At least six defenders of the environment have been killed in Latin American since 11 March, the date on which the pandemic was declared.

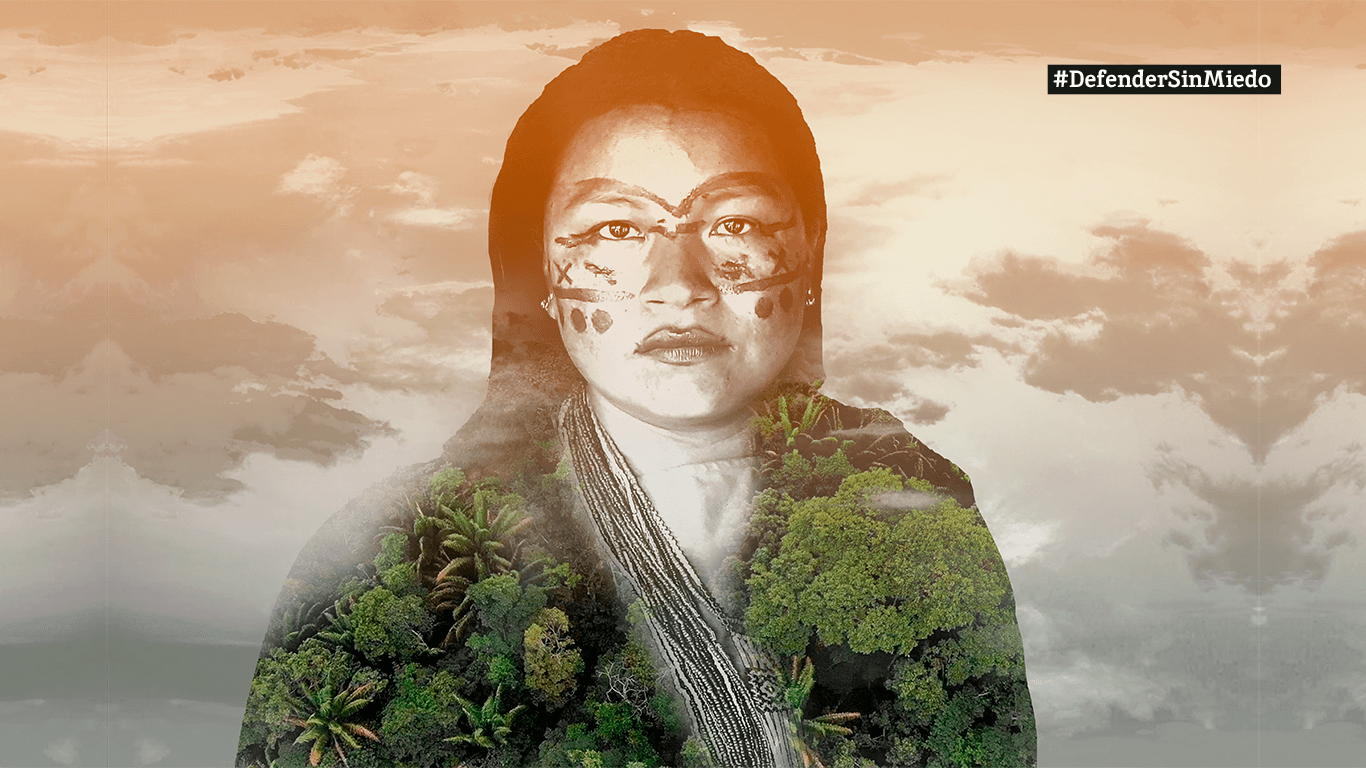

At least six defenders of the environment have been killed in different Latin American countries since 11 March, the date on which the pandemic was declared. Opening photo: Adán Vez, environmentalist killed in México (personal archive/Facebook)

By Andrés Bermudes Lleviano,

“Violence has not been quarantined”. That phrase, repeated by social and environmental leaders in Colombia, is sadly true in many Latin American countries.

At least six defenders of the environment have been killed in different Latin American countries since 11 March, the date on which the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease a pandemic.

This figure shows how, in addition to the concern of many of these communities regarding the possible advent of the COVID-19 in rural regions with precarious medical services and limited state presence, the violence continues. This is despite the fact that one of the keys to reducing the transmission of many infectious diseases is precisely, according to several scientists, preserving ecosystems such as the ones these leaders care for and defend.

Killings continue in Mexico

Adán Vez Lira has spent two decades caring for the La Mancha wetlands and mangroves, a small coastal community that looks out over the Gulf of Mexico, in the Mexican state of Veracruz, as recounted by Mongabay Latam. On the morning of 8 April, he was riding his motorcycle along a country road in the municipality of Actopan when unknown assailants shot him dead.

La Mancha, the ecosystem to which Adán dedicated his life and the neighboring lagoon complex of El Llano, are composed of an area totaling 1,414 hectares of wetlands categorized as internationally protected by the Ramsar site. Due to its ecological relevance, the La Mancha Coastal Research Centre (Cicolma) of the Institute of Ecology (Inecol) was established there. Vez collaborated with the Centre through the cooperative, La Mancha in Movement, which he helped found two decades ago.

From that cooperative, Vez managed resources for the conservation of the mangroves, organized environmental education workshops in the area’s schools and promoted ecotourism as a sustainable economic activity for the ecosystem. He was also an enthusiastic promoter of the La Mancha Bird Festival, which attracts hundreds of tourists every year to observe the shorebirds and waterfowl that come to this great bottleneck and enormously wide passage on the birds’ migration route. “It is the most important bird of prey corridor in the world!”, Vez used to boast.

It is not the only attack in the last month in Mexico. On 23 March, two gunmen killed attorney Isaac Medardo Herrera Avilés at his home in Jiutepec, in the state of Morelos.

Herrera, a former communal leader who later became an attorney, litigated on various issues of environmental interest, as Mongabay Latam described in his profile. One of them was the defense of the Los Venados property, a 56,000 square meter forest right in the middle of Jiutepec, where the then municipal president authorized a project for the construction of 400 homes and the felling of more than half its 3,000 trees.

These two cases add to the list of at least 86 defenders of the environment killed since 2012 in Mexico. In January of this year, Homero Gómez González, a defender of the monarch butterfly, was also murdered. He was found dead two weeks after his family reported his disappearance in the municipality of Ocampo, in the state of Michoacán.

Indigenous people under siege in Brazil, Peru and Colombia

The month following the declaration of the pandemic has been equally lethal for the indigenous people in the countries on the Amazon basin.

On 31 March, Zezico Rodrigues Guajajara, a respected leader of the Guajajara people living in the indigenous territory of Araribóia in the Amazonian state of Maranhão in Brazil was murdered.

Zezico was returning to his village of Zutiwa on a motorcycle when unknown assailants armed with a shotgun attacked him, the Amazônia Real website reported. Although there is no further information on the perpetrators, suspicions fall on local illegal loggers who had threatened him in the past, according to the NGO Amazon Watch, which operates in the region.

This leader, who is the fifth Guajajara Indian killed in five months and who had recently been elected Coordinator of the Commission of Indigenous Chiefs and Leaders of the Indigenous Territory of Araribóia (Cocalitia), was one of the historic promoters of the Guardians of the Forest, a group of 120 indigenous volunteers who protect the Araribóia territory from illegal logging and trade. He is also known for protecting the Awá-guajá people, who live in voluntary isolation within the same territory of Araribóia.

Data from the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) indicates that the Maranhão state is the national leader in terms of rural conflicts, with 2,539 cases between 1990 and 2018. As for the Guajajara Indians, 49 have been killed in Maranhão since 2000 – without any crime having been solved.

In Peru, the murder of an indigenous leader was also recorded. On 12 April, Arbildo Meléndez Grandes, chief of the native community of Unipacuyacu, on the border of the Ucayali and Huánuco regions, was shot dead. He was killed by one of his new workers, who was helping him in a reforestation project, while he was hunting in the bush to supply his family.

“Since he took office he has received threats,” his wife Zulema Guevara Sandoval told Mongabay Latam. When he was named president of Unipacuyacu, Meléndez decided to push for the official demarcation of communal lands, a request that had remained unanswered for more than 20 years. This work was uncomfortable for the invaders he constantly stood up to and who wanted to introduce illegal coca leaf crops into their territory. Unipacuyacu is one of the indigenous communities that defend their forest from drug trafficking and illegal mafias that continue to operate despite the fact that a state of emergency has been in effect in Peru since mid-March.

Things are equally complex in Colombia. On 23 March, Omar and Ernesto Guasiruma Nacabera, two Emberá indigenous people from the community of Buenavista in the department of Valle del Cauca, were murdered. That night, as documented by Mongabay Latam, unknown assailants arrived at their home in rural Bolivar municipality and invited them to a supposedly urgent meeting. They were shot 20 meters from the door and the assailants fled, leaving two other family members seriously injured.

Another indigenous people, the Emberá of the Pichicora Chicué Punto Alegre-Rio Chicué Reserve, on the Colombian Pacific coast, have been caught in the crossfire since 3 April because of the confrontation between two armed groups. One of these, the guerrilla group of the National Liberation Army (ELN), theoretically decreed a ceasefire throughout April, but its armed confrontation with the so-called Gaitanist Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AGC) has meant that these indigenous people living in the municipality of Bojayá, are trapped in the department of Chocó. The Emberá reported 10 grenades exploding and they are prevented from taking refuge in other towns.

COVID-19 highlights the importance of defenders of the environment

The fact that the attacks continue in the midst of the spreading COVID-19 is revealing for another reason: precisely the magnitude of this public health crisis is underscoring the role that environmental degradation may have played in its transmission and, therefore, it only emphasizes the importance of the work of the defenders of the environment.

Although there is still much to be understood about how this new coronavirus generated a pandemic and an equally widespread economic recession, there are several indications that the accelerated loss of ecosystems is also an overwhelming factor.

“Scientists warn us that deforestation, industrial agriculture, illegal wildlife trade, climate change and other types of environmental degradation increase the risk of future pandemics, raising the probability of major human rights violations”, David R. Boyd, the United Nations Special Rapporteur for the Environment and an expert in natural resource management.

Evidence suggests that biodiversity loss often increases the transmission of pathogens and that reducing the prevalence of infectious diseases is a service provided by more biodiverse ecosystems, according to a study published in 2010 in the Nature journal by thirteen scientists from nine universities and three scientific institutions.

“More broadly, biodiversity itself seems to protect organisms, including humans, from the transmission of infectious diseases in many cases. Preserving biodiversity in these cases, and perhaps generally, may reduce the incidence of established pathogens”, concluded the team led by Felicia Keesing, a Bard College ecologist specializing in infectious diseases.

This loss of biodiversity is strongly linked to deforestation and the destruction of ecosystems to expand herds of cattle or industrial crops like soybeans or oil palms, which are some of the raw materials that Latin American countries have made the focus of their exports.

For example, in Brazil’s northern region, which encompasses the Amazon states, the cattle census grew by 22% in a decade, compared to the 4% average for the rest of the country, according to an investigation by journalist Gustavo Faleiros for InfoAmazonia and Diálogo Chino.

The data shows that part of this rapid growth in livestock farming is explained by the fact that the sector has become a powerful driver of deforestation. A report by the Trase Initiative, a consortium of researchers studying the impact of commodities, showed that beef exports generate deforestation of 65,000 to 75,000 hectares per year in Brazil. Of that total, 22,000 hectares were attributed to exports to China, the leading buyer of Brazilian meat today.

This change in land use and fragmentation of ecosystems, caused by the replacement of forests and vegetation with extensive crops, creates opportunities for the transmission of malaria and other diseases caused by zoonotic parasites, another study from 2000 by four researchers from the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health found.

“In other words, our growing global appetite will stoke populations of the very species best designed to kill us with new viruses”, Georgina Gustin pointedly stated in a story in InsideClimate News.

In one of the world’s most biodiverse regions, where biodiversity loss is as great a challenge as the effects of climate change, defenders of the environment are an invaluable asset.

They are commonly seen by some social sectors as opponents of economic development, when in reality these leaders and communities are protecting ecosystems that already provide fundamental services, from water provision to air quality, to the rest of society. To that list could be added, according to the study by Keesing and colleagues, the possible prevention of transmission of zoonotic viruses.

This indicates that they are often better guardians of this collective heritage than governments themselves, the military or the police.

This text includes reporting by Antonio Paz, Carmen García Bermejo and Rodrigo Soberanes of Mongabay Latam and Gustavo Faleiros and Aldem Bourscheit of Infoamazonia.