Martín von Hildebrand is one of the most extraordinary conservation leaders you may have never heard of, he has spent nearly all of his adult life working for indigenous rights and conservation in the Amazon.

Martín von Hildebrand is one of the most extraordinary conservation leaders you may have never heard of. A nationalized Colombian and founder of the non-governmental organization Fundación Gaia Amazonas, von Hildebrand has spent nearly all of his adult life working for indigenous rights and conservation in the Amazon.

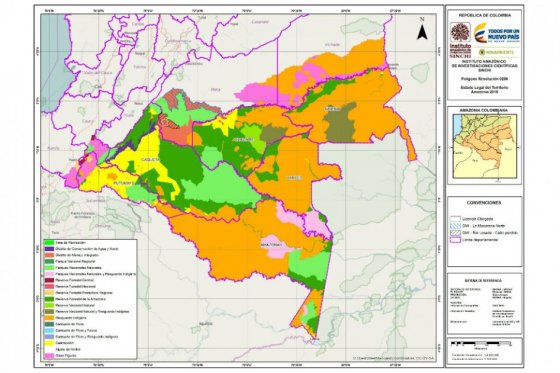

At present he’s helping spearhead one of his most ambitious endeavors yet: establishment of the world’s largest ecological corridor, stretching from Colombia across Venezuela and Brazil to the Atlantic Ocean. Partnering with indigenous communities, national governments and others in the northern Amazon region, the project — dubbed “The Biological Corridor Andes-Amazon-Atlantic” — aims to safeguard 333 million acres (135 million hectares) of forests. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos will present the proposal during the upcoming COP 21 negotiations as a way to address climate change by limiting deforestation. Nearly 80 percent of the corridor already exists as a patchwork of protected areas and indigenous territories, so bringing this project to fruition — as daunting as it might be — isn’t beyond the realm of possibility.

For his work on this and other projects across the Amazon, The Swedish Tällberg Foundation recently named von Hildebrand one of five inaugural Tällberg Foundation Global Leaders and a finalist for its Global Leadership Prize, an award that recognizes “effective, courageous, innovative and values-based leadership.” The two winners of the prize will be announced in Stockholm on November 11, 2015. Ensia recently had a chance to speak with von Hildebrand from his office in Colombia.

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

Todd Reubold Interviewer

First off, congratulations on being named a Tällberg Foundation Global Leader.

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

Thank you. I have a very high esteem for the Tällberg Foundation, so for me, it is a great honor. I feel humbled.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

The award recognizes your work on conservation and indigenous rights in the Amazon. Was there a moment you can point to now when you thought, “This is going to be my life’s work?”

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

There were perhaps several moments, but I think the one that made the biggest impact on me was when I went down to the Amazon as a young man in a canoe on my own for about three or four months. I was meeting other cultures and I was fascinated. I felt I was back in the 16th or 17th century because nobody [I met] could speak Spanish. They were still all living their traditional way and I was miles away, weeks away from any connection to the Western world.

Then suddenly I would run into rubber camps where the indigenous people were being forced to work from 3:00 in the morning until 10:00 at night. They had been there for years and their parents before them as forced labor. I wasn’t expecting to see this. Suddenly something hit me deep and I thought, “God, is this the culture I belong to that can do these things to these people?” I really was ashamed of Western culture. And so I said, I am going to give them a hand to stop the pressure, to stop the encroachment in this way and open a space for them to be themselves, recuperate their land, their culture, to rescue their kids from these boarding schools they were taken to forcefully.

That was the turning point when it really caught me that I’m going to fight for their rights and stop the West from denying them, from imposing on them.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

Throughout your career in government and the NGO sector, you’ve helped indigenous communities across Colombia take back control of millions of acres of Amazon rain forest. As a consequence, the environmental management and conservation of those lands is now in the hands of the indigenous population — a strategy that often results in greater protection of fragile ecosystems. Can this model of indigenous oversight be replicated in other parts of the world facing similar challenges?

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

Yes, definitely. If we want to replicate what we’ve done, we have to start with ourselves. Our Western culture denies other cultures, and it denies space for other cultures. It also has declared war on nature by destroying it. So undoubtedly I would say that what we’ve managed in the Amazon is very important because we’ve developed deep connections with the indigenous people and they’ve shared traditional knowledge. They can sit with the outside world, anybody from the government, whoever it is, and talk in equal terms with absolute self-confidence.

Indigenous people and indigenous cultures will not disappear from the planet if we value them, if we give them importance. But if we continue to deny them and we have more technological power, we’ll slowly undermine them and they will disappear because we make them disappear. They will not disappear on their own, so it is up to us. We are responsible to treat them as equals, to treat them with respect.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

Is there a challenge in reconciling Western and indigenous worldviews in the Amazon?

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

I would say the Western world sees a separation from nature and the human being, and nature is there for us to use and exploit. Most indigenous cultures believe they are part of nature, that they come from nature, and that they have to take care of the whole, which is nature, if they [are] to survive. They are much clearer in their relationship as part of nature.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

What is the most important lesson you’ve learned from the indigenous communities you’ve worked with?

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

I’d say what I’ve learned is that all of us have evolved for so long as part of nature and we developed an intimate relationship. Not only a knowledgeable relationship with the environment, but an intimate, sensual, skin-deep feeling as part of nature.

In the Western world, we’ve been living for the last 100 years or more in towns and in boxes of cement. We have separated from nature. Therefore, we’ve lost our intimacy. But it’s there under our skin; it is alive.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

What is the biggest challenge facing the Amazon in the areas where you’re working now?

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

Our main problem right now in the Colombian Amazon is illegal mining. The countries in this region don’t have many institutions and ways of controlling it.

Right now we are pushing for an enormous [ecological] corridor to go right across the Amazon from the Andes to the Atlantic. We cannot say “hands off.” We cannot make this an enormous protected area. We have to look at those areas where there already is something like oil, or like agriculture, or like cattle ranching and approach it from a sustainable point of view.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

Given the intense pressure from mining and resource extraction, how likely is it the corridor will succeed?

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

I am convinced it is going to work. But it’s not just a protected area. We’re not creating a park. It’s a laboratory. We are creating a laboratory for developing responses to climate change with both indigenous and Western knowledge.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

As you know, ecosystems don’t follow political boundaries. Given your experience working across international borders, what advice would you have for someone in a similar situation?

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

Well, that is a difficult one. The first thing I would say, we have to start bottom up and get the local people fully involved. And that is not only communities, but also municipalities and local organizations, be it environmental or others.

Number two, we have to get the countries to more or less pull their acts together in that territory. Because when you have countries get involved with one another, you can have an agreement, but nobody can go over to another country and say, “You aren’t doing your job.”

Another point is to recognize differences between countries. Some are more developed than others, some have better institutions, and some have better technology. It is important to help the ones that are poorer in their institutions and technology come up to the level to be able to collaborate with the others.

Interviewer Todd Reubold

You’ve been living and working in the Amazon in Colombia for four or five decades now. What’s the biggest positive or negative change you’ve seen in that time?

Martín von Hildebrand Interviewee

For me it’s positive. We’ve passed laws to protect indigenous rights at the constitutional level. We’ve secured international agreements. The indigenous people have set up their own governments. We secured 260,000 square kilometers [100,000 square miles] as indigenous territories. That’s about the size of the United Kingdom.

We’ve changed the history of the Amazon, absolutely changed the history of the Colombian Amazon. With the corridor we’ll change the history of the Amazon. The indigenous people of the Amazon are making it happen. So it is very positive in that sense.

– This report was originally published in Ensia and is republished by an agreement to share content.