopes Apurinã from Kamarapa village, which is close to Penedo, complained about lack of transparency on the part of Nemus and said the company arrived in the area offering help, but never spoke about how the NFT project would work.

“They came here, recorded a video with us and handed over a sign, but they never really explained the project; they just told us they’d help us,” he said, pointing out that, because of their needs, the Indigenous people accepted help from the company.

They came here, recorded a video with us and handed over a sign, but they never really explained the project; they just told us they’d help us.

Chief Teixeira de Sousa Lopes Apurinã from Kamarapa village

“I made a list of things we needed — machetes, sharpeners — and I said we needed improvements at the local school, internet … but not so that we’d be bossed around by them,” said Teixeira.

“We’d like the governments themselves to recognize our situation. My grandfather was a chief, my brothers are chiefs, I’m the chief of this village, but we feel forsaken. We are not asking; we are demanding something that is rightfully ours. We own this place, we came from this land,” the leader added.

We’d like the governments themselves to recognize our situation. My grandfather was a chief, my brothers are chiefs, I’m the chief of this village, but we feel forsaken. We are not asking; we are demanding something that is rightfully ours. We own this place, we came from this land.

Chief Teixeira de Sousa Lopes Apurinã from Kamarapa village

As a way of protecting themselves and reinforcing traditional land use, the Apurinã created an ethno-environmental map where they located important points of community use, such as nut groves, areas of clay collection for ceramics, hunting areas and waterfalls, for example. Each village mapped its perimeter of use, which formed the area required for final demarcation of the territory.

176,000 reais ($35,700) in an NFT from the Gênesis project

Each NFT from the Gênesis project is represented by a virtual card with the image of what exists in the area acquired, such as jaguars, sloths, king vultures, toucans, trees and fruit. The card informs the size of the area and its geographic coordinates.

Among the project’s 1,482 NFTs found within the land of the Apurinã, Gênesis’ tokens were traded on specialized platforms such as Coin Base NFT,LooksRare and OpenSean. Prices are quoted in cryptocurrencies, ranging from $17-$603.

The highest transaction on a single NFT found by the reporters was worth 19.44 WETH, equivalent to 176,000 reais ($35,700) in current values of that cryptocurrency quoted Nov. 1, for an area equivalent to 89 hectares (220 acres). The first sale of this specific token took place in February 2022, in a pre-sale operation. According to the company, the Gênesis collection was officially launched in March 2022.

In May, for the first time, Nemus publicly admitted that “there is a dispute” in the Gênesis project area, which was “temporarily suspended and will be resumed with a new property in the Pauini region.” In the same statement, the company said it was negotiating areas with the Xerente Indigenous people from Tocantins.

The areas in Pauini to which the company referred would be adjacent to the current project and, according to the Indigenous people themselves, are also part of the Apurinã territory.

In the statement, the company said the problem involved “the owners” with whom they had “an irrevocable agreement to purchase the property.”

The information is on a Nemus blog on the Medium platform. On the company’s official website, there is no mention of the suspension of the project or what will be done with those who have already purchased NFTs.

Although the sale of NFTs from the Gênesis project appears unavailable on the Nemus website, on the Ethereum platform, which records token deals, it is possible to find recent NFT negotiations that point to Indigenous lands, which is against the Prosecution Service’s recommendations.

Nemus insisted, but FUNAI denied entry into territory

In January this year, FUNAI’s new management interrupted its contact with Nemus that had begun during the Bolsonaro administration. According to the agency, “the lack of regulation of NFTs in the country is a problem,” especially because the territory is still in the process of demarcation, “creating legal uncertainty in an area with a history of persistent embezzlement involving Madeireira Nacional S.A. (Manasa) and conflicts with non-Indigenous people,” FUNAI said in a statement.

The agency claims that, as of January this year, Nemus still “insisted on holding meetings with the Apurinã,” but the request was denied.

In December 2022, the Prosecution Service recommended halting “sales or negotiation” of the Nemus project. The agency also recommended that FUNAI refrain from “authorizing entrance into or crossing Indigenous territories.”

According to the prosecutors, “treating Indigenous peoples who have been claiming their territorial rights for decades — with demarcation procedures underway at FUNAI — as squatters shows, at the very least, lack of respect for the rights claimed by those peoples and guaranteed by the Constitution,” as stated in the recommendation issued by Prosecutor Fernando Merloto, which also said that “in case of failure to comply with the measures, beneficiaries and management will be held responsible for their commissive or omissive conduct.”

Given the evidence that areas of the Indigenous territory were sold as NFTs, contrary to what Nemus informed the prosecutors, FUNAI said it would denounce it to the Prosecution Service “as soon as it obtains proof of these virtual sales.” InfoAmazonia shared the data from the investigation with the prosecutors, who promised to comment on the case soon.

Nemus and SFA did not respond to our emails requesting clarification until this publication was closed. We were unable to contact businessmen Meira Penna and Totta.

Persecution cycles

Madeireira Manasa arrived in the Lower Seruini region in the 1970s, during Brazil’s military dictatorship and obtained a document from FUNAI saying were no Indigenous villages in the area, which disregarded the presence of the people who already lived there.

During that period, more than 800 non-Indigenous people were taken to the Lower Seruini region, triggering conflicts. It was at this time that José Lopes Apurinã was murdered during an ambush. He was the grandfather of Chief Dário Lopes Apurinã, known as Kacuiry, from the village of Bom Jesus. The conflict left several people injured. One of the chief’s brothers still lives with permanent injuries.

The first contacts with the Apurinã took place in the 18th century, during the race forforest commodities – cacao, copaiba oil, turtle butter. In the following century, the rubber cycle exposed the violence. To escape, the Apurinã remained in more hidden areas of the forest, close to streams. This allowed some groups to stay completely isolated as they wanted until the 1940s, when a new rubber cycle intensified with the “rubber soldiers” during World War II.

When Manasa arrived, Kacuiry recalled, once again the Apurinã were cornered. “A lot of people came; they stayed here killing game and our fish. When they built the farm, things got ugly for us. They said we weren’t entitled to anything, and we fought back,” he recalled.

Despite their family and cultural connections with the others in the Lower Seruini area, Bom Jesus village is located within the Seruini/Marienê Indigenous land, where in 1914 there was already a post of the Indian Protection Service (SPI), installed to appease disputes between Indigenous people and rubber tappers. The area was closed for studies in 1986 and officially approved in 2000. But the communities in the lower part of the stream were left out of the studies.

According to FUNAI reports, most communities in the Lower Seruini area descend from the marriages of old Jacinto with three sisters originally from the Tumiã River region. Therefore, the areas of the Lower Seruini and Lower Tumiã are currently occupied by related families. Despite being dispersed, according to researchers, this group forms an Apurinã occupation network in the area of Igarapé Seruini.

This report is part of the series “Money that grows on trees: Financialization of the forest puts pressure on Indigenous lands,’ produced by InfoAmazonia with support from Journalismfund Europe, through Report for the World, and in partnership with Mongabay.