Editor´s note: A series of murders, threats and persecutions have affected the daily life of Cedro and Flexeira, two communities in Maranhão state, in the northeast of Brazil. Both are quilombola communities, which are formed by the descendants of Afrobrazilian who fled slavery between the 16th century and 1888, when slavery was abolished in the country.

More than a century later, quilombolas are still a symbol of resistance. There are 3,475 quilombola communities in the country, most of them in the Northeast region, according to data from the Brazilian government.

A judge, a prosecutor and a substitute city council member are directly involved in land conflicts targeting Cedro e Flexeira territories in the past two years, highlighting how these communities have been neglected by a government that keeps failing in protecting their basic rights.

In recent years, quilombola leader Laudivino Diniz has rarely left home. Two reasons on top of the pandemic explain his isolation: Laudivino has been under house arrest since November 2019, when he and four relatives were arrested for ripping out electric fences placed by buffalo herders on the lands of the Flexeira quilombola community in the state of Maranhão. He is also afraid that if he steps out, he’ll be killed, as it has become the norm in his community, where murders, death threats and persecution are frequent.

Flexeira is located in Arari city, which in 2020 was among the top in the national ranking of murders in the context of rural conflicts, according to data from the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT). In the past two years, five quilombolas have been murdered in Arari. Two of them were residents of the Flexeira community and three of the neighboring community of Cedro. All the victims were members of the Forums and Citizenship Networks, a social movement advocating for the rights of traditional communities in Maranhão state, and were fighting against the fencing of the wild fields in the region.

Killed in the land conflict

José Francisco Lopes Rodrigues, known as “Quiqui”, a resident of Cedro community, was murdered at home. He went to the hospital before dying, in January 2022.

João de Deus Moreira Rodrigues was killed by two gunmen on a motorcycle on the night of October 29, 2021, while sitting outdoors in the Flexeira Community.

Antônio Gonçalo Diniz was shot dead by two men on July 2, 2021, while washing his motorcycle in front of his home in the Flexeira community.

Juscelino Fernandes Diniz and Wanderson de Jesus Rodrigues Fernandes, father and son, were killed on January 5, 2020 in Cedro community. Diniz’s wife, children and grandson witnessed the killing.

The most recent victim was José Francisco Lopes Rodrigues, a resident of Cedro, known as Quiqui. After being shot by a sniper who was hiding in his residence. Quiqui was hospitalized for five days in Maranhão state capital, São Luís, before dying on January 8.

Although the shooter has not been identified and the police investigation does not name any suspects, community leaders, family members and neighbors of Quiqui claim that his murder, as well as the murder of the other four quilombolas, were directly related to a years-long conflict between their communities and local farmers identified as land grabbers.

We don’t want more land than what we already have, but have a voice and be heard.

Laudivino Diniz, quilombola leader

Public figures in Maranhão state are among those involved in the region’s land conflict. Judge Angela Maria Moraes Salazar and her husband, state attorney Carlos Santana Lopes, for example, raise buffaloes on a property that occupies about 100 hectares of land claimed by the quilombolas. In addition to being a judge, Salazar is a State Electoral Court inspector. The influential couple is the author of a series of lawsuits against members of the communities. Among them was Juscelino Fernandes Diniz, a quilombola leader who was assassinated in early 2020 in Arari city.

After Quiqui’s murder, the CPT released a note denouncing the state of violence, criminalization of social movements, leaders assassinations and attacks on human rights activists in the region: “In 2021 alone, nine people were killed in conflicts over land in the state, according to data from National CPT. This number places Maranhão as the state with the highest number of murders last year.”

“Illegal appropriation” and land grabbing

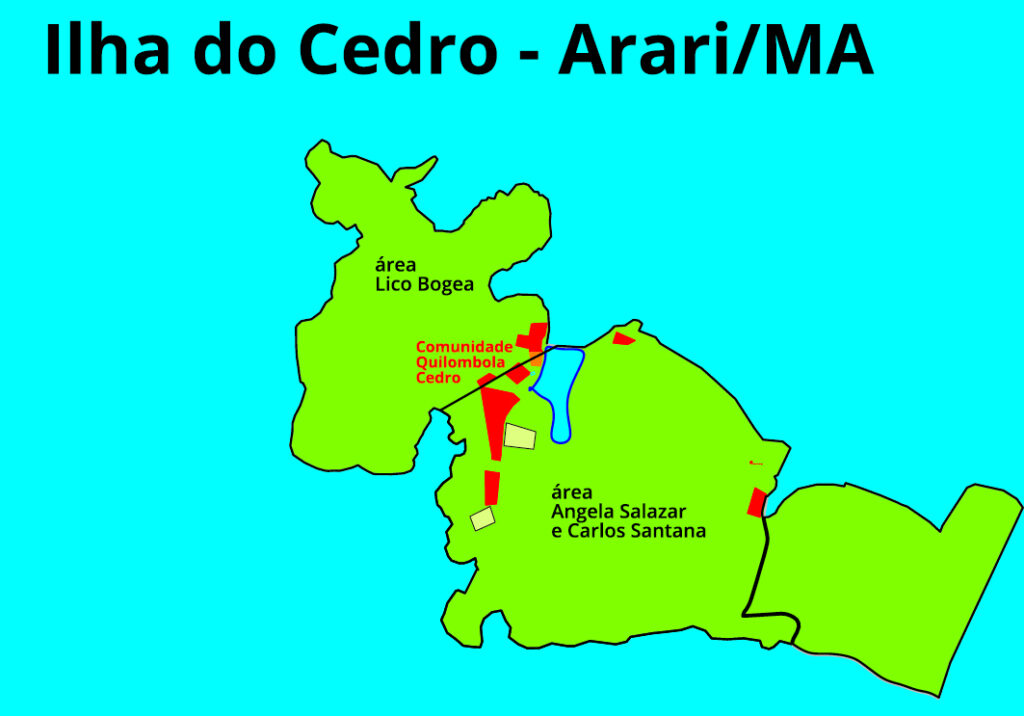

Part of the Amazonian area in the northwest of Maranhão state, Arari is formed by areas flooded annually by the Mearim River. Cedro is located on an island of the same name bathed by saltwater and legally it’s a Federal area owned by the Navy.

The communities’ livelihood is mainly based on fishing in lakes that, in the dry season, concentrate fish in flooded areas. These areas, called fields, are traditionally used collectively by the surrounding communities but have been occupied by rice producers and buffalo farmers in recent decades. The field fencing and the type of livestock they raise impact the natural resources and the quilomobola’s access to fish.

The agribusiness presence in Arari has increased in recent years due to the city’s proximity to two ports under construction.

The Arari floodplains comprise a territory of almost 2 million hectares of public lands that form an Environmental Protection Area. A 1991 state decree creating the protected area establishes the importance of lakes for feeding low-income populations and prevents the “extensive and abusive breeding of buffalo cattle” on the fields.

Despite the decree, the activity has been growing unchecked in the region. Attorney Carlos Santana Lopes, bought his 104.35-hectare property, located on the territory claimed by the Cedro community, for a bargain of R$7,280 (about US$1,380). He purchased it from a city public servant named Jurandir Araújo Aires, as indicated in the property certificate.

Cedro and Flexeira quilombola communities have been waiting since 2019 for land regularization by the Maranhão Land Institute. There has been no progress on the request. Their territories are not certified by the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform nor the Palmares Foundation, a public foundation created to promote and preserve afro-descendant culture in Brazil.

As the land conflict has intensified in the region, the communities began to organize themselves to protect their areas by removing electric fences and buffaloes from the fields.

“Just to give you an idea, in 2014 families no longer had fish to eat,” Laudivino says. He was born and has lived in Flexeira for 46 years. “We’ve been here a long time. My grandfather was born and died here at the age of 98.” Laudivino says that after reporting the conflict to numerous authorities, including the Environment State Secretary, and not getting any answers, they decided to take the animals out on their own.

“We don’t have any problem with the pastures, we just don’t accept them putting buffalo and wires in the fields,” he says. In addition to the reduction in fishing, Laudivino says the farms’ bodyguards kill the pigs raised by the communities.

In 2018, the state government launched the “Baixada Livre” operation with the aim of inspecting the illegal fences over the Arari fields. The Operation Action Plan stated that the field fencing and the buffaloes breeding caused numerous conflicts “that span decades” and pose a risk to “personal safety, life, freedom to come and go, work, income and food security for communities residing in the region”.

In its final considerations, the document recognized that farmers appropriated the floodplains of the Baixada Maranhense area and that it is “illegal”. After pressure from the farmers, the operation designed to inspect the illegal fences over the Arari fields was not carried out.

“The police know everything and do nothing”

Iriomar Teixeira de Lima, a legal advisor to the Forums and Citizenship Networks movement in Maranhão state, has represented the communities since 2017. He understands that land ownership regularization in the region is urgent since the fencing of the fields has “suffocated” traditional communities. Lima points out that not only the complaints against land grabbing have been ignored, but there is a criminalization of quilombolas by the local authorities. “The authorities have become enemies of the people,” he states.

In the past four years, 10 quilombolas were arrested in Arari for participating in collective actions to remove the fences. In addition to Laudivino and his four relatives, five other warrants were served in 2019 against Cedro quilombolas. The charges range from vandalism to gang formation and criminal association. The lawsuit that led to the arrests also demanded the preventive detention of the quilombola’s lawyer himself.

Lima also points out the State’s omission in the face of the murders. “Despite great pressure from peasant organizations to investigate the murders as a land conflict, the state government practically ignores it. This is turning a blind eye to the evidence because, looking at the city history, before the community organized to remove the fences, there was no such crime”, he says.

The first two murders took place on January 5, 2020, and are the only ones whose investigation pointed out to suspects. Juscelino Fernandes Diniz and his son Wanderson de Jesus Rodrigues Fernandes were executed with firearms in the presence of other members of the family, including kids, in Cedro community. According to the testimony of the quilombolas, the shooters arrived in the community and their homes hooded, wearing Civil Police vests and saying that they were serving an arrest warrant.

The police investigation, however, concluded that the murders were the result of an argument with the farm’s caretakers about raising pigs. Two suspects were recognized by the victims’ families and were charged, but they were not preventively arrested because more than 60 days had elapsed since the crime.

Lima and quilombola leaders question the line of the investigation, claiming that the police are trying to separate the crime from the land conflict in the region. The quilombola Valéria*, a Cedro resident, reports that the community does not receive information about the progress of the investigation. “There are no answers for the community. We don’t know if they have any involvement with the land grabbers, nothing. We report, make notes, demand a statement from the government, but we never get an answer”, she says.

Regarding Quiqui’s case, Valéria says the community is bewildered. “He was a person who didn’t get into any trouble, his only conflict was the fight for land rights here in the community,” she says. “They try to eliminate the quilombo leaders, the people who are fighting for our resistance, facing the large estates. They were already threatening us with prison and now they have decided to eliminate him by killing”.

There are no answers for the community. We don´t know if they have any involvement with the land grabbers, nothing. We report, make notes, demand a statement from the government, but we never get an answer.

*Valéria, quilombola leader

The Flexeira quilombolas also lack information about the investigations into the murders that took place in the community last year.

On June 2, 2021, quilombola Antônio Gonçalo was washing his motorcycle in front of his house when two men shot him. On the night of October 29, quilombola João de Deus Moreira Rodrigues was shot by gunmen while he was sitting in front of his house. Rodrigues had previously survived another attack, when he was shot twice in the back on December 7, 2020.

On the occasion of the murders of Juscelino and Wanderson, a public letter signed by several quilombola and peasant associations, unions and political parties, alerted that the deaths were carried by private landowner militias.

In a note, the Secretary of Human Rights and Popular Participation of Maranhão reported that “the traditional communities of Arari are assisted by the State Commission for the Prevention of Violence in the Countryside and in the City (Coecv), that the attempted murders are being investigated and that the victims and family members were taken in by the state’s protection programs”. The Secretary also reported that the community’s complaints were forwarded to the District Attorney’s office and the state’s Public Defender’s Office.

Quiqui’s family, according to Valéria, had asked for state protection while the quilombola leader was hospitalized, fearing that there would be another attempted murder. “But then he died and the State did not respond to anything else, nor did it even send condolences to the family.

Juscelino and Wanderson were among the five Cedro residents who were arrested in 2019 for having organized to tear down electric fences around the community’s fields. José Domingos, another quilombola who was also arrested at the time, survived an assassination attempt on December 17th.

Juscelino also responded to two of several lawsuits imputed by landowners with whom the communities have conflicts. The lawsuits accuse the quilombolas of “dispossession or disturbance” and aim to prevent the construction of new houses or swiddens on the lands they traditionally live in. One of the lawsuits is focused on preventing the opening of a path for quilombola children to travel to school since the path historically used by them is now used to raise buffaloes.

Laudivino is categorical in stating that there is a relationship between the dispute over land and the murders. “We certainly believe that the land grabbers are behind [the murders]. They come together, form groups and give strength to each other.”

The quilombolas resent the public authorities’ lack of action. “The police know everything, but do nothing. When we file a police report, nothing happens, but when the farmers do, the police come to intimidate us and force us to testify,” he says.

In 2020, after the murders of Juscelino and Wanderson, the quilombolas organized a demonstration in front of the Civil Police station, carrying images of coffins to symbolize the murdered. A new investigation was then opened by the police, accusing the protestors of making death threats to police. Antônio Gonçalo, one of the Flexeira residents murdered last year, was among those accused in this investigation.

According to lawyer Iriomar Lima, the Arari Civil Police chief at the time, Alcides Martins Nunes Neto, was removed by the Public Security Secretariat in 2020, after numerous complaints from the quilombola organizations. “It was clear that he had taken part. He would never investigate anything that the community reported, but to the other side he was quite diligent,” Lima says. Despite the removal, no internal procedure was opened against Neto.

In November last year, Jan Jarab, UN Human Rights Representative for South America, was in Brazil and visited the Baixada Maranhense quilombola communities. There, he heard reports of violence and murders against local leaders. Jarab also met with the state governor, Flávio Dino, and with the Federal Public Defender’s Office, as well as members of traditional communities and civil society. The findings should be included in the next UN Human rights report.

Powerful among the land grabbers

Lopes is a member of the Maranhão State Breeders Association (Ascem), an organization of ranchers with an important role in the state government. Their representatives are often received by institutions and public officials to discuss their demands.

In June 2017, an article published by the state news agency reported the visit of Ascem members to the Itaqui Port, in the state capital São Luís. On that occasion, they were received by the president of Maranhão Port Administration Company. In September 2019, Ascem members visited the president of the Maranhão Justice Court and asked for greater participation by the Judiciary in the Agricultural Exhibition of Maranhão. “The Judiciary services have great social reach and will be very important for the community and the citizens who will attend the event,” said the president of Ascem at the time, according to the news story on the Court website.

One of the lawsuits filed by Carlos Santana Lopes and Angela Salazar is a writ of mandamus at SEMA, in August 2018, aiming to prevent Maranhão state from removing its electric fences from Arari public fields.

The couple filed two lawsuits accusing murdered quilombola Juscelino Fernandes Diniz and his family of dispossession and disturbance for having started building a brick house within the area where they raise buffaloes. The couple filed another lawsuit against Rogério Rodrigues (Quiqui’s son), Sebastião Verde Diniz (brother of quilombola José Domingos, who suffered attempted murder in December 2021), and two other quilombolas, with the aim of preventing the residents of Cedro to make their swidden.

Another rancher in conflict with the Cedro community is Francisco de Assis Bogea, known as Lico Bogea. Currently, Bogea is an alternate city council member at the Arari City Council. When accounting for his election campaign in 2020, he declared a piece of land in “Cedro village” valued at R$300,000 and a house in the community at R$100,000, in addition to 80 heads of cattle.

In September 2021, Bogea filed a lawsuit against Quiqui and other quilombola leaders, alleging that he was being prevented from building a house on his property, the 211-hectare Mamãe Princesa Isabel farm.

Valéria sees the multiple lawsuits against quilombola families as an attempt to “take over all of Cedro’s land”. “We can no longer accept this violence. The land is ours, we are descendants of quilombos, from ancient times, and we have lived here for over 200 years.”

The report tried to contact the judge Angela Salazar and State Deputy Attorney Carlos Santana offices and also their respective lawyers in the cases against the quilombolas, but received no response. Contacted, Lico Bogea and his lawyer also did not provide an answer by the time of publication.

*Valéria is the fictitious name of one of the quilombolas who preferred not to be identified for fear of retaliation

This story was produced with support from Report for the World, a The GroundTruth Project initiative.