Analysis of data from the Geo-Yanomami group shows that, in addition to mining, the territory also has records of deforestation. The problem is driven by advances of agribusiness.

The advance of the agricultural frontier in the east of Yanomami Indigenous Territory (TIY) and the rise in deforestation: Total elimination of native vegetation in a given area, generally followed by occupation with another land cover or land use.alerts in its surrounding area increased the immediate risk to the health of local populations, according to a new survey (read more below). Agribusiness’s interest in the territory is nothing new, but it has intensified in recent years, despite several complaints made by indigenous organizations.

According to Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa, the cattle ranches that have invaded the east of the indigenous territory were first denounced by the Hutukara Yanomami Association almost 10 years ago. However, many of the invaders remain in the region and, in some cases, new deforestation alerts indicate that their grazing areas are expanding.

“We often denounce the farms that are destroying our land, but the authorities don’t listen,” says Kopenawa, president of the Hutukara, the main indigenous entity in the region, created in 2004 to defend the physical integrity of the TIY residents and all of their natural resources.

The authors mapped out how forest degradation: Partial and gradual elimination of forest vegetation for the selective extraction of wood and other natural resources. It can also occur due to fire and climate change. and deforestation have advanced in the TIY in recent years. Unlike deforestation, which is the total elimination of native vegetation in a given area, forest degradation is the partial and gradual elimination of vegetation in a process that can occur, for example, from selective logging, fire, edge effects and drought.

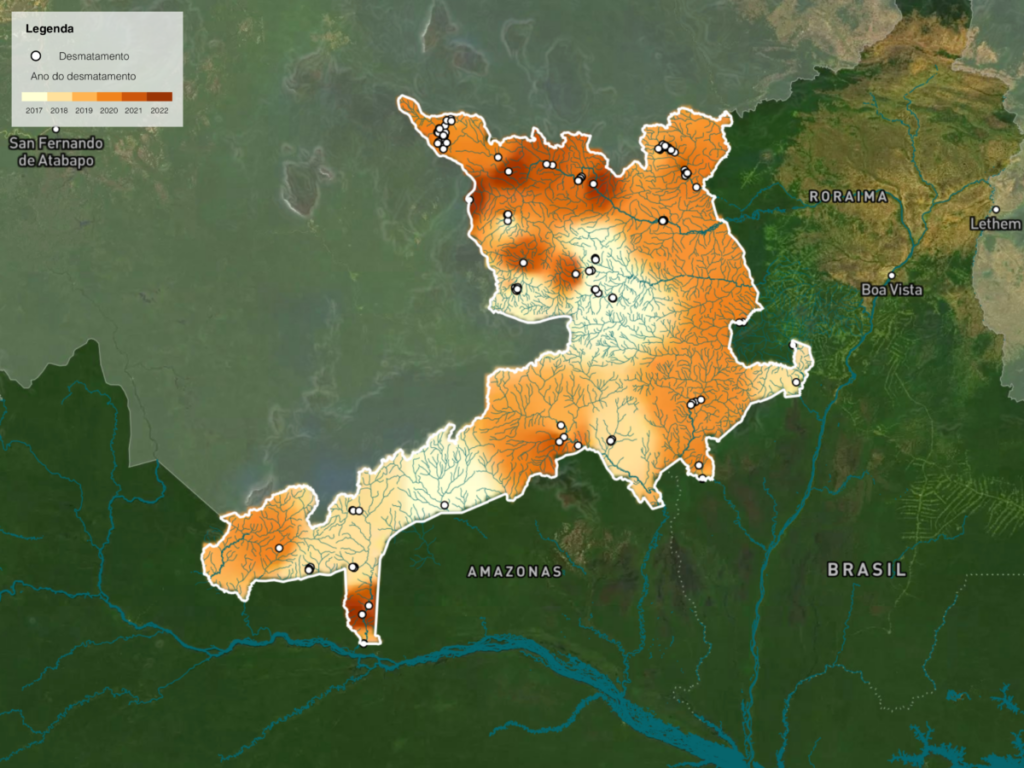

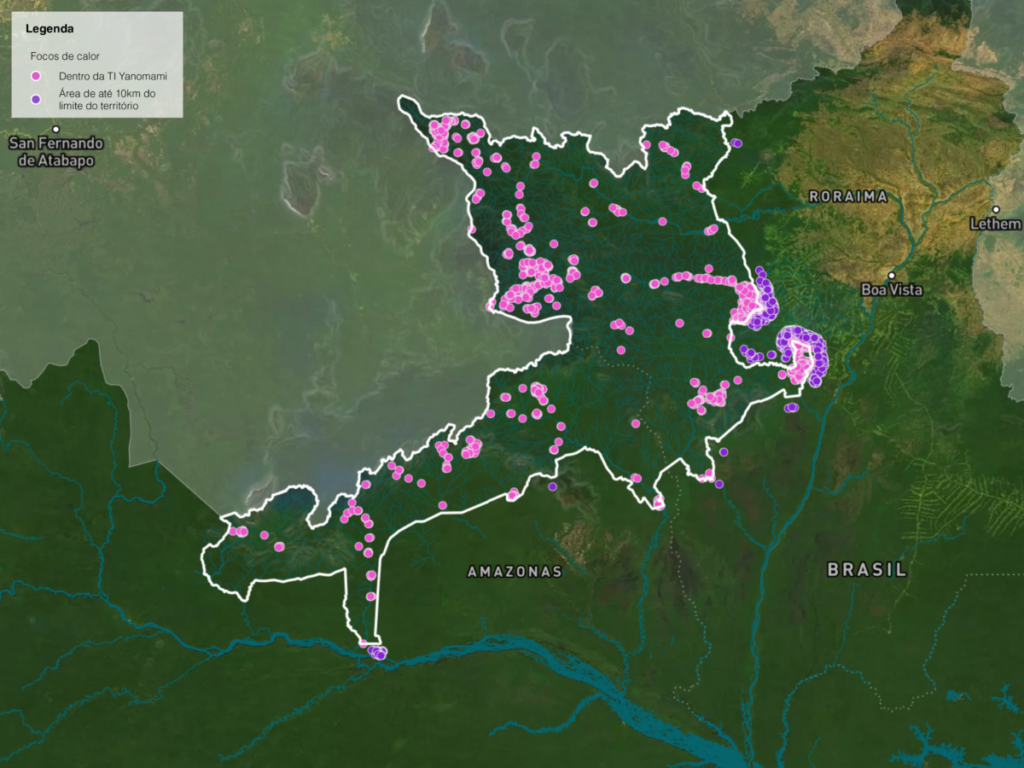

In the case of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, changes in vegetation cover through a combination of deforestation, mining and burn scars were measured by Deter, a rapid surveying system for alerts of evidence of forest cover change in the Amazon. The analysis concluded that over 729.45 km² had changes of this type between 2017 and 2022. The researchers evaluated the entire period available for analysis by Deter, a monitoring system that was created shortly before, in 2016. The TerraClass System, responsible for qualifying deforestation in Brazil’s Legal Amazon, also indicated that between 2017 and 2020, new areas in the eastern region of the reserve were transformed into pasture.

Furthermore, scientists highlight the differences between the change in the vegetation cover that occurs due to the advance of agribusiness and the logging activity of the indigenous people themselves, who, when moving through the territory, create small clearings in different regions.

The fires were the main changes observed, both in frequency and in the total altered area. Among the 729 km² with alterations, over 700 km² were linked to fire in the TIY. Compared to the clearings, they are larger, more elongated areas that usually accompany the river beds or the course of roads, whether they be legal or illegal. Meanwhile, the clearings, observed in small numbers, occupy smaller areas and are circular in shape.

According to the researchers, fires in peripheral areas of the TIY, such as the east of the territory, which is close to more structured roads, “may be related to logging and the formation of land for use in pastures or large-scale agricultural operations.”

Changes in land use

One of the explanations for the increase in the area subjected to forest cover changes in the territory is the advance of agribusiness in the far east of the indigenous territory, the portion closest to the city of Boa Vista.

“Although the Yanomami Indigenous Territory is known most for the conflict with miners, there is also the threat of land grabbers, that is, farmers who invade the demarcated area,” explains Ana Rorato Vitor, coordinator of deforestation analysis for the Geo-Yanomami group and researcher at the Laboratory of Investigation in Socio-environmental Systems (LISS) of the INPE.

Although the Yanomami Indigenous Territory is known most for the conflict with miners, there is also the threat of land grabbers, that is, farmers who invade the demarcated area.

Ana Rorato Vitor, coordinator of deforestation analysis for the Geo-Yanomami group

The researcher states that data obtained via satellite image shows that many of the deforestation alerts that hit the IT appeared within the limits of the territory and advanced into the demarcated area in the east of the reserve.

“The threats that take place outside the boundaries enter into the territory. Although indigenous territories are one of the best barriers to deforestation, they are permeable. What changes is the time it takes to penetrate them. If you have a government that for years has tried to legalize mining and endorsed activities that promote deforestation, you have an acceleration of this process,” Rorato adds.

The threats that take place outside the boundaries enter into the territory. Although indigenous territories are one of the best barriers to deforestation, they are permeable. What changes is the time it takes to penetrate them.

Ana Rorato Vitor, coordinator of deforestation analysis for the Geo-Yanomami group

The state of Roraima is considered the last agricultural frontier in the country. The only federal unit that is not connected to the national electrical grid, Roraima depends on energy imported from Venezuela and thermoelectric plants that are highly polluting.

This isolation, combined with the protection guaranteed by the indigenous reserves located in the area, meant that the state was less targeted by farmers during the process of expanding arable territories in the north of the country.

“Considering the complexity of the Amazon, it is much more difficult to access this area because it is so distant and isolated. The deforestation and then the fires that happen in indigenous territories are followed by invasion. One feeds the other and then comes the pasture and grain planting,” explains Martha Fellows, researcher and coordinator of the Indigenous Center of the Institute of Environmental Research of the Amazon (IPAM).

Considering the complexity of the Amazon, it is much more difficult to access this area because it is so distant and isolated. The deforestation and then the fires that happen in indigenous territories are followed by invasion. One feeds the other and then comes the pasture and grain planting.

Martha Fellows, researcher and coordinator of the Indigenous Center of the Institute of Environmental Research of the Amazon

“In the region of Roraima, this sequence does not occur so easily because, economically speaking, it is an invasion that is not always justified. There are other areas of the Amazon that are more targeted for this,” the researcher adds.

The advance of agribusiness

Despite the difficulty of access reducing the interest of agribusiness, data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) show that the agricultural frontier is already advancing in Roraima.

The soybean farming area in the state went from about 47,000 hectares in 2017 to over 100,000 hectares in 2021, according to the Municipal Agricultural Survey. The cattle herd went from about 787,000 heads in 2017 to almost 938,000 heads in 2021, according to the Municipal Livestock Survey.

All the municipalities in the state of Roraima that make up the TIY have shown an increase in cattle production in recent years, according to the technical note from the Geo-Yanomami group produced with data from the IBGE. Two cities that have more than 70% of their area within the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, Alto Alegre and Iracema, had the greatest proportional increase in soybean planting area in the entire state.

The presence of farmers in the east of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory began even before the definitive demarcation of the territory. The Hutukara Yanomami Association has been denouncing the operations of land grabbers in the region for more than 20 years, and its president, Davi Kopenawa, has been the subject of death threats for asking the federal government to remove the farms.

“We began many years ago denouncing the man who destroys. We issued several reports. It was only in 2014 that we managed to get Paludo out. But we only got one of them: there are still other farmers invading there,” says Kopenawa.

The Yanomami leader is referring to the departure of Ermilo Paludo, a cattle rancher who maintained farms within the territory for decades. In an interview with a local newspaper in 2013, Paludo confirmed that he had upwards of 3,000 cattle in the IT.

Finally, in 2014, after signing an agreement with the Federal Public Ministry (MPF), Paludo left the indigenous territory and was compensated for the occupation, recognized by the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) as having been established prior to the demarcation. According to the agency, 12 illegal farms in the IT were removed that year.

Despite having gained the most notoriety, Paludo’s farms were not the only ones that advanced in the region: data on deforestation and changes in land use from the Prodes and TerraClass systems show new pasture areas that emerged in the territory between 2017 and 2020.

The mapping of these areas indicates that massive and continuous deforestation is occurring mainly at the edges of the roads that lead to Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima, and close to the borders of the indigenous territory, explains Christovam Barcellos, a researcher at Fiocruz and one of the creators of the Geo-Yanomami group.

Head of the Health Information Laboratory of the Institute of Communication and Scientific and Technological Information on Health (LIS/ICICT), Barcellos believes that the work of systematizing Geo-Yanomami data can help guide new humanitarian actions in the region. According to him, the mapping of illegal mining and deforestation leads to a better assessment of the ongoing lack of assistance.

“There were a lot of people going to the humanitarian actions who were lost, not knowing what was going on. When you go to a certain property, you have to know where you’re going, where there’s an airstrip, where there are roads, to maintain the supply chain and have escape routes, because there could be a conflict, perhaps even with armed groups. There needs to be a strategy for occupying the territory, and there was none,” says Barcellos.

The collection and systematization of information, which involved cross-referencing various databases and satellite images, can also help reduce the criticism that has been directed thus far at actions in humanitarian aid. The lack of dialogue with local leaders and knowledge of the regional reality are the main problems indicated in these initiatives, considered insufficient by Yanomami leaders.

Humanitarian aid

The flaws in the humanitarian aid actions organized thus far are already public knowledge: in June, a report by Agência Pública revealed that the Ministry of Defense alleged there was not enough money and asked FUNAI for over R$16 million to take food donations to the Yanomami communities. The food has not reached its destination and the delivery of thousands of baskets of basic food supplies remains paralyzed.

In a note sent to our reporters, the Ministry of Defense said that FUNAI had still not relayed the amount requested, stating that it did not have its own resources for the work and that the baskets “are the responsibility of FUNAI.” InfoAmazonia contacted FUNAI for an update on the status of the delivery of supplies, but had not received a response at the time of this article’s publication.

At the end of the same month of June, a delegation organized by the Ministry of Defense flew over Yanomami territory without prior authorization from the indigenous people and without consulting local leaders. The expedition was the motivation for the publication of a collective notice of repudiation signed by the Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY), the Yanomami Association of the Cauaburis River and Tributaries (AYRCA), the Yanomami Kumirayoma Women’s Association (AMYK), the Wanasseduume Ye’kwana Association (SEDUUME), the Kurikama Yanomami Association (AKY) and the Xoromawë Indigenous Association. The letter calls on the government to work together with local leaders to reverse the invasion of miners and proposes changes in the way humanitarian aid is conducted.

“The government needs to work in a truly integrated and urgent manner, with well-planned actions so that there be sufficient removal of invaders to end illegal mining,” the organizations affirmed in the notice.

Population at risk

At least 17,000 indigenous people are at immediate risk due to the compromise of the areas where they live. This percentage corresponds to over 62% of the Yanomami population, according to data from the Ministry of Health’s Department of Indigenous Health (SESAI) compiled by the Geo-Yanomami group.

The risk imposed on the lived-in areas was measured by way of an analysis that took into account both the situation of the contaminated rivers and that of the communities threatened by deforestation or forest degradation. The risk to communities was calculated based on an analysis of alerts from Deter, the INPE’s rapid surveying system that detects evidence of forest cover change.

According to the researchers, the number of Yanomami at immediate risk may be even higher than estimated, as many details about the mobility of indigenous people in the territory are still unknown.

“Our analysis of the lived-in area is conservative because we know that many communities have greater mobility in the territories, so the impact may be even greater than what was calculated in the immediate risk indicator,” explains Ana Rorato Vitor of INPE.

According to Kleber Karipuna, director of the Coordination of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), which unites indigenous associations from all over the country, the biggest challenge to solving the demands in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory is the lack of dialogue between the federal government and the organizations that represent the communities.

“There was no collaboration. Even the APIB was left out of the construction of the federal government’s most concrete actions. Local and national indigenous associations need to be involved. This is fundamental to this process,” explains the head of the APIB.

“Our criticism is that what is being done today is insufficient. Even IBAMA has issued several complaints about the number of agents available to cover an area the size of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory,” Karipuna adds.

Our criticism is that what is being done today is insufficient. Even IBAMA has issued several complaints about the number of agents available to cover an area the size of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory.

Kleber Karipuna, director of the Coordination of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB)

Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa says that the Yanomami emergency is still not over and that efforts to combat mining and deforestation on indigenous land still need to be intensified.

“The government needs to continue fighting. It cannot think that the situation of the Yanomami IT is resolved, because we’re the ones to say when it’s over,” says the leader and shaman.

“Illegal mining really entered like a disease and when a disease enters the indigenous land, there is no cure. With hard work, we can minimize it. But if we’re just going to keep talking, without doing the work, the problem is not going to get solved. The disease goes on,” Kopenawa adds.

This report is part of the project PlenaMata and was produced as part of the InfoAmazonia Laboratory of GeoJournalism, conducted with support from Instituto Serrapilheira to promote and disseminate scientific knowledge and an analysis of geographic data in journalistic production.