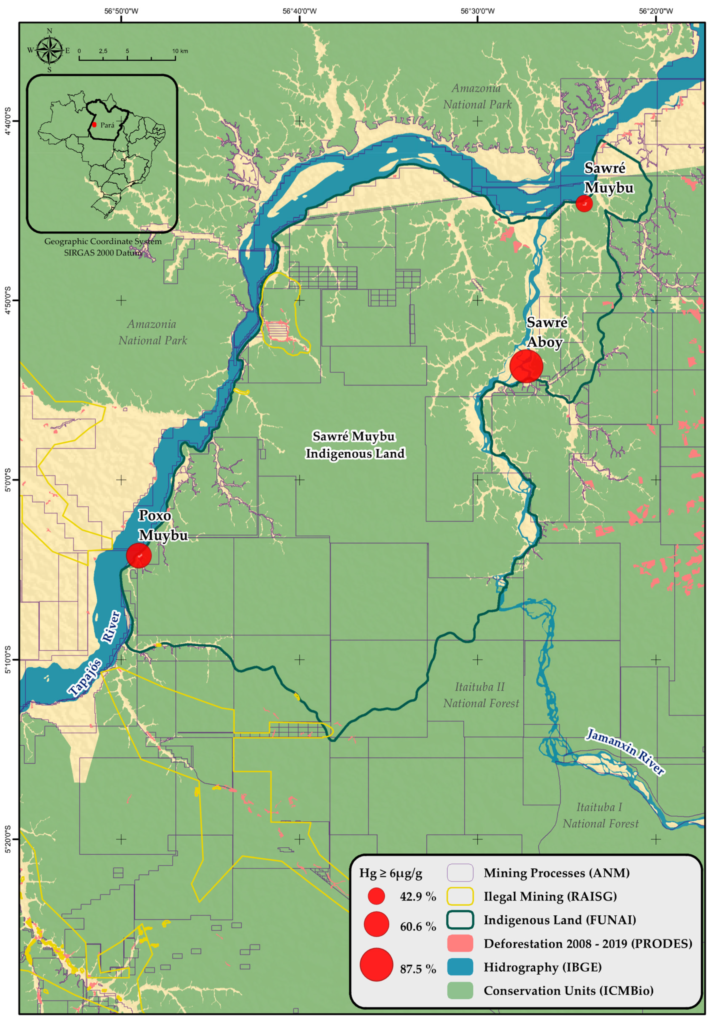

Studies by Fiocruz show that 60% of the indigenous people of the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Land have this toxic metal in their bodies above the limit tolerated by the WHO. Mining in indigenous lands has grown by almost 500% in a decade.

Seven studies by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) show that women and children are the most vulnerable to mercury poisoning, which affects all 200 people in the villages of Sawré Muybu, Poxo Muybu, and Sawré Aboy, in the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Land belonging to the Munduruku people in western Pará. The source of the contamination is gold mining, which has grown by almost 500% in indigenous areas, especially in the Amazon, since 2010 and today has the incentive and support of the Bolsonaro government. Lands, fish, and water are contaminated, bringing risks to rural and urban populations.

The surveys, which have been carried out since 2017, were recently finished by Fiocruz, and were released in the first half of November. According to the study, six out of ten women of childbearing age in the villages have more mercury in their blood than the highest tolerable levels according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and environmental agencies in the United States and the European Union. Severe motor delay and anemia were identified in an 11-month-old infant. Two Munduruku children, aged 12 and 14, who ate fish at least three times a week have vision problems, memory loss, and tremors.

The average contamination above tolerable limits is of six out of ten indigenous people (40% in Muybu village, 60% in Poxo, and 90% in Aboy). These territories are on the banks of the Tapajós and Jamanxim rivers, where mining has existed since the 1950s. In April, environmentalist Cássio Beda died after two years of living and consuming fish in the Tapajós River basin, where he supported the demands of indigenous peoples.

Everyone from the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Land is contaminated by mercury poisoning and six out of ten have more mercury in their blood than the highest tolerable levels according to the WHO.

“Indigenous peoples in the Amazon depend on natural resources to live, but the growing impacts of human activities threaten their health and livelihoods”, highlights the most recent study by Fiocruz, published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. The surveys began after complaints about mercury contamination by entities such as the Pariri Association, which represents 11 Munduruku villages in the Middle Tapajós. Tests were carried out on blood nad and also on the fish consumed took place in late 2019.

Paulo Basta, the coordinator of investigations into mercury contamination among the Munduruku, warns that all the inhabitants of the assessed villages are at high risk of illness because there is no safe level of mercury in the human body. “It is a calamity that associates sanitary and environmental crises, with an increase in contamination and deforestation and a continuous violation of rights, including invasions by miners and loggers that have dragged on for decades”, warned the Fiocruz researcher.

It is a calamity that associates sanitary and environmental crises, with an increase in contamination and deforestation and a continuous violation of rights, including invasions by miners and loggers that have dragged on for decades.

Paulo Basta, Fiocruz researcher

Studies make it clear that eating fish in these villages increases the chances of contamination. The human body does not have mercury and does not eliminate what it absorbs through direct contact or consumption of contaminated animals and water. The toxic metal is associated with infant malformations and neurological diseases such as dementia, dizziness, tremors, hearing, and vision problems. The effects are cumulative and can lead to death.

Alessandra Korap Munduruku, of the Pariri Association, assesses that many illnesses and deaths are not properly connected to the pollutant due to the precariousness of health services in the rainforest, especially for indigenous people. That is, when they get sick or die, their medical reports and death certificates do not associate deaths with mercury. “Fish with mercury and pesticides are not tied down, they move up and down rivers. Fish, the only food source for many people, is no longer a safe food in the Amazon”, he said, grievingly, in a recent debate promoted by Fiocruz.