Mongabay has obtained a new, high-resolution satellite image of Petroamazona’s suspected pipeline and drilling platforms in the famed Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) block. Obtained from Planet, the image was analyzed by the team at the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) just after Ecuador announced it had begun drilling in arguably the most biodiverse place on the planet.

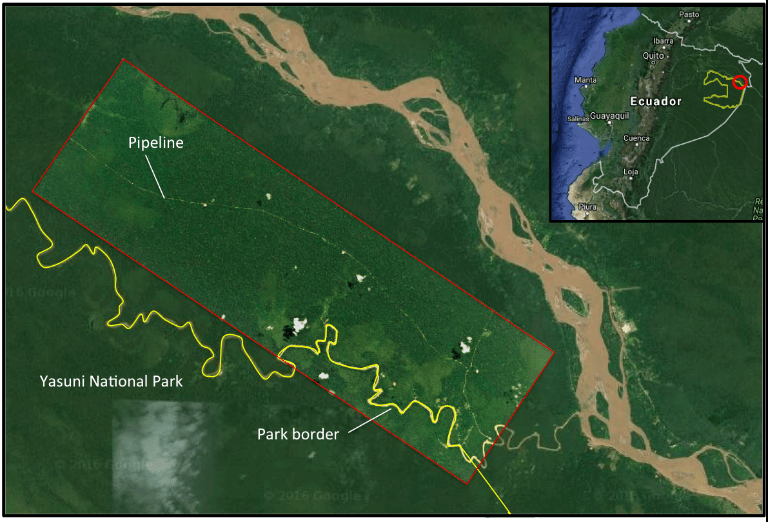

Satellite imagery shows a snaking pipeline amid dense green rainforest that ends in rectangles believed to be oil platforms

by Jeremmy Hance

Mongabay has obtained a new, high-resolution satellite image of Petroamazona’s suspected pipeline and drilling platforms in the famed Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) block. Obtained from Planet, the image was analyzed by the team at the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) just after Ecuador announced it had begun drilling in arguably the most biodiverse place on the planet.

With a resolution of three meters, the image shows a snaking pipeline amid the unbreakable green of the rainforest that ends in rectangles, which are believed to be oil platforms. The picture is especially important given a blackout on outside monitoring of the ITT drilling.

“The government has not allowed any independent monitoring by scientists, journalists, or civil society. The well site is militarized, and aerial flyovers and images are prohibited,” said Kevin Koenig, the Ecuador Program Director at Amazon Watch. “The lack of transparency and independent monitoring are contrarian to any credible due diligence process.”

Low impact?

The Ecuadorean government has claimed the new drilling will impact less than one percent of the Yasuni National Park. But critics contend that this doesn’t take into account any secondary impacts from oil drilling operations, including potentially new roads, infrastructure and an army of oil workers.

“It is well known that building roads into the interior of a national park comprised of rainforest with an abundance of rivers will inevitably lead to colonization, deforestation, game depletion and continuing degradation of the very things national parks are designed to protect,“ Adrian Forsyth, the director of Amazon Conservation Association, said.

Such destruction begins with oil workers infiltrating the region, according to Kelly Swing, the director of the Tiputini Biodiversity Station in Yasuni.

“[The workers] are shown tremendous concentrations of previously unexploited wild game. Subsequently, after they finish their temporary work assignments with oil crews, many come back as hunters.”

Swing added that such activities were “effectively subsidized by oil companies.”

This story has been repeated throughout Yasuni, since vast areas of the park have been exploited for oil development since the 1970s. Oil-exploited areas have gone on to be infiltrated by the usual crews of poachers, illegal loggers and colonizers and have often faced near-constant oil spills.

“Considering that seismic surveys put hundreds of personnel into the forest to carry out noisy activities in a grid pattern every few hundred meters across the entire landscape, we can say that at least 80 percent of the region actually suffers some level of impact,” Swing said.

Critics said that Ecuador could potentially reduce such destruction if it stuck to an inland-offshore oil development model, which would not allow any additional road building to the new oil platforms but instead use helicopters and river transport to reach the well heads.

The inland-offshore model – which basically treats the oil platforms as if they are in the ocean – has been in use in some project in deep rainforests such as the Camisea natural gas project in Peru and the Urucú gas project in Brazil.

“Oil exploitation in Yasuni is a given fact already announced for a long time,” Enrique Oritz, Vice President of the Amazon Conservation Association, wrote to Mongabay in an email. “If modern technology and conditions are applied, the environmental risks may be reduced and/or prevented.”

Oritz added that such a course would require “full transparency,” but that to date has not happened.

But the inland, offshore model is considerably more expensive than more traditional, road-dependent models and several experts interviewed believed that Petroamazonas was making no effort to maintain ITT blocks as a strict inland offshore project. Skepticism is further driven by the fact that the Ecuadorian government allowed Petroamazonas to build a massive road into the adjacent Block 31 even though it had pledged no oil roads there. The government refers to this road as an “ecological trail,” but it’s a trail that can fit several large bulldozers side-by-side.

Even an inland, offshore operation can have significant impact, according to Koenig. He points to Block 10 as an example where Petrozamazonas employed helicopters and a monorail to bring materials in-and-out of drilling sites.

“Twenty helicopter flights a day scared away wildlife, and the break in the canopy from the monorail and flowlines – albeit smaller than a road – was enough to keep animals away.”

Eventually, colonists came anyway, following the monorail that had been cut through the jungle.

“There has yet to be an example of responsible oil extraction in the Amazon,” Koenig said. “In places that are so ecologically fragile and culturally sensitive as Yasuni, even best industry practices—if followed—would not properly protect the forest and its peoples. Yasuni is a place that should simply be off limits to drilling.”

Uncontacted tribes

Perhaps the most damning criticism of the oil operations – even an offshore inland model – is that it further infringes on land held by indigenous tribes that have chosen to remain isolated from the outside world.

Deep in Yasuni live the Tagaeri and Taromenane tribes, a part of the larger Waorani indigenous groups. The Tagaeri and Taromenane tribes only remaining uncontacted indigenous groups in Ecuador. The isolated groups have met outsides with violence, including spearing illegal loggers and other Waorani to death.

Petroamazonas push into ITT not only potentially puts at risk its workers, but also the Tagaeri-Taromenane. The tribes, which may only number a few dozen in total, are hugely vulnerable to common disease with which they have had little contact and therefore developed little immunity. Mortality rates after contact have been known to wipe out half of whole communities and experts fear that pushing oil deeper into Yasuni could result in the total extinction of these two tribes.

Oritz said that while he thought the environmental impacts of oil exploitation “can be prevented to minimized” the same was not true of “the social and cultural issues.”

“Those are more dangerous than environmental ones,” he added.

Oil addiction

Yasuni’s ITT block is arguably the world’s most controversial oil drilling site as the wells will sit directly in what scientists believe is the most biodiverse place on Earth.

“Based on all reliable estimates, well over 10 percent of all species on the planet live here,” said Kelly. “This represents a truly unique opportunity to save a huge proportion of the planet’s natural heritage as well as a daunting responsibility.”

Research has shown that this area of the world has the highest known diversity of mammals, birds, amphibians and vascular plants. Indeed, it’s often pointed out that a single hectare in Yasuni National Park contains more tree species than are native to the U.S. and Canada combined.

In a bid to protect ITT, Ecuador proposed a radical idea in 2007. It would forgo drilling in Yasuni’s ITT block (though it continued to drill across much of the rest of the park) if the international community pledged $3.6 billion (about half of the then expected revenue) to a United Nations Development Program-run fund. The ITT Initiative, as it was called, was billed as a way to protect biodiversity, combat climate change and safeguard indigenous populations. But in 2013, Ecuador abandoned the program citing that it had only raised $330 million or nine percent of the total.

Ecuador has become hugely dependent on oil revenue to fund its governmental operations, a dependence that has only become more desperate as oil prices have fallen. Swing said Ecuador’s dilemma is “the same for the entire world.”

“How can we escape from the all powerful, money-driven oil industry that has been so willing to do essentially anything to maintain its grip on the throat of the world by manipulating markets and public opinion everywhere?”

In Ecuador’s case, Swing said the country should focus more on developing and promoting eco-tourism instead of exploiting its protected areas.

“With so many species in so little space [in Yasuni], it is quite obvious that a visitor has the potential to see more species in less time and for less expense that anywhere else on the planet, but no one knows that because hardly anyone, inside or outside the country, has even bothered to check such details and because there has been so little promotion over the years.”

The first wells in the ITT block have been tapped and started producing. Many more are expected to follow.