Lawyer Luiz Eloy Terena, a Representative of the Coalition of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib) at the Brazilian Supreme Court hearing in question, comments on the importance of demarcating indigenous lands for the protection of the country’s natural resources. MapBiomas data shows that only 1.6% of Brazil’s deforestation occurred in Indigenous Lands over 36 years.

About 6,000 indigenous people from 173 different ethnicities, coming from all of Brazil’s states, camped on the Esplanada dos Ministérios – the Brazilian equivalent to Washington’s National Mall – this week in the biggest indigenous movement since the 2005 Terra Livre Camp, still considered a landmark in the struggle for indigenous peoples’ rights in Brazil.

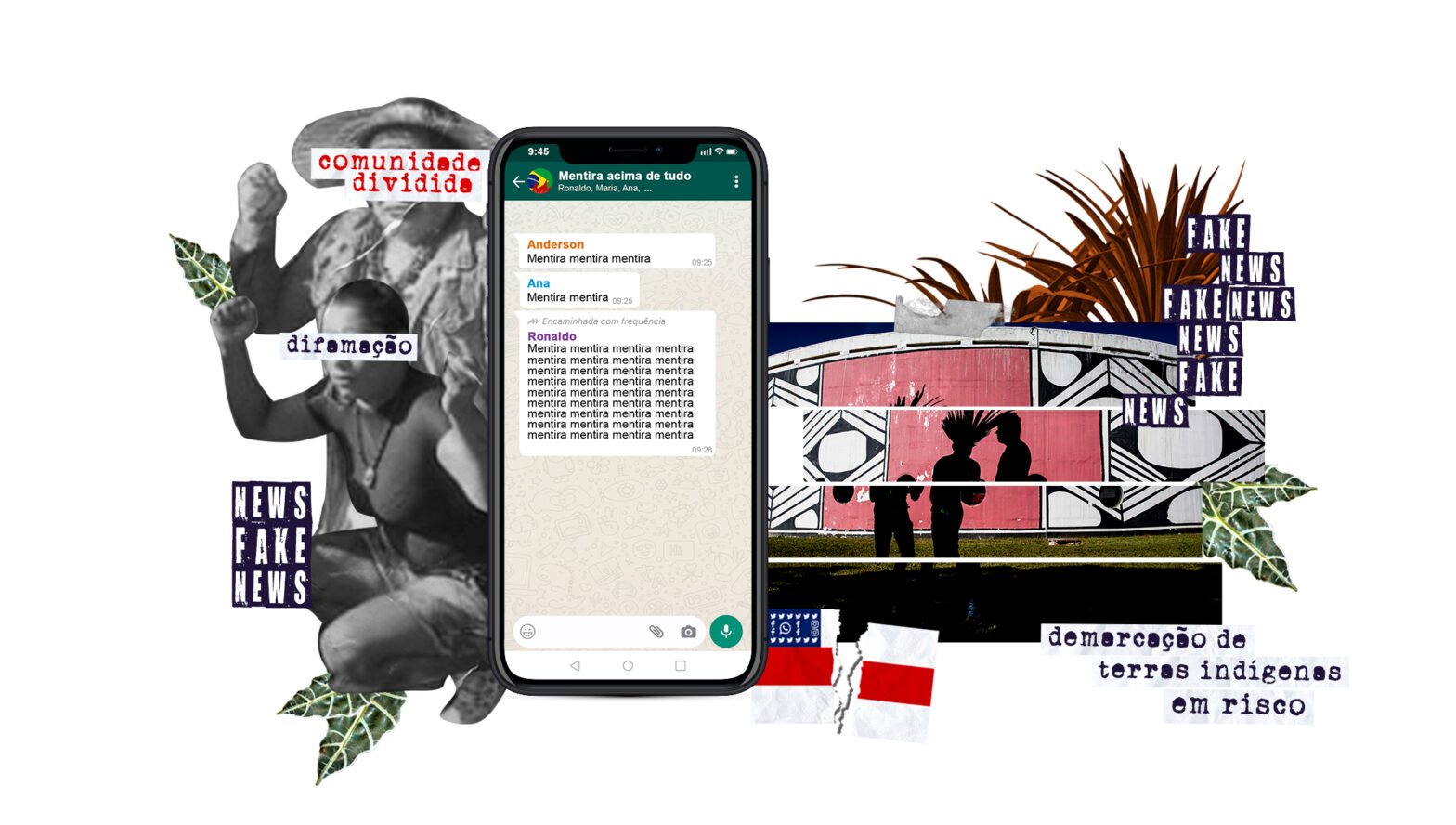

The reason is the Federal Supreme Court (STF) hearings regarding the “Marco Temporal”, or time limit thesis, which was resumed this Wednesday, August 31st. The “Marco Temporal” is a legal thesis that prevents the demarcation of lands not occupied or legally disputed by indigenous peoples on the date of October 5, 1988 – the date when our current constitution was enacted. Before the current constitution, indigenous people were under the tutelage of the State and could not go to court on their own to fight for their rights, an argument that weakens the defense of this thesis by agribusiness representatives.

A decision favorable to indigenous peoples could accelerate hundreds of land demarcations currently bottlenecked in the Executive or Judiciary. Delays in the judgment or an eventual approval of the Marco Temporal thesis would pave the way for millions of hectares claimed by indigenous peoples to be used for farming, mining, energy generation, and other economic activities. Today, the 723 Brazilian indigenous lands make up approximately 14% (1,174,273km2) of the national territory and help to protect our biomes. According to data from MapBiomas, only 1.6% of all deforestation between 1985 and 2020 occurred in these areas. About 98% of the total area of all Indigenous Lands are in the Legal Amazon, the region where deforestation has grown the most according to their latest report.

Map showing forest cover (in dark green), husbandry (in yellow), and soybean cultivation (pink) areas according to data from MapBiomas. In white, the limits of Brazilian Indigenous Lands. Move the slider to compare deforestation in 1985 (left) and 2020 (right).

MapBiomas analyses consider both demarcated territories and territories awaiting demarcation. The clearest example of this barrier to deforestation created by indigenous lands is the Parque do Xingu Indigenous Land. Satellite images taken since 1985, when monitoring began, show that the site has remained a green island over these 35 years while the degradation of vegetation cover has completely surrounded it.

The Parque do Xingu Indigenous Land was the first large indigenous land demarcated by the Brazilian government, 60 years ago. It encompasses 2.8 million hectares and is the home of 16 indigenous peoples. But the threat of deforestation is lurking about, as shown in the images analyzed by MapBiomas.

Satellite images show the Parque do Xingu IL (in the center), which preserves its forest cover, while degradation of the vegetation cover has advanced in all surrounding areas. In white, the limits of Brazilian Indigenous Lands. Move the slider to compare deforestation in 1985 (left) and 2020 (right).

To explain the environmental impacts and the decisive importance of the Federal Supreme Court (STF) debates to indigenous peoples, we listened to the lawyer Luiz Eloy Terena, who represents the Indigenous Coalition of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib). A postdoctoral fellow at the School of Higher Studies in Social Sciences, Paris, Eloy gave an oral argument this Wednesday at the Supreme Court in which he analyzed the issue and reaffirmed respect for the Constitution, which is based on the concept of tradition to define the demarcation of indigenous areas.

Check out the main excerpts from the InfoAmazonia interview below:

InfoAmazonia – How did the Marco Temporal (time limit) thesis come about and what is your assessment of it?

Luiz Eloy Terena – This thesis emerged in the legislature in the early 2000s, when parliamentarians connected to agribusiness raised the need to establish a framework so that indigenous lands “did not occupy all of Brazil”. In 2009, when the Supreme Court was analyzing the case of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land, in Roraima, the time limit thesis appeared at the end of the process as one of the conditions for the delimitation of the territory. This took the time limit thesis to the Judiciary. But the thesis has no legal basis or support in the Federal Constitution, it is just a political-ideological theory to eliminate indigenous rights in the dispute for land.

What is the status of the trial today and what other issues are being evaluated?

Minister Alexandre de Moraes requested a technical interruption of the trial one minute after it should have started in June. The case’s rapporteur, Minister Edson Fachin, has already declared that he is against the time limit thesis. We believe that most ministers today are also against it. In the same process and linked to the time limit thesis, the suspensions of Opinion 001/2017 of the Attorney General’s Office (AGU) will be evaluated, which the government uses as if it were an administrative time frame to paralyze and try to reverse demarcations, and of lawsuits that could expel populations by nullifying demarcations during the covid-19 pandemic.

There is no longer any doubt about the multiple benefits of demarcating indigenous lands. Overthrowing the time limit thesis will reinforce the proven compatibility of indigenous territories in protecting ancestral peoples and cultures, as well as natural environments and resources. These areas maintain peoples’ traditional ways of life while also benefiting all of Brazilian society by helping to balance the climate, maintaining water sources and biodiversity.

Luiz Eloy Terena, advogado da Apib

If most ministers are against the time limit thesis, why hasn’t the ruling come faster? Are these postponements done to favor someone?

There’s a lot of pressure. Agribusiness and other sectors interested in taking over indigenous lands want to postpone the judgment while they try to pass laws and other regulations to open the territories to economic activities such as mining, energy generation, oil extraction, and infrastructure works. One of the proposals is Bill 490/2007, by former agribusiness congressman Homero Pereira (from the state of Mato Grosso). In practice, this bill, which the lower house of Congress will analyze, ends demarcations, allows for indigenous land borders to be reviewed, and opens indigenous lands to economic exploitation. If measures like this are approved in Congress, lawmakers can change the Constitution and the decisions of the STF. That’s why we’re in a hurry. In March of last year, Funai managed to cancel the demarcation of the Guasu Guavirá Indigenous Land in Paraná, where the Guarani live. This ruling, based on a first instance decision in Federal Court, favored municipal governments that challenged the traditional occupation of the area. By overturning the time limit thesis, we will advance with demarcations and guarantee indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands.

Recent surveys show that only 1.6% of total deforestation in Brazil between 1985 and 2020 took place on indigenous lands. What positive effects are brought about by protecting these areas?

There is no longer any doubt about the multiple benefits of demarcating indigenous lands. Overthrowing the time limit thesis will reinforce the proven compatibility of indigenous territories in protecting ancestral peoples and cultures, as well as natural environments and resources. These areas maintain these peoples’ traditional ways of life while also benefiting all of Brazilian society by helping to balance the climate, maintaining water sources and biodiversity. That’s why we’re encamped in Brasilia. Therefore, indigenous peoples will continue to fight and will protect their lands with their lives.

How many lands are currently waiting in line for demarcation? What is the situation of the people who would benefit?

We currently have 829 administrative processes stuck and an unknown number of legal processes questioning the demarcation of indigenous lands. All this needs a more solid legal basis to take off, which would come with an STF ruling throwing out the time limit thesis. This would be a relief and a hope even for many families and communities that continue to camp along roadsides and farms. All of them carry a burden and go without access to land, health, and education. Their fundamental rights are denied.

Reporting by InfoAmazonia for the PlenaMata project .

Eloy Terena Photo: Vinícius Loures/Agência Câmara