In Venezuela’s southern Amazon region, Pemón Indigenous communities are caught between encroaching armed groups and illegal gold miners.

6 August 2023

By María Ramírez Cabello

It’s Friday night, and in the center of Ikabarú, a community in the Pemón Indigenous territory in the southern Venezuelan Amazon, the preaching of a couple of Christian pastors brings back bad memories to local residents. The scene, the hustle and bustle, and the singsong voices are similar to those of the days before the so-called Ikabarú massacre, an armed operation three years ago in which eight people were killed.

The event — on the night of Friday, Nov. 22, 2019 — signaled the importance of the Indigenous territory for criminals involved in illegal gold mining in this vast area of southern Venezuela and neighboring countries.

A cocktail of armed groups — guerrillas, illegal gold miners and criminal gangs known as syndicates or “systems” — shares control of mining deposits in southern Venezuela, in the states of Amazonas, Bolivar and Delta Amacuro. They finance their operations with income from extortion and the trafficking of minerals, drugs and weapons, and operate with virtually no resistance from the government in the biodiverse and sparsely populated region.

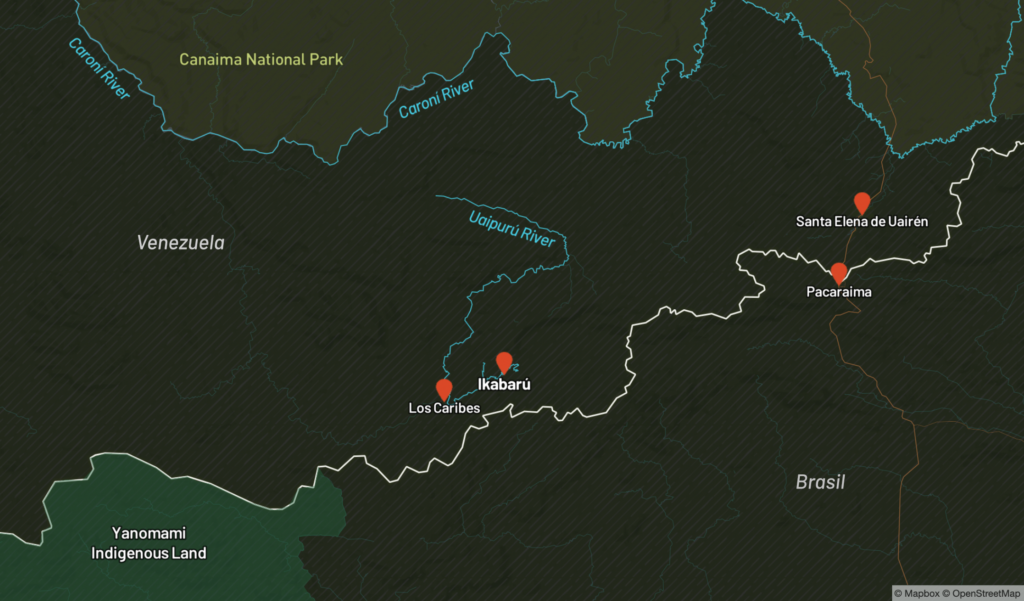

Ikabarú is in a jungle area practically surrounded by armed groups operating in the north and east of the Venezuelan Amazon and by illegal gold miners, known as garimpeiros, who operate to the west in Brazil. Much is at risk. Besides being part of the Amazon, this area of the Venezuelan jungle feeds the Caroní River, Venezuela’s second most important river and the country’s main source of electricity.

Not by chance does this resource-rich and lawless mining area straddle two environmentally protected areas, one of which is a strategically important water source.

In the village, there is no need to ask what happened the day of the Ikabarú massacre. The story emerges spontaneously, usually as an explanation for the slow pace of the days here, which pass in silence, with few visitors and with the nostalgic air of those who have lost something valuable.

“There were people who left. There was trauma. Now they are returning,” one resident says, standing just a few meters from the place where the shooting began.

That night, at around 7 p.m., a dozen armed men, hooded and dressed in black, shot at a group of people in front of a commercial establishment, shouting, “Your leadership is over, Cristóbal. This is El Ciego’s gang!”

Cristóbal Ruiz Barrios, whose body appeared several days later not far from Ikabarú, was a miner in a deposit known as La Caraota, and those who were looking for him intended to replace him, as has happened with other mining claims in southern Venezuela’s rich gold and diamond deposits.

El Ciego (Spanish for “the blind man”), the alleged mastermind of the plan, heads one of at least seven active criminal groups that control mining areas in the Venezuelan jungle, where they have operated with the tacit knowledge of state forces for more than a decade.

But because of the peculiarity of the event, local leaders — Indigenous and non-Indigenous — attributed the massacre to state security forces. The objective, they say, was to justify further militarization of the Pemón territory and absolute control of the mineral wealth.

That same year, a Venezuelan Army convoy on its way to the Brazilian border fired on the Kumarakapay Indigenous community, killing three Pemón and leaving dozens wounded, a clash that led to a military advance amid a decade of retreats in the struggle for control among guerrillas, garimpeiros and even military forces that share the territory.

“It’s part of the government’s strategy, which reached its peak in 2019. They sponsor these armed groups and create a situation to justify militarization,” says one Indigenous leader, who requested anonymity for security reasons. Abuses by the military and the invasion of Indigenous territories by armed groups intensified around a decade ago, she adds.

Amid this upheaval, Ikabarú seems like an island, one of the last places that has not been taken over. Although the days there appear to pass tranquilly, the threat of incursion by criminal groups and new actors seeking a share of the gold and diamond wealth remains latent.

“They are entering the communities little by little, like a peaceful invasion,” people in Ikabarú warn.

Although there is no active armed organization as there is in the country’s other mining districts, the area is coveted by the so-called “syndicates” or “systems” that operate in neighboring municipalities. It is also eyed by garimpeiros just 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) south, in Brazil, where they invaded the ancestral lands of the Yanomami people with support from criminal groups.

A third group — which is not new, but which has gained renewed strength — may also have its sights set on the region: Guyanese miners, who operate huge platforms where they scoop up riverbeds in the upper basin of the Caroní River.

Since the mid-2000s, state and non-state armed groups have been violently competing for control of mining areas in southern Venezuela. The greatest pressure has been concentrated in Bolívar, the largest state in the Venezuelan Amazon, where the U.N. Human Rights Council has documented massacres, disappearances and human rights violations.

Violence and mining expansion have peaked in the years of lowest oil production, the main source of income for this nation, which has the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves. In 2016, the government of President Nicolás Maduro created the Orinoco Mining Arc, saying it would “reorganize” mining in the south. Instead, however, illegal mining has expanded rapidly in the area, facilitated by armed groups that wield criminal authority.

GOLD AND DIAMONDS A MAGNET FOR MINERS

Ikabarú is at the end of a nearly impassable dirt road that resembles a rocky, dried-up river bed. It is in the Pemón Indigenous territory in the municipality of Gran Sabana, in the southern state of Bolívar, about eight hours from Santa Elena de Uairén, the largest town in the area, and 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) from the Brazilian border.

Along the roadside, a visitor approaching Ikabarú sees Indigenous people with metal detectors waiting for the sound that will alert them to the presence of precious metal. Renting the equipment, for a tenth of a gram of gold per day, is one of the new businesses. The prospectors search among innumerable mounds of earth extracted from old mining claims, mainly in the 1990s, when the government granted mining concessions. It is literally a mine field, where the once-crystalline waters of streams like the Chaveru are now muddy with sediment churned up by miners.

Mining is clearly the central livelihood here. In town, where the population is mainly non-Indigenous, signs advertising sweets and bread are mixed with others offering to purchase gold and diamonds, and still others hawking gasoline, diesel fuel and electric generators. In the daytime, there is no electricity and the town falls into silence. Countless houses seem abandoned or have been put up for sale. Of 10 restaurants active before the massacre, only one remains.

But Ikabarú has not been taken.

“Between July 2016 and March 2017, more than 8,000 miners entered Ikabarú, some of them even on foot,” recalls Lisa Henrito, captain, or leader, of the Maurak Indigenous community. The situation at the Kimiyo mine in Hachaken forced the Indigenous territorial guard to evict 648 of those miners.

“In that group, we detected seven subjects linked to ‘El Ciego’ of La Paragua. That group was already raising its head. They even tried to kidnap two territorial guards,” she says. It was an attempt to seize that island in the state of Bolívar.

Ikabarú is in a region rich in minerals

Indigenous Pemón communities are caught between armed groups seeking control and Brazilian and Guyanese miners entering their territory

“The intention behind that massacre was to take over the mines and bring in their people, but we know where these intentions come from — from the government itself. Those are blatant actions,” says Juan Gabriel González.

González is general captain of Sector VII of the Pemón people, one of eight geographical areas into which the Indigenous communities of Venezuela’s Gran Sabana are organized. Each community and each sector has a leader, called a captain,

Six months after the massacre, in 2020, members of the criminal group contacted him. One said he was El Ciego and he wanted to talk to González.

“They started writing to us that they wanted to send people in to control the mines, but we rejected that in a statement issued with the communal councils,” the Pemón leader says. “We will not accept those people.”

When miners began flooding into Ikabarú, the indigenous leadership, or captaincy, took stronger measures to control access. Even now, anyone wanting to enter the area must request authorization from the general captaincy in Santa Elena de Uairén. Travelers going to Ikabarú generally must show the permit at three checkpoints set up by the Indigenous territorial guard, an internal security structure created in 2001 to resolve domestic problems in the community, but which over time became a form of self-defense against invasion by outsiders. The Pemón people who participate wear black and act as sentries, but do not carry firearms.

That control, however, has not stopped the threats and the influx of miners. In a September 2022 report, the U.N. Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela noted that “given their strategic position and gold wealth, the indigenous territories in Gran Sabana and other neighboring municipalities have been a focus of interest for both the State and armed criminal groups. The indigenous population in these areas has resisted these interests, which has led to conflicts and violent clashes.”

BRAZILIAN MINERS CROSS THE BORDER

Venezuelans are not the only ones who covet the Pemón territory. Brazil and Venezuela share a 2,199-kilometer (1,366-mile) border. At the border crossing that connects the Venezuelan town of Santa Elena de Uairén with the Brazilian town of Pacaraima, tens of thousands of Venezuelan migrants have passed through tents set up by the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR). But informal crossings elsewhere in the jungle may see a flow in the opposite direction.

“Ikabarú can be reached by land, by air and by trails from Brazil,” says Luis Rodríguez, a 33-year-old Venezuelan miner who came to try his luck along the banks of the Ikabarú River less than a year ago, attracted by the reputed purity of the gold in these deposits.

The presence of Brazilians on Venezuelan soil is not unusual — they have been mining here for decades.

“The Brazilians taught the Venezuelan Indigenous people how to drill,” said one local resident, referring to the prospecting technique for analyzing soil and locating mineral deposits.

But Brazilian President Lula da Silva’s pledge to put an end to illegal mining in Yanomami territory in that country could lead more Brazilian miners to cross the border, posing a threat to Indigenous peoples in Bolívar and across the Venezuelan Amazon. This region has seen the greatest violence associated with illegal mining, including the Haximu massacre in 1993, in which 16 Yanomami people were brutally murdered by Brazilian miners.

On the banks of the Ikabarú and Uaiparú rivers, earth-moving equipment rumbles as it fractures the Earth’s crust to create open-pit mines. These powerful pieces of equipment are owned by Brazilians. These points are more than a two-hour drive from Ikabarú over a rocky road that makes access nearly impossible. The road leads to the river port of Los Caribes. From there, the illegal deposits can be reached by motorboat.

González, the Pemón leader, confirms that Brazilians have been working in the area for more than 30 years under the rules of the Indigenous captaincy. But with the military eviction from Brazil, they have begun to enter Ikabarú. Miners isay the routes they use include old trails in Sierra Beleza or La Leoncia.

“They have wanted to enter Ikabarú, but we are rejecting them,” González says. “They have been displaced and evicted, but we do not allow them to enter our territory.”

According to González, the garimpeiros have tried to gain entry by offering to finance mining equipment for residents. “We already know what mechanisms they want to use to enter the area. We have closed the permits to enter,” he says, adding, “We’re mounting surveillance. We are alert.”

‘MISILES’ ON THE IKABARÚ RIVER

As garimpeiros increasingly set their sights on this region of Venezuela, one concrete sign of their interest is the arrival of huge rafts carrying dredging equipment, a phenomenon imported from Brazil.

A trip along the Ikabarú River reveals only a couple of active open-pit mines and more than a dozen abandoned deposits. In satellite images, these mining camps appear to be active. But people familiar with the area say that those operations, where diamond-washing machinery still sits on the river bank, were paralyzed during Plan Caura, a 2010 military operation aimed at eradicating illegal mining.

Nevertheless, in the meandering river, bordered by thick forests, where macaws fly across the sky, the turbidity of the water is not an encouraging sign.

On the river bank, a couple of men assemble huge, green metal pieces that arrived a few days earlier, transported in five trucks along the dirt road that leads to Ikabarú and the port of Los Caribes. The passing of the convoy one morning in mid-February did not go unnoticed. It’s not unusual to see heavy vehicles loaded with food and gasoline, but the huge platforms were the talk of the town. And they’re not the only ones. Beyond the docks, three other giant rafts operate continuously.

Known as “misiles,” these enormous dredges work illegally day and night. They are so wide that besides holding heavy equipment that stirs up sediment on the riverbed and sucks it through pipes that connect to a large sieve, where the gold and diamonds are washed, they also have space for three to five operators to move around easily and have a rest area.

The first “misil” beyond the platform under construction is operated by a group of Guyanese miners whose camp is just a few kilometers away.

“The captaincy has full knowledge of these Guyanese and Brazilian dredges. They are the ones with the biggest equipment,” says a Pemón resident of the community of Playa Blanca, who asked to remain anonymous.

Thin, amber-colored tributaries of the Ikabarú join the thick, swirling river, highlighting the ecological damage to the waterway, whose banks are home to at least a dozen Indigenous communities. On shore and in ponds, toxic mercury is used to amalgamate the gold, extracting the particles from sand and sediment. The highly volatile heavy metal then returns to the air, soil or water. In the water, it is transformed into methyl mercury and accumulates in fish tissue, an effect that magnifies as it goes up the food chain.

“We know this is illegal and that we are damaging the environment,” says a member of a communal council that is being created in the port of Los Caribes, the supply point for food and other items used in the mines and on the rafts. This non-Indigenous organization, protected by the Law of Communal Councils, is another factor in conflict in the territory. The Indigenous captaincy maintains that the organization wants to impose its own interpretation of the law that created communal councils as participatory bodies for facilitating the implementation and oversight of public policies and community development projects.

They agree on one thing, though. Like the Indigenous people, the member of the communal council justifies the rafts’ presence, saying their environmental impact is minimal. He and his team, he says, control security and access to the mines. In the absence of the state, they have taken the law into their own hands, drawing up improvised “expulsion notices” for anyone who enters the mines to “misbehave” by committing abuses or causing violence.

Both land and river miners extract gold and diamonds. According to a 2021 study in a journal of the Ministry of Science and Technology, Ikabarú is the territory in the state of Bolívar with the greatest potential for diamond production. The authors write that most of the diamonds in Ikabarú are of high value because they are eight-sided crystals with cut percentages — a reference to the number of the facets, which give the diamond its brilliance — greater than 60%.

Miners in Ikabarú talk little about diamond mining, but in the port of Los Caribes, one 31-year-old miner waiting for a boat to transport him to the nearest mine takes a small plastic container out of his pocket and empties tiny, perfectly shaped diamonds into his hand.

Between 2004 and 2010, Venezuela registered an average annual production of about 18,000 carats of the gem under the Kimberley Process, a voluntary agreement in which 82 countries set minimum standards for the supply of conflict-free diamonds. Venezuela pulled out of the agreement in 2008 because it was impossible to monitor the origin of the stones, but returned to the process in 2016.

In 2020, Venezuela reported production of 794 carats on the international certification system portal, but informality has gained ground, mining is illegal and much of the production is not reflected in official statistics. As part of the common agreement, participating countries commit to implementing internal controls and publishing the figures of their annual diamond trade, as well as to transparency in production and trade data. Venezuela has filed no reports for 2021 or 2022.

Official recognition of the Pemón people’s territory has not prevented incursions by armed outsiders. In 2016, Indigenous leaders set up two checkpoints on the road to Ikabarú to control access. In 2017, the Indigenous rights organization Kapé Kapé reported that a group of 70 armed people “of various nationalities” had kidnapped the inhabitants of Hachaken, another Pemón community, for four days. According to the report, they intended to take control of gold mining there — the same motive that was behind the 2019 Ikabarú massacre

But although mining is illegal, the state-run Venezuelan Mining Corporation (CVM) reached an agreement with some Indigenous communities to supply materials. A 230-liter (60.7-gallon) can of fuel sold by CVM, for example, costs 6.5 grams of gold.

The fragility of the situation is evident. Even at the expense of their territory, the Pemón people in this corner of the jungle have proposed legalizing mining so they can consign gold to the Maduro government in a country fragmented by the actions of criminal groups. They want to open the door to legal mining.

“We no longer want to hide or pay extortion fees, but pay what is due,” says González, the captain general. For now, the potential hazards that would be exacerbated by increased mining do not seem to worry him much.

“This is our territory,” he says, “and we are going to keep it.”

Amazon Underworld is a joint investigation of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Armando.Info (Venezuela) and La Liga Contra el Silencio (Colombia). The work is carried out in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and financed by the Open Society Foundation, the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN NL).