The expansion of the Inga people’s Yunguillo Indigenous Reserve was first requested in 1983, but after 20 years of struggles, the efforts of those involved finally paid off as the reserve was quintupled from its original 4,320 hectares to 22,395 hectares.

A landmark achievement was celebrated in southwest Colombia in May when the Colombian Institute for Rural Development approved the expansion of the Inga people’s Yunguillo Indigenous Reserve. The expansion was first requested in 1983, but after 20 years of legal, administrative and infrastructural struggles, the efforts of those involved – including conservationists, human rights activists and indigenous communities – finally paid off as the reserve was quintupled from its original 4,320 hectares to 22,395 hectares.

Twenty-seven percent of Colombia – more than 30 million hectares – is designated as collective indigenous territory. The Yunguillo Indigenous Reserve houses many sacred sites for the Inga people and its expansion protects the headwaters of the Caquetá River – a major tributary of the Amazon River whose watershed covers 250,000 square kilometers.

The decision to expand the reserve shows significant progress in the implementation of legislation from 2009 that safeguards at-risk indigenous communities’ claims to their traditional lands. The Inga tribe of the region will, thanks to the expansion of the reserve, now have increased protection and additional rights to their territory, which is increasingly threatened by mining concessions and other development projects. The reserve’s expansion is credited to the coordinated efforts of the Inga community of Yunguillo, its four communal councils, the national institute for rural development (INCODER), regional indigenous organizations, and the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT).

“This represents a huge victory, not only for the Inga communities, but for the protection of one of the world’s most biodiverse areas,” ACT co-founder Liliana Madrigal said in a press release. “The expansion connects Dona Juana National Park and Serrania de los Churumbelos National Park and secures an important piece of the Andes-Amazon-Atlantic Corridor proposed by President Santos.”

The Yunguillo reserve is also home to species like the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus), the Endangered mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque), the Critically Endangered Colombian woolly monkey (Lagothrix lugens), the jaguar (Panthera onca), and many species of birds including parrots, toucans, and woodpeckers.

According to ACT, the Inga people consider Yunguillo their ancestral territory, making the recognition of their right to this land especially important. The reserve’s expansion helps the Inga people strengthen and engage in traditional customs based on their Laws of Origin and Higher Laws. The Yunguillo reserve and its neighboring reserves encompass an important area of environmental connectivity between national parks. The region consists of paramo – high, treeless plateau – and montane ecosystems, and includes the headwaters of two very important Amazonian tributaries – the Putumayo and the Caquetá.

Expanding a reserve in an area of high ecological value “will contribute to the conservation of habitats for many species of wildlife and promote the transit of species between interconnected habitats, which, considering that the Amazon Piedmont is one of the most susceptible regions to climate change, is a crucial factor in the ability of species to adapt to changes and pressures on the environment,” ACT Putumayo Coordinator, Maria I. Palacios Noguera, told mongabay.com.

Climate change isn’t the only threat to the region. More cocaine is sourced from Putumayo than from any other single site in the world, making the region rife with armed conflict. In addition, Putumayo is economically strategic, as it contains one of the country’s major oilfields. However, despite it all, Inga communities has managed to maintain their way of life, preserving festivals, traditional medicinal practices and their indigenous language. According to the ACT, Indigenous Reserves are the most well-conserved parts of Colombia. Given that community management of natural resources like forests requires a significant amount of communication with and between multiple stakeholders and decision-makers, it is worth noting that 100 percent of the Inga community in Yunguillo has received a bilingual education, setting itself up as a linguistic reference for other Inga communities in Caquetá and Putumayo. In these cases, ACT’s Colombia Director Carolina Gil told mongabay.com, culture is the basis of local work being developed in the community. In recent years, women have taken leadership roles in local education and politics, transforming the nature of the relationship between the Inga community and the Colombian government to one where the concerns of the community regarding their environment are heard.

A 2014 report jointly issued by World Resources Institute (WRI) and Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI) found that land held by local communities and indigenous people tends to be significantly less impacted by deforestation than land managed by governments or private entities. Legally recognized community-managed forests amount to 513 million hectares globally, representing an eighth of the world’s forests. Many communities rely on forest resources for food, water, medicine and building materials. The report attributed the health of community-managed forests to the vested interest members have in sustainably using them. President and CEO of WRI, Andrew Steer said, “What we find is that where there is legal recognition, and where that recognition is protected, enforced, then you have a very, very sharp reduction in deforestation.”

The legal protection Colombia grants to indigenous territories shields them from being sold to third parties, as well as being leased out or held as collateral for any debt. Additionally, the communities themselves manage their territories through traditional methods of hunting, fishing and small-scale agriculture, and through laws and internal rules of coexistence among members of the community as an element of balance with the natural world they inhabit.

“Regarding the management of mining and other proposals in their territories, such as mega development projects, roads, electrification and others, the Inga Yunguillo community have [sic.] opposed the construction of major roads in recent years,” Gil said. To enforce their rights, they have mobilized to block main roads and refused to answer consultation processes. “With the expansion of the reserve, the council led by its governor has proposed finishing a tertiary road, which will enable the community to address their basic needs such as access to basic public services, communication, health, education and marketing of agricultural products.”

While mining activities are, so far, “purely traditional,” according to Gil, the council has refused the various proposals by private sector interests to explore and survey the area.

“Land expansions are an effective tool to combat the various pressures surrounding protected territories. Nonetheless, indigenous communities, in particular the Inga of Yunguillo, are the most vulnerable actors in the face of development pressures, armed conflicts, and institutional weakness, all of which still persist to this day in the Yunguillo region,” Noguera said. The expansion of the reserve also ensures that population pressures from the 1,444-strong Inga community are dissipated over a larger area and that the community has sufficient territory for the development of their Life Plan – the most effective measure to guarantee the community’s survival – which they are currently working on updating to include proposals on self-governance, land and sustainable living and activities in the territory.

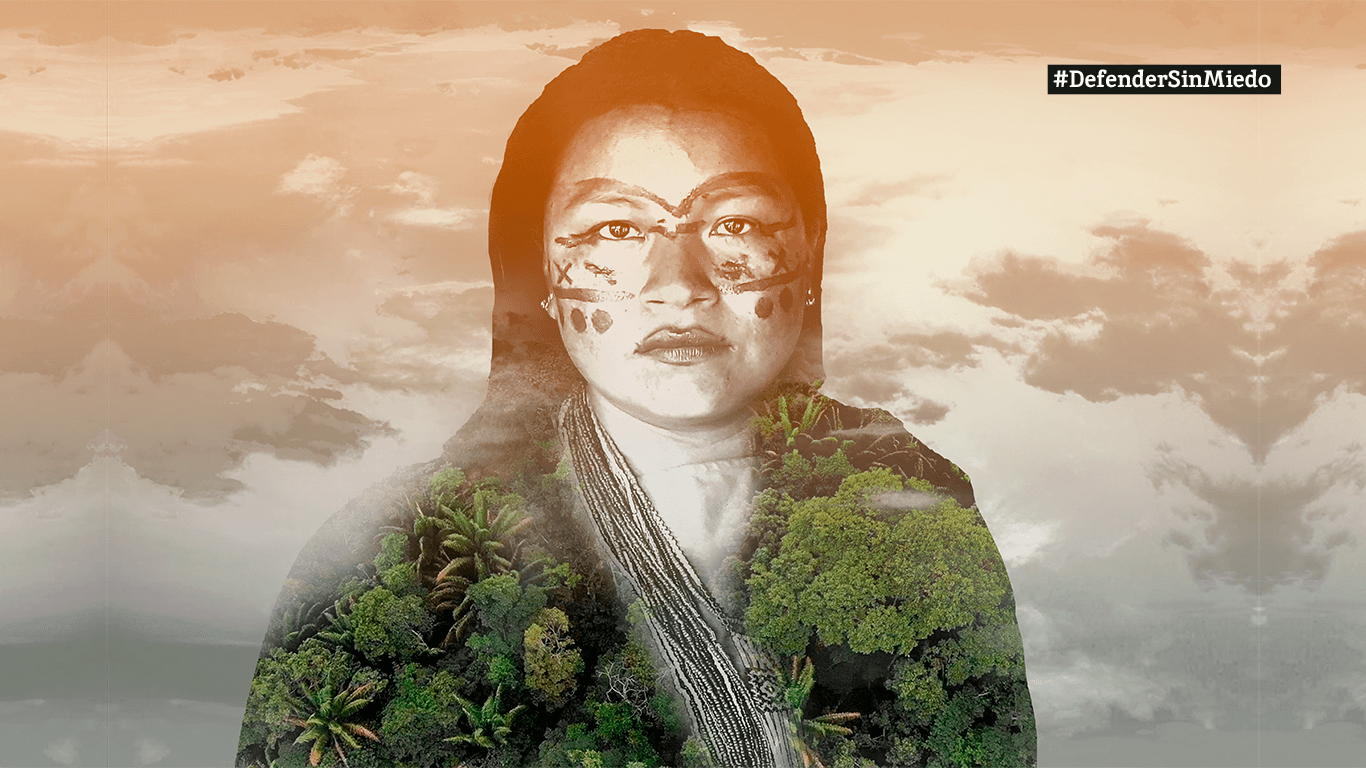

To Nydia Becerra Jacanamejoy, governor of Yunguillo, this land is intricately tied to Inga identity and she maintains the Inga are equipped to protect it.

“We consider Mother Earth to be both the reason for our existence and our reason for surviving,” Jacanamejoy told mongabay.com. “To use the land and its resources properly and respectfully, we observe the traditions passed down over generations. We maintain our identity by maintaining these traditions, while adapting to new conditions in order to protect our territory. We do not believe that identity is possible without territory or that we can protect these lands without a strong sense of collective identity.”

– This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.