Chief Afonso Maricaua, from the Kokama people, of the Estrela da Paz Indigenous Land, in the Upper Solimões. Photo: Christian Braga/InfoAmazonia

The promise of an exclusive university for the Indigenous peoples of the Upper Solimões region, in Brazil’s Amazonas state, persuaded leaders from at least six territories to sign pre-contracts with Colombian companies to generate carbon credits. However, the company has not complied with guidelines of the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) and recommendations of the Federal Prosecution Service (MPF).

The project presented by José Antonio Pérez Manrique from Colombia, who crossed the border into Brazilian Indigenous lands, involves funding a higher education unit with money from sales of carbon credits. The university’s project led the communities to sign a pre-contract with Colombian company Concepto Carbono to develop the initiative, which three other allied Colombian companies — Carbo Sostenible, Terra Commodities and Yauto — later started planning. However, the creation of the university and the development of carbon credit projects in the area have not been authorized by Brazilian authorities so far. This process, in which the four companies and Pérez Manrique himself were involved, led Indigenous leaders to sign documents with potentially abusive clauses and to move forward with projects that do not comply with the duty of prior consultation provided for in international conventions on Indigenous rights.

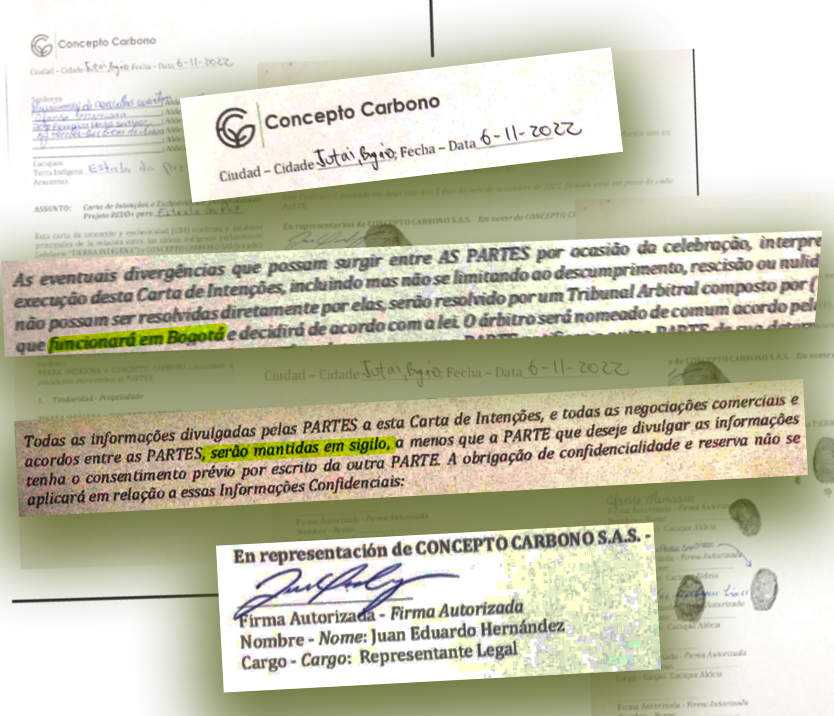

In August 2022, FUNAI denied authorization for representatives of Colombian companies Carbo Sostenible, Terra Commodities and Yauto to enter the Upper Solimões territories. The agency also advised Indigenous communities against signing agreements since the carbon market was not regulated in Brazil. Three months later, on Nov. 6, 2022, at least six “exclusivity letters” were signed with Concepto Carbono, authorizing the company to implement a carbon sequestration project in the forest areas of the Riozinho, Biá River, Estrela da Paz, Macarrão, Espírito Santo and Acapuri de Cima Indigenous lands. The agreement — some sort of pre-contract where the parties already have their duties — included areas that had not even been officially approved as Indigenous lands by the federal government.

FUNAI said it was not aware of such “exclusivity letters” signed by Indigenous leaders but states that “all contracts risk being annulled, given technical and legal questions regarding feasibility, required procedures and compliance with socio-environmental safeguards, including the right to free, prior and informed consultation [FPIC].”

FPIC is one of the mandatory conditions provided for in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) and addresses traditional communities’ right to be consulted about projects that impact their territories and ways of life. In July this year, the Federal Prosecution Service (MPF) issued a Technical Note to guide federal prosecutors on carbon projects in Indigenous lands. The document stresses the need for technical monitoring by the government and warns that “prior consultation must take place during the planning stage and before any decisions are made.”

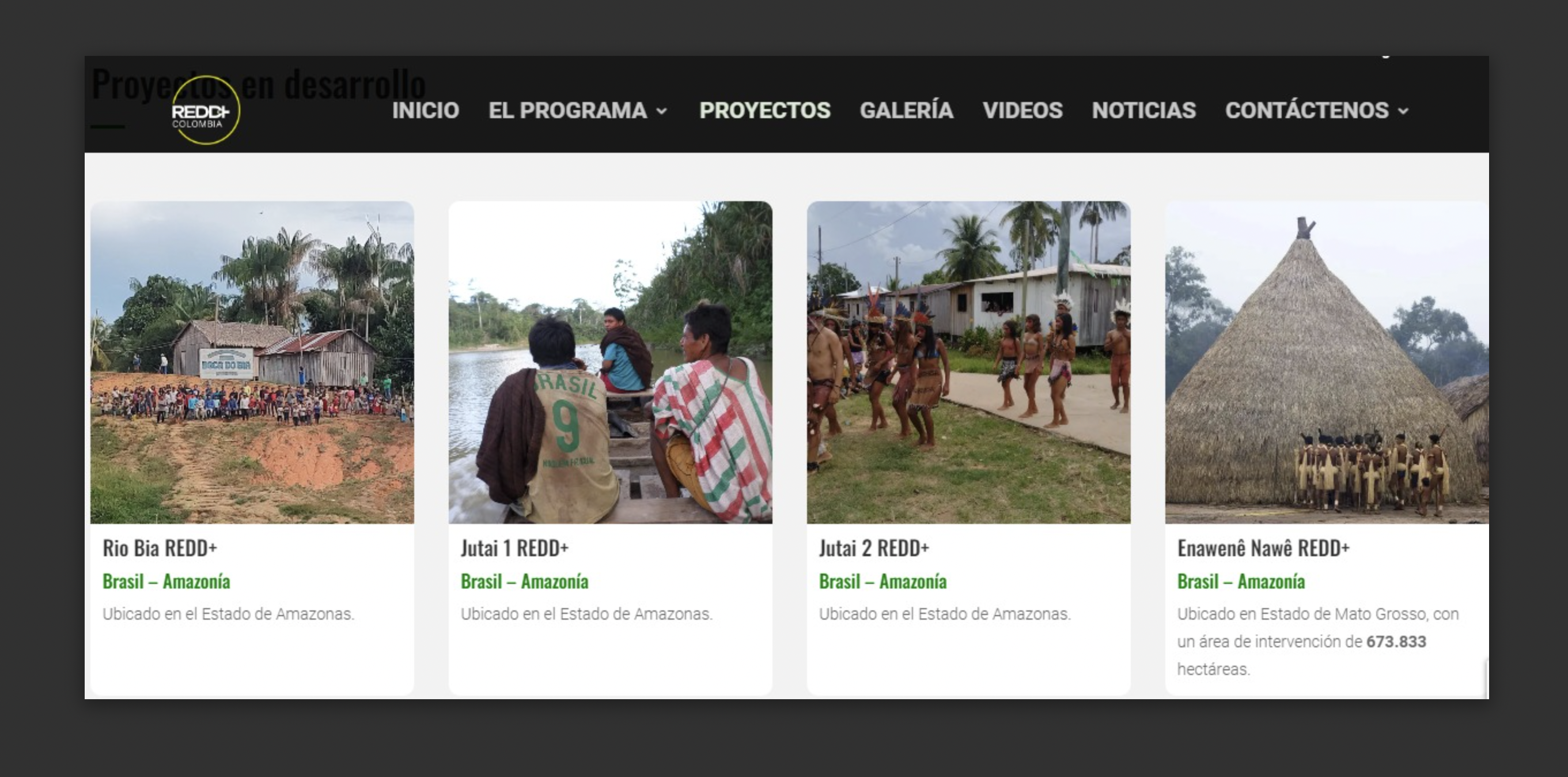

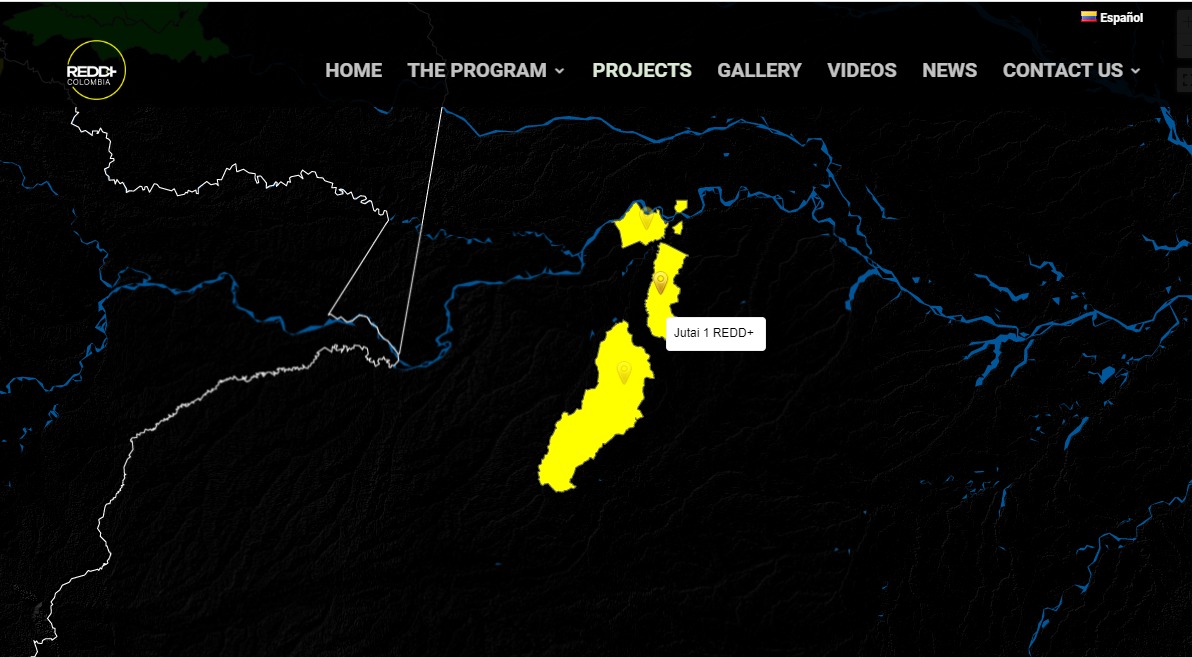

The projects signed with Concepto Carbono cover 1.6 million hectares (4 million acres) in Indigenous lands in the municipalities of Jutaí, Fonte Boa, Carauari and Juruá, all in Amazonas state and close to Brazil’s triple border with Colombia and Peru, in territories occupied by the Kokama, Katukina, Miranha, Kambeba, Tikuna, Kanamari and Kulina Indigenous peoples. The six agreements signed by village chiefs gave rise to three carbon credit projects called Jutaí-1, Jutaí-2 and Rio Biá, which are listed as being in their development stages in the portfolio of CommunityRedd+, an alliance of Colombian companies that implement environmental compensation projects in traditional communities in Colombia and, more recently, Peru and Brazil.

In addition to these six pre-contracts in the Solimões area, the group also has a carbon project in the Enawenê-Nawê Indigenous land in Mato Grosso state, where there are even some isolated peoples. The project includes a Brazilian company called JGP Consultoria e Participações Ltda. According to the CommunityRedd+ website, the project is also in its development stage.

In the August 2022 official letter sent to its Regional Office in the Upper Solimões, FUNAI’s Brasília office justified that “carbon credit trading in Indigenous Lands has peculiarities that raise doubts and require specific criteria, as these lands are owned by the Federal Government for permanent possession and enjoyment of Indigenous people.”

According to FUNAI’s attorney’s office, any carbon project on Indigenous lands requires authorization from the federal government, which did not happen in the agreements signed in the Upper Solimões or Mato Grosso.

Over the last 10 months, InfoAmazonia investigated carbon projects that gave rise to the series “Money that grows on trees: Financialization of the forest puts pressure on Indigenous lands.” The series explores carbon project contracts in traditional territories in the Brazilian Amazon with suspected illegalities.

Bugaio village in the Estrela da Paz Indigenous Land, Jutaí (AM). Photos: Christian Braga/InfoAmazonia

In September this year, we visited the communities of the Upper Solimões and found out that the Colombians’ carbon credit project arrived in the region with the promise of implementing the so-called Distinguished Indigenous University of Amazon Peoples (UIDPA) – an idea that persuaded the communities and became the main reason for Indigenous leaders to accept the agreement with Concepto Carbono.

None of the projects included prior consultation along the lines of ILO Convention 169, and decisions have been restricted to chiefs and leaders with whom the businesspeople keep in contact. So far, the projects are virtually unknown to the vast majority of community members.

In the agreements signed, Indigenous leaders commit to complete confidentiality regarding “the letter of intent,” otherwise they would not be complying with the agreement: “All commercial negotiations and agreements between the parties will be kept confidential,” said the document signed by the Indigenous leaders with Juan Eduardo Hernández from Concepto Carbono.

The Indigenous people cannot initiate, advance or sign any other “emissions reduction” projects without authorization from Concepto Carbono, since each territory can only sell results from avoided deforestation once and, therefore, there cannot be other projects.

Furthermore, the agreement defines that both parties choose an arbitration court in Colombia’s capital, Bogotá, as the venue for resolving any disputes.

According to experts, that clause could be considered abusive because of “economic inequality between the parties and difficulty in accessing the legal system,” as explained by lawyer Brenda Brito, an associate researcher at Imazon who holds a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in legal science from Stanford University (USA). “I think this contract would be easily declared null and void if it were taken to Brazilian courts,” Brito said.

The documents state that the Indigenous people would keep up to 70% of revenues from carbon credit sales. But the costs they would have to bear to keep the project’s forest area intact — without deforestation — or how they would use that money are not clear.

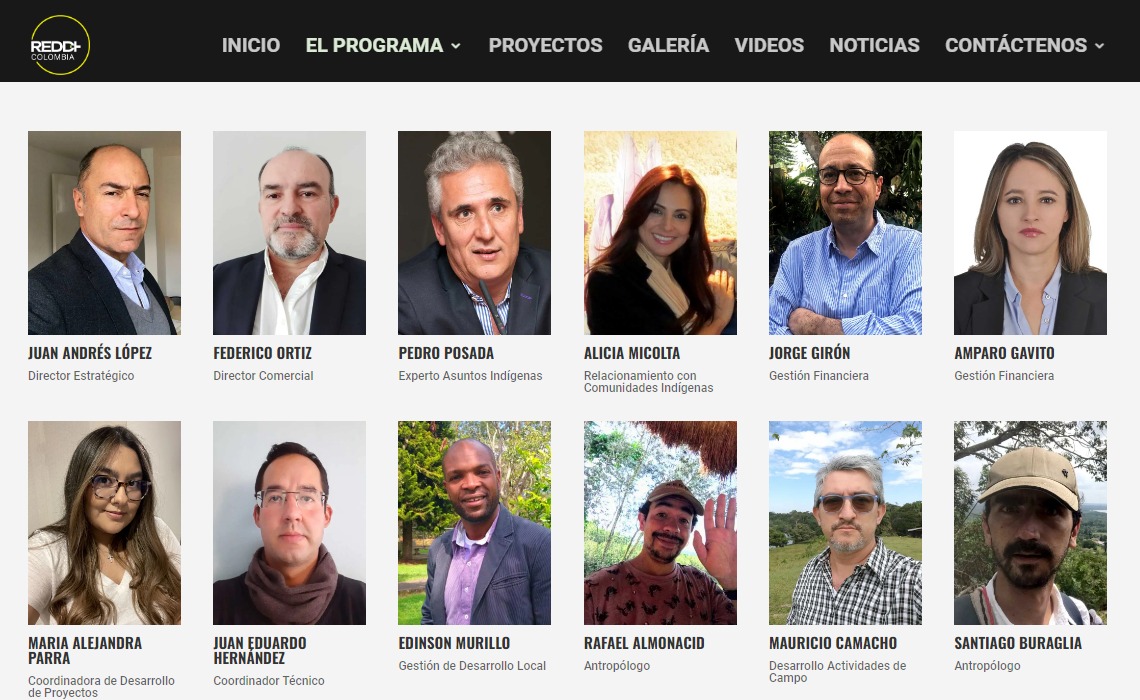

Although the pre-contracts were signed only with Concepto Carbono, other documents obtained by InfoAmazonia, such as the business model and work proposal for the development of the program, show that the project presented to the Indigenous people includes three other companies that operate in the Colombian carbon market: Carbo Sostenible, Terra Commodities and Yauto, which, together with Visso Consultores and Plan Ambiente, make up the CommunityRedd+ alliance. The group’s member companies say they have global clients in other projects, such as Coca-Cola and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The leaflet given to Indigenous leaders includes the logos of the four companies.

In March, the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) revealed that the same companies involved in carbon projects in the Solimões area — Carbo Sostenible, Terra Commodities and Yauto — and linked to CommunityRedd+ excluded local Indigenous people from the results of a carbon project developed in the Monochoa Indigenous Reserve, in the Colombian Amazon. According to the report, two of the six communities in the territory were excluded from the carbon project, although the land where they live was located within the area negotiated by the companies. Therefore, the two Indigenous villages did not benefit from the carbon credits they were selling in the voluntary market and were unable to participate in other environmental compensation projects.

As they are in their development stage, the projects in the Solimões Indigenous lands and in Mato Grosso are not generating certified carbon credits for sale on the market yet. After being structured with local communities, an independent auditor must assess the quality of the project and then the certifier can approve it. This quality seal is what enables sales of credits in the market, which are usually purchased by companies seeking to compensate for their intensive use of fossil fuels. Each credit is equivalent to one metric ton of carbon dioxide — one of the greenhouse gases that causes climate change — which would no longer be released into the atmosphere as a result of the conservation effort.

In Brazil, Indigenous lands are among the land categories that best preserve Amazon ecosystems. In the last 30 years, 1% of those territories were deforested, while forest loss in private areas was 20.6%, according to the MapBiomas network. This is why they are attractive for those pursuing private carbon projects there.

The CommunityRedd+ website points to Verra as the organization responsible for certifying the carbon credits to be generated by the project at the Enawenê-Nawê Indigenous land in Mato Grosso. But at Verra, the world’s largest carbon credit certifier, there is no record of the project developed at Enawenê-Nawê. The CommunityRedd+ website does not say who will certify the three Solimões projects

Concepto Carbono was created in 2021 and is led by Colombian biologist Juan Eduardo Hernández Orozco, who also appears as technical coordinator of CommunityRedd+, an alliance that includes the companies listed in the document presenting the projects in Solimões and Mato Grosso. One of the most visible figures in that alliance is lawyer Pedro Santiago Posada, leader and shareholder of Yauto, who held the two highest Indigenous rights protection positions in the Colombian state: He served as director of Indigenous affairs at the Ministry of the Interior for eight years, 2008-16, during the administrations of former Presidents Álvaro Uribe and Juan Manuel Santos; and defender for Indigenous and ethnic minorities at the Public Defender’s Office of Colombia (2016-18).

InfoAmazonia sought out the four Colombian companies involved in carbon credit projects in Alto Solimões.

By text message, Hernández said he would not answer because “the focus of the questions ignores the context of a Redd+ project.” He also challenged FUNAI’s information found in the story and said that “the FUNAI office they consulted had no jurisdiction over the project’s area.”

Federico Ortiz, shareholder and director of Terra Commodities and also commercial director of the CommunityRedd+ alliance, stated, also in a message, that “the project belongs to the indigenous people and they are the ones that request and receive authorizations directly from the authorities.” He also said that the projects are not under development yet. “Therefore, everyone who will participate in the development, such as the university, must wait until a path for the project is defined,” he said, without answering other questions in the report.

Yauto and Carbo Sostenible did not answer our questions, nor did they respond to our requests for interviews.

Documents do not mention university

Despite being the main argument presented in the communities for implementing the carbon project, the contracts signed by the Indigenous leaders of Solimões with Concepto Carbono do not mention UIDPA.

InfoAmazonia learned from local sources that Concepto funded the university project in the early months of last year, including the payment of Indigenous teachers from the community itself, when the Indigenous people took classes at the so-called college.

However, after signing the contract with Concepto, the Indigenous people claim that money transfers were suspended and classes were interrupted with the promise of resumption after the carbon project is implemented.

The communities recorded the date: Jan. 5, 2024. The promise is that classes will resume at UIDPA on that day.

And, despite the uncertainties, leaders have expectations about the project.

At Boa Vista village in the Estrela da Paz Indigenous land, a friendly Chief Afonso Maricaua announced the arrival of our team on a megaphone installed in the community’s central area. Chief Maricaua said he signed the pre-contract for the carbon project because he believes the university is an “opportunity for young people in the community” and “to help preserve the forest.”

In their daily lives with their crops or in the lakes where men manage pirarucu, the Indigenous people dream that everything there can change, mainly because they do not feel safe and independent in their territories, in a region of the Amazon, on the triple border, where mercury from mining pollutes rivers, loggers advance into the territories and organized crime is spreading.

According to estimates made by the Indigenous people themselves, more than a hundred mining barges have been operating in the Upper Jutaí area since the 1990s, using mercury and posing threats to local Indigenous communities.

“We always hope that things will get better. Our expectation is that all of this will bring more opportunities to our villages,” said Francieti Estevão Santiago, a resident of the Acapuri de Cima Indigenous land. The area had not been officially approved in November 2022, when it was included in the carbon project.

On the other hand, reports from the Indigenous people we spoke to show that they know little about the carbon project that is being negotiated and much less about the guidelines provided by FUNAI and other agencies.

To date, neither FUNAI nor the Ministry of Education has received any request to regularize the Indigenous university for the people of Jutaí. And there are no expectations that the project can actually be implemented before January 2024, in time for the promised classes to start.

FUNAI did not know about the existence of pre-contracts

In the same month of September, when we were in the Indigenous lands in Jutaí, CommunityRedd+ coordinator and Concepto Carbono director Juan Eduardo Hernández also visited the municipality’s territories, according to the Indigenous people, to “define the project areas,” once again without being monitored or authorized by Brazil’s Indigenous peoples’ agency.

Despite being provoked in August 2022 by the Colombian businesspeople themselves, FUNAI has not made any comment on the carbon projects in the Solimões area since September last year, when it asked its regional coordination to advise communities against signing contracts before the carbon market in Indigenous lands is regulated.

Em 23 de agosto de 2022, as empresas Yauto, Terra Commodities e Carbo Sostenible (Carbo-Terra-Yauto) enviaram ofício ao órgão intitulado “Modelo de Negócios para o Desenvolvimento de Projetos REDD+ com Comunidades Indígenas do Brasil no Estado do Amazonas”.

On Aug. 23, 2022, Yauto, Terra Commodities and Carbo Sostenible (Carbo-Terra-Yauto) sent a letter to FUNAI titled “Business Model for REDD+ Projects with Brazilian Indigenous Communities in the State of Amazonas.”

The document mentions at least five potential carbon projects on Indigenous lands in the Solimões area and asks for “FUNAI’s support and participation” but does not specify the Indigenous lands involved.

“We want to present our way of approaching Redd+ projects directly to community authorities, with FUNAI’s support and participation, to allow for closer ties between indigenous peoples and our companies,” said the letter signed by Juan Andrés López from Carbo Sostenible, Alicia Micolta from Yauto and Federico Ortiz from Terra Commodities.

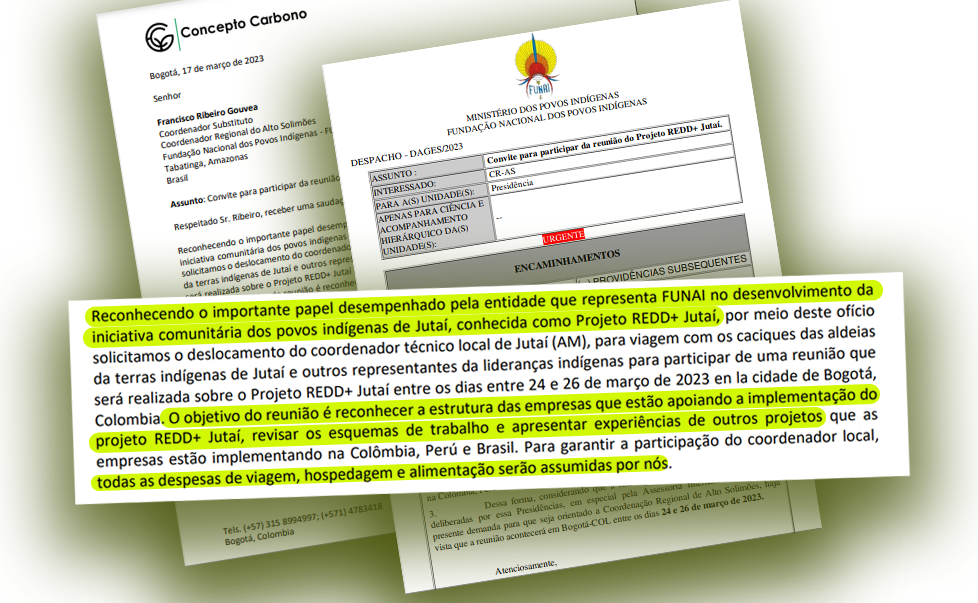

In March 2023, this time in a letter signed only by Concepto Carbono, the company requested authorization to take a FUNAI representative to Bogotá to “know the structure of the companies that are supporting the implementation of the Redd+ Jutaí project and review the work schemes.” The request was sent to FUNAI’s presidency, but there is no record of the agency’s response. However, on March 24, a FUNAI representative did travel to Bogotá at the request of the Indigenous people. Travel expenses were all paid by the companies.

When contacted by the reporters, FUNAI said there was a “request to enter Indigenous land to present a carbon project, but it did not identify which Indigenous lands were the focus of interest.

FUNAI confirmed that its recommendation has always been “that no contracts for trading carbon credits on Indigenous lands be signed until the matter is regulated.” The agency also said that it had no knowledge of the current status of the projects in the Upper Solimões Indigenous lands and did not know about the signing of pre-contracts.

“FUNAI … is not aware of carbon contracts signed in the Riozinho, Rio Biá, Estrela da Paz, Macarrão, Espírito Santo and Acapuri de Cima Indigenous lands. A procedure underway at FUNAI addresses requests by NGO Carbo-Terra to enter an Indigenous land to present carbon credit projects, without, however, specifying which Indigenous lands are of interest,” the agency stated. While we were informed that the request came from an NGO, the three Colombian companies are private enterprises rather than NGOs as FUNAI called them.

University dream

“The Indigenous university will benefit several communities. Today, our students finish high school, but they can’t continue their studies. That’s why we believe that the carbon project will help us a lot in making this dream come true.” Professor Francisco Romão’s words echoed through the cabin where we met with Indigenous leaders in Bugaio village, in the Estrela da Paz Indigenous land, in early September.

One of the main supporters of the university project, Romão dreams of the possibility of working with books in the Kokama language in the classroom and said he believed this was a turning point for the Indigenous people of the Solimões.

The cabin was packed with people. The Indigenous people served pajuaru, a typical Tikuna alcoholic beverage made by fermenting a specific type of cassava. They talked about plans and dreams they have with the arrival of the carbon project.

Village Chief Vanildo Romão da Silva continued speaking of concerns about education and said the community already has a plan to use the funds from the carbon project.

Our project includes quality schools for our community, a health center, transportation, sustainability, solar energy and forest protection. We need higher education for our youth.

Village Chief Vanildo Romão da Silva

“Our project includes quality schools for our community, a health center, transportation, sustainability, solar energy and forest protection. We need higher education for our youth,” said the chief, who complained about lack of support from FUNAI. “We take our demands to FUNAI, and they rarely respond. We are forgotten here.”

João Braz, from the Council of Indigenous Peoples of Jutaí (COPIJU), said he was following the development of the carbon project with caution and some hope. “We believe it because our people need better quality of life. We want to believe it will work.”

When we asked if he knew about FUNAI’s guidelines, he said he knew that the agencies were informed about the project but never advised the community against it.

Opponents of projects fear reprisals

Not everyone agrees on how things have been conducted in the region. During our visit to the villages, we heard criticism and even resistance to the carbon project, and how the idea of the Indigenous university was used to hasten procedures. Those who oppose it prefer to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals.

In one of the communities, an Indigenous man approached our team and asked, “Can they let the Colombians enter our lands without telling us anything?”

Another source expressed concern about the university’s irregular situation: “The chiefs were already saying that their children would be doctors; many mothers and fathers also believe in the project, dreaming of a better life for their children. But they [the university] had nothing, they started giving classes without any criteria,” said another person who did not want to be identified.

The chiefs were already saying that their children would be doctors; many mothers and fathers also believe in the project, dreaming of a better life for their children. But they [the university] had nothing, they started giving classes without any criteria

Person who did not want to be identified

Colombian excluded from the project says there was an ‘agreement’

In 2021, José Antonio Pérez Manrique arrived in the Jutaí region presenting the Indigenous university project. He introduced himself as a volunteer adviser to Indigenous people and general coordinator of an organization called the International Environmental Indigenous Guard of the Amazon, which, according to him, manages Indigenous universities in Brazil, Colombia and Peru and gathers the Tikuna people.

In Benjamin Constant, also on the triple border, there is a movement to create the Distinguished Indigenous University of Amazonas Peoples, which Manrique points out as one of his organization’s projects. However, Chief Eli Tikuna, who heads the project, said that Manrique had no current relationship with the university but confirmed that he had been in the region and that the “experience was not good.”

“He’s been here in our region and worked with us, but I don’t particularly recommend him. He had this idea of a carbon project to fund the university, but we stopped working with him,” he said, without providing further details.

Manrique told InfoAmazonia that the model of education funded by carbon credits would allow Indigenous people to implement their life plans. The proposal includes construction of what he called “ecovillages” and a series of promises to improve the lives of communities. And it must include a carbon project.

“We provide advice for communities to create their life plans based on our philosophy of forest protection, conservation, restoration and defense. Within the life plan, we created the university, and the entire project is funded by carbon credits,” he stated. Manrique himself gave lessons at the Indigenous university in 2022.

Pérez Manrique said he traveled with the Indigenous people of Jutaí to Colombia’s capital, Bogotá, where he introduced businesspeople linked to CommunityRedd+. When asked about the need for authorization by FUNAI or the Brazilian government to develop the projects, he disagreed and said that the chiefs “are the authorities” to approve these projects: “There is no problem with that, because the Indigenous people can do it.”

According to Manrique, the carbon project in Solimões is now advanced and should generate carbon credits soon. However, he said he was excluded from the process by Concepto Carbono and accused the businessmen of betrayal.

“They didn’t allow me to supervise and inspect the project, which was our agreement. If they don’t want to do the right things, I’ll talk to the chiefs and we’ll replace the companies,” he sustained, saying he would report the others.

“They cut the money for the university project. Students need to attend school, and the classes didn’t happen this year but will be resumed next year. We’ll report them to the police if we have to. They are bribing the Indigenous people,” he said, without providing evidence.

Asked to comment on the matter, the newly created Ministry of Indigenous Peoples said it was gathering information from all carbon projects on Indigenous lands for an in-depth assessment by its legal team. The ministry also stated that lack of regulation on the subject hampered the work of Indigenous agencies, which are often not correctly informed about the implementation of these projects.

* Andrés Bermúdez Liévano (CLIP) contributed to this story

This report is part of the series “Money that grows on trees: financialization of the forest puts pressure on Indigenous Lands,” produced with support from Journalismfund Europe, in partnership with Mongabay.