How much of Brazil’s rising deforestation rate in the Amazon is attributable to the legal process known as Protected Area Downgrading, Downsizing and Degazettement (PADDD)?

Since 2009, however, the creation of new protected areas has stalled, and now Brazil is scaling back some aspects of its protected area network, just as the deforestation rate is inching back up once again.

To be sure, there are a number of factors at play, including the deep recession gripping Brazil’s economy, which makes forest conversion for agriculture more attractive, as well as a push for large-scale infrastructure projects like hydroelectric dams in the Amazon. At the same time, the government is making steep cuts to funding for programs aimed at reducing deforestation and relaxing the country’s Forest Code, which dictates how much forest must be preserved on private lands.

But how much of Brazil’s rising deforestation rate is attributable to the legal process known as Protected Area Downgrading, Downsizing and Degazettement (PADDD)? According to a new study published in the journal Biological Conservation this month, the answer is somewhat surprising.

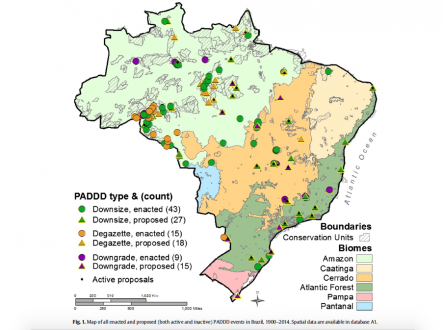

A team led by researchers at the University of Maryland created a comprehensive spatial database and documented all enacted and proposed PADDD events since 1900 to get a sense of how the removal of protected status was impacting forests. They identified 67 enacted PADDD events that affected 112,477 square kilometers (nearly 28 million acres) of land and eliminated 6 percent of Brazil’s total protected areas.

The researchers then compared short-term deforestation rates in areas of the Brazilian Amazon that had experienced PADDD to deforestation rates in areas still under some sort of legally protected status, as well as to areas that had never been protected at all.

“Contrary to previous research, we did not find a significant causal effect of enacted PADDD events on short-term deforestation rates,” the authors of the study write. “[R]ather, short-term deforestation rates in PADDDed forests appear correlated with broader patterns of deforestation.”

University of Maryland’s Shalynn Pack, the lead author of the study, cautioned that her team was restricted by the fact that they only had a few years’ worth of data on which to base their observations of forest change after PADDD was enacted – “that is, 14 of the 19 analyzed PADDD events were enacted in 2010, and our deforestation dataset only extended to 2012,” Pack told Mongabay.

On average, Pack and team were only able to examine changes in forest cover for up to two years after the protected status of any given area was legally changed.

“Since most of these events were enacted due to planned hydropower development, I suspect that there would be a time delay between when the park was legally changed, and when deforestation would begin,” Pack said. “Our analysis was not able to observe these longer-term effects.”

The construction of a new hydropower dam was associated with nearly 40 percent of enacted PADDD events, the researchers found, while rural human settlements were associated with 20 percent.

Another 27 active PADDD proposals would eliminate an additional 60,555 sq. km. (nearly 15 million acres) of protected lands.

“To understand the full spectrum of effects of PADDD on deforestation and land use, we really need longer term study — we need to know how these areas have changed ten or more years after PADDD,” Pack said. “We hope our study can act as a first step towards monitoring and understanding these effects, and hopefully, preventing deforestation in the first place.”

The researchers said that their findings about the impacts of PADDD on the deforestation rate — or lack thereof, at least in the short term — could help guide conservation efforts in the future.

Brazil has set clear policies for the creation of protected areas: establishing a new park requires consultation with the public and technical studies of the social and environmental impacts. But once the park is created, it can be changed, weakened, or even eliminated through a relatively simple political process, without requiring study or public notice, Pack said.

“Many PADDD proposals that are signed through Congress or state governments simply list the new park boundaries in latitude and longitude coordinates, with no map or spatial explanation of the extent of the changes, nor study of the impacts,” she added. “For this reason, PADDD has occurred ad hoc and sporadically, and the public is often left unaware of the changes until they are enacted.”

Any proposal to alter a protected area should require study and explanation of the impacts, as well as public discourse and involvement — “the people have a right to be involved in the future of their natural heritage,” Pack said.

“We hope that our research can drive conversation on PADDD so that governments and the public can make well-informed, unified decisions on the future of their natural areas. We should manage our parks within a tapestry of the protected area network — otherwise, as we keep pulling out threads, the whole quilt may start to unravel.”

– This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.