Study published in the journal ‘Nature’ sought to understand how different parts of the forest respond to drought. The research was led by a Brazilian scientist in partnership with 80 other authors and surveyed the conditions of 540 trees of 129 different species scattered across Brazil, Bolivia and Peru.

The sky was dark and only the moon lit the way when biologist Martin Acosta, from the Federal University of Acre (UFAC), left a settlement in the vicinity of Rio Branco for the middle of the forest. It was 2:30 in the morning and Acosta was accompanied by three other colleagues. They’re the ones who helped him on his mission to climb some of the tallest trees in the Amazon in order to collect samples to be used for scientific research.

This routine, which was repeated dozens of times in 2017, is just one part of the extensive study, led by Brazil’s own Julia Tavares, published in late April of this year in the journal “Nature.” Holding a doctorate in Ecology and Climate Change from the University of Leeds, Tavares worked with Martin Acosta and more than 80 researchers from around the world to survey trees in 11 different locations in the Amazon, spanning Brazil, Peru and Bolivia.

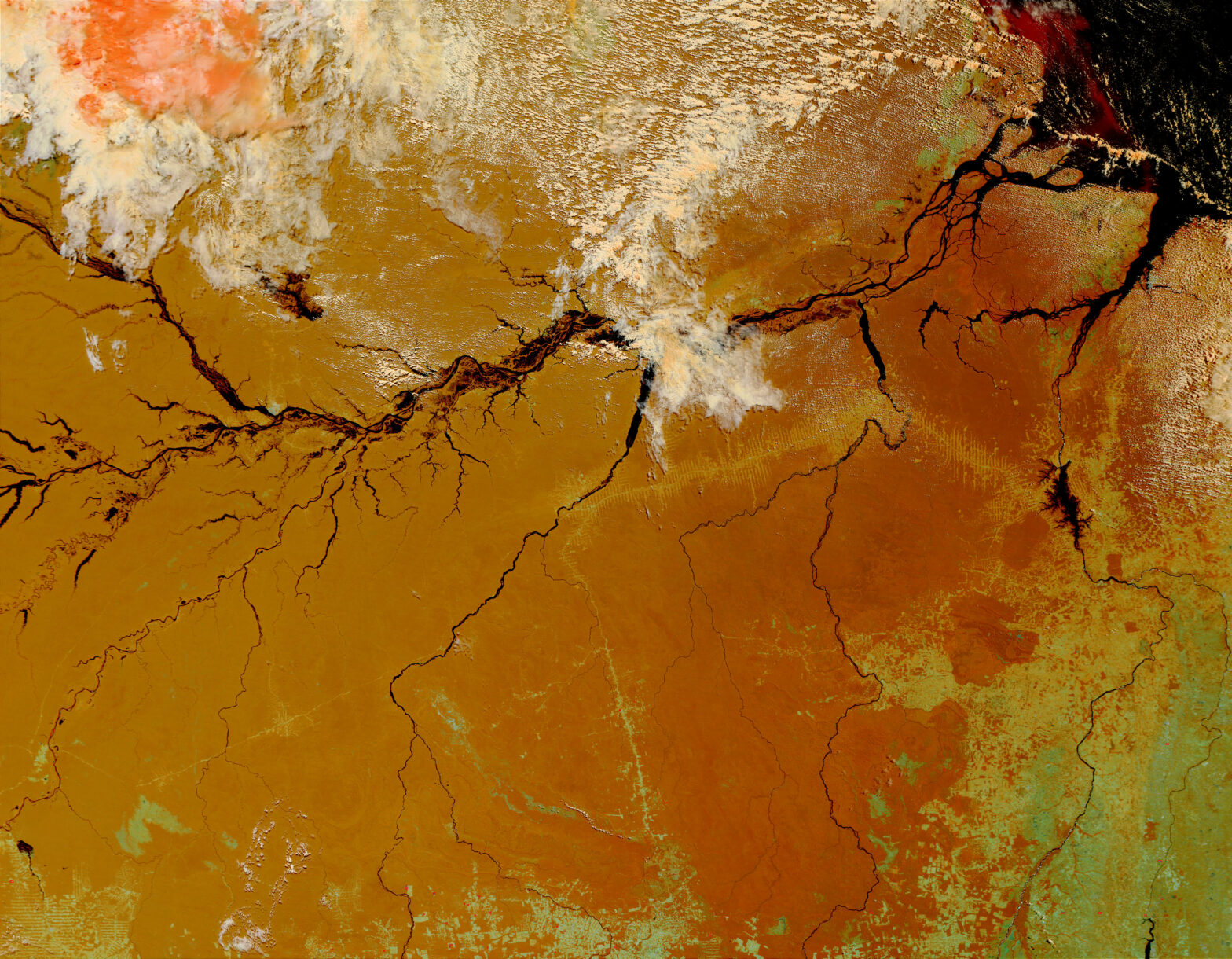

The objective was to understand how the different regions of the forest respond to periods of drought, which are expected to become increasingly frequent and longer-lasting due to climate change. The study showed that the western and southern regions of the Amazon are less likely to withstand periods of low rainfall. Hydraulic failure, which is a leading cause of tree mortality, is more likely in such regions as Peru’s Tambopata National Reserve, and in areas of the southern Amazon, such as northern Mato Grosso.

This conclusion was only possible after a careful survey that evaluated the conditions of 540 trees of 129 different species over several months: “In some of the communities that we visited, people said we were like ‘tree doctors,’ and that we went at dawn because we didn’t want to wake up the plants,” says Julia Tavares, currently a postdoctoral fellow at Uppsala University in Sweden.

“One of the measurements that we took was to see the water pressure inside the trees and understand how stressed they are by drought. The same way we use blood pressure to measure human stress. In trees, we use water pressure,” the author explains.

One of the measurements that we took was to see the water pressure inside the trees and understand how stressed they are by drought. The same way we use blood pressure to measure human stress. In trees, we use water pressure

Julia Tavares, currently a postdoctoral fellow at Uppsala University in Sweden

Researcher Caroline Signori, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Exeter in the UK, says that one of the main conclusions was the confirmation that the Amazon rainforest is actually composed of a series of forests that are different from one other. The biome is not uniform and, as such, actions for its preservation must also be guided according to what is known about each region.

In addition to co-authoring the study, Signori is also the lead author of another article that used the same samples to explain how the non-structural carbohydrates: Those that consist not only of starch, but also of simple sugars, fructans, organic acids, and other less common compounds. of trees can help clarify the differences in the biome.

“Through an analysis of the non-structural carbohydrates of each tree, we can assess the availability of water in the Amazon and have a better forecast of the forest’s responses to future climate change,” says the researcher. The climate emergency causes the rainforest’s capacity to remove carbon from the atmosphere to diminish with the occurrence of droughts, according to the researchers’ analyses.

“In recent decades, we had intense droughts in the Amazon in 2005, 2010 and 2015. These droughts have caused the forest to lose some of its ability to store and stockpile carbon. The way a tree absorbs carbon is by growing, but in a drought, it stops growing and no longer removes carbon,” Julia Tavares explains.

Behind the Research

It is important to show that the western and southern regions of the Amazon are less likely to withstand periods of low rainfall than other areas of the forest, as many scientific studies are conducted only in the central and eastern regions of the biome, which are traditionally more resistant to drought.

“Some areas of Pará where much of the research is conducted today are seasonal forests that are more resistant to drought. So, if you take the value extracted from these studies and apply it to the entire Amazon, you are overestimating the forest’s capacity to withstand drought periods,” explains Tavares.

Some areas of Pará where much of the research is conducted today are seasonal forests that are more resistant to drought. So, if you take the value extracted from these studies and apply it to the entire Amazon, you are overestimating the forest’s capacity to withstand drought periods.

Julia Tavares, currently a postdoctoral fellow at Uppsala University in Sweden

In the southern part of the Amazon, in regions such as northern Mato Grosso, trees showed a greater degree of adaptation to deal with drought. But despite this, the species in this region are at the highest risk of dying in periods without rainfall among all the areas analyzed. According to the researchers, this is because the region has already experienced a reduction in rainfall patterns caused by deforestation, which has pushed the trees to the limit of their capacity.

Meanwhile, in the western region of the Amazon, which spans areas of Bolivia, Peru and the Brazilian state of Acre and has more fertile soils, the trees showed a higher mortality rate due to drought than what was observed in less fertile regions of the central Amazon.

To evaluate this ability to resist drought, the researchers collected samples from the treetops, on branches directly exposed to the sun, and analyzed metrics related to the plants’ hydraulic system. These samples always had to be collected at dawn, since measurements taken during the day aren’t valid, because the trees are in the process of photosynthesis.

“I had done a lot of fieldwork before, but in places that were easier to access. I would spend a week or two away from home. For this study, we spent months traveling and, since it was a research that collected a lot of data, we had a very large team. Planning all this was very challenging and then there was also the language and culture barrier in Peru and Bolivia,” explains Caroline Signori, who also participated in collecting the samples.

I had done a lot of fieldwork before, but in places that were easier to access. I would spend a week or two away from home. For this study, we spent months traveling and, since it was a research that collected a lot of data, we had a very large team. Planning all this was very challenging and then there was also the language and culture barrier in Peru and Bolivia.

Caroline Signori, researcher and one of the authors

After planning the expedition, the group organized visits during the day to prepare the trees that would be analyzed with ropes and safety equipment. The surveying is conducted in the daylight. Then, at dawn, the climbers used the ropes previously installed to climb up as high as 40 meters. Once up there, they counted on the help of colleagues on the ground to handle a kind of giant scissors, which cut the branch chosen by the scientific team.

During one of these collections, Martin Acosta and one of his fellow climbers encountered an extra challenge on the treetops: “There were a lot of ants up there, and my coworker had to climb down because he couldn’t stand the stings. He couldn’t take it up with the ants biting, so he went down to ensure his safety. But, in the end, he managed to cut the branch and went down, all hurt,” Acosta recalls.

The Burning Season

Assessing the trees’ resistance to drought is important in a scenario of climate change and the advance of deforestation and fires in the Amazon region. But, despite this, the driest season in the biome coincides with the time of year when there are increased records of fire, according to data collected by the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), which coordinates the monitoring program known as BDQueimadas.

This June saw a record number of fires in the Legal Amazon, according to BDQueimadas. The number, 5,731, represents an increase of 15% compared to the same month last year, when 4,978 were detected. Although the study only examines the resistance to drought periods, and not to fire, the two aspects are associated, according to researcher Julia Tavares.

“The study only evaluates the lack of water in the soil, which is caused by drought, and not by fires. But, of course, fires will start more easily when the forest is drier. The importance of our study is that it was the first to assess the vulnerability of the Amazon on a regional scale, that is, the entire Amazon,” Tavares explains.

The researcher also recalls that, due to the characteristics of the trees present in the Amazon, the biome does not have natural fires, like those that occur in other types of vegetation. Because of this, the fires identified by INPE monitoring are always caused by human action.

With the worsening of climate change, however, it is possible that the fires caused will take on greater proportions due to longer-lasting droughts – and many Amazonian trees may no longer be able to withstand either phenomenon.

“Even trees that are naturally more resistant to droughts are suffering greatly because the imbalance of climate change is too much and they can’t take it. This is extremely concerning and it’s something that needs to be taken into account every time the season of droughts and fires occurs,” the researcher says.

Report by InfoAmazonia for the project PlenaMata.