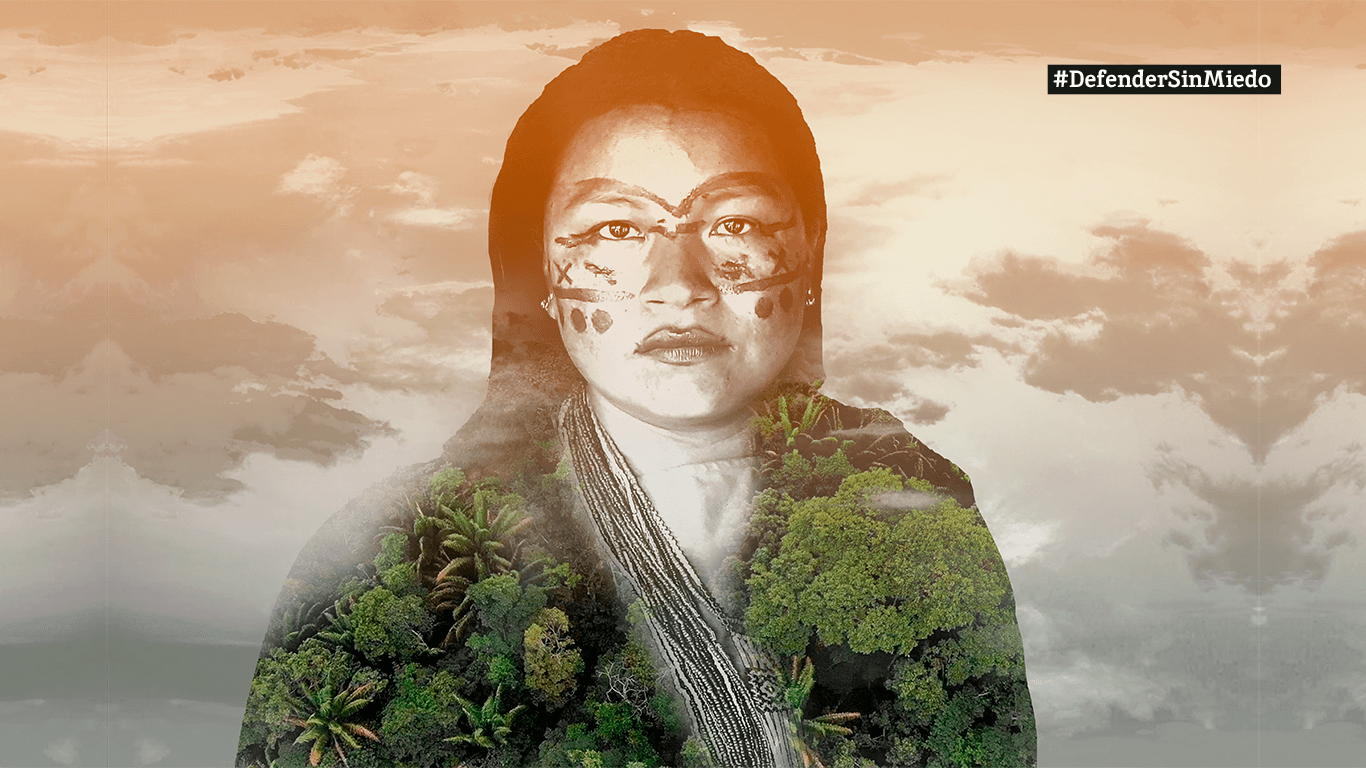

Inspired by Wänä’cä, a leader who is mentioned in the ancestral songs of the Huöttöja people, Hortimio Ochoa is the visible face of defense of the Cataniapo hydrographic basin in the Venezuelan state of Amazonas. It is an area subject to increasingly evident pressure associated with mining, deforestation and the incursion of illegal armed groups

By María Ramírez Cabello

The name of Wänä’cä resounds in the songs the Huöttöja shamans of the Venezuelan Amazon sing in their language during ceremonies before initiating spiritual revenge against those who have violated the tranquility of their people. Wänä’cä was a prominent indigenous leader during the Spanish Conquest at the beginning of the 17th century, when outsiders entered the region to conquer the Huöttöja’s lands.

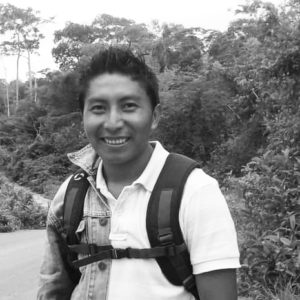

At the time, Wänä’cä assembled a team with members of the community to defend themselves. Their aim was to drive out the conquerors, who were subduing the natives by force of arms, and to reestablish peace. This is how Hortimio Ochoa, the youngest leader in Amazonas tells the story. “For us, he was like Simon Bolívar, and he has been an inspiration in my struggle,” says Hortimio, a 33-year-old man who coordinates the United Huöttöja People’s Organization – Piaroa del Cataniapo. Cataniapo is an important natural water basin covering 153,401.92 hectares. It is inhabited by a multiethnic population comprised of 22 communities, with some 3,170 inhabitants, a few kilometers from the capital city of Puerto Ayacucho in southwest Venezuela.

The Cataniapo basin, which extends across the State of Amazonas, bordering Colombia to the west and Brazil to the south, is one of the most biodiverse corners of the nation. It’s officially declared protected areas confirm this fact: a biosphere reserve, four national parks, fifteen natural monuments, and a forest reserve. Amazonas is also the second state in the country with the largest indigenous population: 76,314 people representing 33 different ethnic groups, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (INE). The Piaroa population, of which Hortimio is a member, is the second most numerous.

Hortimio’s traditional name is Reje’cha. It means lord of the land, a definition that fits the job he does, which is to defend his territory from extractivism, invaders, deforestation, and incursion by illegal armed groups. He also works to promote his people and encourage their development, with a particular emphasis on rescuing their ancestral culture and knowledge. The meaning of his name also connects him with that of his main reference: Wänä’cä.

The lord of the earth says the threat to biodiversity in the Cataniapo basin is evident. Just as Wänä’cä had to confront colonizers, Hortimio – a dark-skinned man of medium height, outgoing, and in good spirits in his role as a leader – has had to work hard to prevent incursion on the part of illegal armed groups and miners who extract gold from the bowels of the forests, with the Venezuelan government as an accomplice. In this area, several investigations by journalists and international organizations, such as Crisis Group and Insight Crime, have revealed the presence of armed groups from the neighboring country of Colombia, including dissidents of the former guerrilla Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and members of the National Liberation Army (ELN).

Hortimio vigorously insists he does not fight alone. He is accompanied by the council of elders in his community and by his team, a group of eight men and women who are proactive and unstoppable when it comes to overseeing their territory.

Hortimio vigorously insists he does not fight alone. He is accompanied by the council of elders in his community and by his team, a group of eight men and women who are proactive and unstoppable when it comes to overseeing their territory.

He says the indigenous people of his town closed down a lengthy clandestine road in June 2020, which had been opened by miners to connect the area to the northern border with Brazil. Months ago, in February 2020, prior to the quarantine decreed in response to the crisis caused by the COVID-19 global pandemic, FARC dissidents settled on his community’s land. Hortimio says 700 indigenous people from Cataniapo marched to a wooded area in the jungle to defend their territory and expel the armed dissidents. “They left again (…) [and] have already invaded several territories. They look for natural resources,” he adds.

Hortimio also recalls that four days before the end of 2019, when accompanied by a group of indigenous people, he exchanged words with the commander of the dissident group, telling him “this is our territory” and demanding they leave.

“They were armed and they knew this was the only free territory. We march and we talk with them, because we are not people of war. They said they were from the government and claimed to be strategic allies of Venezuela, but we answered ‘no.’ ‘We have approved no such agreement and anything that is not approved by the National Assembly is null and void,’ I said. And, they left.”

Ancestral Habitat and Protective Zone

The Venezuelan Amazon includes the states of Bolívar, Amazonas and Delta Amacuro. The Cataniapo River, in Amazonas, is a large waterway lined with dense trees. It flows through a fragile and pristine area with one of the most preserved forests in the country. This river is the main source of water for Puerto Ayacucho, which is the capital city of Amazonas.

Due to its strategic nature in terms of water supply, the basin is classified in the Water Act as a protective zone, which is one of the legal names for areas that are under special management. Despite being the ancestral home of the Huöttöja people of Cataniapo, members of other ethnic groups, such as the Curripaco, Guajibo, Baniva and Jivi, also live there.

Hortimio makes his home in Sardi, the last landed community in Cataniapo, an esplanade on the banks of the emerald waters of the river of the same name, a channel to the rest of the settlements along its banks. The houses in Sardi are made of adobe. Its main productive activity is centered on family conucos (crops) of cassava, tupiro, pineapple, manaca, seje, copoazú and plantains, among other items. People produce what they need for their own consumption.

In the afternoons, football brings together the youngest, and Sardi treasures a large and extremely well-kept field of natural grass where this sport is played. However, during the school year or if any medical emergency arises, the inhabitants of the community must walk an hour and a half, round trip, to the school and the medical dispensary in the neighboring community of Gavilán. When they arrive, they find the physical infrastructure, but no medicine or medical personnel. It is a lack that is repeated in the indigenous communities throughout the Amazon.

Hortimio studied Physical Education and Sports in the Andean state of Mérida at the University of Los Andes in the west of the country. Although he acknowledges that young people are tempted to abandon the ways of their culture when they move the city, he did not succumb to the charms of urban life. The year was 2009. At the university, he was invited to a meeting with people from other indigenous groups to analyze the threats and pressures they suffer in Venezuela and to reflect on the work of Sabino Romero, a Yukpa leader who was assassinated four years later, in March 2013.

“I realized my people had to prepare and to convey the message to defend the environment (…) they made me understand that everything you are depends on your predecessors. My ancestors left me a story for the world.”

A year after graduating, Hortimio began touring communities in the heart of Amazonas. In 2012, he legally registered his organization, doing so with legal advice and guidance from the university. It was the first group of its type in the region, where the only prior associations were those promoted by the government. Since the organization was established, it has seen eight years of work with special support from the Human Rights Office of the Vicarate of the Catholic Church. “Our struggle is framed by defense of life and the right to a free space and peace, because salvation of the planet lies with ancestral wisdom and traditional knowledge, and my duty is to transmit it from generation to generation,” he says.

Socio-Environmental Pressures

Humid tropical forests predominate in the Venezuelan Amazon. It is a land of mountains, peneplains, and valleys. Flora of the Venezuelan Guayana, published in nine volumes between 1995 and 2005 by botanists Julian Steyermark, Paul Berry, Kay Yatskievych and Bruce Holst, indicates that approximately 4,000 plant species grow in the area. Of these, no less than 1,500 are endemic to the region.

Another mandatory publication for environmentalists working in the area is the 2015 edition of The Red Book of Venezuelan Fauna. It says there are at least ten species in the State of Amazonas that are at risk: the manatee, classified as critically endangered; the cachicamo, the sword-nosed bat, and the water dog, classified as endangered; and the anteater, the southern spider monkey, the bearded monkey, the bush dog, the cunaguaro, and the harpy eagle, which are considered vulnerable.

Two years ago, the Amazon Network for Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (Raisg) mapped 2,312 mining points in the Amazon, a region of South America that extends between Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, Ecuador and French Guiana. More than 80 percent (1,899) were in Venezuela. The World Assembly for the Amazon specified that Raisg has georeferenced eight illegal mining points in the Sipapo and Cataniapo river basins: six in the Sipapo Forest Reserve and two in the protective zone of the Cataniapo River basin, which is Hortimio’s territory.

The increase in mining was one of the main concerns of indigenous organizations when Nicolás Maduro’s administration approve creation of the Orinoco Mining Arc in 2016. Although it did not include the Amazon, it opened the door to greater exploitation of resources. Eventually, illegal mining expanded throughout the state (a 1989 decree prevents the extraction of minerals). Studies by environmental organizations and journalist show the government benefits from mining and, therefore, has no intention of halting it.

“There is still no mining in Cataniapo, but there is illegal mining near the town of Atures. It is being done by people who come from other countries,” says Hortimio, adding that the river is a protected area, which makes it even more valid to defend. “It is the only freshwater river that supplies the town. Our duty is to protect it and the biodiversity in the basin,” he highlights. In addition to being a waterway and a water source, the Piaroa have a strong spiritual connection to the Cataniapo River. “Auxiliary agents” – which are similar to the territorial guard – protect the basin. Even though armed groups have entered the area, the community has received no direct threats.

Hortimio’s motivation increased when the community warned that mining development promoted by government institutions “is about destruction; there is [a] socio-environmental impact.” “All of this prompted us to create various working committees to be able to have an organization that can be at the forefront of environmental and territorial defense,” says the indigenous leader.

The struggle to protect natural resources generates many risks. In this respect, Venezuela ranks seventh as one of the most dangerous countries in the world, according to the NGO Global Witness, which revealed in its latest report, Defending Tomorrow, that eight environmental activists were murdered in Venezuela during 2019, out of 212 in 21 nations. The report also states mining was the sector associated with most of these crimes, with 50 activists assassinated worldwide.

“Hortimio’s work is fundamental. He knows how to bring the message of this struggle to the young people of his generation, which is also a mandate from the elders and wise men of his people: the Piaroa, both those who are here today and those who are present on another level. His leadership not only vindicates the territorial struggle of the Piaroa, but also their social and cultural rights, which are increasingly threatened by illegal groups, individuals and even the government itself,” highlights Luis Betancourt Montenegro, a member of the Amazon Research Group (Griam).

Bioculture and Agroforestry

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought additional pressure to bear on indigenous communities and on the Amazon region, and has halted some of the projects Hortimio’s community had hoped to promote this year, although their efforts to defend the land remain intact. By August 2020, there were still no cases of the novel coronavirus in the area where Hortimio lives, but 3,584 cases of infection were reported in the Venezuelan Amazon as of September 10, mostly in the State of Bolivar.

“Since the onset of the disease, contact with advisors has declined. We had a project with international cooperation, but everything closed down because of the pandemic. All the financial support has been reduced,” says Hortimio. The sale of agricultural products such as manioc, manaca, cacao, and copoazú also stopped, because the quarantine prevents members of the community from traveling to town and there are difficulties in buying fuel, despite the fact that farm produce is their main source of income.

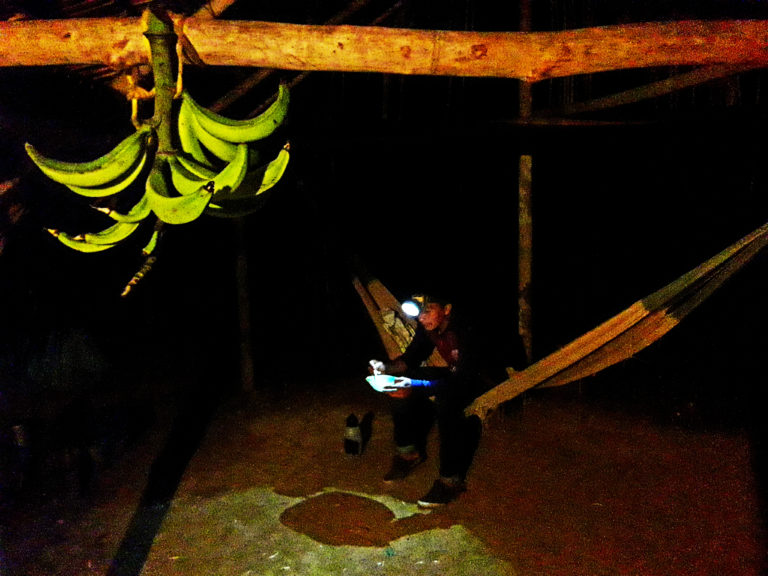

Even so, Hortimio does not stop. Small assemblies are being held in his community “because there are problems,” and sports activities for young people are still ongoing, as are several agroforestry projects (a land-use system that integrates trees, cattle and pasture land within the same productive unit), in addition to efforts to rescue the community’s identity. One of these initiatives focuses on bioculture, which “is life culturally,” he explains. With the support of the community’s elders, the United Huöttöja People’s Organization – Piaroa del Cataniapo is gathering information on the community’s entire body of knowledge with respect to natural healing. The idea is to compile a medicinal catalog.

“Today’s generation does not know the origin of our people, the cosmogonies and the practices of shamanism, and how people can be healed naturally through ethnomedicine,” says Hortimio. A recipe can be drawn from ancestral wisdom to cure a person, and “that cannot be lost for any reason; there has to be a work team to gather all the essential information,” he insists.

Luis Bello, founder of the Vicariate’s Human Rights Office and current operational director of the Wataniba Amazon Socio-environmental Working Group, highlights identity and the link to ancestral wisdom as the primary features that nurture Hortimio’s commitment to a comprehensive defense of his people based on a territorial and environmental point of view. “He moves not only within his ancestral territory, which is already a value in itself, but [also] in the world of his identity. His identity and ethnicity are very clear, which is a source of inspiration,” he says.

“The role he plays in the area has a constitutional basis, but also [rests on] a specific right established in the Organic Law on Indigenous Peoples and Communities,” Bello stressed.

In the face of destructive activities such as mining, Hortimio promotes planting cacao, copoazú, and manaca. He does this in conjunction with his family, his team, grassroots organizations, and the ever-wise umbrella of the elders of the community. “I want my generation to be free and at peace in their land; that is our project, [to be] free of invaders. We have the land our ancestors left us, and that is how we are going to develop as a people,” he insists.

According to Hortimio, although the historical debt to indigenous people is growing, if the national government does not designate their lands, they will organize to defend them. This is a natural right, he emphasizes. Every step connects his people to the struggle of their ancestors and to Wänä’cä, their reference and whose name stands out in every ritual conducted by the elders who accompany their work.

(Translation: Angie Caballero)

This article is part of #DefendWithoutFear, a journalist series that tells the stories of women and men who struggle to defend the environment in a time of pandemic. Developed by Agenda Propia, in coordination with twenty journalists, editors and allied media in Latin America, the series is made possible thanks to support from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a global NGO.