An analysis of two carbon credit projects in the Brazilian Amazon has found that they may be connected to illegal timber laundering. The projects belong to Ricardo Stoppe Jr., known as the biggest individual seller of carbon credits in Brazil, who has made millions of dollars selling these credits to companies like Gol Airlines, Nestlé, Toshiba, Spotify, Boeing and PwC.

Two major carbon offset projects in the Brazilian Amazon, whose credits have been sold to companies like Gol Airlines, Nestlé, Toshiba and PwC, may have been used to launder timber from illegally deforested areas.

The conclusion comes from an analysis by the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA), a Netherlands-based nonprofit founded by prosecutors and investigators that investigates emitters of climate-warming greenhouse gases. Brazilian authorities had already launched timber laundering probes in the areas covered by CCCA’s analysis, which resulted in the suspension of logging authorizations. The owner of a company responsible for one of these projects has a prior conviction for timber laundering.

CCCA made the analysis at Mongabay’s request after an anonymous source highlighted the participation of people convicted of timber laundering in the projects.

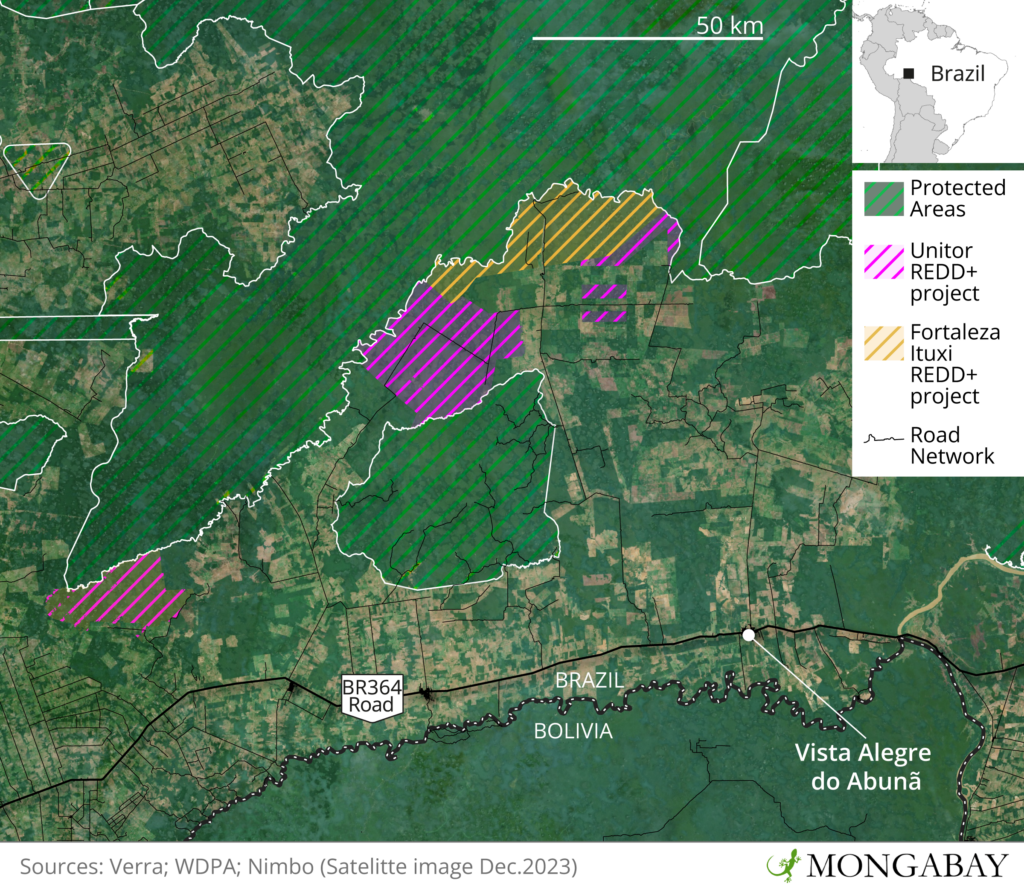

CCCA analyzed two REDD+ projects, called Unitor and Fortaleza Ituxi, in the municipality of Lábrea, in Amazonas state. The two projects cover a combined area of 140,862 hectares (348,078 acres) — twice the size of London — and aim to avoid 660,598 metric tons of CO2 emissions per year by preventing the spread of deforestation in one of the Amazon’s most under-pressure areas.

REDD+ stands for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. The idea behind it is that landowners receive money for protecting an area that could otherwise be deforested. Emissions that are avoided as a result of this protection can then be sold as carbon credits; companies buying them can say to their clients and investors that they’re “offsetting” their carbon footprint and helping to fight climate change by keeping strategic forests standing.

Both of the projects CCCA looked at rely on sustainable forest management plans, a system in which timber is cut and sold under stringent environmental regulations, as one of the main tools to guarantee surveillance of the area and avoid illegal deforestation. “The presence of workers in management activities is the first factor to inhibit the pressures of invasions inside the Project Area,” states a presentation by Fortaleza Ituxi. “Most methodologies allow sustainable logging,” Bárbara Bomfim, a Brazilian forest engineer and carbon expert at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the U.S., told Mongabay.

In these two cases, however, CCCA found inconsistencies between the volume of timber declared to authorities and the logged volume estimated through satellite images — a mismatch that indicates these areas may have been used to launder the equivalent of more than 4,200 truckloads of wood.

Grupo Ituxi, the company behind both projects, denied in a statement to Mongabay any connection with timber laundering and said all of its initiatives are audited, verified and recorded.

In Brazil, all timber must be accompanied by a document called a DOF, the Forest Origin Document, also known as a timber credit. Once a forest management plan is approved by environmental authorities, its owner can issue a certain number of DOFs, corresponding to the volume of trees they’re allowed to extract from that area.

Timber laundering in Brazil is illegal and involves buying fake timber credits from underexploited forest management projects. The credit is issued by approved timber projects, but the trees they correspond to aren’t cut down. Instead, criminals use the fake documents to claim timber taken illegally from areas where logging is banned, like Indigenous lands and conservation areas.

Some criminal groups in Brazil specialize in getting forest management plans approved by environmental agencies only to issue false timber credits, Federal Police deputy Alexandre Saraiva told Mongabay in a video call. “Once we got a phone tap in which the owner of a logging company said, ‘I’m not worried about wood, I have wood here for free, what I need is a DOF,'” he said.

Saraiva worked on some of Brazil’s largest busts of illegal logging groups in the Amazon. “Imagine a criminal organization that sells stolen cars. That car will only be sold for a reasonable price if it has a document. It’s the same with wood.”

Once we got a phone tap in which the owner of a logging company said, ‘I’m not worried about wood, I have wood here for free, what I need is a DOF’.

Alexandre Saraiva, Federal Police deputy

To assess the size of the exploited areas logged in the forest management plans for the two REDD+ projects, CCCA used a satellite-imaging technology called NDFI (normalized difference fraction index) that highlights the scars left in the forest by loggers. The same technology is already used in Brazil by the Federal Police, the environmental agency in the state of Pará, and by Simex, the logging monitoring system developed by independent research institutes like Imazon, Imaflora, Idesam and ICV.

CCCA multiplied the logged area shown in the satellite imagery by the average volume of wood per hectare registered in each forest management plan authorization. This average is calculated from a forest inventory made on the ground by the project’s proponent.

The result showed CCCA an estimate of how much wood was likely logged over a period of time. CCCA then compared this to the volume declared to IBAMA, the federal environmental agency, in the DOF system.

If the volume of timber in the DOF system is substantially higher than that of the timber estimate, it could indicate that the additional credits were used to cover timber logged elsewhere and laundered through these projects.

The analyses of the Fortaleza Ituxi and Unitor forest management areas showed several inconsistencies that strongly point to a possible case of timber laundering, according to CCCA. The most striking case is the forest management plan for Fortaleza Ituxi, which, according to the satellite imagery, had only 35% of its area logged from 2018 to 2019, accounting for an estimate of around 48,588 cubic meters (1.71 million cubic feet) of wood.

In the DOF system, however, the project’s owners reported having extracted 104,700 m³ (3.7 million ft³) from the area in the same period, more than twice the logged volume estimated by CCCA. “This is a fraud,” Saraiva said after reviewing CCCA’s findings.

CCCA said that its method provides approximated volumes, and real numbers can only be determined by a local audit. The complete report and methodology can be seen in a report published on the organization’s website.

Gustavo Geiser, a Federal Police forensic expert in Pará state, said his team uses the same methodology as CCCA when they investigate illegal logging there. “This case you described, for example, has strong indications of timber laundering,” he told Mongabay in a video call.

This case you described, for example, has strong indications of timber laundering.

Gustavo Geiser, Federal Police forensic expert in Pará state

Inconsistencies were also found in logging activities at the Três Barras ranch, part of the Unitor REDD+ project. In one of the ranch’s forest management plans, the proponents declared 25,371 m³ (895,968 ft³) of wood as sales, but the CCCA estimated they extracted at most 71% of that volume.

In another forest management plan for the same ranch, the volume declared was 24,148 m³ (852,779 ft³), but CCCA estimates they logged around 58% of that volume. CCCA also found signs of timber laundering in Presidente Prudente, another farm covered by the Unitor project, where 18,547 m³ (654,981 ft³) was declared from a logged area. According to CCCA analysis, the area shouldn’t have supplied half that amount. “Those are strong indications of a possible credit transaction without real backing in the wood,” Mikael Freitas, a data analyst at CCCA, told Mongabay.

In total, CCCA’s analysis suggests that 84,886 m³ (2.99 million ft³) of timber was covered by potentially fake DOFs issued by the carbon credit schemes, which would be enough to launder the equivalent of more than 4,200 truckloads of wood.

“I’m impressed,” said Gustavo Pinheiro, who has worked for more than a decade in organizations like The Nature Conservancy and the Institute for Climate and Society. “We knew there were technical problems with these projects, especially with Fortaleza Ituxi. But this is something much worse. It looks like a police case.”

While in some areas the projects extracted much less timber than they declared, in others they did the opposite. In the São Sebastião ranch, part of the Unitor project, satellite imagery suggests extraction of 11,859 m³ (418,796 ft³) of wood, but no timber was declared in the DOF system. This also happened in another forest management plan in the Fortaleza Ituxi project, where an area of more than 1,700 hectares (4,200 acres) was explored without proper paperwork.

“This dynamic of having one management plan executed in one way and another in another way indicates a process that is highly adapted to the irregularities of the timber market in the Amazon,” CCCA’s Freitas said. All evidence points to a business model that isn’t concerned with environmental conservation, he added. “On the contrary, we see an effort to over-optimize financial gain from the forest, both through the apparent overexploitation of timber in some areas and through the use of other areas to generate DOF, as well as the selling of carbon credits.”

We see an effort to over-optimize financial gain from the forest, both through the apparent overexploitation of timber in some areas and through the use of other areas to generate DOF, as well as the selling of carbon credits.

Mikael Freitas, data analyst at CCCA

Both Unitor and Fortaleza Ituxi are led by Ricardo Stoppe Jr., a doctor from São Paulo, and certified by Verra, one of the world’s largest voluntary carbon market registries and the most important for REDD+ initiatives.

Stoppe’s company, Grupo Ituxi, said it only owns the forest management plans and that logging is carried out by third parties. “We only mediate commercial relations with interested parties able to carry it out — companies that have their own staff and machinery to harvest the wood,” it said. Grupo Ituxi also contested the findings of CCCA’s analysis, saying satellite imagery isn’t enough to assess actual logging volumes, which it added could only be achieved by an on-site inspection.

A Verra spokesperson said the company needs more details about the analyses before commenting on the findings.

According to Brazilian business news outlet Exame, Stoppe is the largest individual seller of carbon credits in Brazil and has been celebrated as “one of the best examples of how to make money while keeping forests standing.” “I live here and this place has become my life. I’m in love with the Amazon,” he said in an interview.

His projects were developed by Carbonext, a Brazilian company known as the largest carbon credit generator in the country and specialized in structuring the projects, calculating their deforestation baselines, and conducting all the bureaucracy around the registries and audits.

In a statement to Mongaby, Carbonext said it wasn’t involved with the forest management carried out in the area, and that “there are no scientifically recognized ways of determining the volume of wood in forest management projects based solely on satellite images.”

Previous investigations pointed to timber laundering

Before the CCCA analysis, Brazilian authorities had already found signs of timber laundering in Unitor and Fortaleza Ituxi.

In October 2021, agents from IBAMA, the federal environmental agency, went to Divisa, a sawmill in Vista Alegre do Abunã district, at the border of BR-364 highway. According to IBAMA’s inspection report, their goal was to verify a suspicious timber transaction of 13 DOFs, corresponding to 233.76 m³ (8,255 ft³) of wood, that the company declared to have received from a forest management plan in the Nossa Senhora das Cachoeiras do Ituxi farm, where the Fortaleza Ituxi REDD+ project is located.

When the inspectors asked to see the timber, however, the sawmill’s manager said: “There had been no movement of wood, but only a virtual movement to adjust Divisa’s yard.” The agents concluded that the DOFs were aimed at “covering up the same volume of wood received illegally by the company.”

According to IBAMA, the case was even more serious due to the sawmill’s proximity to Indigenous territories and protected areas under pressure from illegal loggers. The agents also indicated this could be the tip of the iceberg, since 11 other companies had received 55 DOFs from the same forest management plan during a period when the property was inaccessible.

At that time, the Fortaleza Ituxi carbon project was already generating credits certified by Verra. IBAMA fined Stoppe’s venture, named Stoppe LTDA, 211,500 reais ($39,200 at the time) and blocked the company’s access to the DOF system. It characterized the scheme as “a licensed [forest] management that used the preapproved credits to cover up illegally logged timber.” According to IBAMA, the ban was lifted less than a year later, in August 2022, due to an injunction.

In its statement, Grupo Ituxi said “there was a problem with the registration of one of the documents” due to poor internet connection, but that the timber was delivered to Divisa.

Authorities had also found indications of timber laundering in some farms within the Unitor REDD+ project, described by its proponents as “a consortium of neighboring properties … who have come together to develop forest carbon activities.” The area comprises 12 ranches covering a combined 94,270 hectares (nearly 233,ooo acres).

In May 2023, two of these farms — Três Barras and São Sebastião — were targeted by IBAMA in an anti-fraud operation. According to the agency’s press office, four forest management authorizations for the two properties were suspended. The investigators, who like CCCA analyzed satellite imagery and DOF issuances, concluded the aim of the fraud in the DOF system was “to cover up illegally logged timber in other places, such as indigenous lands, conservation units and unauthorized areas.”

Stoppe told Mongabay that the Três Barras and São Sebastião farms aren’t managed by the Ituxi Group and that IBAMA’s suspension of Três Barras’s forest management authorization was made without any on-site inspection.

Três Barras is the largest property in the Unitor project and is located 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) from the BR-364 highway. Mongabay visited the farm in August 2023 and found areas of cattle ranching and forest management. None of the neighbors or the property employees we spoke to said they were aware it was part of a carbon offset project.

During a probe against illegal logging led by the Federal Police and the federal prosecutor’s office in 2017, known as Operation Arquimedes, authorities identified the area as one of the sites allegedly used to generate false DOFs to cover up for illegal timber taken from elsewhere.

The information is part of a court decision on Élcio Aparecido Moço, whose company, Green Forest Carbon, is one of the proponents of the Unitor project, alongside Stoppe and Carbonext. Moço’s companies and family members also own most of the land in the Unitor area. Another of his companies, Rio Negro, is also mentioned in Verra’s reports as being responsible for supervising Fortaleza Ituxi’s forest management plans.

Before being investigated in the Arquimedes probe, Moço had already been sentenced for timber laundering in 2017 — two years later, a superior court decided the case had already prescribed and he could no longer be punished. Also in 2019, he would be indicted for allegedly bribing two public officials to obtain a license for a forest management project. A judge has taken on the case but no trial date has been set yet.

“I remember Moço,” said Saraiva, who worked on the Arquimedes investigation. “He was an old-time wood entrepreneur who had a good part of IPAAM in his hands,” he added, referring to the environmental agency in the state of Amazonas.

Mongabay made several attempts to contact Moço by email and phone to put the allegations to him, but were unsuccessful. Grupo Ituxi said Operation Arquimedes preceded the creation of the Unitor project.

Moço co-owns a business conglomerate with Stoppe’s son, Ricardo Villares Lot Stoppe, consisting of seven companies. It includes Rio Grande Produção Florestal, which was fined a total of 2.8 million reais ($519,000 at the time) for deforesting 572 hectares (1,413 acres) in 2021. The conglomerate has also partnered with individuals like Cleyliane Lopes de Moura, arrested in 2006 for selling illegal timber, and José Luiz Capelasso, who was sentenced for illegally trading DOFs in 2012. According to the investigation, Capelasso charged 3,000 reais (about $1,500 at the time) for each fake document. In one of Unitor’s verification reports, Capelasso is also presented as being responsible for activities like “operational management structure” and “crediting period.”

In a WhatsApp message to Mongabay, Capelasso said he wasn’t the “official owner” of the projects and recommended Mongabay get in touch with Grupo Ituxi. Regarding the Rio Grande fine, Grupo Ituxi said the area was deforested before the company bought it. Mongabay couldn’t reach Moura for comment.

Millionaire profits

According to documents attached to a public lawsuit, Stoppe and his partners had earned more than 80 million reais ($15.5 million at the time) from carbon credits by 2020. Stoppe has also signed a call option contract up to $2.5 million with an investment fund in the United States, in an operation intermediated by Moss, a Brazilian company that describes itself as an environmental fintech (a financial technology company) that operates as a carbon credit broker.

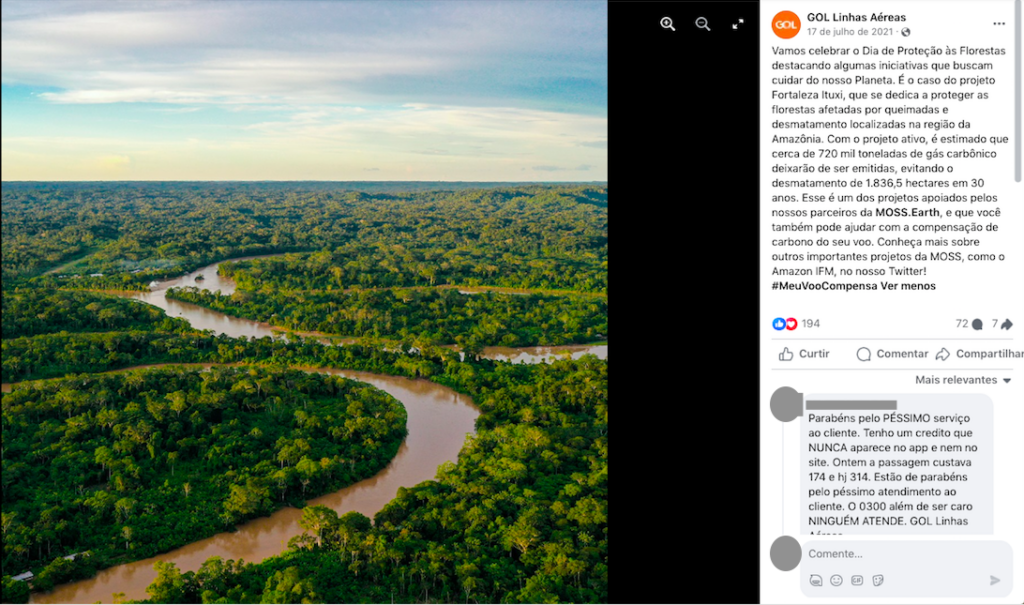

Fortaleza Ituxi sold more than 1.2 million carbon credits to companies from 2022 to 2023, according to Verra. The prime client is Moss, who sold part of these credits to Brazilian low-cost carrier GOL Airlines.

Moss said all credits were bought and sold before the alleged wrongdoing uncovered during this investigation. (Read the full statement here.) GOL told Mongabay that all carbon credits acquired by the company from Moss are audited. (Read the full statement here.)

Other Brazilian companies, such as the food delivery app ifood; Itaú, one of the country’s biggest banks; and Hering, a fashion company, are among the major clients of Forteleza Ituxi. The credits were also used to offset emissions by the Japanese electronics giant Toshiba.

In their respective statements, iFood and Itaú said they had conducted internal due diligence processes before buying the credits. Itaú added: “Any proven case of fraud or environmental crime involving partners will result in the termination of the partnership.” (Read iFood and Itaú’s full statements respectively here and here.) Hering said the credits were purchased through a leading intermediary company, which presented documentation of the validation and integrity of the assets (read the full statement here). Toshiba didn’t respond to emailed requests for comment.

An even larger number of credits, 2.3 million, have been retired from the Unitor REDD+ project. Its top three clients are Colombian state oil company Ecopetrol, Canadian mining company Sigma Lithium Resources, and British auditing firm PwC International. The list also includes other transnational firms like Nestlé.

In a statement, Ecopetrol said it bought the credits from one of the world’s most recognized project developers. (Read the full statement here.) Nestlé Brasil said it acquired carbon credits through WayCarbon, a leading company in the area. (Read the full statement here.) Sigma and PwC didn’t respond to our emails.

Alleged wrongdoing also surrounds another project Stoppe owns in the municipality of Apuí, also in the state of Amazonas, which has sold carbon credits to companies like Boeing and Spotify. A judge in São Paulo blocked Evergreen’s REDD+ carbon credits sale in October 2022 after Carbonext raised doubts about the land registry of one of the project’s properties.

Grupo Ituxi denied any land irregularity in Evergreen. Carbonext said it has achieved the objectives of the case, which has now been closed. (Read the full statement here.) Boeing said it was unaware of the allegations and is monitoring the situation to inform its next steps. (Read the full statement here.) Spotify didn’t respond to our questions.

In total, Stoppe owns five REDD+ projects in the Brazilian Amazon, covering more than 400,000 hectares (nearly 1 million acres), an area more than three times the size of Los Angeles. Two of these projects are still “under validation” or “under development” in Verra.

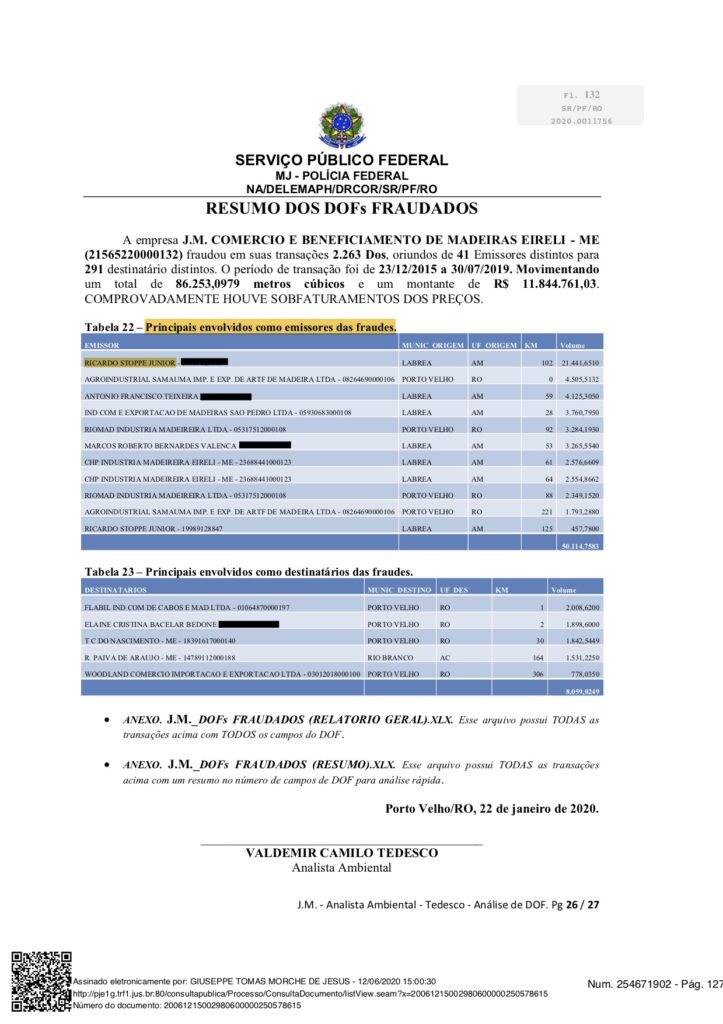

Between 2020 and 2022, Stoppe was mentioned in investigations led by the Federal Police and the federal prosecutor’s office against Chaules Pozzebon, known as one of the Amazon’s largest deforesters, who laundered timber for an illegal logging scheme on the border of Amazonas and Rondônia states, in the same region as the Fortaleza Ituxi and Unitor projects.

According to the investigations, Stoppe was suspected of supplying the paperwork needed to “legalize” the timber illegally extracted from the forest and was allegedly one of the main sources of DOFs to one of Pozzebon’s sawmills, called J.M.

From December 2015 to August 2019, he reportedly issued the equivalent of 57,472 m³ (2.03 million ft³) of timber valued at 4.8 million reais ($1.2 million at the time) to J.M. But the large distances between his forest management projects and its supposed clients garnered the attention of investigators.

“The distance between management and the sawmill ends up making transportation costly from a commercial point of view. This fact indicates that the management may be used only to allocate credits to J.M,” investigators wrote in a report.

The federal prosecutor’s office in Rondônia told Mongabay that Stoppe wasn’t indicted by the Federal Police or charged by the prosecutor’s office in that case because there wasn’t enough evidence against him at the time. “If new, more robust evidence against him emerges, nothing prevents the reopening of investigations and even the opening of a lawsuit,” it said in an email.

Grupo Ituxi told Mongabay that, “in the past, Chaules Pozzebon was one of the clients who extracted forest management from Fortaleza Ituxi.” It added there was no evidence of any connection between Stoppe and the conduct of those being investigated by the authorities. (Read the full statement here.)

Public records analyzed by CCCA show that the timber credits that indicate laundering from the REDD+ areas were sent to dozens of sawmills, among them four companies belonging to Pozzebon, according to the Federal Police.

According to IBAMA files, Stoppe and Moço also issued DOFs to several sawmills with a history of fines for storing and transporting illegally logged timber and for including fake information in the DOF system, including Cesar Ronhiski, with 21 fines, Adelson & Zapeline, with 17 fines, and Madeireira Bom Jesus, with 11.

Pozzebon is currently in jail, having been sentenced to 100 years in prison in 2021 for extortion and being part of a criminal organization. In May 2023, his sentence was reduced to 70 years.

Auditors’ approval

REDD+ projects are currently not subjected to any official regulation in Brazil, where Congress is still discussing the approval of a regulated carbon credit market. In a bid for credibility, many carbon offset projects must abide by methodologies like the ones created by U.S.-based certifier Verra.

The system has been under intense scrutiny from news outlets and the scientific community, either for overstating its environmental results — and, therefore, its profits — or because of unfair and deceitful dealings with local communities hosting the projects. In January, The Guardian found that more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets certified by Verra may be worthless. In August this year, a study published in the journal Science showed that millions of carbon credits may have been generated by overstating projects’ forest protection benefits.

To issue carbon credits, a project must be verified by an independent auditor. This independence, however, is relative, since the project developer pays the auditors’ fees. “Auditing has to improve a lot and it has to come from a real third party, not someone chosen by the project developer,” Bárbara Bomfim, who was previously affiliated with the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project at the University of California, told Mongabay. “These people who run a lot of REDD+ projects are already creating relationships with these auditors. They say, ‘I’m going to hire you and I’ve already got 10 other projects in the pipeline, so let’s do everything?’ So they end up becoming business partners.”

Verra said there are various safeguards and ethical standards in place to ensure the auditors’ independence and impartiality, despite being paid by the entity being audited. (Read the full statement here.)

Neither audit reports for Unitor nor Fortaleza Ituxi — prepared by Earthood (an Indian company), Icontec (Colombia), Rina (Italy) and Aenor (Spain) — mentioned any issues with the forest management plans located inside these REDD+ projects. The exception is one inconsistency in the volume of timber extracted from Unitor’s area and declared by the project proponent in the April 2022 verification report.

The auditors from Rina pointed out a mismatch between the numbers declared in one table and the ones from a spreadsheet they’d received, which isn’t public. The case was closed less than 20 days later, after the project proponent updated the information on the table.

Aenor said in an email that all the information shared by Mongabay predated its verification process in Unitor, which ranged from August 2021 to July 2022. (Read the full statement here.) Rina said the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) doesn’t require the assessment of criminal records or independent analysis, but only the compliance of a project with the standard. (Read the full statement here.) Earthood and Icontec didn’t respond to our emails.

“The verifiers aren’t even Brazilian, they don’t know the Brazilian reality. So these audits end up being very formal: ‘Do you have the document here? Yes, then check’,” said Pinheiro, formerly from the Institute for Climate and Society, who recently joined the impact investment company Trie Capital. “The fact is that the methodology is not doing what it sets out to do, which is to guarantee the integrity of projects.”

This report is part of the Opaque Carbon project, an alliance that investigates the functioning of the carbon market in Latin America and includes Agência Pública, InfoAmazonia, Mongabay Brasil y Sumaúma (Brazil), Rutas del Conflicto and Mutante (Colombia), La Barra Espaciadora (Ecuador), Prensa Comunitaria (Guatemala), Contracorriente (Honduras), El Surtidor (Paraguay), La Mula (Perú) and Mongabay Latam, led by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP). Logo design: La Fábrica Memética.