Jair Bolsonaro (PL) says that demarcating 500 Indigenous lands threatens agriculture. A survey done for the project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price) shows that there are 240 demarcation processes in progress, and in most agriculture-producing states, Indigenous land doesn’t cover even 1% of the total land area.

In his first statement after the results of the first round of the 2022 elections, President Jair Bolsonaro (PL) reinforced an argument he’s been repeating since 2017: that in his government “there won’t be a centimeter of land demarcated for Indigenous reserves.” He now adds that the demarcation of Indigenous lands (IL) harms the agriculture business.

“Lula is talking about the demarcation of reserve lands that have been asked for for a while. It’s almost 500 new Indigenous lands. This practically would end agriculture business, we would lose our food security, and our balance of trade would drop,” he said on the night of October 2nd, 2022. The video was published on his YouTube channel and has had 206,000 views. The video was also published on the channel Folha Política, one of the four channels that was demonetized until the end of the election by the Electoral Supreme Court, and has had over 1 million views.

Requested by the project Mentira tem Preço (Lies Have a Price), technicians from the Socio Environmental Institute worked to put the president’s statement to the test. First, Bolsonaro is exaggerating: there aren’t 500 requests for demarcation in the queue. The real number is 240, according to an analysis of the data published by the Diário Oficial da União (Brazilian Federal Register).

Of the 728 demarcation processes formally started by Funai (National Indian Foundation), nearly 67% have already concluded. Bolsonaro’s press secretary did not respond to requests for comment by press time.

How we did the study:

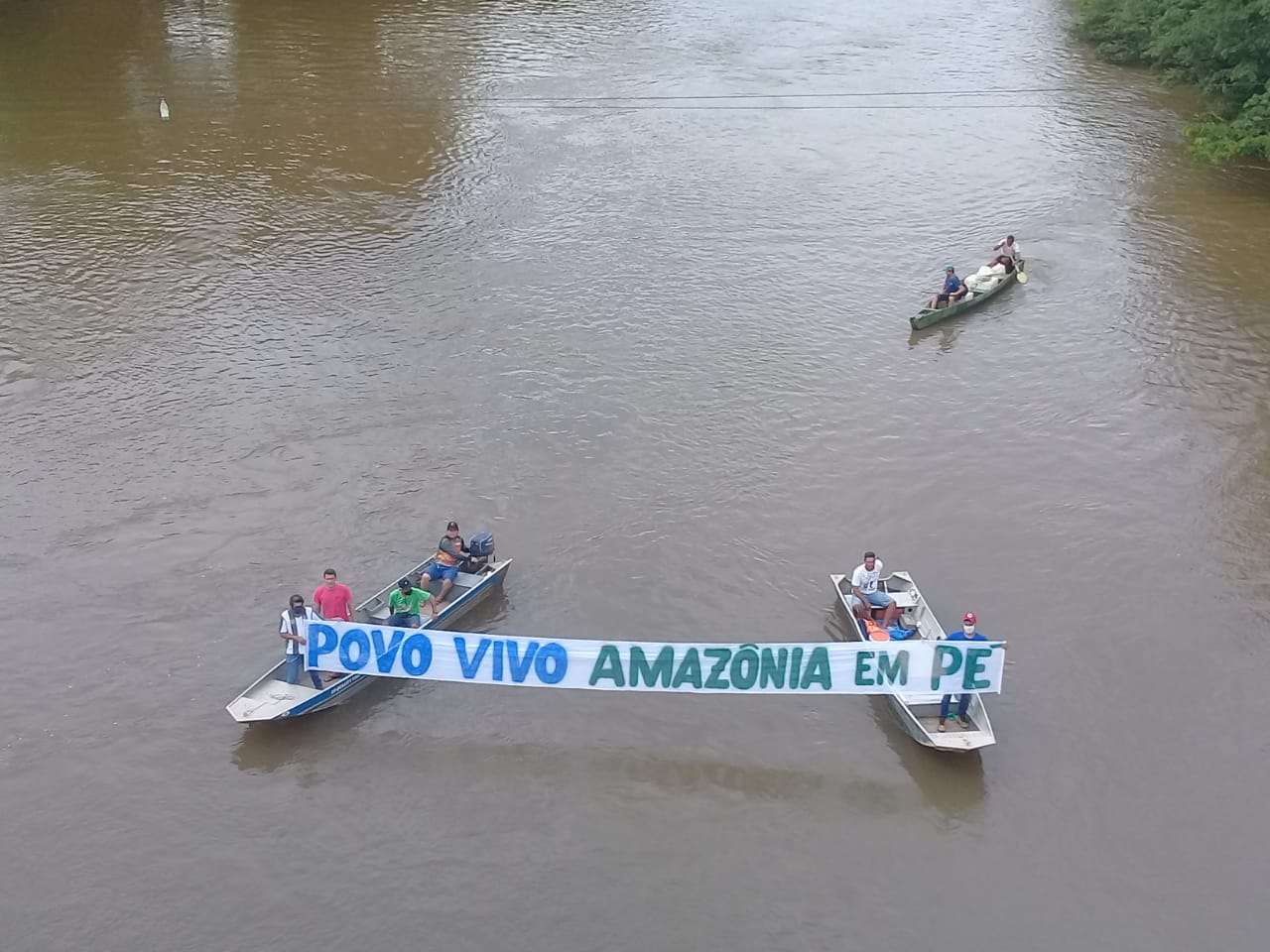

The project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price), initiated in 2021 by InfoAmazonia and the production company FALA, monitors and investigates socio-environmental disinformation. During the 2022 elections, we checked the statements of all the gubernatorial candidates for states in the Legal Amazon region every day during the free televised campaign advertisement slots. We also monitor, through keywords related to social justice and the environment, disinformation about the Amazon on social networks, in public groups on messaging apps, and on platforms.

As for the argument that the demarcation of Indigenous land would curb the advance of the agriculture business, ISA numbers show that of the nine main states where agriculture is a major force, in seven of them the percentage of territory occupied by Indigenous land is less than 1%.

In the state of Mato Grosso, the largest agriculture and cattle producer in Brazil, the percentage of Indigenous land reaches 16% (see table below).

Indigenous Lands occupy about 13.7% of Brazilian territory—a level below the world average of 15%—says Márcio Santilli, a philosopher and founding partner of ISA. In contrast, 41% of Brazilian territory (three times the amount of Indigenous land) is for private usage, according to the 2017 Farming Census conducted by the IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Statistics and Geography). In addition, 20% of the land in the country belongs to just over 51,000 rural proprietors (or 1% of the total), according to the census.

Tereza Cristina, Bolsonaro’s former minister of agriculture, repeatedly said that agribusiness doesn’t need to deforest more to increase production, nor does it need the Amazon to grow. Her statements are confirmed by several studies in the sector, including one from Embrapa (Brazilian Farming Research Company), connected to the federal government. That’s because today nearly 22% of the national territory is used for pastureland—half of that with some extent of degradation—and roughly 8% for agriculture, according to the MapBiomas project and the Brazilian Digital Atlas of Pasturelands.

The absolute majority of Indigenous lands (98%) are within the Legal Amazon region. Currently, 9% of Indigenous lands are awaiting demarcation, counting the ongoing processes with Funai, with preliminarily defined areas and boundaries (and excluding territories “with identification in progress,” “without boundaries” and “without defined areas”).

According to Santilli, today, of all the Indigenous land in the midst of the demarcation process, around two-thirds are in what he considers to be “a bind” from a legal point of view. “But there’s nothing preventing the government from completing the demarcation of the last third,” he says. “What they lack is political effort. All they need is will.”

He explains that there isn’t any data that shows that the demarcation of Indigenous land and agribusiness have a conflict of interests; in fact it is quite the opposite. Some studies show that these lands, because they are protected, contribute both to preserving biodiversity and to fighting climate change that actually harms agriculture.

A study by Ipam (Amazon Environmental Research Institute) shows an example: in northeastern Mato Grosso, the atmospheric temperature reaches from 4ºC to 6ºC higher outside of Indigenous land, because the forest helps regulate the climate. The area around the Xingu Indigenous Land, where the study took place, registers a high rate of deforestation.

This report is part of the project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price)—election special, produced by InfoAmazonia in partnership with the production company Fala. The initiative is part of the Consortium of Civil Society Organizations, Fact checking Agencies and Independent Journalism for the Fight Against Socio-environmental Disinformation. They are also a part of the Initiative the Climate Observatory (Fakebook), the Eco, the Pública, Repórter Brasil and The Facts.

Content is authorized to be republished if published in its entirety. Lies Have a Price is not responsible for alterations to the content by third-parties.