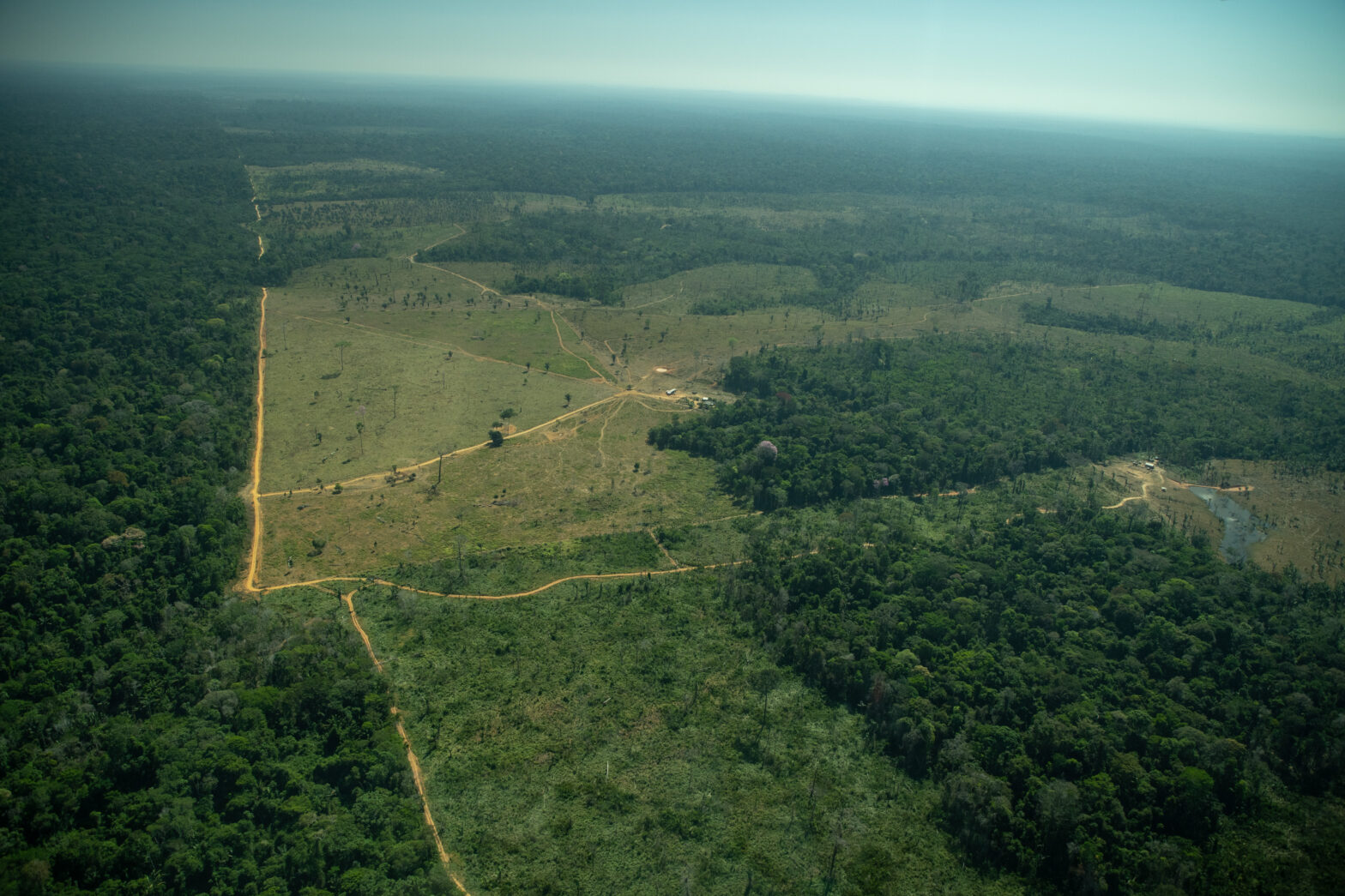

In addition to the area targeted for livestock, nearly 40% of the forest affected by the 2019 arson is still unused and was burned ‘for the sake of burning.’

Three years later, 61% of the forest area burned on the “Day of Fire” in São Félix do Xingu, Altamira and Novo Progresso, in the Brazilian state of Pará, has turned into pasture. However, not everything that burned became space for livestock: 37.4% of the affected forest area remains forest, but is now degraded.

These municipalities are among those where the most forests burned in the criminal action of the Day of Fire, August 10, 2019, when groups of ruralists coordinated on WhatsApp to set fire to the Amazon from the edges of Interstate BR-163.

Located over 1,600 kilometers from the epicenter Novo Progresso, Porto Velho (Rondônia) is third on the list, followed by Lábrea (Amapá), a distant neighbor:

Of the ten municipalities that saw the most forest burned in the episode, Lábrea recorded the highest conversion to pasture: 91.53% of the area that caught fire in the municipality in 2019 has become pasture. The lowest conversion was registered in Arame (Maranhão), with 10.62% of the burned area transformed into pasture and the remaining 89% turned into degraded forest.

In São Félix do Xingu, 48.7% of the burned area has become pasture and 49.8% turned into degraded forest. In Altamira, 75.44% of the area was converted into pasture and 23.13% is now degraded forest: Partial and gradual elimination of forest vegetation for the selective extraction of wood and other natural resources. It can also occur due to fire and climate change.; in Novo Progresso, 67.15% has become pasture and 31.37% degraded forest.

The analysis was conducted by researchers from the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), with data from the Monitor do Fogo, a monthly survey of fire scars in the country, and MapBiomas, an annual survey of land use and coverage. The data refers to the changes detected between 2019 and 2021 - conversion data for 2022 and 2023 are not yet available.

The results are available in an interactive panel. It is possible to select the display by states, municipalities, indigenous lands and conservation units.

Boca do Acre

The municipality of Boca do Acre (Amapá), located 2,300 kilometers from Novo Progresso (Pará) and just over 200 kilometers from Rio Branco (Acre), is the most distant among the 20 with the largest areas of burned forest. If you follow the list, the cities of Feijó and Sena Madureira, both in the state of Acre, also appear.

Although the criminal action of the Day of Fire was concentrated in Pará and Mato Grosso, four other states of the Legal Amazon: A region that occupies almost half of Brazilian territory, covering nine states, and has an area greater than that of the Amazon biome. recorded fires of large proportion: Amazonas, Rondônia, Acre and Maranhão.

"The fact that these fires have reached this far, from a crime coordinated by groups from Novo Progresso, only shows that the people who set fire to the forest mainly targeted the Brazilian Amazon, especially in states with a high concentration of indigenous lands and protected areas," says Ane Alencar, director of Science at IPAM.

The fact that these fires have reached this far, from a crime coordinated by groups from Novo Progresso, only shows that the people who set fire to the forest mainly targeted the Brazilian Amazon, especially in states with a high concentration of indigenous lands and protected areas.

Ane Alencar, director of Science at IPAM

Of the six states with the most burned forest at the time, Amazonas was the one with the highest conversion rate: 76.71% of the burned forest became pasture, while 21.69% turned into degraded forest.

Maranhão was the state whose burned forest area changed the least: 24.17% became pasture and 74.9% degraded forest.

Fire by fire

In all the states of the Legal Amazon: A region that occupies almost half of Brazilian territory, covering nine states, and has an area greater than that of the Amazon biome., there were over 11,500 km² of forest burned from the Day of Fire. Of this area, about 6,000 km² (52.3%) became pasture, while another 46.6% gave way to degraded forest. The portion draws attention from researchers.

"The behavior observed after burning is normally a change in land use, either with conversion to pasture or agriculture, for example. But we see that the areas of forest burned on the Day of Fire have not met the same fate, or at least not yet. So far, the images show us that much of the forest areas were burned ‘for the sake of burning,’ without necessarily having any use afterwards, not even an illegal one," explains Felipe Martenexen, a researcher at IPAM who conducted the analysis.

The behavior observed after burning is normally a change in land use, either with conversion to pasture or agriculture, for example. But we see that the areas of forest burned on the Day of Fire have not met the same fate, or at least not yet. So far, the images show us that much of the forest areas were burned ‘for the sake of burning,’ without necessarily having any use afterwards, not even an illegal one.

Felipe Martenexen, researcher at IPAM

Traces of illegality in the action are more evident with the data of burned forest in indigenous lands: Territories of the Union recognized and delimited by the federal government in order to maintain the indigenous way of life and culture throughout the country. and conservation units: Territories designated for the maintenance of ecosystems and natural resources for society as a whole and delimited, managed and protected by the public authorities..

If it were a city, Urubu Branco would take Porto Velho's place as having the third largest area of burned forest. The indigenous territory inhabited by the Tapirapé people, in the northeastern region of the state of Mato Grosso, is close to the Xingu Indigenous Park. The latter, inhabited by 16 peoples, has the second largest area of burned forest out of the indigenous territories.

The Triunfo do Xingu Environmental Protection Area would also surpass Porto Velho: a conservation unit with the largest area of burned forest, located in the municipalities of São Félix do Xingu and Altamira.

What remains from the flames

“The biggest impact we see is on health. It really stings the eyes, especially in children and the elderly. They get sick. The smoke penetrates our homes and it gets very hot, hard for us to sleep. We can't collect fruit and food, because all of it was burned up. Since the animals run far from the fire, it's also difficult to hunt. The red-footed tortoise is one that has disappeared from our region. We used to have lots of them. Even the birds have vanished, ”says Paroo'i Tapirapé, chief of the Myryxitãwa village, one of eight in the Urubu Branco Indigenous Territory.

The biggest impact we see is on health. It really stings the eyes, especially in children and the elderly. They get sick. The smoke penetrates our homes and it gets very hot, hard for us to sleep.

Paroo'i Tapirapé, chief of the Myryxitãwa village

After 2015, Paroo'i recalls, the source of a tributary of the Tapirapé River began drying up every year. "This water had never dried up before, but now we're seeing it all the time. Every year, there are more effects from the fire. It is very destructive. The more burning, the droughts,” he reports.

"Another strong impact is in terms of culture: we can no longer find the leaves of wild bananas, of bacaba, not to mention the specific woods that we used to build the Takãra, the Apyãwa ceremonial house. In our land, the roofs of people's homes are made of coconut leaves. If we burn everything, we're not going to have any more new houses,” he adds.

The eight villages organize actions to prevent and combat the fires that have entered the territory. Groups trained by the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples: FUNAI, a federal agency created in 1967, responsible for implementing policies to protect and promote indigenous rights throughout Brazilian territory. and with the support of the Fire Department operate on indigenous land. At the school, headquartered in the main Tapi 'itãwa village and with rooms in the others, over 300 children and teens learn about the relationship between fire and nature.

The areas affected by the fire are concentrated in the north of the indigenous territory, which may indicate the presence of invasions and land grabbing: Illegal occupation of public lands through the falsification of documents.. As the fires tend to get close to villages in this region, the community wants to institute indigenous brigades in order to control them.

“We try to fight the fire from far away, but it's very difficult. As long as there's no rain, the fires continue until they reach the village. The neighboring communities, and even the farmers, also have to do their part. If we do our part, but they don't so theirs, then there's no use. We're all responsible,” says the chief.

More days of burning

Days with even more fire in the Brazilian Amazon occurred after 2019. That year, there were 30,900 hot spots in August and 19,900 in September, according to data from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Meanwhile, the years 2020 and 2021 maintained the same level and, in some cases, even exceeded it. But the year 2022 went even further.

In 2022, there were over 33,000 hot spots in August and 41,000 in September, more than double that of the same month in 2019. The smoke that permeates the daily lives of the Amazon's populations has once again reached the Brazilian Southeast and countries such as Bolivia and Peru. It was the largest record of outbreaks in the biome since September of 2007.

The explanation might be found on the calendar of institutional politics. Scientists estimate that the occurrence of fires and deforestation usually increases in election years, as was the case in 2022. The diversion of the government's attention leads to a weakening of oversight, which paves the way for environmental crimes.

São Félix do Xingu and Altamira maintain, in that order, the largest area of forest burned in 2019 and 2022, between August and October. Of the ten cities with the most burned areas in 2019, they also repeated the feat in the same period last year: Porto Velho, Lábrea, Apuí (Amapá), Novo Progresso and Colniza (Mato Grosso). Marcelândia, Peixoto de Azevedo and União do Sul, municipalities of Mato Grosso, are newly featured on the list.

Prevention and recuperation

The presence of fire in the Amazon is directly related to human interference. Fire does not occur in the forest without agricultural operations or deforestation. In the former case, the application of fire in an attempt to “clear” an area can get out of control and become a forest fire. In the latter, fire is part of a stage of the deforestation process.

According to MapBiomas Fogo, 19% of the Brazilian Amazon was burned on at least one occasion between 1985 and 2022. This constitutes 809,000 km², an area larger than the state of Minas Gerais. About 68% of that total was burned more than once. And if there's a place, there's also a time: 75% of fires occur between August and November, during the “burning season,” characterized by a dry period in most of the biome.

The application of Integrated Fire Management (IFM) strategies can reduce the risk of the fire spreading, combined with the control of fire use. In the Amazon, IFM includes the mapping of vegetation and risk areas, the formation of local fire brigades and the creation of barriers to the passage of fire, known as firebreaks.

Measures to control deforestation and forest degradation are also reflected in the reduction of burning, since fire is one of the main components of these processes. The first phase of the PPCDAm (Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon), for example, reduced the burned area by 46% between 2004 and 2012.

“The process of recuperating degraded forests is slow and the problem is that the more degradation, the more likely new disturbances are to occur, which makes recuperation even more difficult. To avoid this risk, the first step in recuperating a forest is precisely to protect it, preventing new disturbances from taking place," says Alencar, who also coordinates the MapBiomas Fogo network.

How the analysis was conducted

The analysis developed for this report used data from the Monitor do Fogo, on monthly burned area, and MapBiomas Brasil (Collection 7.1), on land cover and use - these surveys are the most recent available and go until 2021. As such, they do not include changes that may have occurred in 2022 and 2023. Satellite images from 2018 were used to compare with the forest cover prior to the Day of Fire.

This report is the result of an exclusive partnership between the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) and InfoAmazonia, published specifically as part of the project PlenaMata.