By Plan V*

The Comandos de la Frontera, a Colombian armed group that also operates in northern Ecuador, and the Ecuadorian gang Los Choneros have imposed a regime of terror in the Amazonian provinces of Sucumbíos and Orellana, although the alliances between them are unclear. One of the illegal activities that has grown the most in the region is gold mining, which is rapidly destroying the jungle and rivers like the Punino, a name that has become synonymous with destruction and death.

The waters of this river stand out amid the vast green of the Amazon due to their yellow color, altered by mining activities. The Punino flows between the provinces of Orellana and Napo in northeastern Ecuador, approximately 65 kilometers from the Colombian border and almost 150 kilometers from Quito. From the air, the color of the Punino contrasts with the dark green—almost gray—of a neighboring river, the Payamino. Both have been affected by illegal gold mining in this part of the Amazon, home to Kichwa communities and rich biodiversity.

Changes in Punino and Payamino rivers between June 2022 and May 2024.

Dozens of backhoes operate upstream, in an area known as the Upper Punino, and they are changing nature, the river bed and the social dynamics of the area. Villages that used to be peaceful have seen the number of violent deaths increase in the last two years and have witnessed macabre scenarios, typical of mafias in other countries. The communities are divided over the gold business, and people who were protesting now prefer to remain silent in the face of threats from outsiders who have arrived to take control of everything.

The jungle is also changing. The ‘rapid expansion of illegal mining’ has caused the deforestation of 2,473 acres (1,001 hectares) in the Upper Punino – equivalent to 1,400 professional soccer fields – between November 2019 and December 2023, according to a report released last February by the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP). 78% of the area corresponds to logging recorded in a single year – 2023.

Gold in the Punino is alluvial and it is mixed with sand and clay. The oldest inhabitants of Orellana remember that Kichwa communities always panned gold to make money and buy school supplies or clothing, but without getting carried away by ambition. That is why they call gold supay ishma (Kichwa for “the devil’s urine”).

Now, the indigenous communities settled in the Punino are changing. This is the case of San Lorenzo, with approximately 350 residents, or Santa Catalina, a small village with only 25 people. Before mining started, palm cultivation was the main economic activity in those places. To access them, one must go through San José de Guayusa, a larger village located about 12 miles (20 km) from the Punino mining area, which is under the jurisdiction of the province’s capital Francisco de Orellana, better known as El Coca.

In recent years, outsiders arrived in the area from other parts of the country and from Colombia, bringing illegal mining, destruction and violence.

To extract gold from the Punino, miners use aggressive methods. With backhoes, they move large amounts of earth that will be deposited it in a type z sorter – a machine that separates gold from earth. The change in the color of the Punino waters is due to the presence of sediments that come from the discharges of high-sulfur clay and mud caused by clearing vegetation, moving soils, and washing alluvial gold, explains Matthew Terry, an environmental activist and a member of the Río Napo Foundation.

Mining is a multimillion-dollar business. From the information provided by the authorities after seizing machinery, it can be deduced that each backhoe would cost around US$ 150,000. Between October 2022 and May 2024 alone, the military found 82 backhoes in eight operations in San Lorenzo, Alto Punino, and San José de Guayusa; an investment of over 10 million dollars, not including what is required to buy power generators, water suction motors, and thousands of gallons of fuel, a resource that has also been seized in operations.

The damage to the ecosystem is not caused only by the machines, but also by the use of fuel, oils, lubricants – and mercury. This metal has been banned in Ecuador since 2015, but it is still used in illegal mining activities, even though the Ecuadorian State ratified the Minamata Convention, which seeks to protect human health and the environment from mercury’s adverse effects.

Illegal mining is growing rapidly in El Punino, moving from one area to another and entering the jungle to escape military and police anti-mining operations. “They pass the Yutzupino community and end up here,” says an Orellana resident who has come to the Punino on several occasions to record the advance of illegal mining. Of medium height and tanned skin, he wears a hat to protect himself from the intense sun. He will only be identified here as the guide with the hat since he prefers to remain anonymous to avoid retaliation.

He mentions the case of Yutzupino, a community in Napo, adjacent to Orellana and crossed by the Jatunyacu River, the epicenter of illegal mining after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Anti-mining operations have been carried out in both Yutzupino and the Punino, but people are skeptical about their effectiveness. There are reports of backhoes destroyed and seized, and questions about the machines that were not destroyed or why miners sometimes know about the operations in advance. Then, machines are soon back in operation. In addition, few cases end up in court. Between 2021 and February 2024, the Public Prosecution Service received 23 complaints about mining-related crimes, but only one case has reached the trial stage in three years. Meanwhile, mining areas spread to other places.

The guide with the hat and other social leaders interviewed, who also do not want to be identified, agree that some miners from the Jatunyacu River have moved to the Punino. The two rivers are five hours apart by road. The Punino is a tributary of the Payamino, which connects with the Coca, one of the largest rivers in the Ecuadorian Amazon, which supplies water to dozens of indigenous and mestizo communities.

LOS CHONEROS PREFER AMAZON GOLD

The Amazon Underworld team reached San José de Guayusa. While security concerns prevented them from going to the exact area where mining activities are carried out in the Punino, they were able to observe the consequences downstream. At the junction of the Punino and the Payamino, the waters become bicolor and the yellow of the former and the gray of the latter can be clearly seen.

During the journey last February, the team were able to observe a narrow, one-lane, stone and sand road that connects Guayusa to the Kichwa community of San Lorenzo, the closest district to the mining area. The entrance seemed to be guarded by two men sitting under the shade of trees, who did not lose sight of what was happening around them.

The road crosses palm plantations, which in turn have countless small paths. Although the distance is short, the journey between both communities can take up to three hours due to the poor conditions of the road. These characteristics make it a death trap for those who seek to venture out without permission.

But who authorizes entry through the road where the supposed guardsmen are? Residents and social leaders agree that the gold rush attracted outsiders – groups of Ecuadorians and Colombians. And they would have brought violence with them. Orellana went from being one of the most peaceful provinces in the country to having a high number of homicides. In 2023, it recorded a rate of 29.6 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, making it the ninth most violent province in the country. In 2024 (up to May 19), Orellana climbed to second place with a rate of 25.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC).

Indigenous affected by the illegal minery in Punino River

No mining activity has been recorded in Joya de los Sachas, but the place favors its logistics. Unlike Guayusa, where there is no internet connection or telephone signal, Joya is a larger town with more commercial activity and infrastructure, and less police and military presence. During the day, Guayusa looks desolate because most of the inhabitants work on farms far from the town. Only at midday, when the children leave school, people can be found in the dusty streets.

According to local leaders, Los Choneros – one of the largest and most dangerous gangs in the country – were the first to arrive in Orellana attracted by gold, about two years ago. People describe them as mestizos coming mostly from coastal cities, which can be told by their accent. A citizen who participated in one of the anti-mining demonstrations in El Coca remembers that he met a man who introduced himself as a member of Los Choneros during that event.

On May 1, the Armed Forces reported the arrest of 22 “alleged members of Los Choneros” in San José de Guayusa during an operation against illegal mining. They also seized three firearms, 141 pieces of ammunition, 350 gallons of fuel, and military and police uniforms.

In addition, eleven other alleged members of that group were arrested in Orellana between January and April of this year for illegal possession of weapons, theft and kidnapping, according to police sources. One of the suspects captured had a lion and an eagle tattooed on his chest, with the motto “Brotherhood until death, a joint enterprise.” The lion is the symbol of the group Los Fatales and the eagle represents Las Águilas. Both are recognized as the main factions of Los Choneros.

The three are among the 22 “transnational organized crime groups” engaged mainly with drug trafficking that were designated as “terrorist organizations and belligerent non-state actors” by the government of Daniel Noboa in a January 9 Executive Order. The document acknowledged the existence of a “domestic armed conflict” aimed at tackling the increasing violence in the country and included the military in internal security tasks. Calling them “belligerent” brought criticism to Noboa because they are criminal groups, while that designation could portray them as insurrectionists with political aspirations.

THE ARRIVAL OF COMANDOS DE LA FRONTERA

Los Choneros are not alone in the gold business of the Punino area. Orellana deputy police chief Juan Vinicio Ramos confirmed that Comandos de la Frontera (CDF) –or Border Commandos, a Colombian armed group– are present in the province, although he did not provide details on whether the two groups operate together or about their specific operations. He said that this is a confidential matter being investigated by other police units. He is not the only one avoiding the topic. For several weeks, Amazon Underworld asked for an interview with the military chief of the Jungle Brigade No. 19 Napo, which is in El Coca and organizes the operations in both Orellana and Sucumbíos. But they did not respond to calls or text messages.

Ramos blamed the increase in violence in Orellana on the CDF and Los Choneros and their participation in illegal mining.

There is also evidence of the presence of the CDF in the border Ecuadorian province of Sucumbíos, but their arrival in Orellana shows that they have been entering non-border areas.

The CDF are linked to the Segunda Marquetalia, a group led by former FARC peace negotiator Iván Márquez, who, after signing the 2016 agreements with the Colombian government, went back into hiding.

On June 5, delegations from Gustavo Petro’s government and the Segunda Marquetalia signed an agreement to formally initiate new peace talks and announced the establishment of a negotiating table in Caracas by the end of June. Negotiators on behalf of that group include Giovani Andrés Rojas, alias ‘Araña’, leader of the CDF, who is on the Ecuadorian government’s list of “military objectives in terrorist groups.” ‘Araña’ participated in meetings with the Colombian government and has even appeared speaking about the new peace process.

The CDF operate mainly in the Colombian department of Putumayo, bordering Sucumbíos, and are engaged in drug trafficking, extortion and illegal mining. The group was formed in November 2017 and includes dissidents from blocs 32 and 48 of the FARC, from the criminal gang La Constru, derived from paramilitary groups and even former members of the military.

The Comandos arrived in Ecuador when Araña took control of that organization, a Colombian Intelligence source told Amazon Underworld. According to Colombia’s Public Prosecution Service, Araña was a member of the Los Rastrojos militia, a drug trafficking organization, and he also appeared as a member of the FARC. Under the peace talks, he was appointed as a peace manager in 2017 and left prison to do social work, but he formed the CDF instead.

Araña was borne in Cali but has lived in Putumayo since he was 7 years old. For this reason, says the intelligence source, “he has always operated in Ecuador,” mainly in Sucumbíos. Having been a member of the FARC, he continued to use Ecuadorian territory as a place of rest, training and refuge, as the guerrillas historically did in that area.

The Colombian Intelligence report also confirms that the CDF has weapons, hideouts and drug laboratories in Sucumbíos. He says, for example, that the person known as Galvis is in charge of transporting 1.5 tonnes of cocaine paste every 25 days to Ecuador, where they have crystallization plants to finish processing it.

Residents of Sucumbíos’s capital Lago Agrio refer to the CDF as the FARC and describe them as a “hidden power” that supposedly keeps common crime at bay. “We often hear that these (Colombian) groups protect us from Ecuadorian gangs. Citizens think they are better off like this,” when compared to the disputes and intense violence in other parts of the country, says a local journalist who preferred not to be identified.

Violence rates have also skyrocketed in Sucumbíos in recent years, although they are far from those seen in coastal provinces, the most affected by violence. In this province, violent deaths increased from 27 in 2019 to 176 until October 2023, according to the Ecuadorian Organized Crime Observatory. More than 70% of cases in 2023 were concentrated in the capital Lago Agrio.

In recent years, the CDF have been at the center of several violent episodes in Sucumbíos. They are blamed for killing eight people in January 2022, an act of revenge for the murder of one of their members, an Ecuadorian Police Intelligence source told El Universo. Furthermore, last March, in the border district of Barranca Bermeja, four Ecuadorian military who were on patrol duty were attacked by armed men, which had not happened since 2018. One of them died. Then, in April, soldiers killed one man and captured seven others, including two minors, in a mining camp in San José de Guayusa. A Colombian ID card was found among the belongings of one of the detainees.

General Fernando Adatty, commander of the Army, told the digital media Código Vidrio that the military were searching for a resting place of one of the groups’ leaders in Barranca Bermeja. “In that district there is a route used by the CDF to go to mining areas in Ecuador; they are passageways, resting areas, there is movement of fuel, things that are needed for illegal mining, including transfer of weapons and supplies,” he said.

According to the Colombian Intelligence report, Araña circulates in the town of Santa Rosa de Sucumbíos, on the Ecuadorian side, which is only 6 miles (10 km) from Barranca Bermeja. Other towns that he would visit include San Martín and Villa Hermosa.

The stories told by the military chief and the Colombian Intelligence report coincide with the description of the guide with the hat. He says that these armed groups pass to Orellana on dirt roads. For example, they use the La Bonita-Lumbaqui road, which begins on the Colombian border, passes through Sucumbíos and then reaches a district called Sardinas, in Orellana.

Through that same route, the gold would leave for the neighboring country, as the guide with the hat was told by residents of the Upper Punino area. They would also be using the road that connects Lago Agrio, in Sucumbíos, Ecuador, with La Hormiga, in Putumayo, Colombia. But another part of the production, says the guide, is left to the domestic market because the miners use gold to pay farmers for using their ranches.

An activist from Orellana, who knows the Amazon, confirmed that there has been an increase in the number of small dirt roads that are being used by armed groups to move around.

In his interview to Código Vidrio, Commander Adatty did not provide details of how armed groups operate in those areas. He only confirmed that there are alliances between the CDF and local gangs, without specifying which gang because, according to him, the agreements and disputes depend on their ringleaders.

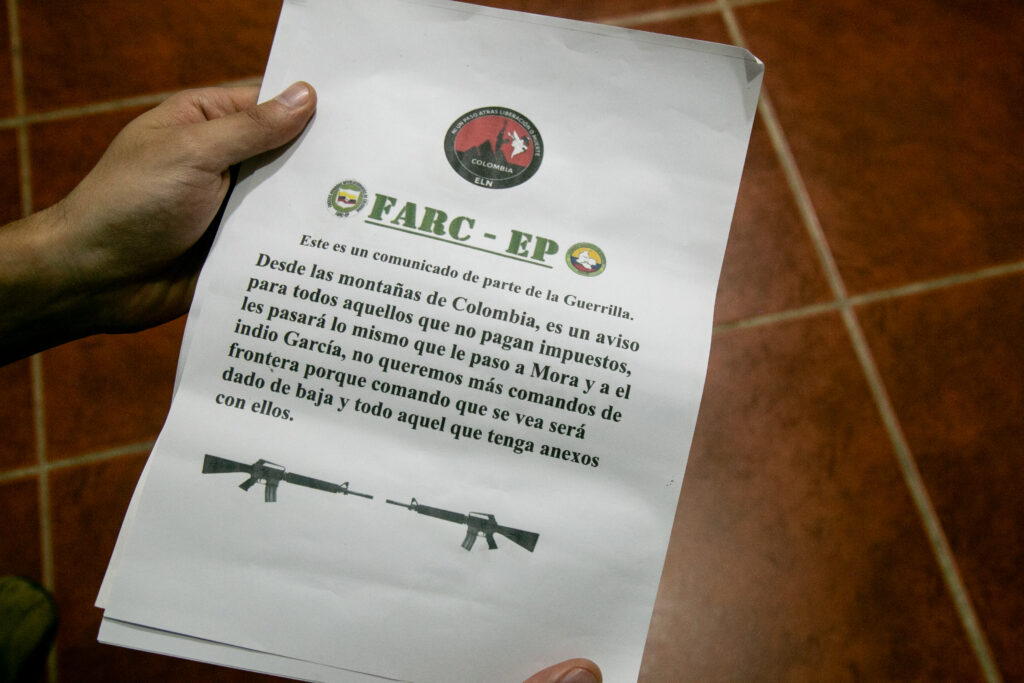

Other events show the violence in Orellana and the clashes between the military and armed groups. Last February, the Armed Forces killed one man and detained two others in the Upper Punino area. The objects seized include seven tricolor patches with the initials FARC-EP. Two days later, two people were captured in Joya de los Sachas with military uniforms and five FARC-EP armbands.

“What are the FARC doing here? Does anyone want us to believe that the FARC are here? I’d feel better knowing it’s the FARC, but we know organized crime is entrenched in this area,” says a social leader who has visited rural areas of Orellana and for whom the attire of the extinct Colombian guerrilla group seems odd.

In Joya de los Sachas, also in February, the military found the bodies of seven men with bullet wounds, dressed in military suits in the trunk of a truck. They said that they were not members of the armed forces. In the same town, another massacre in April was connected to the CDF. An armed group attacked a bar and killed four people. Days later, in an operation against mining in another area – Cascales – the military detained Robinson A., AKA Cejas, who is a member of the CDF according to the Police. The authorities are positive that he led the attack in Joya de los Sachas, according to images recorded outside the bar.

Violence “has increased by 100%,” says Diógenes Zambrano, an environmental activist and human rights advocate. The armed groups “decide who enters and who leaves (…) They are not joking, they will punish any slip-up,” says another activist who visited the Upper Punino mining area late last year and did not want to be identified either.

THE GOLD OF SILENCE

Locals feel that the groups have absolute control and have been co-opting people to extend their network of informants and lookouts, such as those who, in late February, did not lose sight of the narrow path that reaches the heart of the mining area in the Punino.

Since July 2022, there have been reports of transit of heavy machinery. There was even a demonstration in Guayusa because the backhoes were damaging the road. Months later, in November, hooded people with weapons were seen, according to a report sent by social leaders to civil and military authorities, which received no response. In December 2022, 20 commune presidents from San José de Guayusa complained to the authorities about the devastation that illegal mining was causing in the Punino, Sardinas, Lumucha and Acorano rivers, where dead or dying fish appeared as a result of pollution. “The rivers are virtually dead,” an indigenous person told the Pan-Amazon Ecclesial Network.

There are also reports of tolls being imposed in Santa Catalina. In tents made of plastic and sticks, people from the district – whose relationship with the miners or armed groups is unclear – charged US$ 5-200, depending on the types of vehicles and what they were carrying. In addition, there are reports that local residents rented their properties as warehouses to store gold material, chainsaws and mowers. In San Lorenzo, on the other hand, they opened businesses known as electromechanic shops to fix heavy machinery and sell spare parts.

There are also those who approve of mining in the area. After the first signs of discomfort, the miners began to give them fuel and money and “if someone got sick, the miners would lend their car,” said the guide with the hat. They also pay for parties and Christmas celebrations or fix up the church, according to statements collected in the area.

Those who were protesting have preferred to stop doing so. Every week, a group of citizens used to demand, in front of the Prosecution Service’s Office, that the authorities pay attention to the serious contamination of the Punino River. But since the end of 2023, these public demonstrations ceased because social leaders, human rights activists and journalists were threatened.

Silence is a shadow that accompanies Orellana residents. “They have ears everywhere,” says the guide with the hat. That is why it is not easy to take photographs or record videos that attract attention. One interviewee said: “Carrying a camera is like signing your own sentence.”

The panorama becomes more complex because, in addition to the presence of Los Choneros and the CDF in Orellana, there are Los Lobos – another gang included in the list of “terrorist groups” and a rival of Los Choneros. In November 2023, the bodies of two men were found hanging from the Payamino River bridge on the Coca-Loreto road. They were half naked and had signs of torture and bullet holes. One was Colombian and the other was Ecuadorian with a wolf tattoo. This led the Police to presume that that group that has been behind illegal mining, mainly in Ecuador’s Sierra region.

There is little information about the activities of Los Lobos in Orellana. But last February, an image of a pamphlet written in capital letters circulated on WhatsApp, threatening government employees and students with kidnapping if they left their homes. It was supposedly signed by Los Lobos and Los Tiguerones, another criminal gang. The pamphlet announced the start of a war: “We already did it in Sacha, now we’ll do it in El Coca.”

In San José de Guayusa, the abandonment is evident. According to the guide with the hat, there used to be a military checkpoint where the lookouts were guarding the road to San Lorenzo. But on our journey last February, in the midst of a state of exception and combat against the gangs that the Government has classified as terrorists, Amazon Underworld did not see any military or police control in that rural area or in urban districts.

By declaring a state of emergency, President Noboa sought to militarize the most violent areas of the country, especially the largest cities on the Costa region, where drug coming mainly from Colombia is shipped. Those shipments fuel disputes between criminal groups and their war against the State. But no specific public policy has been implemented for the Amazon.

The Punino has been left to its own fate. In the middle of the Amazon jungle, it is a war zone that grows silently with no one to witness it.

* This investigation was produced for Amazon Underworld by a team of journalists from the Ecuadorian outlet Plan V. The text is not signed with the names of the reporters for security reasons.

Amazon Underworld is a joint investigation of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Armando.Info (Venezuela) and La Liga Contra el Silencio (Colombia), Plan V (Ecuador) and the Environmental Information Network (RAI, Bolivia). The work is carried out in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and financed by the Open Society Foundation, the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN NL).