3 August 2023

By Bram Ebus and Rodrigo Pedroso

It’s a late afternoon in February, and three young men lounge on the deck of an old boat with peeling white paint moored along Brazil’s Puruê River, deep in the Amazon near the southernmost tip of Colombia. Tied to the boat is a battered, barn-like structure housing a tangle of chutes and gears and mounted on a barge. This is a mining dredge, one of scores along this narrow, winding river. Illegal and destructive, they churn up the riverbed, producing tens of millions of dollars’ worth of gold every month. This one is idle, though, awaiting repairs.

Reporters from Amazon Underworld are talking with the miners on the dredge just before sunset, when the silence is broken by the sound of a powerful outboard motor. A smaller boat pulls up, with a uniformed man wearing a balaclava and wielding a Brazilian-made assault rifle standing on the prow. He and five companions leap aboard the miners’ boat. Identifying themselves as a Brazilian Military Police river patrol, they pat down the miners, order them to fix a meal and settle in for the night.

As the police officers wolf down canned meatballs with tomato sauce and dried cassava meal, the owner of the mining dredge arrives, a man known as Cabeludo, a nickname taken from the gray hair he ties back in a ponytail. The boat and dredge are both the miner’s business and the home he shares with his wife, months-old baby, a cook and eight workers.

He seems to take the uniformed intruders in stride, even when one pulls out a mobile phone and passes around a photo that is circulating in a WhatsApp group. It’s a corpse. Just hours earlier, he says, the owner of a mining dredge was murdered, allegedly by one of his workers, who fled into the jungle.

“He took half a kilo of gold with him,” one of the officers says.

In Brazil’s Amazonas state, near the border with Colombia, illegal mining is fueled by rising gold prices and surrounded by violence and corruption.

Video: Google Earth

Dangerous and lawless,

this area has become a magnet for fortune seekers, modern-day pirates, rogue law-enforcement officers & Colombian guerrillas.

Video: Andres Cardona

Some illegal miners, known as garimpeiros, worked on smaller dredges in the area as early as the 1980s.

But hundreds of industrial-size mining barges arrived in the municipality of Japurá, in the state of Amazonas, after former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro took office in 2019 with a pledge to legalize informal gold mining.

Photo: Andrés Cardona

Besides scooping up so much sediment that they change the course of the river, the miners dump hundreds of kilograms of mercury into the environment.

The dredges also encroach on protected areas, including one inhabited by a nomadic Indigenous tribe that shuns contact with outsiders.

Photo: Andrés Cardona

Both Brazil’s and Colombia’s new presidents, Lula da Silva and Gustavo Petro, have pledged

to rein in the illegal mining that churns out hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of gold, financing armed groups on both sides of the border.

Photo: Alex Rufino

Nevertheless, the illegal gold mining that has swept through the Amazon, combined with drug trafficking,

has created an underground economy worth billions of dollars, far outstripping government budgets to combat them.

Photo: Alex Rufino

EXTORTION, CORRUPTION AND VIOLENCE

Before the 1990s, most of the illegal gold mining in this region, where Colombia’s Puré River becomes Brazil’s Puruê and flows into the Japurá, was done by small-scale prospectors. But with the rise in gold prices in the early 2000s, organized crime groups cashed in on the lucrative industry, including Colombian guerrillas who saw illegal gold mining as a way to launder profits from the drug trade.

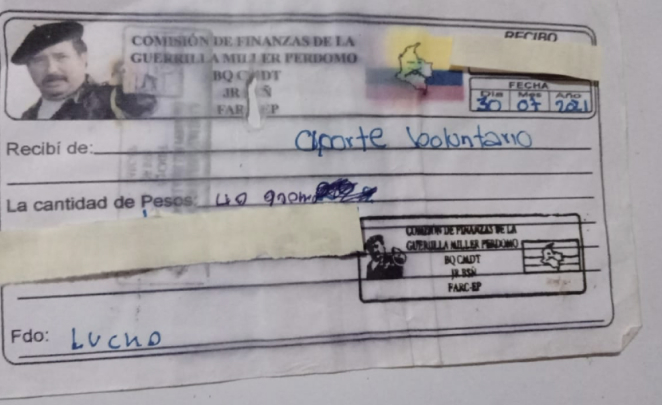

After a 2016 peace deal between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a dissident guerrilla group began building a new criminal enterprise, financing their ongoing armed violence in part by shaking down illegal miners for what they called “voluntary contributions.”

Some time back, the Brazilian Army faced off with guerrillas on the Puruê River, recalls Getúlio,* a miner from São Paulo who operates an industrial-scale dredge — called a draga in Portuguese and Spanish — about six times the size of Cabeludo’s.

An industrial-scale dredge on the Puruê River can cost

OVER US$500,000

and produce as much as

3 KILOS OF GOLD A MONTH.

As Getúlio sips a fresh cup of coffee, thousands of gallons of muddy water clatter down a metal chute behind him. The miner owns two colossal dragas, which can produce kilos of gold a month, dwarfing the tens of grams produced by smaller dredges like Cabeludo’s, which are known as balsas. He knows that makes him a target.

“The guerrillas came to this river, collecting taxes from miners,” Gétulio says, digging out a receipt that says he made a “voluntary contribution” of 40 grams of gold.

At first, the guerrillas collected 20 grams of gold a month, but soon they began to demand 20 grams a week.

“They used threats and intimidation to collect the tax. The garimpeiros warned the guerrillas that the army was coming to clear them out,” the miner says.

In 2021, the Brazilian Army responded by sweeping the guerrillas from most of the Puruê River. “There was a confrontation here,” Getúlio says. “The Brazilian Army and Navy stayed here on the Puruê River for three months.”

Brazilian authorities have been tight-lipped about the operation. In an official statement, the Federal Police gave no details except to say that nine people were arrested, including “two dissidents from a foreign guerrilla group,” and authorities seized a kilo of gold, cash, weapons, ammunition, mercury and cocaine base.

In April 2023, a clash between FARC dissidents and unknown armed persons resulted in the deaths of several guerrillas, indicating that the armed group was still present despite attempts to eliminate Colombian guerrillas from the area in 2021. The shootout took place in a border region, although it remains unclear whether it occurred on the Brazilian or Colombian side. Throughout this period, the guerrillas continued to target Brazilian miners for extortion. Notably, however, a different armed group — this time belonging to the state — began benefiting from the illicit operations on the Brazilian side.

In February, when Amazon Underworld visited the Puruê River, miners claimed they paid Military Police officers 30 grams of gold per dredge monthly for protection, and another amount up to 50 grams to the prefect in Japurá. Getúlio said the payments were part of a deal in which the miners paid for a boat and fuel for police to patrol the river and the mining area. “I help the security forces so they will also help me,” he said.

In an emailed response to questions about the accusations, Japurá’s municipal secretary of administration and coordination, Renilton Dos Santos Solarth, called them “fanciful rumors lacking in veracity.” He said the municipality has received no reports of public servants illegally receiving gold.

The Military Police responded to an inquiry by stating that police have conducted operations to investigate piracy, resulting in the arrest of several offenders, including Military Police personnel. They did not respond to questions about claims that Military Police officials extorted payments in gold from illegal miners.

Miners report paying protection money to Brazil’s Military Police

For days at a time, miners say, police patrol the Puruê River in boats with powerful outboard motors, stopping at dredges and collecting their gold. According to miners:

Military Police function as vigilantes protecting illegal miners from thieves and Colombian guerrillas.

Military Police collect a monthly 30 grams of gold per mining dredge.

Military Police traffic gold through Japurá.

The municipality of Japurá also collects gold payments, up to 50 grams a month per mining dredge.

In an emailed response to an inquiry, a municipal official denied the accusations. Military Police said an investigation of accusations of piracy resulted in several arrests, including Military Police personnel, but did not respond to questions about alleged extortion of miners.

Besides guerrillas and corrupt police, another threat are the bands of heavily armed pirates who roam the rivers, especially targeting miners, as well as the occasional boat carrying cocaine and marijuana from Colombia. Getúlio says he once lost 130 grams of gold and his wife’s jewelry to seven armed pirates on the Japurá River. “They shot at us from a distance, but missed,” he says. “They overtook us, overpowered us and demanded the gold.”

Miners and local boat pilots claim some of the pirates are police officers — “more pirate than the pirates,” one experienced boatman in the Japurá municipality says. In July 2022, five Military Police officers were detained and suspended for the crime of piracy. The Justice and Discipline Office of the Military Police of Amazonas State opened an investigation into the case nine months later, after Amazon Underworld inquired about it.

ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE ‘IRREVERSIBLE’

On both sides of the Colombian-Brazilian border where the Puré River becomes the Puruê, areas set aside to protect forests — and people living in them — are threatened by illegal mining on the river. On the Brazil side, the Puruê River falls under the jurisdiction of the Amazonas state government and the Brazilian Army, while the Juami River, a nearby mining hotspot, is inside the Juami-Japurá Ecological Station, a protected area managed by the federal government.

Besides the dredges that operate with impunity along the rivers, in some places miners with heavy equipment are pushing their way into the forest, threatening to turn the tropical landscape into a moonscape devoid of vegetation and pocked with water-filled craters. Calculations by the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team, which has an office in Brasília, indicate that about 1,010 hectares of forest have been destroyed by illegal mining along the Puruê River. More than half of that deforestation occurred in 2022.

“There has been a general abandonment of the region in recent years, which has facilitated the entrance of all kinds of criminals, such as river pirates, drug dealers, and gold miners,” says Joel Araujo, who heads the government environmental agency IBAMA in the state of Amazonas. “Violence has increased and criminal groups have taken the place of the state, co-opting young people and entire communities along the rivers.”

During the Bolsonaro administration, the country’s main environmental agencies were headed by police officials who dismantled infrastructure and closed checkpoints, including one near the Juami-Japurá Ecological Station. It was still closed in June, six months after Bolsonaro left office, but government officials said they planned to reopen it.

On the Colombian side of the border, the government lost control over the Puré River after FARC dissidents ordered park rangers to abandon Puré National Park in 2020. “Because of the threats posed by the existence of the FARC, park rangers are unable to protect the park,” the protected area’s director, Eliana Martínez Rueda says, adding that the guerrillas issued new threats and restrictions in January 2023.

Puré National Park was created in part to protect the Yuri-Passé, a semi-nomadic Indigenous group that shuns contact with outsiders. But with the rangers gone, dredges began to encroach on the area, and illegal mining continues there. The Colombian Navy, Army and Police did not respond to requests for information.

Drug traffickers use the park’s rivers and there are clandestine airstrips in the area, Martínez says. Illegal miners also cross the border from Brazil into the park. “It’s already a no man’s land,” she adds, “and they enter Colombia easily.”

She worries that the Yurí-Passé, a small tribe, could be wiped out by violence or disease if contacted by armed groups or illegal miners. “It’s a health risk, because [outsiders] can bring diseases for which [the Yuri-Passé] have not developed immunity,” she says.

“Governments don’t have control or authority, so lots of these remote areas have allowed illegal mining groups and other illegal mafias to flourish, especially in transboundary regions,” says Brian Hettler, a geographer and cartographer with the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team, who has been mapping illegal mining dredges. “The environmental damage being done by illegal mining is largely irreversible,” he adds.

The sediment churned up by miners alters the course of the rivers, and mercury used by the miners accumulates in the tissues of fish and the animals that feed on them, including humans. Some Amazonian fish travel long distances, so fish with high levels of mercury, which causes digestive and neurological problems, can affect people far from mining areas, including isolated groups like the Yuri-Passé.

A 2018 study of hair samples from Indigenous people in the Colombian Amazon near the Brazilian border found that about 90% of the community members had levels of mercury exceeding the maximum threshold recommended by the World Health Organization, in some cases by as much as four times.

HIGH RISKS AND BIG PROFITS

Estimates of gold production for an industrial-scale dredge on Brazil’s Puruê River vary widely, but conservative calculations range from about 2.5 to 3 kilograms (5.5 to 6.6 pounds) a month. To enter the legal economy, illegal gold is funneled through a complex network of transporters, intermediaries, gold shops and traders.

On the dragas, dredge owners melt their gold into bars. They, their employees and others in the gold mining areas, including sex workers, who are also paid in gold, travel periodically to the towns of Japurá and Tefé to turn the precious metal into cash. In a region that has no highways, travel is by passenger boat — a constant target for pirates.

Where does it go? The gold-trafficking route

Gold dredged from the Juami y Puruê rivers is exported through Manaus to international markets

Gold trafficking route by plane

Gold trafficking route by boat

Secondary route by boat

A Military Police officer who asked to remain anonymous claims to escort shipments of illegally mined gold on private flights from Japurá to Amazonian cities such as Porto Velho, Boa Vista and Manaus, where buyers receive the precious metal without inquiring about its origin.

“The transport is simple. Every day, flights depart from Japurá and we safely transport the draga owner’s gold, which we call ‘big gold,’ to the capital where we can get the best price for it,” he says. Japurá’s airport has permission from Brazil’s National Civil Aviation Agency to handle only private flights. Smugglers face a higher risk of detection when they land at larger airports where government inspectors are stationed.

The Military Police officer, who is from a large and economically poor family in the state of Amazonas, sees gold mining as a solution to poverty in the region. “It’s illegal, but not immoral,” he says. “It should be legalized, because now [miners] don’t pay taxes and the money doesn’t stay with the people of Amazonas. It ends up going abroad.”

AT US$54 A GRAM,

the price in Japurá, a smuggler or a dredge owner could be carrying the value of a middle-class apartment in Manaus in his pocket.

A man in a shop in Manaus displays a one-kilogram bar of gold | Rodrigo Pedroso

Before the gold leaves the Amazon, it usually is melted and molded into rectangular bars that weigh one kilogram (2.2 pounds) each and can fit in an adult’s hand. At US$54 a gram, the price in Japurá, a dredge owner or smuggler could be carrying the value of a middle-class apartment in Manaus in his pocket.

Even if law enforcement operations destroy a dredge, the activity can still be profitable. According to miners, it costs about US$500,000 to US$600,000 to build a large draga in the Japurá region — a sum the owner of a highly productive dredge can recoup in a few months.

For those involved, the potential payoff is worth the risk, and the huge amounts of money involved underscore the difficulty of reining in the illegal mining that has extended throughout the Amazon.

ILLEGAL GOLD SOLD IN ‘GOOD FAITH’

Besides corrupt police and government officials, dredge owners and their representatives also transport and purchase gold from the Puruê and Juami rivers and resell it to independent gold dealers, mining cooperatives and securities dealers authorized by Brazil’s Central Bank and Securities and Exchange Commission.

Gold buyers are not required to verify the origin of the gold. They need only provide a “good faith” declaration that it was extracted from an area authorized by the National Mining Agency. The gold can then be sold. In May, Brazil’s Supreme Court suspended the “good faith” presumption and ordered the government to adopt a new set of rules within 90 days to control the gold trade.

The lack of regulation makes gold trading an attractive way for criminal groups to launder proceeds from drug trafficking and other illegal activities.

In 2022, as the result of a law enforcement investigation into illegal gold mining by dredges in the Amazon, 18 people were arrested and more than US$ 1 billion in assets of various trading companies were blocked.

The investigation, called Aerogold, found that the gold scheme in the Japurá region involved a chain of at least 100 people who received the gold and inserted it into the legal economy, so it could be sold or exported. They then used various businesses to launder the profits. A new phase of the Aerogold investigation is currently under way.

A CRACKDOWN AND AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

For years, career gold miners like Getúlio, who own dragas, have lived in different worlds, shuttling between the Amazon, large cities on the Brazilian coast and international destinations like Miami. “It’s the life of a garimpeiro,” he says. “It’s been 35 years, with a financial return that pays off for someone who knows how to enjoy his work and his money.”

In February, however, he was already eyeing an uncertain future ahead if the government followed through on the president’s pledge to dislodge miners from Amazonian rivers. “We’re already working this year, trying to make some money, because if that happens, we will stop being garimpeiros,” he said.

During the last week of May, Getúlio’s fears were realized when the federal environmental agency IBAMA, supported by security forces, led a crackdown and claimed to have destroyed 51 dredges on rivers in the municipality of Japurá, including the Puruê. Some videos circulating among miners show dredges engulfed in flames, while in others, dredge carcasses smolder as miners douse them with buckets of water.

Many more dredges, however, had been counted along the river during Amazon Underworld’s visit three months earlier. In addition, in satellite images from days before the crackdown, the water of the Puruê and Juami rivers is dark — the rivers’ natural color — rather than muddy with sediment churned up by dredges. That evidence, along with comments from miners at the time of the raid, indicates that miners had stopped operating before the government crackdown. Within a month, however, mining had resumed. The rivers were muddy again, and during overflights in early July, Amazon Underworld reporters counted 159 mining dredges on Brazil’s Puruê River and 9 on the Puré River in Colombia.

In early July, Brazilian media reported that an Army lieutenant colonel had allegedly leaked information about crackdowns to miners in the Japurá region, reportedly receiving nearly US$200,000 between 2020 and 2022 in exchange for warning them about planned law enforcement operations. The officer sometimes would delay these operations or alter the routes, as miners indicated they needed four days’ notice to conceal their dredges.

Flyover counts 159 dredges on the Puruê River

‘The only way to earn good money’

Illegal mining is a magnet for men and women from impoverished communities — some Indigenous, some not — in the Amazon, where education is poor and job options few. In the state of Amazonas, the average household earns less than the minimum wage, equivalent to about US$250 a month. The prospect of a brighter economic future leads workers to leave their families for months at a time to labor on a draga, where they’re paid in gold.

“I like having a car and motorcycle and enjoying a Heineken at a nice restaurant,” one miner said. “I worked hard for it — it’s not to show off. If you had the chance, you would, too. Don’t judge us. It’s the only way to earn good money here.”

Many of the huge industrial dredges are both home and workplace, with machinery filling the lower level and living quarters above that boast urban luxuries like television, high-speed internet and surveillance cameras. Living on dredges for months at a time, miners give the structures touches of home, keeping pets, tending small gardens of lettuce and scallions, and raising chickens for food. Cooks bake fresh bread and keep the miners supplied with jugs of sweetened coffee.

A pack of Coca-Cola costs one gram [of gold], a box of chicken is two grams. Everything is like that. A package of sausages is one gram. Everything is expensive, very expensive

Cabeludo

In February, several months before the government crackdown, the future appeared to be in doubt for subsistence miners such as Cabeludo, who shares the Puruê River with Getúlio. Despite the uncertainty, however, he was mainly engrossed in everyday tasks.

Cabeludo wants to give his child a better future and a different life. “I don’t want that for me or him,” he said in February. “I’ve suffered a lot here. People are tired, and hungry. My freezer is not freezing. I use rain and river water to shower.”

Life on the Puruê River is not cheap. Products come over large distances and river transport requires a lot of expensive fuel. And everything is priced in gold.

“A pack of Coca-Cola costs one gram, a box of chicken is two grams. Everything is like that. A package of sausages is one gram,” Cabeludo said. “You can find three beers for one gram, but sometimes it’s one for one. Everything is expensive, very expensive.”

Barefoot and bare-chested, he laughed as he wrestled his attention-seeking dog, Xangai, while hammering a piece of carpet to plug a crack on his balsa. Then he turned serious. Besides guerrillas and pirates, he also feared an impending raid by the Lula administration. Without a smartphone or internet access to keep up with miners’ WhatsApp chats, he worried that he might not find out until too late.

He hoped the government could help formalize his operation, instead of cracking down on it. “We’re hoping they’ll look out for the garimpeiros,” he said. “It would cost them nothing to legalize [the mining] so we could pay taxes. That would be easy. It would be a way to look out for us here, too, to take pity on the poor.”

The small balsa, with its dredging equipment, was all he had, he said, and if a raid happened, “That’s it for me. I won’t survive outside of mining. I really won’t.”

*Names have been changed

Amazon Underworld is a joint investigation of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Armando.Info (Venezuela) and La Liga Contra el Silencio (Colombia). The work is carried out in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and financed by the Open Society Foundation, the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN NL).