Salt marshes of Salicornia plants, a petrochemical plant and a natural gas refinery in the Ashtum El Gamil protected area on Lake Manzala in Port Said, Egypt. Illustration by Simon Toupet/Mediapart with photo by Mohammed Awad, Daraj/Ozone

These are some of the most precious and fragile protected natural areas on the planet. The Great Barrier Reef in Australia with its multicolored fish. The Maya Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala, the largest rainforest in Central America, home to jaguars, monkeys, and crocodiles. Or the Lower Ogooué marshes in Gabon, a refuge for endangered species such as elephants and hippos.

These biodiversity sanctuaries have one thing in common: while they should remain free from all industrial activity, they are peppered with oil and gas infrastructure. There are many more such areas, the “Fueling Ecocide” investigation conducted by 13 international media outlets and coordinated by the Environmental Investigative Forum (EIF) journalists’ collective and the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) media network now reveals.

In this one-year project, we compared 315,000 areas listed in the World Database of Protected Areas (WDPA) with geospatial data for 15,000 oil and gas licences in 120 countries, shared with us by industry provider Mapstand. Our investigation unveils the true extent of the threat that oil and gas companies, including European majors like Shell, ENI and TotalEnergies, pose to biodiversity worldwide.

A global overlap with protected areas bigger than France

According to our analysis, 3,164 oil and gas production and exploration permits encroach on 7,021 protected areas located in 99 countries. This represents a total of more than 690,000 km² handed over to oil companies, an area bigger than the size of France. In some cases the overlaps are partial but half of these protected areas are entirely covered by hydrocarbon licences.

Areas crucial to the future of the climate are at risk, such as the rainforests of the Amazon, the Congo Basin and Indonesia, various mangrove forest reserves scattered in Tanzania, Guinea-Bissau or Malaysia as well as key marine protected areas, including Europe’s North Sea.

Only a small part of these 690,000 km² overlapping with protected areas are actually covered by oil and gas facilities on the ground. But all these encroachments represent an actual or potential threat to biodiversity. Leave it in the Ground (LINGO), an NGO which has published numerous reports on the subject called for “an immediate ban on fossil fuel exploration and extraction in protected and conserved areas globally”.

Exploration licences cover 387,000 km² of protected areas, more than the size of Germany. These permits can already contain infrastructure and exploration wells. In marine protected areas, technologies used to map the undersea deposits, harming various forms of marine life in the process, can be deployed.

Then come the permits whose status is not available in our data. And finally, the overlaps of oil and gas production licences, the ones creating the biggest risk, are still almost as big as Ireland, covering 74,000 km² of protected areas.

Impressive as they may seem, these numbers are underestimated, as the data for 16 countries, including important oil producers like Canada, Iran and Venezuela, was inconsistent and was not included in the analysis.

Read the detailed methodology here.

Air, soil and water pollution, deforestation, harm to endangered species: in many cases, destruction is already underway, as documented by NGOs and observed on the ground by reporters of Daraj and InfoCongo, members of the “Fueling Ecocide” project.

In Tunisia, the sea is polluted by oil leaks from offshore platforms in the protected area of the Kerkennah Islands, a wetland of international importance protected by the Ramsar Convention. Also known as “The Convention on Wetlands”, the Ramsar Convention was adopted in 1971 by almost 90% of the UN member states, providing the framework for conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources.

In the Republic of Congo, part of the Tchimpounga reserve, a sanctuary for Central African chimpanzees, is being transformed into an industrial zone due to a potash mine and an oil well drilled by Chinese companies. “The ecological balance is threatened: wildlife is retreating to less protected areas, the soil is becoming depleted, and waterways risk being polluted”, says Placide Kaya, a Congolese forestry engineer and environmental activist.

The ecological balance is threatened: wildlife is retreating to less protected areas, the soil is becoming depleted, and waterways risk being polluted.

Placide Kaya, a Congolese forestry engineer and environmental activist

In Iraq, five oil fields owned by major companies such as TotalEnergies, ENI, BP, and CNPC are contributing to the drying up and pollution of the protected and once lush wetlands in the south of the country. This has had dramatic consequences for the environment and wildlife, as well as for the local population, who can no longer make a living from fishing and livestock farming. Αccording to Fueling Ecocide partner Daraj, the situation has worsened since the arrival in 2023 of the Chinese oil company Geo-Jade, whose operations are encroaching on the Hawizeh wetlands, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

It is mainly areas internationally recognized as being the most crucial for the planet that are massively affected. Οur data shows that two-thirds of the global encroachments’ surface is located in approximately 6,300 internationally recognized protected areas: UNESCO and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) sites, Ramsar wetlands, Indigenous lands and Natura 2000 areas of the European Union. The remaining affected areas are under national protection status only.

The IUCN and UNESCO recommend a ban on oil and gas activities in their protected areas. The IUCN has approved a resolution committing to not authorize hydrocarbon activities in the protected areas on its list, but this is not legally binding. A July 2025 report by UNESCO shows that there are oil and gas licenses and bid blocks in a quarter of the sites that this United Nations agency has inscribed on the World Heritage List.

“World Heritage sites cover less than 1% of Earth’s land, but harbour one-fifth of global species richness”, a UNESCO spokesperson told us. Hydrocarbon production in these areas could provoke “irreversible environmental damage, undermine local livelihoods, erode the unique qualities that earned these sites global recognition […] and jeopardize global biodiversity targets”, the spokesperson added.

Scientists warn that a “mass extinction” of living species is ongoing. And as fossil fuel combustion remains the main driving force for global warming, biodiversity loss “exacerbates the effects of climate change”, said the Scientific Council of the COP15 on Biodiversity organized by the United Nations.

Oil extraction in protected areas contradicts the ambitions of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) adopted at COP15 by 196 countries in 2022. The GBF set the objective of protecting 30% of the surface of the planet’s seas and lands by 2030, compared to 17.6% and 8.4% respectively today.

“The Global Biodiversity Framework treaty is international law. The great failure of this treaty is that there’s no enforcement mechanism. Unlike the Paris Agreement [the international treaty aimed at combatting the climate crisis] which can include fines. In this case, it is problematic for the ecosystems. Yes, it’s a huge problem”, explains Stephen Woodley, ecologist and consultant for the IUCN. “The enforcement of international environmental law remains weak: responsibility falls on individual states”, adds Antonio Tricarico of the NGO ReCommon.

The Global Biodiversity Framework treaty is international law. The great failure of this treaty is that there’s no enforcement mechanism. Unlike the Paris Agreement which can include fines.

Stephen Woodley, ecologist and consultant for the IUCN

In this context, the hydrocarbon companies can easily evade their environmental responsibilities. “The very value of oil companies is based on their ability to secure future production assets. This growth logic is intrinsically incompatible with the ecological transition”, says Tricarico.

Oil majors: Pledges falling short

Our investigation shows that 763 different oil companies operate at least one permit that overlaps with a protected area. We ranked them according to surface area size, considering only production licenses.

Four of the major international companies that appear in our top 10 list are European. Anglo-Dutch Shell occupies third place, mainly due to its offshore fields located in protected areas of the North Sea. It is ahead of the French Perenco (5th) and TotalEnergies (7th) and the Italian ENI (9th).

Several companies in our top 10 including Perenco, Energy Development Oman and the Emirati company Adnoc do not enforce any “no-go” policy. In their annual reports, Shell, TotalEnergies, and ENI only commit to not operate in UNESCO sites, and therefore allow themselves to drill in all other protected areas.

Even this minimal promise is not always kept. Shell operates assets overlapping with two UNESCO World Heritage sites: the Great Barrier Reef in Australia and the Wadden Sea in The Netherlands. Contacted, Shell declined to comment.

TotalEnergies also holds shares in a LNG plant in the Great Barrier Reef while ENI has an exploration licence located inside a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve: the Marawah Marine Protected Area in the United Arab Emirates, which covers 4,249 km². This archipelago of a dozen islands, surrounded by coral reefs and dotted with mangrove forests is home to the world’s second-largest colony of dugongs, an endangered marine mammal. Commercial gas extraction has not yet begun, but exploration for new wells is already well underway and ENI announced the discovery of a significant deposit in 2022.

The national Emirati oil company Adnoc, 4th in our ranking, operates three oil and gas licences in the same area. One of them, Gasha, one of the biggest hydrocarbon projects in the world, covers one quarter of the Marawah reserve. Currently under construction, the huge project includes 11 artificial islands, wells, pipelines and shipping docks. “We operate under stringent environmental controls and have a proven track record of safeguarding nature and biodiversity”, Adnoc answered us.

Read Adnoc’s full reply here

None of the companies publish geo-data that could allow verification of their activities in protected areas. Publicly traded majors Shell, ENI and TotalEnergies publish a list of their overlaps. For these three majors, we discovered cases of non-reported licences intersecting with protected areas.

ENI, which reports only operated licences, lists 32 overlaps in its 2024 annual report, while our investigation identified 68 operated licences that intersect with protected areas.

TotalEnergies reports 12 upstream operated and non operated projects overlapping with protected areas, which corresponds to 28 licences according to our calculations, whereas our analysis identified 69 of such TotalEnergies licences overlapping with protected areas.

The main explanation for these missing overlaps is that the companies don’t take exploration licences into account and only report their activities located inside some internationally recognized areas, including UNESCO, Ramsar and IUCN categories 1 to 4 – despite IUCN recommending that there is no industrial activity also in the less sensitive categories 5 and 6.

ENI replied that part of the difference is also due to its methodology, which excludes hydrocarbon producing facilities which do not “effectively fall within the area of intersection with a protected area”.

Read ENI’s full reply here.

However, ENI implicitly acknowledged the absence of detailed disclosure, noting that “the ESRS E4 ‘Biodiversity and Ecosystems’ standard requires the communication of information at an aggregated level. This means that reporting does not require the description of each individual asset or concession”.

When asked about non-reported overlaps, Shell again declined to comment.

TotalEnergies adopted the same methodology, and replied that our figures “don’t reflect the reality on the ground”, as they correspond to the “theoretical intersections of licences with protected areas, despite the fact that only a small part of the surface of these licences is covered with infrastructure”.

Read TotalEnergies’s full reply here.

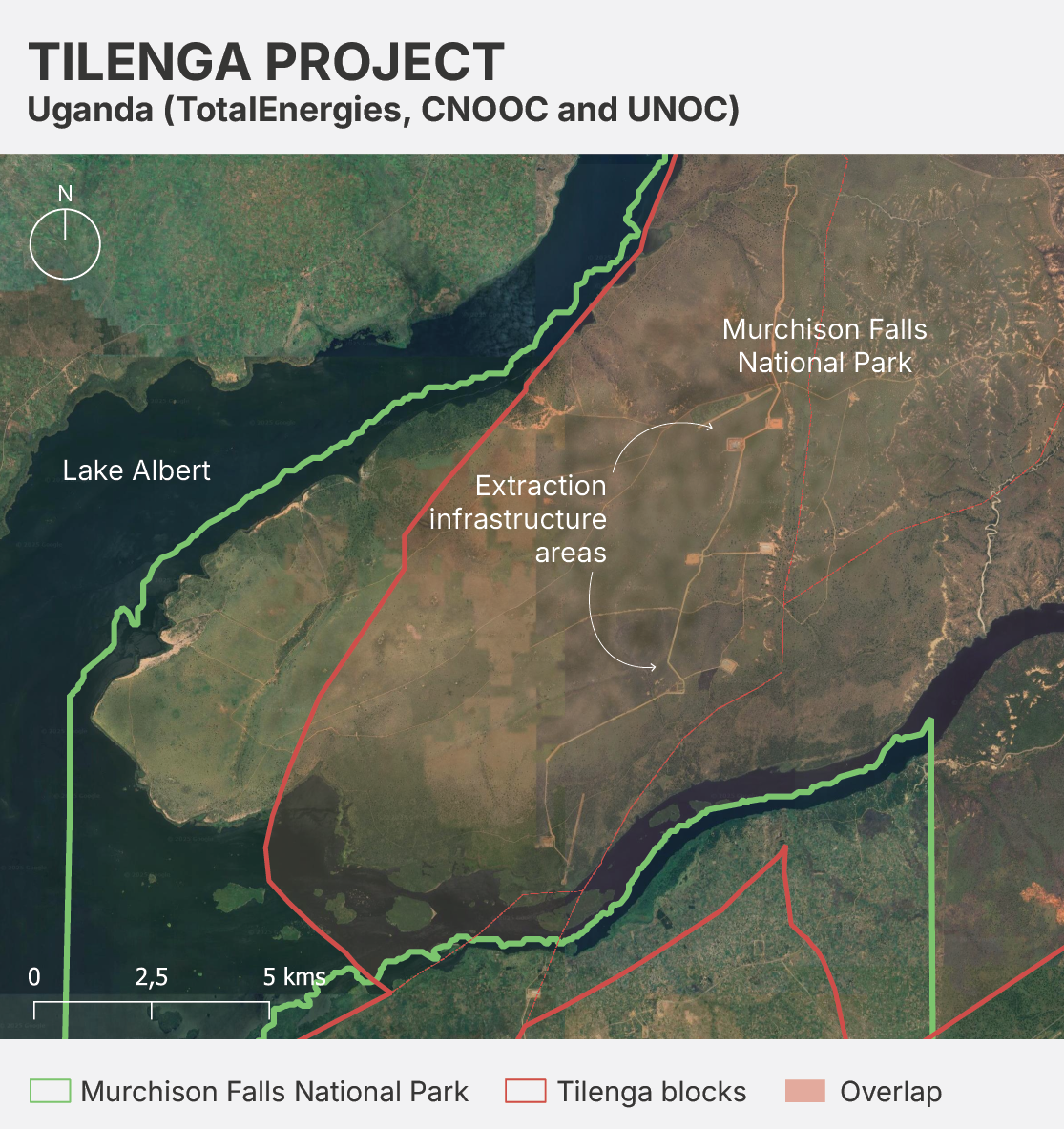

In Uganda, near the shores of Lake Albert, TotalEnergies, its Chinese partner CNOOC and the national oil company of Uganda UNOC own the Tilenga and Kingfisher licences, a huge oil project coupled with a 1,443 km pipeline called EACOP. Construction works on the ground are well advanced and production is due to start in 2026.

Tilenga, operated by TotalEnergies, is located largely within Murchison Falls National Park, an exceptional IUCN and Ramsar site, home to more than 140 species of wild mammals (antelopes, lions, elephants, hippos, giraffes, etc.), some of which are threatened with extinction. The project is heavily criticized by several environmental NGOs, which have sued TotalEnergies in France for alleged ecological damage – the company denies the claims.

According to our data, Tilenga’s licenses cover 10% of Murchison Falls National Park, or 373 km². TotalEnergies claims that its infrastructure encroaches on only 0.03% of the protected area – just 1 km². The group states that it takes into account “the physical footprint of the facilities and their area of influence”, but refused to explain its precise methodology to us.

Satellite analysis conducted for the “Fueling Ecocide” project by the NGO Earth Insight shows that TotalEnergies’ figures seem to correspond only to the surface of the drilling pads. But according to Earth Insight, 38 km of roads and 20 km of pipeline infrastructure have also been built inside Murchison Falls, cutting the northern part of the national park in two.

A field investigation, published in September 2024 by the NGOs Afiego and Friends of the Earth, concludes that the project’s negative impact on wildlife is far exceeding the immediate perimeter of TotalEnergies’ facilities. The report indicates that elephants, disturbed by the vibrations and noise from the construction works, are “destroying farmland” and have killed five people between June 2023 and April 2024. Meanwhile, light pollution from the drilling platform, visible up to 14 kilometers away, reportedly has negative impacts on nocturnal predators such as leopards, lions, and hyenas.

Asked by EIC, the NGO Lingo said oil companies only count infrastructure surface in their methodology in order to “confuse and downplay their negative impacts”, as “it seems that they are not accounting for the liquid, gaseous and solid pollution that their facilities are producing and bringing to surrounding areas”.

The same applies to marine protected areas where damage can extend far beyond the small surface covered by offshore platforms. “Extracting oil and gas in these protected areas is a complete aberration”, says Sara Labrousse, a marine ecology researcher at the CNRS, the French National Center for Scientific Research. “It has very harmful consequences, including oil spills, as well as underwater noise and ship traffic, which create enormous disturbances for marine species”.

Oil companies almost never give details about the impact of their operations on the ground. In their annual reports, Shell, ENI and TotalEnergies write that they implement biodiversity action plans (BAPs) in protected areas, aiming for “no net loss” or even a “net gain” of biodiversity. However, they are the ones who pay the consulting firms that draft the BAPs, and these documents are not made public. In the case of Tilenga, Mediapart revealed that TotalEnergies intervened to weaken measures included in the BAP, which are insufficient to protect biodiversity.

“TotalEnergies enforces its biodiversity ambitions, whose axes 1 and 2 aim at preserving protected areas. […] TotalEnergies reports every year on how it enforces this ambition”, the company answered us.

“ENI adopts an approach to biodiversity and ecosystem services based on compliance with local regulations and internationally recognized standards, with the aim of preventing and mitigating impacts”, the Italian major told us.

‘Paper parks’: how governments fail to protect

In their responses to EIC, ENI and Perenco pointed out that it is legal to operate in protected areas in compliance with national regulations. This is true and raises the issue of the responsibility of the states which granted these permits. “This is the phenomenon of so-called ‘paper parks’: areas that are designated on paper but lack effective protection in practice”, comments Francesco Maletto, an environmental lawyer specializing in offshore protected areas for the NGO ClientEarth.

This is the phenomenon of so-called ‘paper parks’: areas that are designated on paper but lack effective protection in practice.

Francesco Maletto, an environmental lawyer specializing in offshore protected areas for the NGO ClientEarth

Read Perenco’s full reply here.

Taking into account only production licenses, the most affected country in the world is the United Kingdom. It has issued 120 permits that encroach on 46 protected areas, an overlap of more than 13,500 km², mainly due to offshore exploitation in the North Sea, where TotalEnergies, Shell and Perenco operate. Most UK permits overlap with OSPAR protected areas, a protection regime that allows oil and gas exploitation.

According to investigations conducted in 2023 and 2024 by Unearthed and The Ferret, based on official government data, around 300 tonnes of oil from offshore platforms spilled into British protected marine areas in the last decade. Despite this, the UK government granted 64 new licenses in the North Sea in October 2023, 17 of which were located in protected areas.

When taking into account all types of licences (including exploration) overlapping with internationally protected areas, our top 10 includes mostly countries of the Global South, with the exception of Russia and Australia. Australia tops our ranking with overlaps of 115,400 km².

In Brazil, our partner InfoAmazonia discovered that the government has granted a gas exploration licence covering 75% of the Krenyê Indigenous Land, in the biodiverse tropical savannah of Maranhão state, in the Legal Amazon administrative region. First drilling is expected to begin inside the block in 2026 by the Brazilian company Eneva, according to information published by the company.

The permit was issued in 2017 despite the Krenyê people obtaining an agreement for the protection of this land in 2016, after years of battle, according to a document shown to us by their leader, Chief Cu’tetet. Brazilian law prohibits fossil fuel extraction on indigenous lands and the Krenyê people have not been consulted about the licence.

Contacted, Eneva said that it respected “legal procedures established by the competent authorities”. The Brazilian national petroleum agency told us that the Indigenous area was officially designated only in January 2018, when it had already granted the concession for gas exploration. The Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), the federal environmental agency, said to InfoAmazonia that the area of the gas block that overlaps with the indigenous territory needs to be excluded.

Read Eneva’s full reply here.

Our investigation also shows that poor, autocratic and war-torn countries are willing to offer up huge protected territories to oil companies.

The Central African Republic ranks sixth in our list due to two exploration permits granted in 2013 by former dictator François Bozizé to PTIAL, an oil company controlled by Poly Technologies, a Chinese arms corporation wholly owned by the Beijing government. Αccording to our calculations, these permits encroach on 13,800 km² of seven protected natural areas of exceptional ecological importance, including Bamingui Bangoran National Park and Manovo Gounda National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

During the civil war that followed the overthrow of President Bozizé in 2013, PTIAL financed armed groups in order to continue its operations, according to a UN panel. The license was renewed in 2018 by the new president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra, who consolidated his power with the help of the Russian Wagner Group militia. From 2024, Poly Technologies, PTIAL’s parent company, has been sanctioned by the United States and then the European Union for selling arms to Russia following the invasion of Ukraine.

It is unclear whether preparatory work for the first drilling operation, which was halted in 2018 for “safety reasons”, has resumed. Poly Technologies and the Central African Ministry of Mines did not respond to requests for comment.

The list of threatened ecosystems continues to grow. In the Republic of Congo, the seventh country in our ranking, there are already 20 oil permits encroaching on 13,600 km² of thirteen internationally protected natural areas. The autocrat Denis Sassou N’Guesso has just added a new one: the Niamba permit, granted in April 2025 by decree to the Chinese company Oriental Energy in partnership with the National Petroleum Company of Congo (SNPC).

Congolese NGOs have strongly condemned this decision as the licence encroaches on a sensitive part of the Conkouati-Douli National Park, a triple-protected area (IUCN, UNESCO and Ramsar). Its rainforests harbor the greatest biodiversity in the country including endangered species such as monkeys, elephants and sea turtles.

Hydrocarbon production in protected areas is a global, extremely sensitive political and economic problem, as the world’s richest biodiversity hotspots are overwhelmingly concentrated in the Global South, in tropical forests, coral reefs, and savannahs, while the expansion of oil and gas extraction is largely driven by companies headquartered in the Global North and China.

According to the Global Oil and Gas Extraction Tracker, since 2015 about 22% of new oil and gas resources were discovered in Latin America and the Caribbean, nearly 26% in Asia, 12% and Africa, and only 36% in North America and Europe. InfoAmazonia’s data analysis shows that the Amazon region holds nearly one-fifth of the world’s global reserves identified between 2022 and 2024, establishing a new frontier for the fossil fuel industry.

This geographic asymmetry raises pressing questions about equity and responsibility while the target of protecting 30% of the world seas and land collides with the failure to enforce policies and the insufficiency of corporate pledges.

In the meantime, drilling continues. And natural wonders and endangered species are paying the price.

Reporting by Alexandre Brutelle, Yann Philippin and Daniela Sala

Data & geodata analysed by Leopold Salzenstein, Dafni Karavola, Alexandre Brutelle, Yann Philippin and Renata Hirota (Brazil)

Additional reporting by Hala Nasreddine, Philomène Djussi Fotso and Juliana Mori

Edited by Eurydice Bersi

Website produced by Chris Gioran and Dafni Karavola

This is part of the series “Fueling Ecocide”, developed by EIF, a global consortium of environmental investigative journalists, in partnership with the European Investigative Collaborations network, and their partners.

This investigation was supported by the Journalismfund Europe and by IJ4EU (Investigative Journalism for Europe).