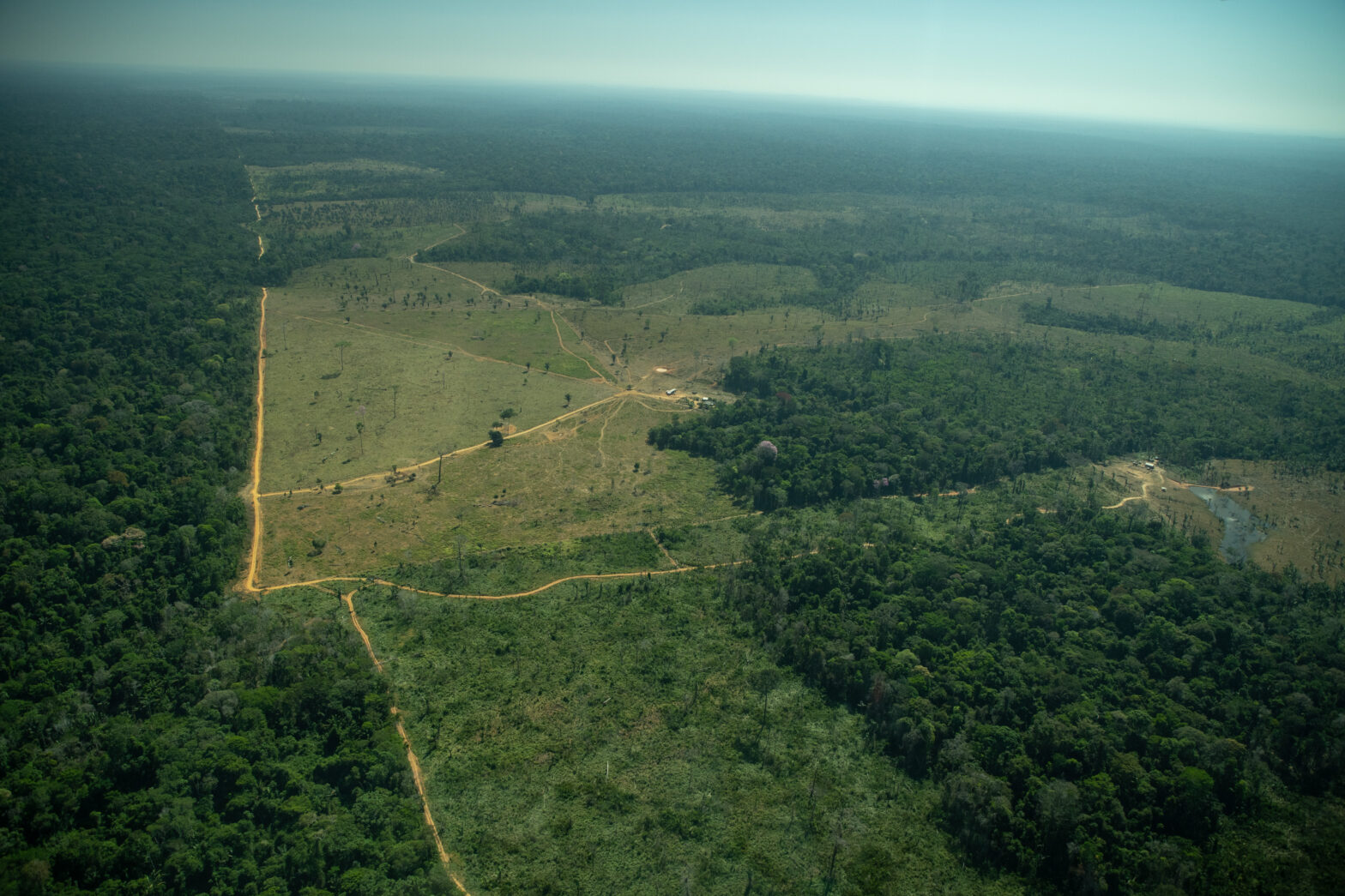

The measure can expand forest losses by at least 100,000 km² in the state, according to an analysis by the Forest Code Observatory, and harm socio-environmental and economic agendas throughout the country.

A bill that wants to remove Mato Grosso from the limits of the Legal Amazon is generating a strong backlash among researchers, environmentalists, and NGOs. Bill 337, proposed in February this year by Congressman Juarez Costa (MDB-MT), amends forestry legislation, justifying that the rules are very strict and restrict rural production.

The text received support from farmers and the governor Mauro Mendes, a member of União Brasil, a political party created from the merger between the Liberal Social Party (PSL) and Democrats (DEM). Mendes defends the measure but wants to maintain a 75% income tax exemption for companies installed in the Legal Amazon, granted by the Superintendence for Development of the Amazon (Sudam). Claims for the state to be withdrawn from the Legal Amazon have come since the mid-2000s, but they have only picked up momentum now.

The proposal will increase deforestation in the state, an agribusiness leader, by at least 100,000 km², according to estimates by the Forest Code Observatory, a collective comprised of 36 civil entities that has been monitoring the implementation of forest legislation since 2013. Since 1988, when Prodes/Inpe began their satellite monitoring programs, Mato Grosso has been the second most deforested state in the Amazon. In the region, laws require that 80% of a rural property’s area must keep native vegetation – the percentage drops to 35% in properties in hybrid forest and Cerrado regions.

In an attempt to stop the bill, researchers, non-governmental organizations, politicians, and citizens gather signatures for a manifesto.

To understand the game of political pressures inside and outside Parliament and the effects the measure would have, we talked to lawyer Roberta Giudice, executive secretary of the Forest Code Observatory. Check out the interview’s main excerpts below:

InfoAmazonia – What will be the impacts of Mato Grosso being excluded from the Legal Amazon?

Roberta Giudice – We have had similar political proposals from Amazonian states since the mid-2000s. Mato Grosso’s demand to leave the Legal Amazon has no other motivation than to increase deforestation, forgive illegal deforestation, and reduce the need for forest restoration.

This bill will have terrible impacts if it is approved, such as the possibility of the deforestation of at least another 100,000 km² – an area the size of the state of Pernambuco. This would occur with the reduction of Legal Reserves (RLs) throughout the state, from 80% to 20% in rainforest areas, and 35% to 20% in the Cerrado.

The measure may lead to further restrictions to access markets such as the United States and the European Union, which are organized to no longer buy products linked to any type of deforestation. This can simply block exports of Brazilian commodities

Roberta Giudice, executive secretary of the Forest Code Observatory

The new losses would equal another 67% of the 150,000 km² already deforested in Mato Grosso since 1988. This would bring harm to both urban and rural areas by reducing environmental services, such as maintaining the quantity and quality of water, generating moisture for the formation of rainfall, and maintaining pollinators for crops.

Additionally, the measure may lead to further restrictions to access markets such as the United States and the European Union, which are organized to no longer buy products linked to any type of deforestation. This can simply block exports of Brazilian commodities, and there is no point in arguing that these are trade barriers. These are decisions of nations aligned with scenarios of climate change, biodiversity loss, and other agendas that we can no longer postpone.

Does it make sense to reduce Legal Reserves when analyses show that only 23% of the 389 thousand properties in the Amazon need to maintain 80% of their lands with standing forests?

The Legal Reserve of 80% in the Amazon was established in 1996, after a record year of deforestation with 29,000 km² felled in the Amazon. Until then, properties had to preserve 50% of their territory, according to the 1965 Forest Code. The survey shows that, in Mato Grosso, only 469 properties will reduce their Legal Reserves from 80% to 20%, and 2,134 from 50% to 20%, as they have already benefited from other legal provisions that reduce the need to maintain these protected areas. In a country with a population of over 200 million, it is a small number of individuals who would benefit from changes in Brazil’s forestry legislation.

Are Legal Reserves and Permanent Preservation Areas exclusive to Brazil and do they harm private property rights, as defended by the Agribusiness (Ruralista) Bench and its supporters in the Legislative and Executive?

Brazil is still one of the countries with the richest forests, among other types of native vegetation. At the same time, other nations, such as some in the European Union, have been recovering their vegetation, which had been deforested centuries ago. Many have instruments similar to our Legal Reserves (RLs) and Permanent Preservation Areas (APPs).

Our forestry legislation dates back to the 1930s and was initially inspired by European legislation, but it is not possible to simply compare parameters for the protection and recovery of native vegetation between countries with such different historical, social, and cultural realities. Furthermore, the Brazilian constitution mandates the maintenance and restoration of natural environments and ensures the social role of rural properties. The right of ownership is limited by other collective rights. Just as there are rules for a dentist to open and run an office, there are parameters for production in the field.

How does Mato Grosso agribusiness, especially companies focused on exports, tolerate so much destruction?

Large to small Brazilian farmers have witnessed growing counter-reactions to production models associated with deforestation and other socio-environmental impacts. But some sectors and parliamentarians still prefer to maintain a polarization between producing and conserving. It is necessary to identify their sources of funding and the short-term interests behind them. Defending this agenda also damages the country’s image at the international level.

Aren’t initiatives to reduce the impacts of agriculture in Mato Grosso incompatible with demands to leave the Legal Amazon?

The Produce, Conserve, Include (PCI) Initiative, for instance, was created precisely to attract resources and create an agenda of actions to cut greenhouse gas emissions, limit deforestation, improve livestock efficiency, and recover native vegetation. But the program loses all meaning in the face of the demand for Mato Grosso to be removed from the Legal Amazon, which is supported by the state government,

An analysis shows that, over 11 years, 92% of deforestation on soybean farms in Mato Grosso was illegal. Does forestry legislation not provide the means to identify those responsible for the crimes?

Yes, it does, with the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR). The Federal Prosecutor’s Office needs to act further based on these data, which allow us to know who is responsible for illegal and authorized deforestation. The information could be used more extensively in monitoring and inspection. Without this, the government continues to enable impunity, stimulating more deforestation. I’m not saying that fines are the only instrument to curtail illicit acts. Conduct adjustment contracts, environmental education, and other instruments are a great fit for certain audiences.

The New Forest Code (Law 12.651) turns 10 years old in May. What are the main advances and gaps in its implementation?

Implementation could have been sped up, especially by states that have not yet validated environmental registrations or have not regulated their Environmental Compliance Programs (PRAs), which are fundamental to the restoration of native vegetation. At the same time, we have never had such a large amount of information on land use and occupation in the country. Judicial arguments against the law were settled by the Supreme Court (STF). Now, we need to enforce it as it is, allowing no setbacks. We need to reinforce that the law can and should come off the ground, benefiting both environmental and productive sectors.

Are there any economic incentives to strengthen the law’s enforcement?

The BNDES, for example, already has a credit line for ecological restoration and forest economy. But I believe that these instruments will eventually be demanded by the producers themselves, given the need to recover native vegetation areas and other obligations set by the forest legislation. This will be critical to ensure that deforested APPs (Permanent Protection Areas) are recovered by 2032, as required by law.

Almost 60 proposals are being discussed in the National Congress amending the forestry legislation of 2012. Haven’t the agendas of agribusiness and other sectors already been taken into account?

Some sectors have not yet realized that it is necessary and inevitable to produce while conserving environments and services, that there are limitations to land use. Nor do they pay attention to a day-to-day increasingly punctuated by water scarcity, extreme heat, crop failures, and floods, such as those that affected Southeast Brazil this year.

Tragedies like these show that we need more urban PPAs, and not just to sell their use to the highest bidder, as approved by the National Congress. We cannot give in to an immediate economic or electoral vision, which does not take into account the protection of the environment as a guarantor of a safer future for society as a whole.

The feeling is that we are facing a “closing sale”, where they’re trying to approve as many setbacks as possible before the end of the year

Roberta Giudice, executive secretary of the Forest Code Observatory

What are your expectations for forestry legislation in this election year (2022)?

There are several very negative bills under discussion, while positive proposals do not move forward. Projects in the Chamber and the Senate can delay the regulation and execution of PRAs (Environmental Compliance Programs), change the time frame for the recovery of deforested areas, and expand amnesties to environmental crimes, among others. I have watched with great concern as bills with setbacks are being passed and signed into law. The feeling is that we are facing a “closing sale”, where they’re trying to approve as many setbacks as possible before the end of the year. Furthermore, they are doing this through less democratic processes, trampling on debates in commissions or imposing emergency regimes to consider bills, as they did with the bill that opens indigenous lands to mining and other economic activities.

InfoAmazonia’s report for PlenaMata project.