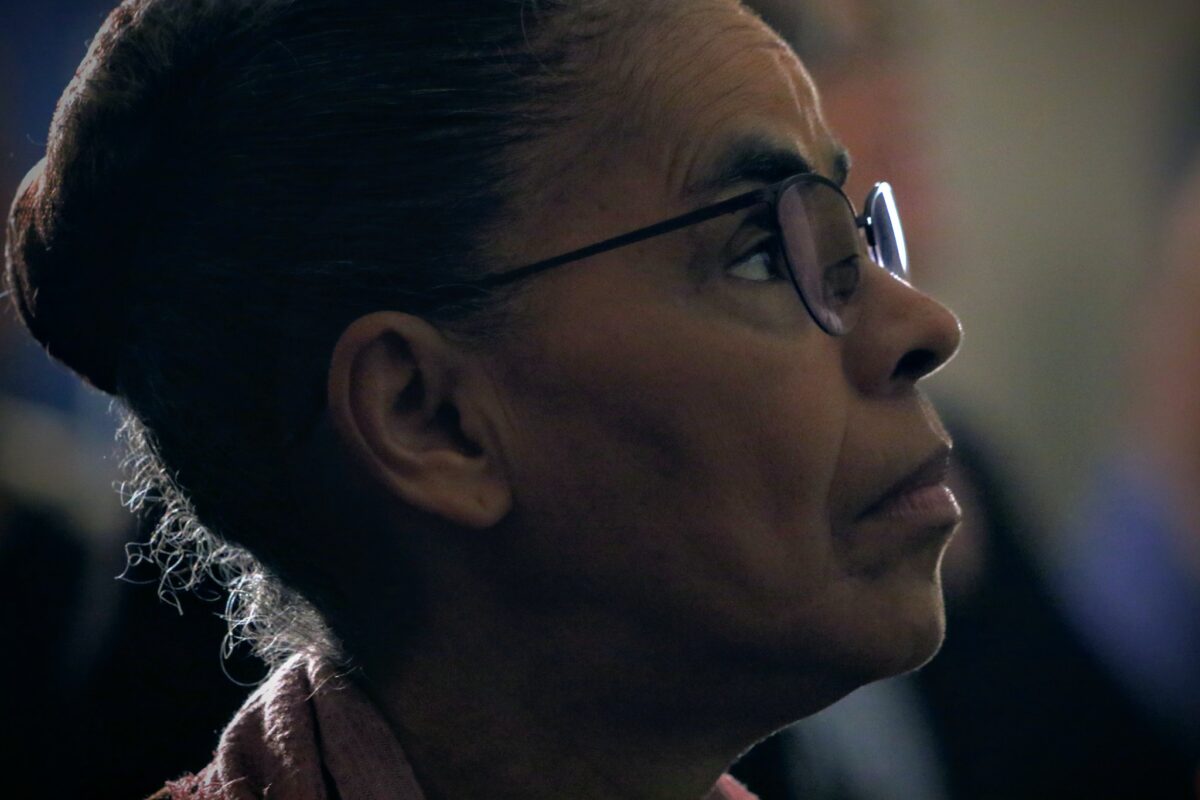

In this interview, the former minister of the Environment and candidate for the Chamber of Deputies responds to the attacks she has suffered from pro-Bolsonaro influencers and speaks about how environmental disinformation works against the environment and discredits science.

Since formally announcing her support for Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT-Worker’s Party), the former minister of the Environment and federal deputy candidate Marina Silva (Rede) has been attacked by pro-Bolsonaro groups on online platforms like YouTube and on messaging apps.

A study done by the project Lies Have a Price (Mentira Tem Preço) shows that influencers and content producers—including one that claims to be a pastor—have produced disinformation to try to dismantle Marina Silva’s political career of over four decades working in defense of the environment and traditional peoples.

Of the analyzed videos, two of them amassed over 400,000 views at the time this article was published. In one of the videos, Silva’s name is associated with large companies and banks. In the other, the former minister is seen as a threat to national sovereignty for wanting to internationalize the Amazon. Neither presents proof or indicates the source of this information.

“Disinformation works at full strength to maintain the current system that highly concentrates wealth, produces enormous social ills, and has huge environmental impacts,” says Marina Silva. In an interview with FALA and InfoAmazonia, the candidate, who is also a historian, professor and environmentalist, explains how environmental disinformation negatively impacts the elections and public policies and puts democracy at risk.

InfoAmazonia: A study by the project Lies Have a Price analyzed videos that accuse you, without proof, of helping to sell the Amazon to foreigners and of a supposed connection between you and business owners and bankers. What is the impact of environmental disinformation on the elections and the formation of public policies?

Marina Silva: The negative impact is huge, primarily in the social dynamic itself, regarding political aspects, projects, views and structures that need to be created and gain support to bring about the transformation from an unsustainable model to a sustainable one, which presupposes prosperity, fighting inequality and strengthening democracy. Disinformation—lies, fake news, denialism—works at full strength to maintain the current system that highly concentrates wealth, produces enormous social ills, and has huge environmental impacts.

Many say that whoever wants to protect the forest and traditional peoples, respecting the Constitution, actually want to sell the Amazon or harm the sovereignty of Brazil. In reality, what we see are those who are handing over the Amazon are the ones who are selling the forest for illegal land possession, illegal mining, illegal logging, illegal fishing, and drug and arms trafficking. They are the ones who are the true threat to the sovereignty that’s out of control. The Amazon today has over 12,000 clandestine airstrips for all types of organized crime, primarily in sensitive regions, as is the case with Vale do Javari [Indigenous Land in the west of the state of Amazonas with at least four isolated Indigenous peoples].

These lies constantly try to make any project unviable—from the point of view of science, politics, or even business-wise—that can compete with or threaten the predatory model of destroying the resources of thousands of years for the profit of a few decades. It’s an enormous loss. Brazilian society is showing, through the electoral process, that it does not want to take the path that the denialists, in conjunction with organized crime, want to impose on this country.

Brazilian society is showing, through the electoral process, that the majority do not want to take the path that the denialists, in conjunction with organized crime, want to impose on this country.

Marina Silva

How we did the study:

The project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price), initiated in 2021 by InfoAmazonia and the production company FALA, monitors and investigates environmental disinformation. During the 2022 elections, we check the speeches of all the gubernatorial candidates for states in the Legal Amazon region every day during the free televised campaign advertisement slots. We also monitor, through keywords related to social justice and the environment, disinformation about the Amazon on social networks, in public groups on messaging apps, and on platforms.

On online platforms, we mapped science denialism, including the data produced by government institutions, such as the National Institute of Space Research (INPE). In this fictitious parallel narrative, Brazil has neither forest fires nor deforestation, in spite of data indicating the extreme opposite. How have we arrived at this time? How does this damage the protection of the forests and traditional communities?

It is a long process of trying to discredit public institutions, public officials, socio-environmental activists, and the scientific community itself. Aligned with the most retrograde economic interests, [these groups] are able to sponser and spread through the social fabric this disinformation and these ways of discrediting and undermining the scientific community. When I was minister of the Environment, Mr. Evaristo de Miranda [Jair Bolsonaro’s environmental policy ideologue], together with the state governments in Rondônia and Mato Grosso, did everything they could to discredit INPE data.

Alongside the Ministry of Science and Technology, we made use of all the ways that we could fight, from the institutional point of view, to undermine them. I reached the point of challenging the state government of Mato Grosso and their supposed technicians by making a site visit, doing an investigation into the information, polygon by polygon, of where there had been deforestation. I had to put myself on the front lines and do this operation, and they weren’t able to undermine the INPE.

The difference is that now the president of the Republic himself, the president of [the Brazilian environmental agency] Ibama, the minister of the Environment, the minister of Science and Technology, they all collaborate with these denialist, lying stances that try to discredit science. They don’t have any commitment to ethics, public decency or truth of any kind. It’s a very tough fight, it brings losses, and penalties are one of them. Ricardo Galvão [the former president of the INPE] was fired because he didn’t agree to cover up information about the deforestation. The teams are weakened, staffed by military personnel who don’t understand the environment, how to monitor it or manage it, much less regulate it and issue fines.

The president of the Republic himself, the president of Ibama, the minister of the environment and the minister of science and technology: they all collaborate with these denialist, lying stances that try to discredit science.

Marina Silva

And for society, what is the legacy of disinformation that leads to a belief in a parallel reality that doesn’t exist?

For society, the damage is tripled. It creates an uninformed public opinion, dealing with lots of false information and lies, with lots of people being manipulated. The other thing is that you weaken every kind of public policy. And the third thing is the fact that we’ve had enormous cuts in the area of science, technology and innovation. Besides the pain of being constantly threatened and harassed within the public agencies, the professionals can’t do their jobs because there are no means to perform their institutional duties, be it a financial issue or even safety for their very lives. The State leaves you to your own fate. This is on top of being fired, as was the case of Representative Alexandre Saraiva [dismissed after testifying against the then-Minister of the Environment Ricardo Salles for permitting illegal possession of lands in the state of Pará] and the director of Environmental Protection at Ibama [Samuel Vieira de Souza was dismissed after heading an operation against illegal mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Land].

Like Bruno Pereira, a fired Funai employee, who was murdered in the Vale do Javari (AM)…

Now this case is something extreme. The absence of the State and the coexistence with crime allowed these criminals to take control and take the lives of good people who are doing what the State should be doing, as is the case of the murderers of Bruno Pereira and [the British journalist] Dom Phillips, to the point that the President [Jair Bolsonaro] himself said that they had “taken a risk.” They said: “Why did they go to a place they shouldn’t have gone? Why did they go mess with whoever’s there?” As if these good people, who respect the law, who defend human rights and the protection of the environment were wrong, as if the criminals should be free to do as they wish, in Bolsonaro’s mind.

The economy that values the forest’s destruction instead of protection is what dominates in the campaigns.

Marina Silva

Plataformas digitais não possuem políticas sobre crise do clima, permitindo que conteúdos relacionados ao negacionismo climático, por exemplo, circulem livremente em um momento que combater a crise do clima é uma agenda mundial. Como a senhora avalia o papel das plataformas digitais e dos investidores das mesmas?

Online platforms do not have policies about the climate crisis, allowing content related to climate denialism, for example, to circulate freely at a time when fighting the climate crisis is on the global agenda. How do you see the role of online platforms and their investors?

Since these platforms have enormous power and reach to circulate content at an unreachable scale, it’s a responsibility that needs to be managed by these platforms, but we also need to find a means of regulation so there is responsibility for the future of the planet, social peace, public health, finding ways to contain the advance of these predatory groups [that attack] democracy, climate balance, public health, and democratic institutions. Obviously this must be a demand from the social fabric that doesn’t want to see the world walking towards the precipice of social, economic, cultural, and civic barbarity.

We also need to find ways, whether through some kind of global regulation or compliant conduct, for these groups, with the view that the national governments are often unable to manage this because [these groups] do not respect borders. Lik groups that can’t operate in the country and seek out “online havens”—I’m coining this term right now—that end up degrading the process of coordinating information from a distance. An example of this is Telegram. This was very clear in the U.S. and here, with the efforts of the Superior Electoral Court [TSE] to contain these lies that were discrediting the electronic voting machines and threats to the democracy in Brazil.

In the project Lies have a Price, we monitor the the free televised campaign advertisements of all the gubernatorial candidates in the nine states of the Legal Amazon region. We have found very little content focused on socio-environmental issues, at a time of record-breaking deforestation and forest fires in the country. Why hasn’t the defense of the Amazon and the environment, traditional communities, and sustainable production become part of the plans for the governors of the Legal Amazon yet?

Unfortunately, the majority of the administrations approach these disputes not to legitimize an alternative to the predatory model, but with “easy” talk about developmentalism. The economy that values the destroyed forest instead of protecting it is what dominates in the campaigns. There are very few who have the courage to make a turn towards another development model. You can see that the governors negotiate, participate in international forums, try to raise money in the name of protecting the Amazon and, in the state of Pará itself, the governor set up a land registration scheme selling a hectare of the forest to be registered for around R$ 40. This is an absurdity. The governors do indeed have mechanisms to also make plans to prevent and control deforestation. When I was the minister of the Environment, in addition to the plan to control deforestation, we made a plan for sustainable development of the Amazon and one of the traditional populations. The next step was to involve the states so that they would also have plans for combating deforestation and sustainable development. Unfortunately, I left the government a few days after the plans were ready. The one who took over the plans was the philosopher and social theorist [Roberto] Mangabeira Unger, who did absolutely nothing to move them ahead. Everything he did, together with the governors of the Amazon, was to put pressure on a land registration scheme in 2009, which regularized 47 million hectares of land with falsified deeds.

No longer can land theft be rewarded by government after government with land regularization, turning those who stole public lands into landowners.

Marina Silva

The State of Amazonas has record-breaking fires, yet no candidate has presented a proposal to fight them. In Pará, mining is the “vocation,” but billions in resources have not changed the life of the population in cities that have mined the most. In Acre, “florestania”—responsible forestry—has become linked to poverty, when statistics show just the opposite. How do you evaluate this situation in the Legal Amazon region? Is there a way out?

There is a way out. In a democracy, this exit is always grounded in democracy. Now, whoever has the opportunity to democratically take charge of a government has to have a commitment to change this reality so that we start to profit from a flourishing forest, by respecting a diversified economy in the Amazon that’s compatible with the protection of its biodiversity and Indigenous peoples.

No longer can land theft be rewarded by government after government with land regularization, turning those who stole public lands into landowners. No longer can the Safra Fund, now at R$ 340 billion, dedicate only 1% of these resources for low-carbon agriculture and the rest for conventional agriculture. It’s necessary for this resource to be the basis for a transition and that there be a set of goals to be reached to reclaim new investments.

Another aspect is to create an entire infrastructure based on sustainable development: consolidating areas that can be used for agriculture but also a place for the Indigenous, quilombola and extractivist populations. The goal for Brazil is to reforest roughly 12 million hectares of land. This has the potential to create 2 million jobs.

So yes, there is a way out. Now, these ways need whoever is in the government to do what is necessary, what I call long-term politics, to institutionalize this benefit for whoever comes next. Public policies need to be institutionalized, and what can be made law must become law to avoid everything being dismantled by whoever comes next, like Bolsonaro has done.

This report is part of the project Lies Have a Price (Mentira Tem Preço)—election special, produced by InfoAmazonia in partnership with the production company Fala. The initiative is part of the Consortium of Civil Society Organizations, Factchecking Agencies and Independent Journalism for the Fight Against Socio-environmental Disinformation. They are also a part of the Initiative the Climate Observatory (Fakebook), the Eco, the Pública, Repórter Brasil and The Facts.

Content is authorized to be republished if published in its entirety. Lies Have a Price is not responsible for alterations to the content by third-parties.