In the Munduruku indigenous community’s mythology, the Tapajós River was created by the deity Karosakaybu, from the tucumã (a Brazilian palm tree) milk, as a kind of paradise. In the basin of what is one of the largest bodies of water in the Brazilian Amazon, Karosakaybu created the Munduruku and, to ensure food for the people, transformed indigenous people into animals.

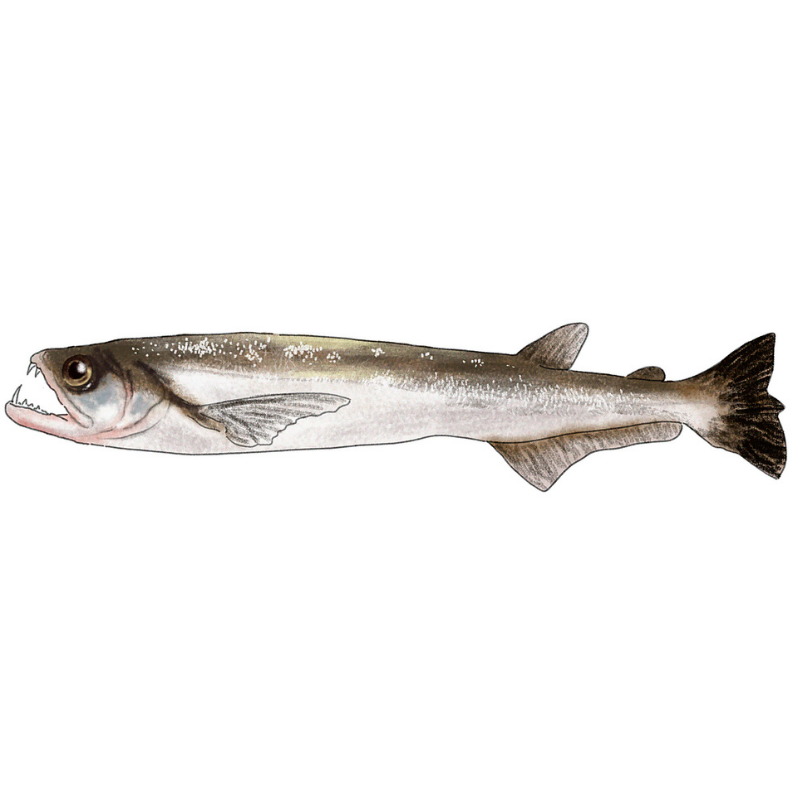

According to tradition, the matrinxã, a kind of fish abundant in the region, was transformed from Munduruku women. That’s why, nowadays, this fish is exclusively caught once a year, for a traditional festival that usually takes place every September. On this special occasion, fishermen use a poisonous plant to agitate the fish and catch them. For weeks, the indigenous community only eats matrinxã.

“We have fun with the fish. The kids play in the village and the fish play in the water”, compares Juarez Saw Munduruku, chief of the Sawré Muybu indigenous community in Pará state. “The matrinxã was made of people, it was transformed from Munduruku people. That’s why this fish is not like the others,” he explains.

Fishing is traditionally the main local livelihood, but in recent years, the consumption of fish has generated concern among the population due to the high concentrations of mercury found in some species. The matrinxã is not among the most contaminated, but among other types, the level is alarming.

In November 2021, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) published a study that revealed that all the residents in three villages in the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Land had mercury in their bodies. According to the study, 60 percent of them had levels of the toxic metal in their blood above the limit considered safe by the World Health Organization (WHO).

According to the WHO, mercury contamination highly affects the human nervous system. When exposed to the metal during pregnancy, fetuses are susceptible to developing neurological symptoms in early childhood, such as cognitive delay, difficulty in attention, and delay in motor and language development. Among young people and adults, it affects motor coordination and may cause loss of hearing and sensitivity in the limbs, in addition to headaches and sleep disturbances.

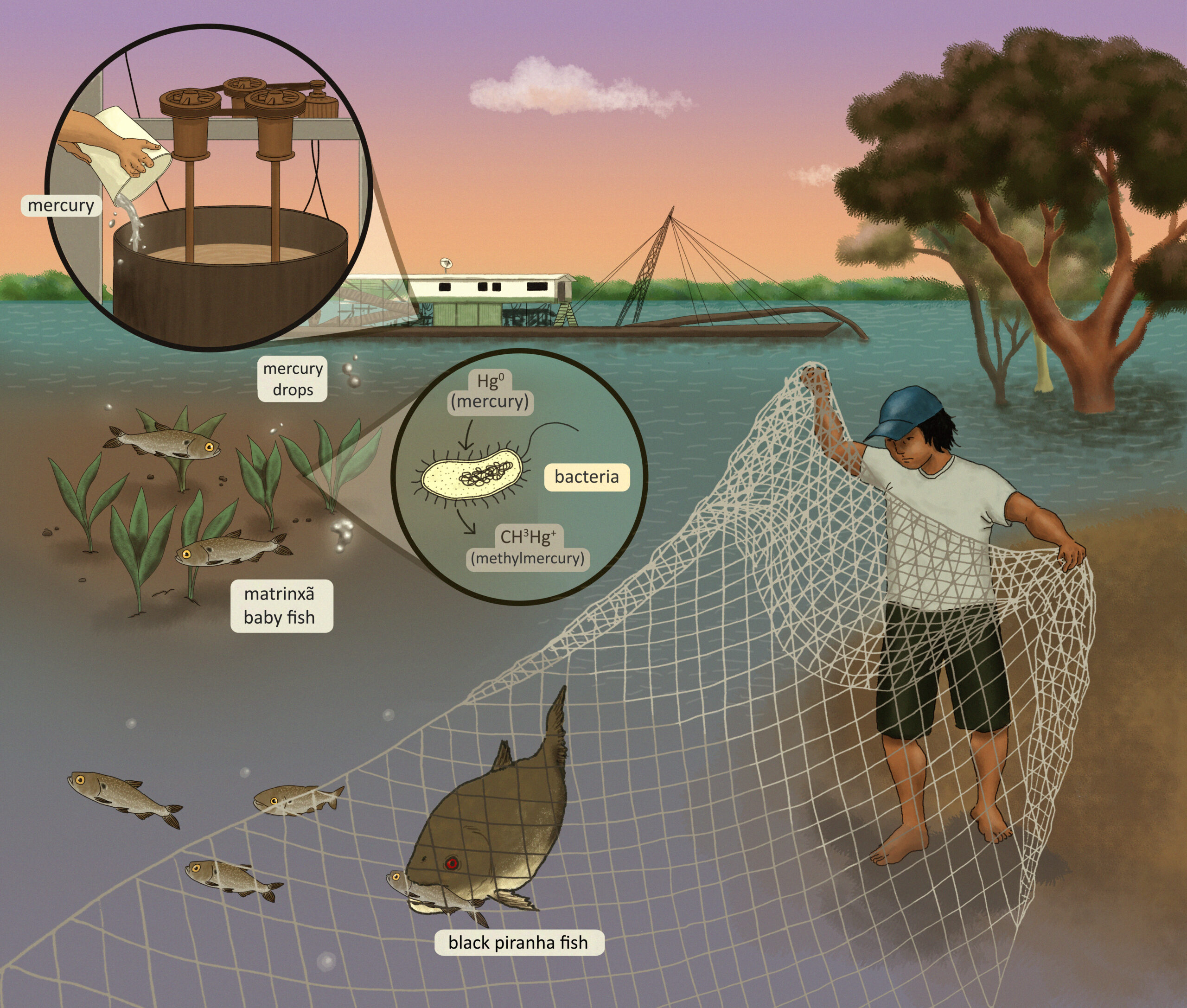

The cycle of mercury contamination

The main source of contamination for the Munduruku is the consumption of fish from the Tapajós River tainted by mercury from wildcat mining. Since the 1950s, the Tapajós region has been one of the main mining regions of Brazil. In recent years, the activity has been boosted by the Bolsonaro government’s repeated attempts to relax mining legislation in protected areas in the country.

To understand how the mercury used by miners contaminates fish and humans who eat them, InfoAmazonia visited the Sawré Muybu indigenous community and interviewed experts.

In mining, Mercury is used in its metallic form to separate tiny grains of gold from other sediments. When melted, Mercury has the ability to bond with other metals and form amalgams. When these amalgams are burned, the mercury evaporates, resulting in pure gold.

Through this process, gaseous mercury is released into the atmosphere, and part of liquid mercury ends up being dumped into the environment. Once in the water, the metal tends to be trapped in the organic matter of the river, being absorbed by the particles and deposited in the river bed.

It is at the bottom of rivers that mercury is transformed by bacteria into its organic form, methylmercury. This form, according to Ana Claudia Santiago de Vasconcellos, a researcher in public health at the Polytechnic School of Health Joaquim Venâncio da Fiocruz, is the “most dangerous for human health.”

From then on, the methylmercury starts to be absorbed by the food chain. Microalgae, fish larvae, and insects, as well as other aquatic animals such as shrimp and crabs, tend to be the first consumers. These smaller organisms serve as food for larger animals and the methylmercury is “bioaccumulating and biomagnifying” along the chain. In other words, its concentration is highest in animals at the top of the food chain.

According to the researcher, larger and carnivorous fish have higher concentrations of methylmercury than the fish that are at the bottom of the food chain, which are the herbivores, feeding on seeds, fruits, and leaves. For this reason, she advises communities along the Tapajós River to avoid consuming carnivorous fish.

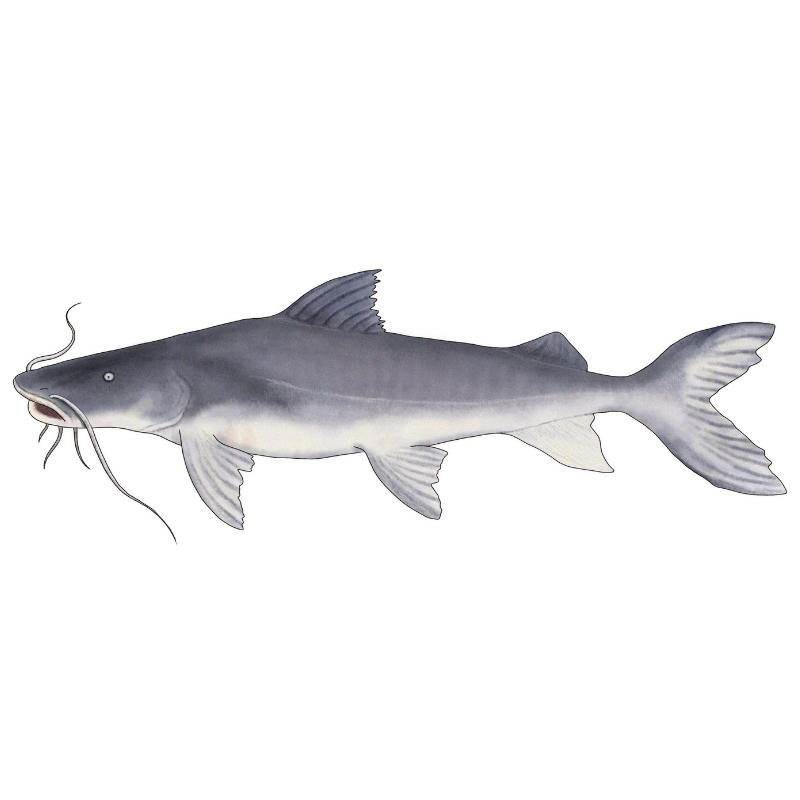

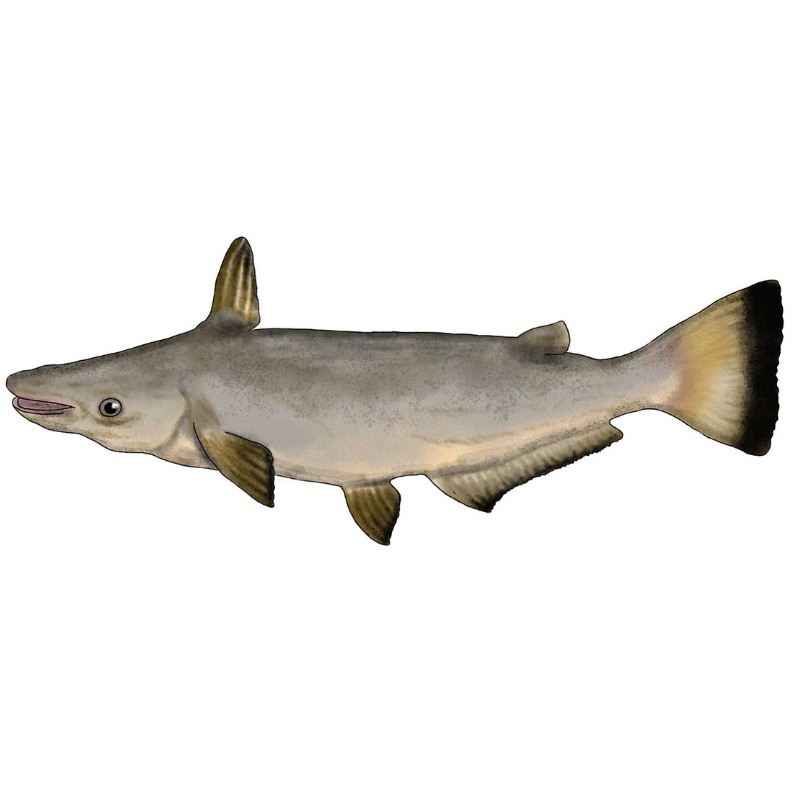

Among the carnivorous fish most consumed by the Munduruku are the black piranha, the peacock bass, and the “calf”, the name given to the young of the piraíba species.

Given the high levels of mercury concentration among the Munduruku who participated in the Fiocruz research, Vasconcellos is developing a textbook project to explain the contamination cycle. The book is being translated into Munduruku by Honésio Dacê Munduruku, who represents teachers from Medium Tapajós in Indigenous Education Schools. He says the translation is difficult because the content is full of technical and scientific expressions that do not exist in the indigenous language. The words mercury, mining, and gold, for example, do not exist in Munduruku.

According to the teacher, his relatives were surprised by the result of the Fiocruz research. “We didn’t know, we were scared”. Carnivorous species are among his family’s favorite fish.

A challenging change of habits

The first time that chief Juarez Saw Munduruku heard about mercury contamination was when his friend Cássio Beda fell ill.

Beda, an environmental activist who was a member of the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi) and helped the population of Sawré Muybu in the self-demarcation of the territory, was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). The degenerative disease progressed rapidly after 2017. He passed away on April 4, 2021. During his last years, he learned the disease could be related to mercury contamination. In a video he recorded in 2018, he said his symptoms were similar to those of Minamata disease, a neurological syndrome caused by mercury poisoning.

The disease’s name refers to the mass contamination of residents of the Japanese city of Minamata, where, between 1932 and 1968, more than 5,000 people were seriously contaminated with mercury waste discarded by an industry owned by the Chisso Corporation. The disaster, which killed around 700 people, led to the Minamata Convention, enacted in 2018. The environmental treaty, to which Brazil is a signatory, aims to protect human health and the environment from adverse effects of the toxic metal.

It was after Beda got sick that the community requested the mercury levels to be tested. After receiving the results, the chief is concerned about the next steps. “We need to adapt, but if we don’t find other kinds of fish, we have to eat what we get”, he says.

We need to adapt, but if we don’t find other kinds of fish, we have to eat what we get

Juarez Saw, Cacique Munduruku

Fish are the Munduruku’s main source of protein. The chief’s biggest worry is the future. “This generation of children cannot continue to eat contaminated fish.”

During the rainy season, according to Juarez, it is hard to select which fish to consume. As the fish swim deeper into flooded rivers, they become harder to catch. In the dry season, with the fish concentrated in the shallows, the indigenous people fish with nets left for hours between the trees. “In the summer, you can even choose the fish you want”, explains the chief, saying it is easier to select herbivorous fish.

Carnivorous fish

Since the local communities learned about mercury contamination, they have discussed how to change their eating habits. InfoAmazonia visited several families in Sawré Muybu Indigenous village and heard how difficult it has been for them to change their fish-eating habits. Nurse technician Luciene Saw Munduruku has worked since 2020 visiting indigenous communities in the region. She learned that for some Munduruku families the advice to eat herbivorous fish is even more challenging since their villages are far away from the city and the families do not have money to buy food in the markets. “They are hungry, they say fish is their only food and they cannot avoid eating it.”

A silent and multifaceted poisoning

Anemia and low weight, especially among children, are some of the common health problems observed in the region. “All the villages we visit have underweight children”, explains Luciene.

Neurologist Erik Jennings, who works with indigenous health in the region, has become a reference in the identification and treatment of toxic metal contamination. The neurologist highlights that there is a direct relationship between mercury intoxication and anemic condition, through the impact of the metal on the metabolic systems of the human organism. However, the doctor also points to an indirect relationship. “When mercury levels are high, it’s the tip of the iceberg. Underneath that there is a serious social, environmental, cultural, and economic change that affects food security and the well-being of that population”, he says.

The Munduruku community has discussed building artisan wells as an alternative to facilitate water consumption and fish farming ponds. Indigenous teacher Jairo Saw Munduruku is one of the project managers and has been asking Sesai to carry it out. “We need fish that do not have contact with the river, that are healthy. Perhaps fish farming is the only alternative”, he thinks.

Jairo lives in the Sawré Aboy community, close to Jamanxim river, a tributary of the Tapajós river. In January 2022, when a change of color of the Tapajos waters came to attention, a study by Mapbiomas NGO analyzed satellite and flyover images along the river and identified Jamanxim as one of the biggest deposits of gold mining sediments.

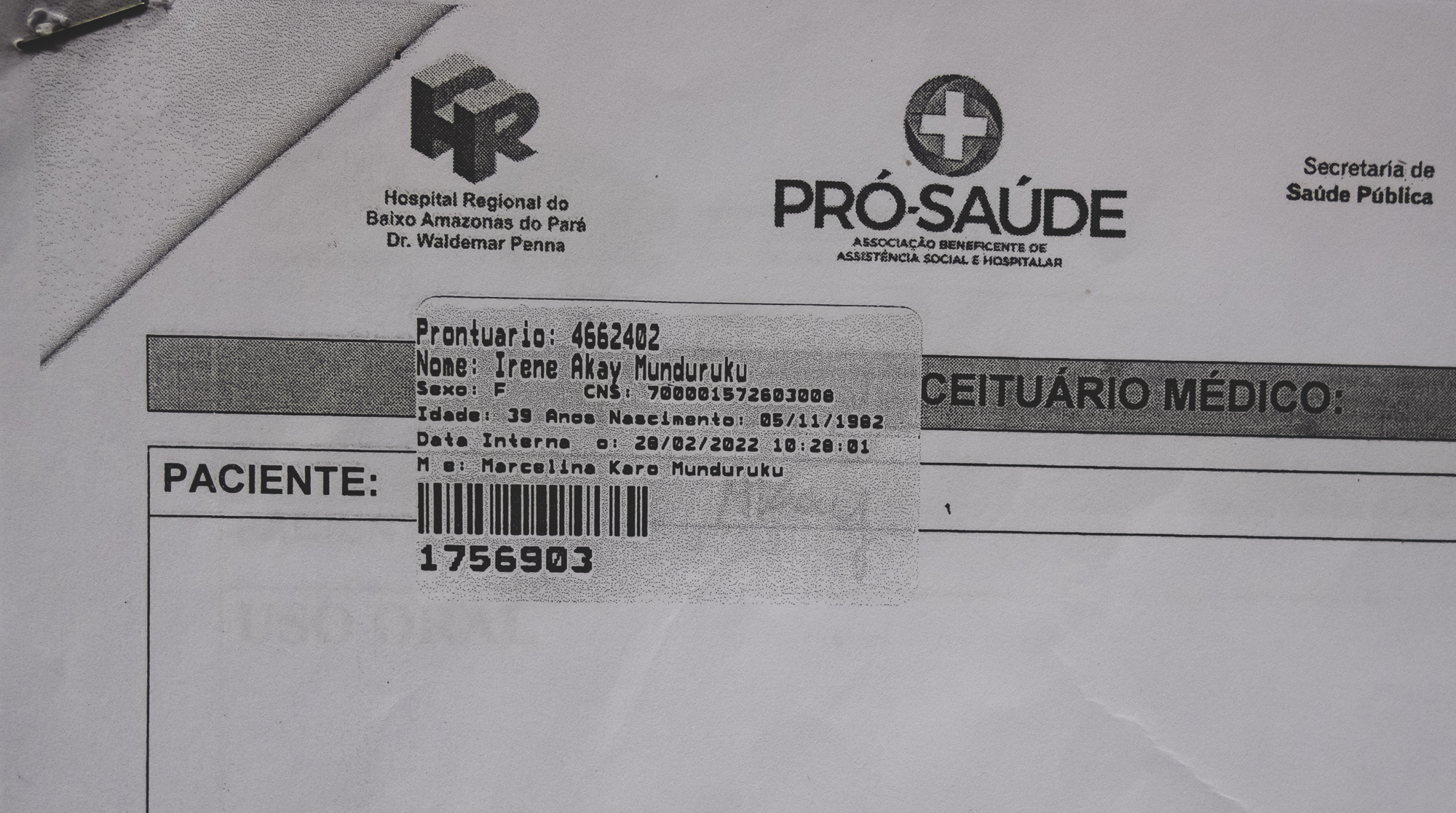

On April 5, Jairo lost his wife, Irene Akay Munduruku. A leader of women, Irene was 39 years old and died at Santarém regional hospital, where she was treating cancer that started in her liver and one of her lungs.

Sawré Aboy has the highest percentage of people with severe mercury contamination according to Fiocruz’s research: 87,5 percent of participants living there were contaminated. According to Jairo, Irene had one of the highest levels. The study revealed that the highest level of mercury found among adult women was 20.2 µg/g. The safe limit set by the World Health Organization for mercury is 10 μg/L (micrograms per liter).

According to doctor Erik Jennings, who participated in Irene’s treatment, there’s no proof that her cancer was caused by mercury contamination. “Any neoplasm (tumor) is a consequence of an inflammatory or chemical pressure. It can be from tobacco, pesticides, or mercury. It causes chemical stress on the cells. So we can’t say it was from mercury, but we cannot discard it either,” he explains.

Besides cancer, Jairo says his wife was suffering from atrophy in one of her fingers, a symptom he believes is related to mercury.

Jairo recalls his wife’s dream was to create a community full of trees for the family, including her mom, her five children, and three grandchildren. “She had a sense of community,” he says. The couple fought together for many years against mining activities in indigenous communities. “I miss her a lot. But I have to be strong, honor her legacy and keep fighting,” he says.

The liver is one of the most affected organs in the process of mercury metabolization process, so liver markers are usually altered in cases of contamination. However, according to Jennings, the most common symptoms of contamination that can be observed among the adult Munduruku population is neurological. Altered attention, reduced ability to concentrate, and complaints of numbness in the hands and feet, are among them. Health professionals have also noted cases of children born with mental and physical malformations and that the community has a higher average of wheelchairs than other indigenous communities.

Prenatal risks

The consequences of mercury contamination among pregnant women are one of the biggest concerns of health professionals and scientists researching the topic. This is because exposure to mercury in the prenatal period poses a serious risk of damaging the fetal central nervous system. Methylmercury can cross the placental barrier, affecting the formation of the fetus in the first weeks of gestation.

In these cases, spontaneous abortion is a common response of the pregnant woman’s body. When pregnancy continues, children may be born with malformations or cognitive ability loss and delay in psychomotor and mental development, in addition to having the immune system impacted.

Doctor Paulo Cesar Basta, one of the authors of the Fiocruz study, points out that in the areas impacted by mining in the Amazon, the population suffers from “permanent exposure”.

“People have been exposed forever and ever. Mercury passes through the pregnant woman’s bloodstream and reaches the child, so if the pregnant woman is eating contaminated fish, the child is being contaminated. Afterward, this child receives mercury through breast milk. Then it grows and continues to eat contaminated fish”, he lists.

While visiting the Sawré Muybu community, InfoAmazonia spoke with three young mothers that lost their children in the past two years.

Mercury passes through the pregnant woman’s bloodstream and reaches the child, so if the pregnant woman is eating contaminated fish, the child is being contaminated.

Paulo Cesar Basta, doctor

Ciane Paigõ Munduruku’s daughter, Jay’Um, an 11-month-old baby, died in 2020. “She was very sick and I didn’t know what it was”, says Ciene, who is 23 years old. Weakness in the legs, diarrhea, and fever were some of the symptoms that affected the baby. The mother says her daughter even had her hair collected for the Fiocruz exam and, after her death, she claims to have been informed by the chief that the child’s mercury levels were significantly high. “They said the mercury had taken hold of her.”

They said the mercury had taken hold of her.

Ciene Paigõ Munduruku, about your daughter that died in 2020

Because of the pandemic, Fiocruz researchers were unable to deliver the results directly to the indigenous people in the village. The data were passed on to health agents and generally reported to the chiefs of Sawré Muybu.

Ciene says that she ate fish throughout her daughter’s pregnancy. “We don’t have anything else to eat,” she says.

After Jau’Um’s death, Ciene had another daughter and says she tried not to eat carnivorous fish during her pregnancy. Out of fear, the indigenous woman reveals that she is avoiding getting pregnant. The fear is shared by other Munduruku women interviewed by InfoAmazonia.

Translated by Letícia Duarte

This story was produced in partnership with the documentary “Amazônia, a Nova Minamata?” (The Amazon, A New Minamata?), by Jorge Bodanzky, with support from Ocean Films, Films4Transparency (F4T) and Journalists 4 Transparency (J4T).

It also has the support of Report for the World, a The GroundTruth Project initiative.